Section 7 Bovine Mastitis

- Alan Johnson

- Senior Research Officer, Limerick Regional Veterinary Laboratory, Knockalisheen, Limerick, Ireland

Dairy farmers are committed to producing food of the highest standard for consumers. Cellcheck, the National Mastitis Control Programme coordinated by Animal Health Ireland, in association with farmers, milk processors, service providers and Government, have been focusing on reducing somatic cell counts of milk produced in Ireland. Farmers are being encouraged to collect and submit milk samples from cows with cases of clinical and suspect subclinical mastitis for culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Bacteria are responsible for virtually all cases of mastitis; by identifying the agent responsible, important information about possible source of infection may be gathered, enabling a focus for control measures to improve milk quality.

7.1 Milk Culture in RVLs

All RVLs follow a similar procedure for culturing milk samples. Samples are initially tested for inhibitory substances, such as antibiotics, which can interfere with bacterial growth in the laboratory. At least four different types of agar plates are used to culture each milk sample. Using a sterile swab, a small quantity of milk is spread on to each plate (Figure 7.1). These plates are incubated at 37C for 24 hours. If, on inspection, no bacterial growth has occurred at that stage, plates are incubated for a further 24 hours. If there is no change after 48 hours of culture, the result no significant growth is entered.

Figure 7.1: Inoculation of agar plates for culture of a milk sample in Limerick RVL. Photo: Alan Johnson.

If bacterial growth is seen on plates, further tests are carried out to identify organisms growing (Figure 7.2). If milk sample has been contaminated, cultures usually yield a mixed bacterial growth (Figure 7.3); in these cases it can be difficult to identify the significant bacterial species and the result is entered as mixed bacterial growth. Contamination usually occurs when bacteria from sources other than milk inside the udder enter the sample. This could be from skin of the udder, sampler’s hands or from inside of the container itself, if the latter is not sterile.

For additonal information, see the Animal Health Ireland (2019a) webpage.

