Section 14 Disease of Pigs

- Shane McGettrick

- Senior Research Officer, Sligo Regional Veterinary Laboratory, Doonally, Sligo, Ireland

The Irish pig industry comprises 1.7 million pigs in approximately 1674 active herds. Two-thirds of these herds are made up by small scale producers who have less than six pigs, while there are 271 herds with greater than 100 pigs. The larger herds are intensively managed highly integrated systems whose private veterinary needs are provided by a relatively small group of specialist pig veterinarians. DAFM laboratories are attempting to increase the laboratory support to the pig industry through the provision of specialist laboratory expertise and continuing engagement with pig veterinary consultants and advisors. A primary focus has been surveillance for new and emerging diseases combined with an emphasis on the role of biosecurity in reducing risk of disease incursion and lessening impact of endemic disease in pig herds.

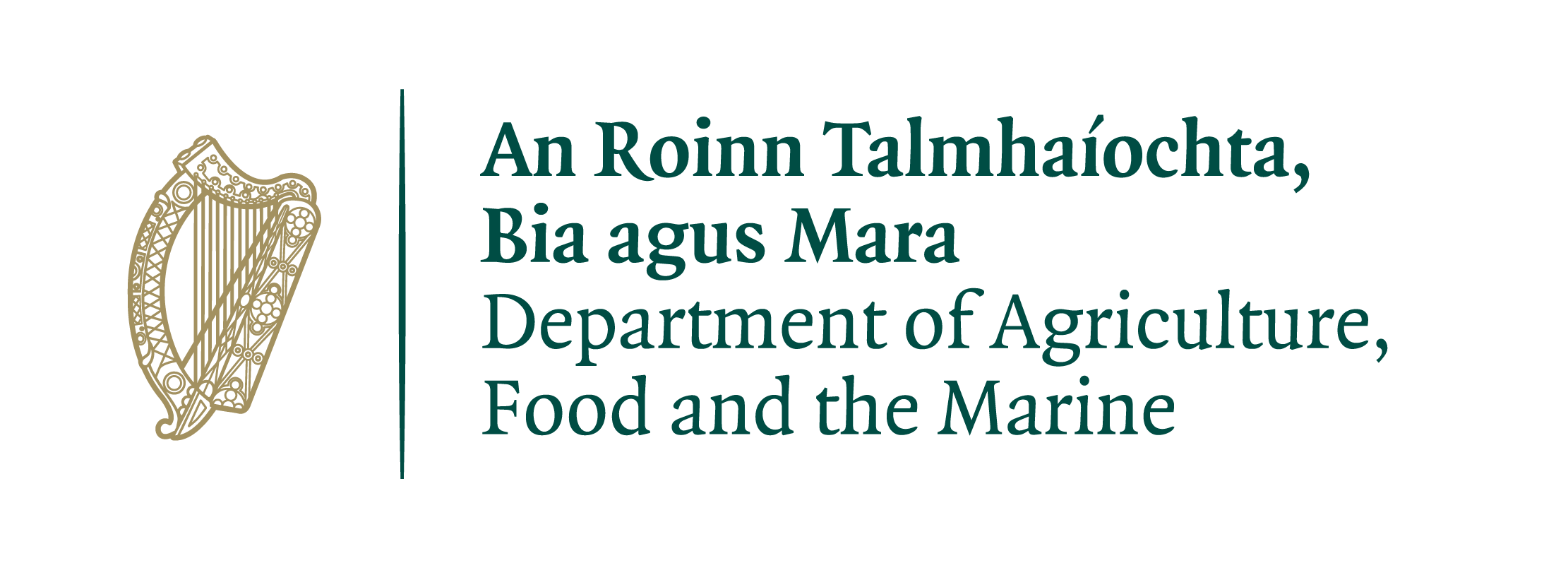

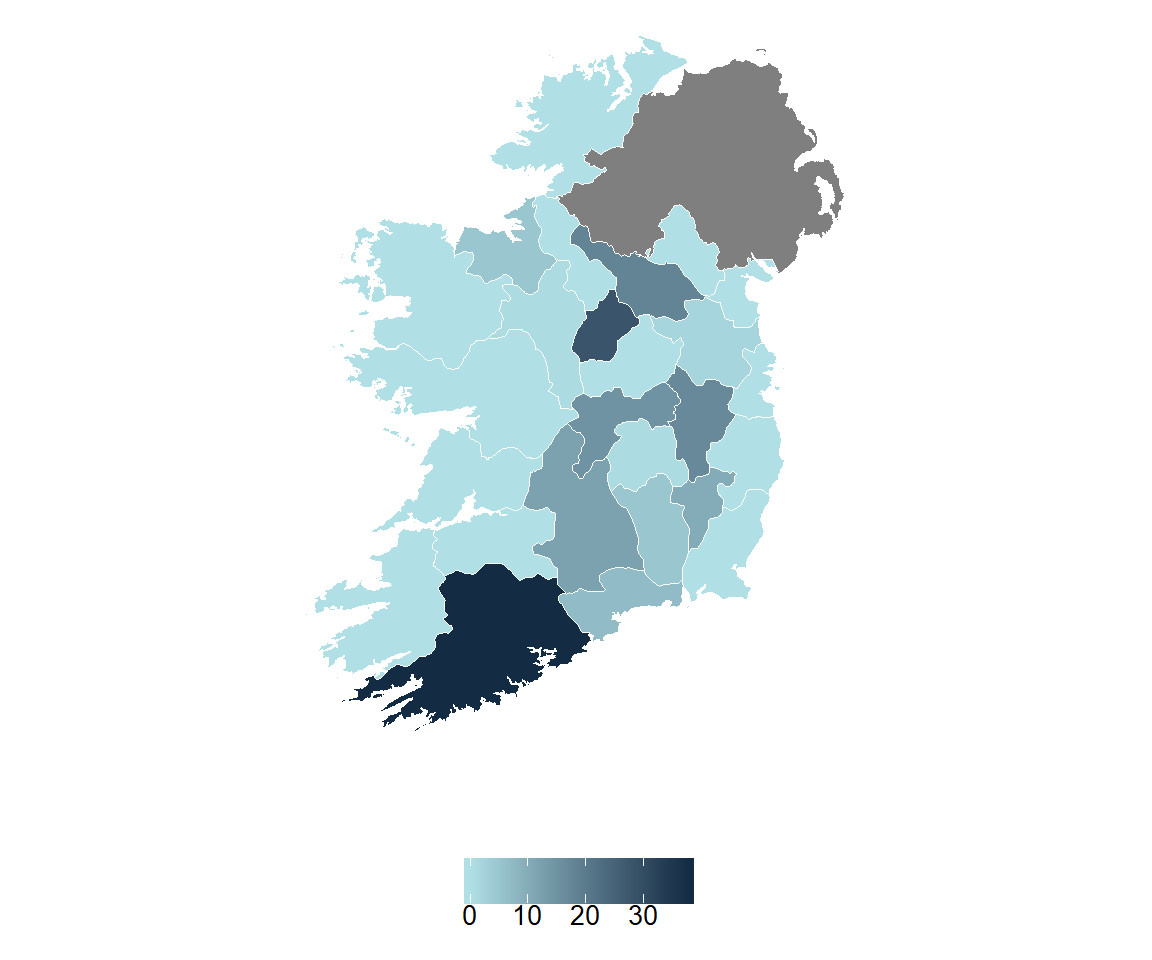

In 2018, DAFM laboratories carried out necropsy examinations on 164 pig carcases, while non-carcase diagnostic samples were submitted from 3201 pigs for various tests to assist veterinarians with disease investigation and/or surveillance on Irish pig farms. Figures 14.1 and 14.2 illustrate the number of pig carcases and diagnostic samples submitted from each county in 2018. The Irish pig population is not distributed evenly throughout the country; this is reflected in submission rates to laboratories, with the highest number of samples coming from counties with the highest pig populations.

