Section 4 Bovine Neonatal Enteritis

- Denis Murphy

- Research Officer, Athlone Reginal Veterinary Laboratory, Coosan, Athlone, Co. Meath

Neonatal enteritis is consistently the most frequently diagnosed cause of mortality in calves less than one month old in the Republic of Ireland. It is generally caused by the interaction of one or more infectious enteric pathogens and several predisposing factors.

4.1 Neonatal enteritis

The most common clinical presentation in neonatal enteritis is watery diarrhoea (occasionally containing blood) usually leading to dehydration and, in severe cases, progressing to profound weakness and death. In order to identify the enteric pathogens involved in cases of neonatal calf diarrhoea, a series of tests are performed on faecal samples collected at post mortem from affected calf carcases or submitted by veterinary practitioners from clinical cases.

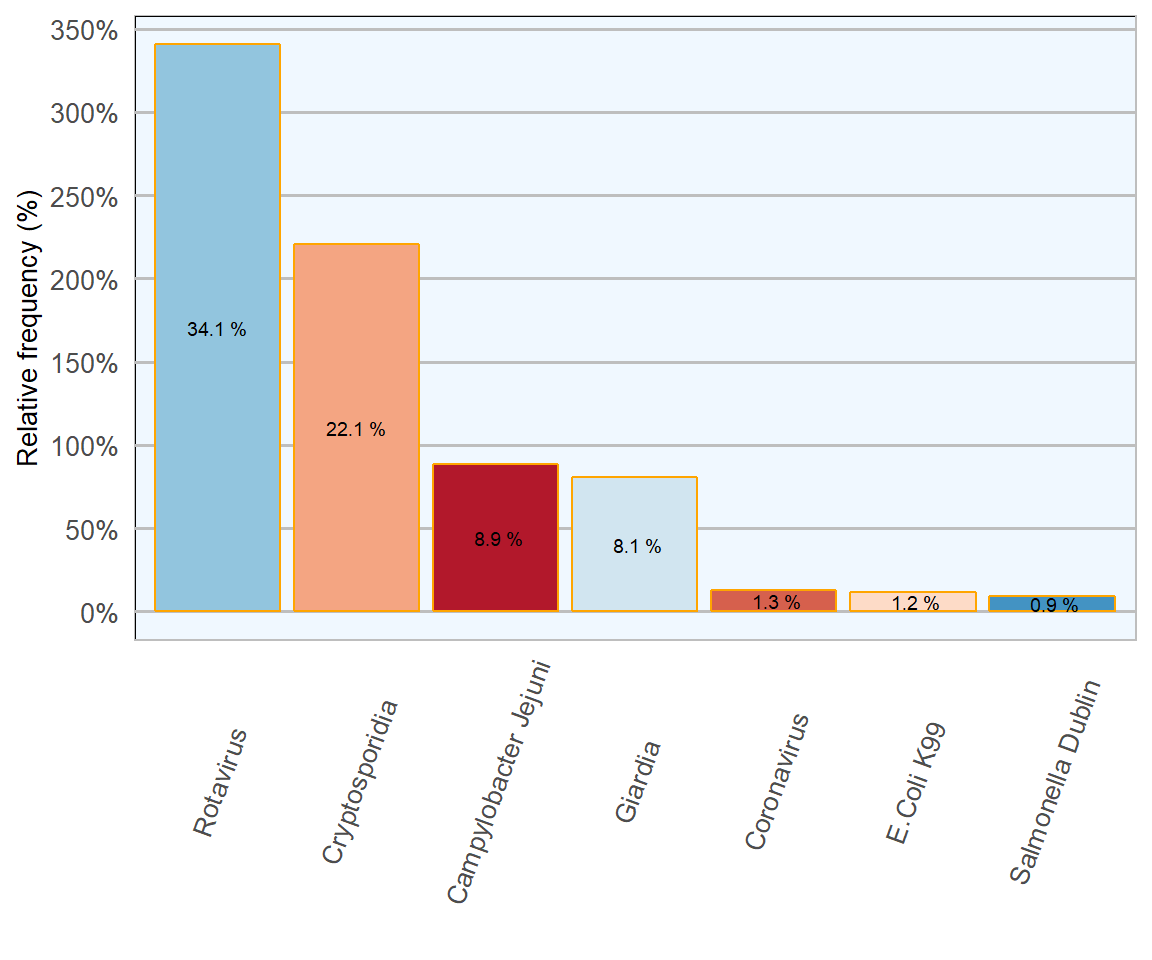

Approximately 1800 such faecal samples were examined in DAFM laboratories in 2018 (Table 4.1). This section shows the most common infectious agents diagnosed in calves less than one month old. The relative frequency of identification of pathogens in calf faecal samples in the Republic of Ireland in 2018 is plotted in Figure 4.2. Rotavirus and Cryptosporidium spp. were the most common pathogens identified while E coli K99, coronavirus and Salmonella Dublin were recorded relatively infrequently.

| Organism | No. of Tests | Positive | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotavirus | 1757 | 599 | 34.1 |