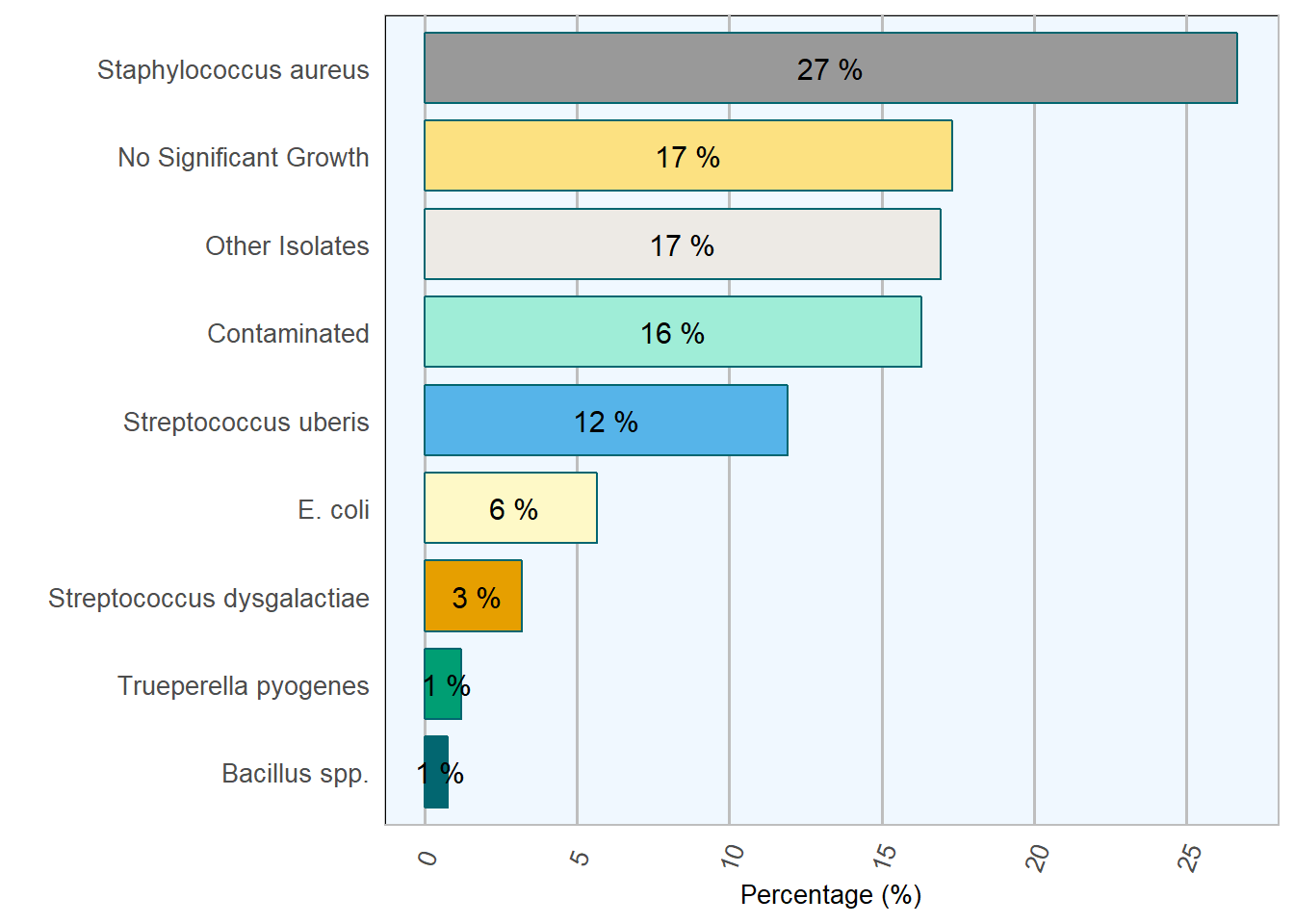

| Result | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 911 | 26.7 |

| No Significant Growth | 591 | 17.3 |

| Other Isolates | 578 | 16.9 |

| Contaminated | 557 | 16.3 |

| Streptococcus uberis | 407 | 11.9 |

| E. coli | 193 | 5.7 |

| Streptococcus dysgalactiae | 109 | 3.2 |

| Trueperella pyogenes | 41 | 1.2 |

| Bacillus spp. | 26 | 0.8 |

Figure 7.2: Staphylococcus aureus growing on a blood agar plate. Photo: Alan Johnson.

RVLs have seen an increase in the number of samples received for culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In 2018, 3413 individual milk samples were received for testing (Table 7.1)}.

7.1.1 Staphylococcus aureus

This organism continued to be the most commonly pathogen isolated in cases of mastitis by RVLs in 2018 (Figure 7.2). It was identified in 911, 26.69 per cent, of samples submitted (Table 7.1). Staph. aureus is the main cause of contagious mastitis and typically, though not always, spreads from cow-to-cow by contact with infected milk on cluster liners or on milker’s hands. It can be difficult to cure, particularly during lactation and culling is frequently the best option in older infected cows with persistently high somatic cell counts.

Other isolates, mostly coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp., were cultured from 578, 16.94 per cent, milk samples.

Figure 7.3: Mixed bacterial growth on a blood agar plate following culture of a contaminated milk sample. Photo: Alan Johnson.

Figure 7.4: Relative frequency of selected mastitis pathogens during 2018.

Staphylococcus aureus mastitis

Herds with mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus infection should reassess their milking hygiene. To prevent spread of infection, infected cows should be segregated and milked last or in a separate unit.

7.1.2 Streptococcus uberis

This organism is described as an environmental mastitis pathogen. It is usually due to faecal contamination of surfaces. Sub-optimal housing and poor udder hygiene can increase the risk of infection (Barrett et al. 2005). In addition, Strep. uberis also has some characteristics of a contagious pathogen and can be spread from cow-to-cow at milking time. Strep. uberis was isolated from 407, 11.92 per cent, of milk samples cultured during 2018 (Table 7.1).

7.1.3 Truperella pyogenes

This is the most commonly isolated pathogen in cases of summer mastitis. It is associated with a suppurative foul-smelling secretion and loss of the quarter for milk production. Insect vectors are considered central to its spread, hence its assotiation with the summer months.

A similar syndrome can be found during the indoor (in-house) season following a teat injury.

T. pyogenes was isolated from 41, 1.2 per cent, milk submissions.

7.2 Contaminated samples

In 2018 the number of samples described as contaminated was high at 557, 16.32 per cent. When collecting milk samples for culture, it is very important to collect them in a sterile manner. This will ensure that any bacteria isolated has originated from within the udder, and not from the teat skin, milker’s hands or non-sterile equipment. Contaminated samples usually result in growth of coliforms or a mixture of bacterial species