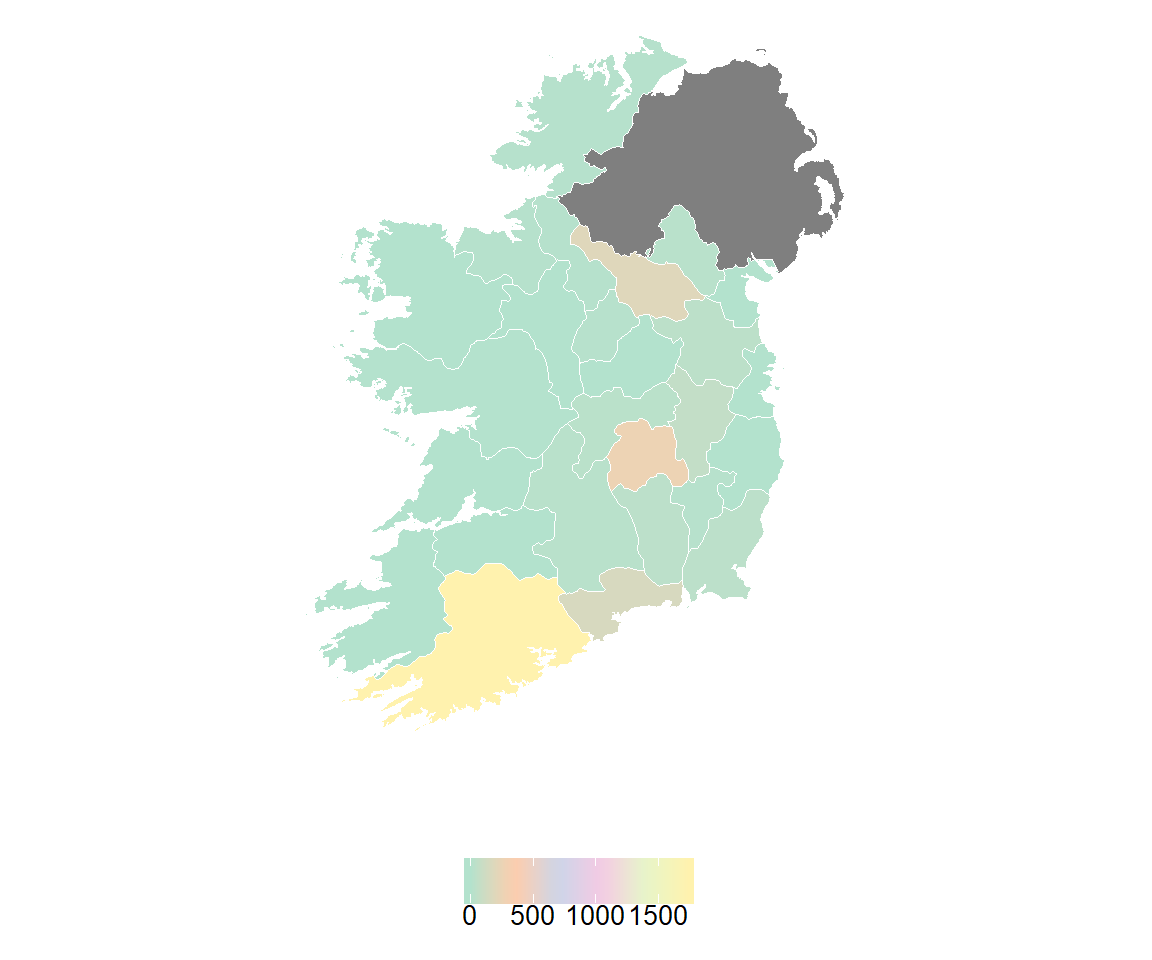

14.1 Post mortem diagnoses

The most frequent diagnoses in pig necropsy submissions during 2018 are detailed below. It should be understood that these reflect diagnoses in animals submitted to DAFM laboratories, rather than incidence of disease in the pig population, as many factors will influence the decision to submit an animal for necropsy.

Figure 14.1: Number of carcass per county submitted to the RVLs for post-mortem examination during 2018.

14.1.1 Gastrointestinal disease

Enteritis was the most frequent diagnosis in pig carcases submitted during 2018, the majority of these were in suckling pigs. Neonatal diarrhoea is a significant cause of morbidity and economic loss on Irish farms and necessitates the use of increased levels of antibiotics to reduce the impact of disease in the highly vulnerable intensive production systems. Neonatal piglets have reduced capacity to produce hypertonic urine, meaning that they are very susceptible to dehydration if the absorptive capacity of the gut is damaged. There are a wide number of agents implicated in neonatal pig diarrhoea; most common infectious agents identified in nursing pigs with diarrhoea are Clostridium perfringens, Rotavirus, E.coli, Cryptosporidia spp., Isospora suis and Clostridium difficile.