| Cryptosporidia | 1871 | 413 | 22.1 |

| Campylobacter Jejuni | 1644 | 146 | 8.9 |

| Giardia | 1080 | 87 | 8.1 |

| Coronavirus | 1763 | 23 | 1.3 |

| E.Coli K99 | 1299 | 15 | 1.2 |

| Salmonella Dublin | 1756 | 16 | 0.9 |

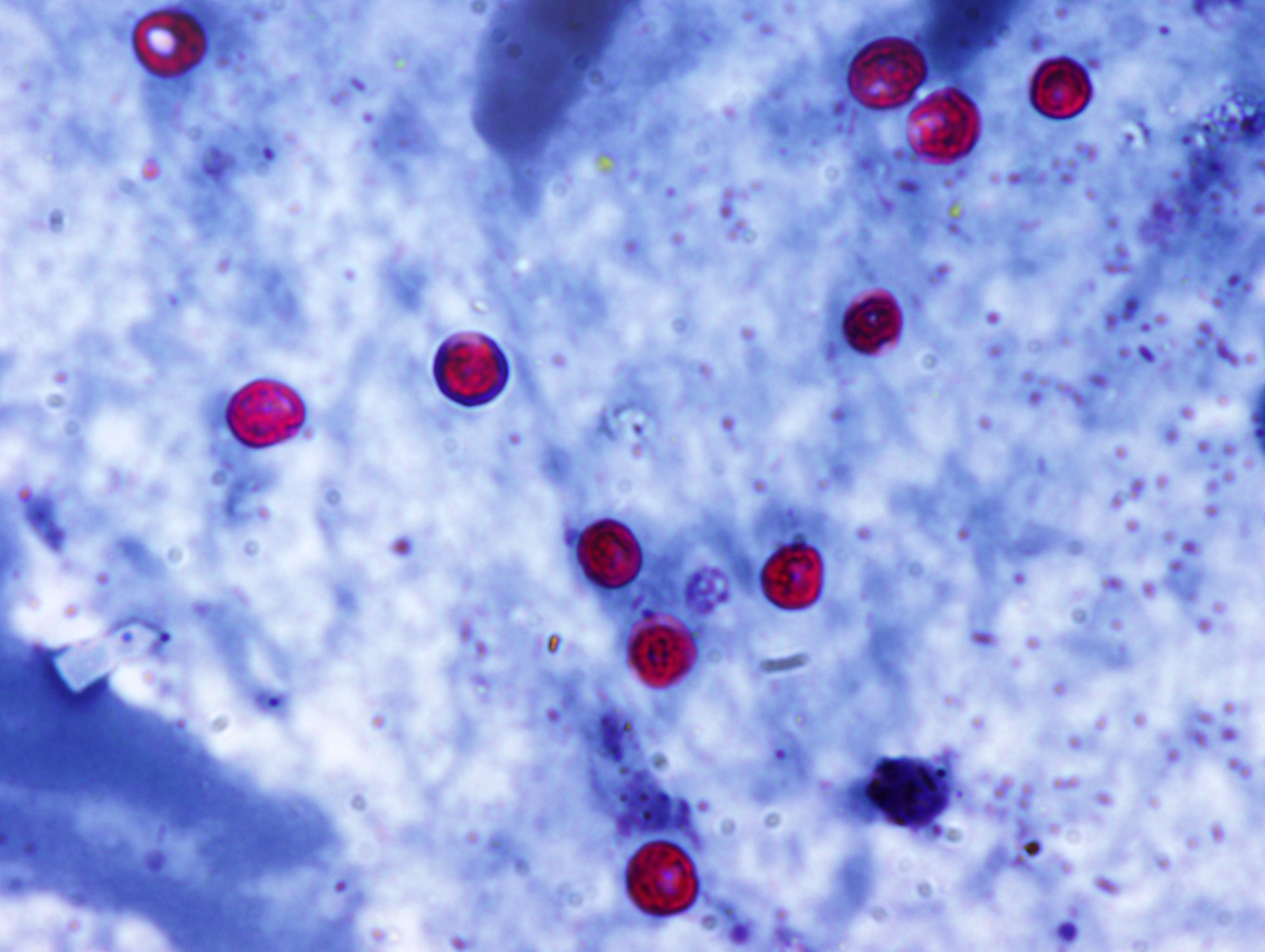

Figure 4.1: Cryptosporidial oocysts in a faecal smear, modified Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain. Photo: Cosme Sanchez-Miguel.