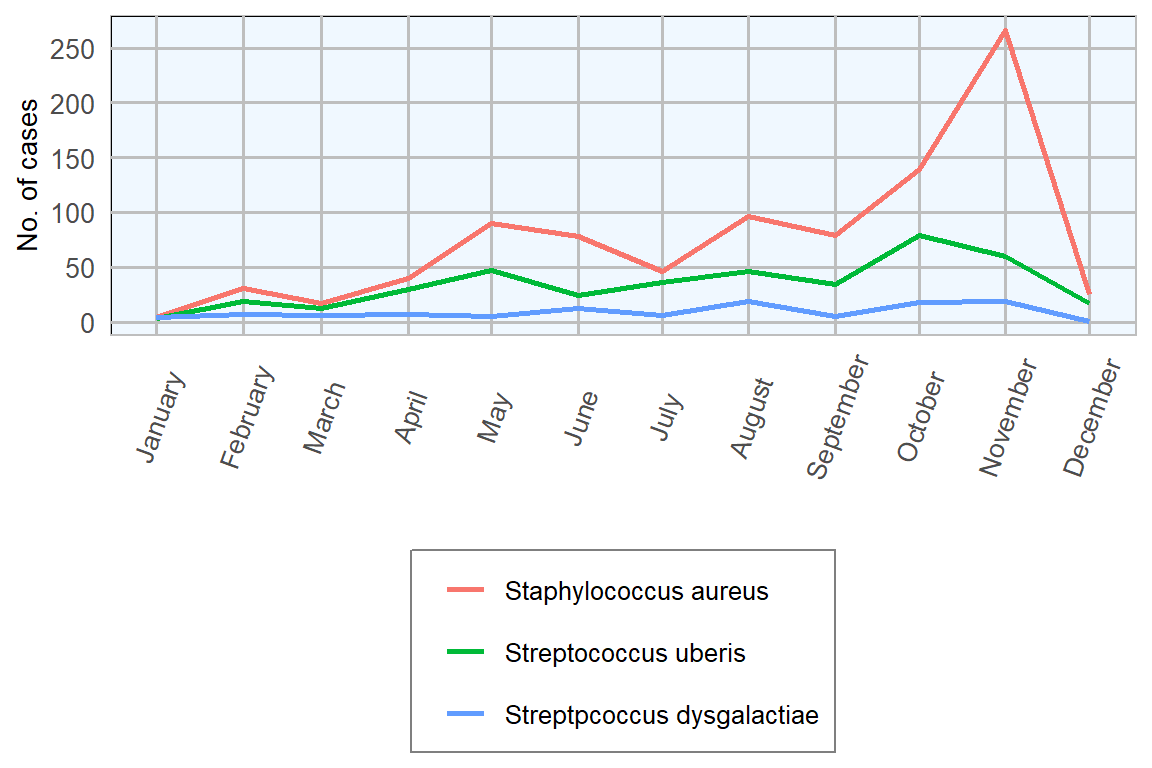

Figure 7.5: Monthly isolation counts of important mastitis pathogens from milk submissions in 2018 (n= 3413 ).

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5355 | 3469 | 2899 | 3329 | 2288 | 2315 | 2849 | 2416 |