Porcine epidemic diarrhoea (PED), that caused devastating disease in the US during 2014, has not been detected in Ireland but is present in some European countries. Hence, disease surveillance in pigs showing enteric disease is ever more important. In undiagnosed outbreaks of diarrhoea, veterinary practitioners are encouraged to contact DAFM laboratories to avail of support and advice on sampling and diagnostic investigations, including detailed necropsy and histopathology.

Figure 14.2: Number of non-carcass diagnostic samples per county submitted to the RVLs during 2018.

Enteric disease is by far the most prevalent and significant health problem affecting neonatal pigs worldwide. Recent diagnostic investigations in Pathology and Virology Division in the Central Veterinary Research Laboratory (CVRL) and the emergence of so-called New Neonatal Porcine Diarrhoea Syndrome in Europe have shown that, in many cases, the aetiology of neonatal pig diarrhea is multifactorial and often cannot be attributed solely to the main pathogens traditionally associated with diarrhoea. It is likely that the relatively low diagnostic rate in these cases is due to a mixture of inadequate availability of diagnostic tests, emergence of novel agents, multi-pathogen infections, complex interactions between gut microbiome and environmental stresses. Inability to determine the underlying cause has implications in terms of control, antibiotic treatment, economic costs to the farmer, reputational damage to agricultural industry and decreased animal welfare. Absence of definitive aetiological diagnosis and misunderstanding of the relative contribution of various pathogens to disease pathogenesis and subsequent clinical signs may lead to the use of inappropriate treatments, particularly antibiotics, which is likely to contribute to development of antibiotic resistance.

| Diagnosis | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| GIT Infections | 24 | 26.1 |

| Systemic Infections | 17 | 18.5 |

| Diagnosis not reached | 16 | 17.4 |

| Respiratory Infections | 16 | 17.4 |

| CNS | 5 | 5.4 |

| Cardiac/circulatory conditions | 4 | 4.3 |

| Other | 3 | 3.3 |

| Reproductive Tract Conditions | 3 | 3.3 |

| GIT torsion/obstruction | 2 | 2.2 |

| Abcessation | 1 | 1.1 |

| Peritonitis | 1 | 1.1 |

Figure 14.3: Diseases diagnosed in pigs submitted for post-mortem examination to the RVLs in 2018 (n= 92 ).

14.1.2 Systemic disease

Rapidly growing pigs in weaner and finisher stages are susceptible to various bacterial diseases which are usually opportunistic infections that become established due to dietary change or other environmental stressors. Streptoccus suis and oedema disease due to toxin-producing E. Coli were frequent causes of systemic disease in pigs in 2018.