4.1.1 Rotavirus enteritis

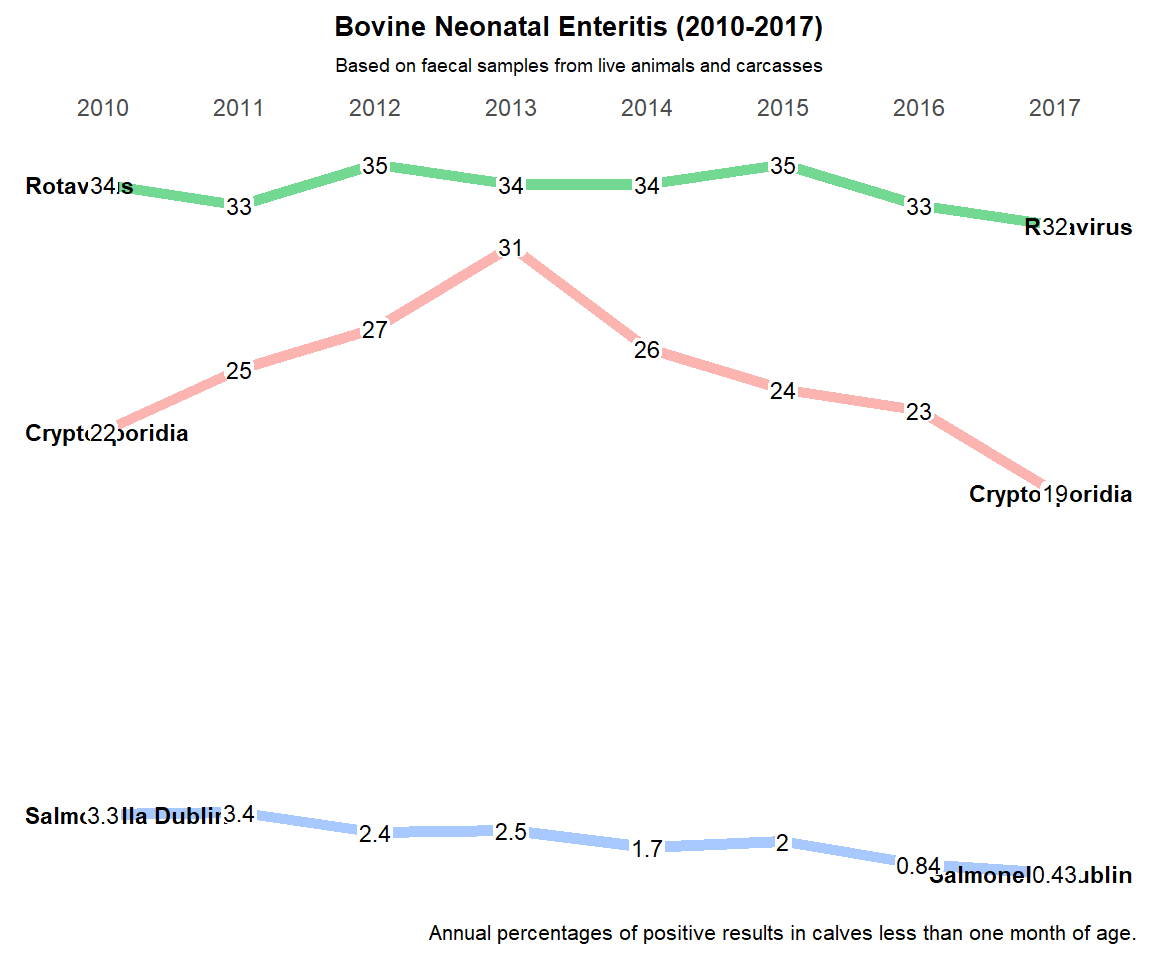

Rotavirus (34.09 per cent) has consistently been the most frequently identified pathogen in calf faecal samples in the Republic of Ireland in recent years, its frequency ranging from 30–35 per cent between 2010 and 2018 (Figure 4.4). Calves are most susceptible to rotavirus enteritis up to three weeks of age. Adult animals are the primary source of rotavirus infection for neonatal calves. The severity of clinical signs depends on several factors including the age of the animal and the immune status of the calf, the latter depends on the absorption of colostral antibodies immediately after birth. Rotavirus targets villi in the upper small intestine causing shortening and fusion of such villi, this results in malabsorption and leads to diarrhoea. Death may ensue due to acidosis, dehydration and starvation.

Figure 4.2: Bovine Neonatal Enteritis. Relative frequency of enteropathogenic agents identified in calf faecal samples tested in 2018.

4.1.2 Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium parvum is a small single-cell parasite which causes damage to intestinal epithelial cells of the lower small intestine resulting in mild to severe enteritis, typically affecting calves during their second week of life. Affected calves excrete large numbers of oocysts which are highly resistant and can survive in the environment up to several months under favourable conditions. Transmission between animals is by faecal-oral route, often via a contaminated environment. Control of the parasite is best achieved by strict maintenance of good calf housing hygiene practices and avoiding mixing animals of different ages. Ammonia-based disinfectants are most effective. The prophylactic use of drugs such as halofuginone lactate may also be useful. In addition to causing disease in animals, Cryptosporidium spp. has the potential to cause zoonotic disease especially in immunocompromised humans; therefore farm workers should take appropriate hygiene precautions when handling calves.

4.1.4 Escherichia coli K99

E. coli K99 is an enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and an important cause of neonatal enteritis in very young calves, typically less than three days of age. These strains of E. coli preferentially colonise the lower small intestine and produce toxins that cause secretion of water and electrolytes from the intestinal mucosa, resulting in rapid dehydration. The percentage prevalence of E. coli K99 would likely be higher if testing for this enteric pathogen was restricted to animals younger than one week old.