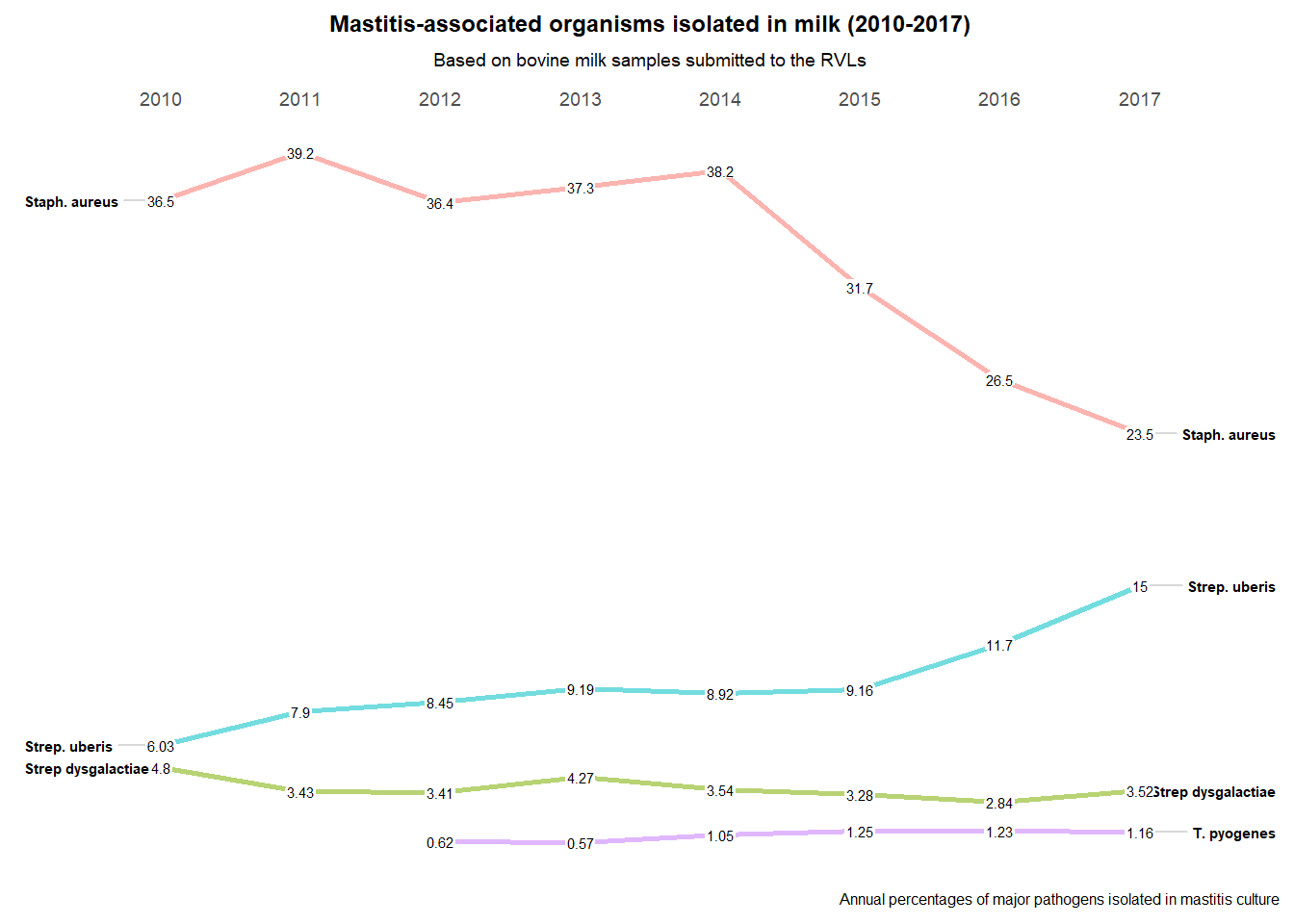

Figure 7.6: Mastitis-associated Organisms Isolated in Milk (2010-2017).

Milk Sample Collection for Bacteriology:

- Materials for Sampling

The quality of milk samples taken for laboratory examination is extremely important. An aseptic technique for sample collection is a necessity. Contaminated samples lead to misdiagnosis, confusion and frustration. If dry cow therapy decisions are to be based on the results of a small number of milk samples, it is vital that proper procedures are followed.

*Materials for sampling:

- Disposable latex gloves.

- Sterile screw-top plastic tubes ( capacity approximately).

- Cotton wool balls soaked in 70 % alcohol or medicated wipes.

- Paper towels. \end{itemize} \end{tcolorbox}

Over the last number of years there has been a fall in isolation rates for Staphylococcus aureus and a rise in isolation rates for Streptococcus uberis (Figure 7.6). This may be associated with increased attention by farmers to controlling the spread of infections from cow to cow at milking time.

Figure 7.7: Labeled milk sample bottle with date and quarter sampled. Photo: Alan Johnson.

However, results from 2018 show a reverse in this trend with a rise in isolation of Staph. aureus and a drop in Strep. uberis. Reasons for this are not clear but may be due to weather conditions during 2018; a cold winter and spring followed by a summer drought.

In many countries, Streptococcus uberis is the most commonly isolated mastitis pathogen.

\begin{widetext} \begin{tcolorbox}[colback=green!5,colframe=pinpblue,title=Milk Sample Collection for Bacteriology: ]

\begin{enumerate}[noitemsep]

- Take the sample before milking and before any treatment is given.

- Label the tubes prior to sampling with name/creamery number/herd number, cow number, quarter and date.

- Using a hand or paper towel brush any loose dirt, straw or hair from teat or underside of the udder. Washing should be avoided if possible. However, if teat is soiled it should be washed and carefully dried with paper towels.

- Put on gloves.

- Soak a number of cotton wool balls in alcohol.

- Clean teat thoroughly with alcohol soaked cotton wool or the medicated wipes until it is thoroughly clean.

- Remove cap from sampling tube. Place cap on a clean surface with closing side up. Hold open tube at an angle of 45 degrees (holding it straight up will allow dust etc. to fall inside). Using your other hand, discard first few streams of milk on to the ground before collecting three or four streams in the tube.

- Replace cap on sampling tube (Figure 7.7).

- If you feel that some contamination has occurred, discard sample and use a new tube.

- Place labelled tube in a fridge and cool to . This is very important.

- Sample should be taken to the laboratory as quickly as possible. If sample is handed to milk tank driver for delivery, ensure that it is placed in a cool box.

- If sample is not going to a laboratory immediately, it must be refrigerated until delivery.

References

Animal Health Ireland. 2019a. “Farm Guidelines for Mastitis Control.” Animal Health Ireland. http://animalhealthireland.ie/?page_id=52.

Barrett, Damien J., Anne M. Healy, Finola C. Leonard, and Michael L. Doherty. 2005. “Prevalence of Pathogens Causing Subclinical Mastitis in 15 Dairy Herds in the Republic of Ireland.” Irish Veterinary Journal 58 (6): 333. doi:10.1186/2046-0481-58-6-333.

A cooperative effort between the VLS and the SAT Section of the DAFM