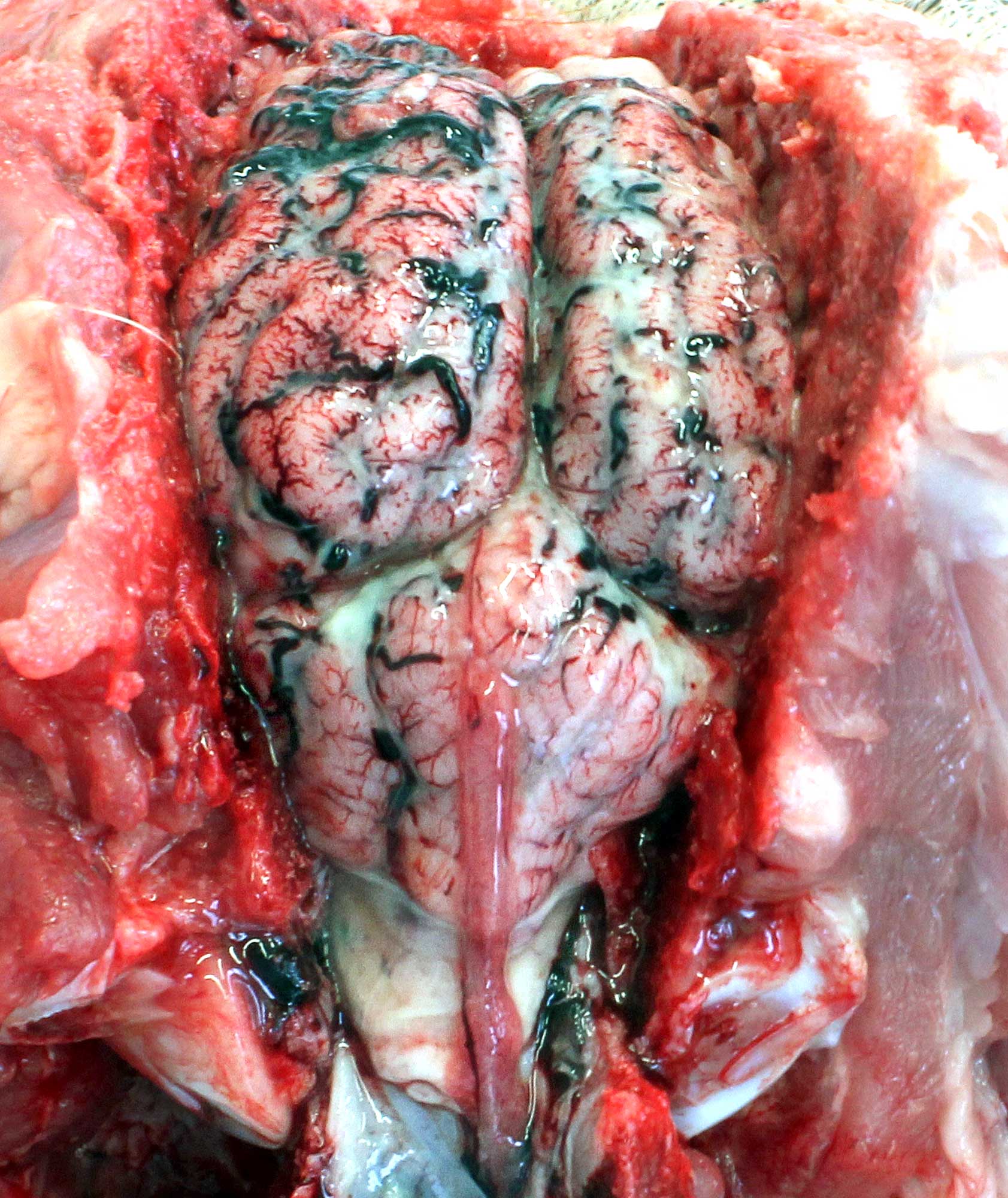

Figure 14.4: Fibrinosuppurative meningitis. Cranial view. Pale yellow-white exudate in the subarachnoid space, composed of neutrophils, fibrin and bacteria, and caused by Streptococcus suis type 2. Photo: Shane McGettrick.

14.1.2.1 Streptococcus suis

Most pigs carry Streptococcus suis in the upper respiratory tract, piglets are likely to have been infected by their mothers. However, few carry the virulent strains capable of causing disease. An outbreak of disease is likely to occur when subclinical carriers of virulent strains are introduced into a population; this was considered the most likely method of transmission in cases described below where management systems included mixing and movement of pigs between groups. The severity of disease, even when the virulent strain is present, is variable and thought to be dependent on the presence of other stress factors including concurrent disease, high stocking density, environmental stress and recent mixing. Cases described below were considered relatively unusual in that the presentation was acute rather than the more insidious onset of disease expected. Environmental and management factors were likely to have been significant factors in the occurrence of disease.

In 2018 DAFM laboratories investigated various increased mortality events in weaner and finisher pigs in large scale commercial pig units. In one such case, clinical history was of pigs weighing 15–30 Kg dying suddenly without any observed illness. No management change was identified but severity was considered worst in younger pigs and disease developed within two weeks of entering the second stage weaner facilities. The unit did not operate an all-in-all-out policy in weaner and fattener houses; instead it batched pigs on basis of weight. Pigs submitted for necropsy were in good condition although there was marked reddening of ventral neck and abdomen noted in all cases. Necropsy revealed similar findings in all pigs examined; variable interlobular pulmonary oedema and excess straw coloured fibrinous pericardial, pleural and abdominal fluids. The meninges of all pigs were considered cloudy on gross examination (Figure 14.4) and an acute fibrinosuppurative meningitis was confirmed by histopathology. Streptococcus suis was isolated in all pigs from multiple organs including brain.