4.1.5 Salmonella Dublin

Salmonella enterica subsp.enterica serovar Dublin (Salmonella Dublin) is the most common Salmonella serotype that affects calves in the Republic of Ireland and was isolated in 0.91 per cent of neonatal faecal samples cultured in 2018. The relative frequency of detection of Salmonella Dublin from such cases has fallen significantly over the past decade from 3.4 per cent in 2011 to 0.9 per cent in 2018 (Figure 4.4). It is not clear why this has occurred. Salmonella Dublin infection has a number of clinical presentations in neonatal calves including acute enteritis, osteomyelitis and septicaemia/systemic disease. Salmonella enteritis is characterised by watery mucoid diarrhoea with presence of fibrin and blood. While Salmonella can cause diarrhoea in both adult cattle and calves, infection is more common and often more severe in calves from 10 days to 3 months old. In addition, calves can shed the organism for variable periods of time and/or intermittently depending on the degree of infection (carrier state).

The basic principles for the prevention and control of neonatal enteritis are enhancing host immunity and reducing the load of enteric pathogens in the environment. The importance of good colostrum management, leading to an adequate passive immunity transfer, in the prevention of calf diarrhoea is a given.

An average 40 Kg calf requires 3 litres of colostrum within 2–4 hours of birth. Thereafter, appropriate nutrition of young calves, including diarrhoeic calves, is essential. Calves should be grouped according to age on dry clean bedding and avoiding high stocking density. There should be good hygiene practices including appropriate disinfection between batches and rapid isolation and treatment of sick calves.

Colostral and milk antibodies against certain bacterial and viral enteric agents can be enhanced by vaccination of the cows during the dry period (passive immunisation).

4.1.6 Campylobacter jejuni

C. jejuni was found in almost 8.88 per cent of neonatal calf faecal samples tested in 2018. It is not considered pathogenic for cattle. However, it is routinely surveyed in neonatal faecal samples because it is a zoonosis and a major cause of gastroenteritis in humans. Therefore, appropriate hygiene precautions should be taken by personnel handling stock.

4.1.7 Giardia spp.

Giardia spp. is one of the most prevalent and widespread intestinal protozoan parasite in humans and several vertebrate animal species worldwide. The clinical significance of Giardia spp. as enteric pathogen in calves is questionable. While eight strains are recognized, only two strains are thought to be transferable to humans (A&B) and thus potentially zoonotic (Thompson 2004). Appropriate precautions should be taken by calf handlers.

4.1.8 Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria spp. Only three (Eimeria bovis, Eimeria alabamensis and Eimeria zuernii) out of twelve bovine coocidia species are pathogenic. Some of the non-pathogenic or weakly pathogenic species are capable of producing massive numbers of oocysts, therefore faecal coccidial occyst counts need to be interpreted in conjunction with history and clinical findings. Coccidia damage the epithelial cells lining of the gut causing diarrhoea and possibly dysentery.

| No. of Tests | Positive | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 610 | 107 | 18 |

Coccidiosis is particularly common in calves between three weeks and six months of age but it can occur in older animals also. Calves become infected when placed in environments contaminated by older cattle or other infected calves, e.g. indoors on bedding, outdoors around drinking and feeding troughs. Poor hygiene, high stocking density and poor health and nutrition will all contribute to a calf becoming infected. The frequency of detection of coccidiosis in neonatal calves less than 1 month old in the Republic of Ireland in 2018 was 18 per cent (Table 4.2).

Often, peak coccidia oocyst-shedding does not correlate with the onset of diarrhoea in calves. Detection of Coccidia spp. in faecal samples is facilitated by sampling pre-clinical comrade animals as well as those showing clinical signs.

Figure 4.3: Microphotography of coccidial oocysts in a faecal smear (faecal flotation). Photo: Cosme Sanchez-Miguel.

Figure 4.4: Trends in the incidence of Rotavirus, Cryptoporidia and Salmonella Dublin in calves less than one month old with neonatal enteritis.

References

Thompson, RC Andrew. 2004. “The Zoonotic Significance and Molecular Epidemiology of Giardia and Giardiasis.” Veterinary Parasitology 126 (1-2). Elsevier: 15–35.

A cooperative effort between the VLS and the SAT Section of the DAFM