Streptococcus suis was identified as the cause of severe acute polyarthritis in early stage fattener pigs in another farm. Clinical signs included sudden increase in lameness and ill thrift. Necropsy identified severe acute fibrinosuppurrative arthritis affecting multiple joints with associated soft tissue oedema and swelling. Diagnosis was confirmed by pure growth cultures of streptococcus suis from joint material.

14.1.3 Respiratory disease

Respiratory disease in pigs is a cause of ongoing production loss in many pig units. In 2018, DAFM laboratories continued its ongoing collaboration with research partners in investigating causes of respiratory disease on Irish pig farms. Results from this work are being disseminated to the industry.

An example of a respiratory disease case investigation during 2018 was where a number of pigs were submitted following a rapid increase in mortality in a large commercial pig herd. Late stage weaners and early stage fatteners were reported as dying following acute respiratory illness. Marked reddening of ventral body areas was reported consistently and the farmer recorded 1–2 pigs dead or dying each morning in affected batches. Six pigs submitted for necropsy were diagnosed with pleuritis. There was severe diffuse fibrinous pleuritis and pericarditis with large amounts of fresh fibrin deposited on thoracic serosal surfaces. Pulmonary lesions were considered extremely severe with diffuse consolidation of 80–90 per cent of lung parenchyma and marked necrosis of parenchyma in diaphragmatic lobes in all pigs. There was mild excess of abdominal fluid and small amounts of fibrin in some pigs. Other serosal surfaces, including joints and meninges, were unremarkable. Distribution and severity of lesions were consistent with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (APP) infection, which was later confirmed by culture and histopathology.

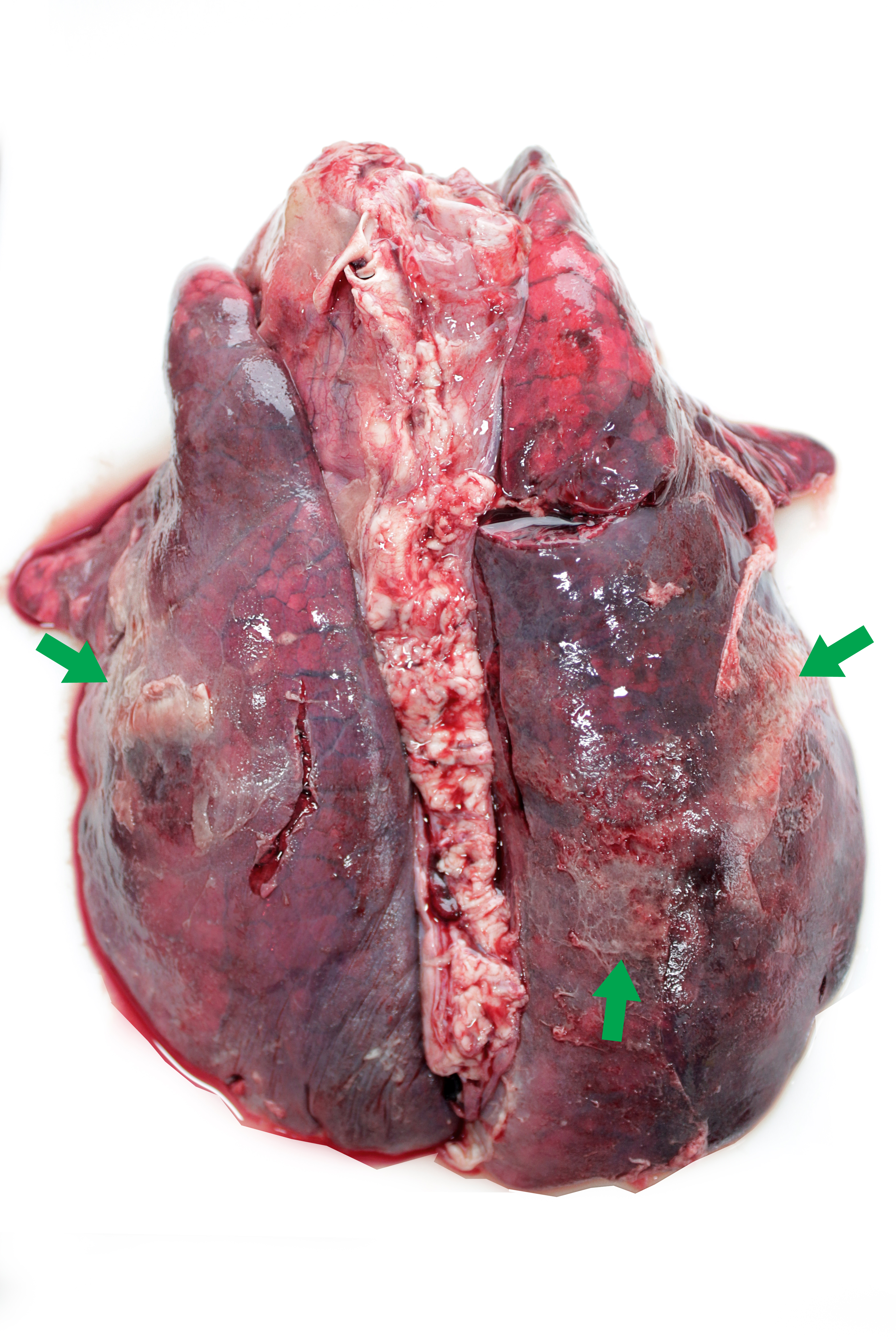

Figure 14.5: Porcine pleuroneumonia. Fibrinous bronchopneumonia caused by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, characterised by severe pulmonary consolidation and fibrinous exudate on pleural surface (green arrows) mainly affecting the caudal lobes. Photo: Cosme Sánchez-Miguel.

APP is a relatively commonly diagnosed cause of pneumonia in pigs (Figure 14.5). Severe outbreaks may occur in naive populations causing a rapidly fatal pleuropneumonia. Source of infection is likely to be previously infected pigs where organisms remain as sequestra in pulmonary parenchyma or in tonsils and nasal cavity. There is marked differences in virulence of strains and disease is difficult to eradicate from herds. Severity of the disease is dependent both on the virulence of the train and the infectious dose. In experimental conditions death has occurred as rapidly as 3 hours post inoculation.

14.2 Notifiable disease

14.2.1 African swine fever awareness

The current outbreak of African swine fever (ASF) in Europe poses a risk to the Irish pig industry (Sánchez-Cordón et al. 2018). The disease, which has been increasingly identified over the past year in wild boar and commercial pig farms in Eastern Europe, was identified in wild boar populations in southern Belgium in 2018. The most significant risk factor for entry into Ireland is feeding illegally imported infected pork products to pigs. During 2018, DAFM veterinary laboratory service placed a strong emphasis on preparation and contingency planning to mitigate risk from a potential incursion of exotic disease such as ASF through increased training of staff on outbreak investigations and pig sampling techniques.

ASF is a notifiable disease and PVPs are reminded to notify DAFM if they suspect presence of the disease by contacting their local RVO or the National Disease Emergency Hotline at 1850 200 456. An ASF factsheet for vets detailing the clinical signs of ASF is available on the African swine fever page on the DAFM website. DAFM also produced a biosecurity leaflet specifically aimed at non-intensive pig farms and an ASF factsheet for farmers, both are available to download from the African swine fever page on the Department website.

Non-intensive or smaller pig herds as well as pet pig owners, may have irregular veterinary input and are likely to contact their local veterinary practitioner for advice when faced with unexplained clinical signs or deaths. DAFM laboratories are aware of the difficulties in reaching a diagnosis in these cases, especially for veterinary practitioners who may not have previous experience in treating or diagnosing the range of disease that may be present in pigs. All practitioners are reminded that, in any relevant pig disease outbreak, DAFM laboratories are available to offer advice on sampling and will carry out necessary testing, including necropsy free of charge, in order to confirm a diagnosis.

Practitioners are also advised to encourage clients with small pig herds to submit any dead or fallen carcases to the DAFM laboratory network, as this will provide valuable disease surveillance material and will allow the submitting vet to assist in diagnosis and management of disease within the herd.

References

Sánchez-Cordón, P.J., M. Montoya, A.L. Reis, and L.K. Dixon. 2018. “African swine fever: A re-emerging viral disease threatening the global pig industry.” The Veterinary Journal 233: 41–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.12.025.

A cooperative effort between the VLS and the SAT Section of the DAFM