Image 1: A Bank's Primary Stakeholders; own illustration.

Group Members:

Submitted on July 22, 2022.

# install required packages

!pip install lime --quiet

!pip install alibi --quiet

!pip install shap --quiet

!pip install lime-stability --quiet

!pip install xgboost --quiet

!pip install --upgrade xgboost

Looking in indexes: https://pypi.org/simple, https://us-python.pkg.dev/colab-wheels/public/simple/ Requirement already satisfied: xgboost in /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages (1.6.1) Requirement already satisfied: numpy in /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages (from xgboost) (1.21.6) Requirement already satisfied: scipy in /usr/local/lib/python3.7/dist-packages (from xgboost) (1.7.3)

# required packages

# at the beginning we make sure to consider all necessary packages

## Standard packages

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import sklearn

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time

## Feature Engineering

import datetime # Transform date features

import seaborn as sns # corelation matrix

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # Scaling Data

## Used Models

### Logit

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

### xgboost

import xgboost as xgb

## Validation of model

from sklearn import metrics

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, f1_score,confusion_matrix

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

## Interpretability methods

### SHAP

import shap

### LIME

import lime

from lime.lime_tabular import LimeTabularExplainer

from lime_stability.stability import LimeTabularExplainerOvr

from lime_stability.utils import LocalModelError

### ANCHORS

from alibi.explainers import AnchorTabular

The widespread use of computational algorithms in various industries in the recent decade confirms a transformation of business processes towards a more computation-driven approach (Visani et al. 2022). Simple methods, the most famous being Linear Regression and Generalized Linear Models (William H. Greene 2003), have been followed by the advent of powerful computing tools, leading to the development of more sophisticated machine learning techniques. In particular, machine learning models can perform intelligent tasks usually done by humans. In combination with the huge availability of data sources and increased computational power, machine learning techniques have reduced the time to achieve more accurate results. Despite these advantages, machine learning models display weaknesses especially when it comes to interpretability, i.e., “the ability to explain or to present the results, in understandable terms, to a human” (Hall and Gill 2019). This issue is mainly caused by large model structures and huge numbers of iterations involved in machine learning algorithms combined with potentially many mathematical calculations, hiding the logic underlying these models and making them hard to grasp for humans. Consequently, a substantial amount of techniques have been proposed in the recent literature to make these models with an increased complexity more understandable for humans (Visani et al. 2022). Considering the importance of interpretability with a local focus i.e. trying to explain a single prediction, this paper investigates various aspects of interpretability and the challenges involved in implementing the corresponding methods within the credit risk industry. In particular, three different techniques are employed: LIME (Local Interpretable Model Agnostic Explanations), SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations), and the less common approach Anchor.

Article 8 of the European Union’s (EU) Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union stipulates the right of "Protection of personal data" (European Union 2012). Building on this fundamental right, the EU passed Regulation (EU) 2016/679, better known as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in 2016. The regulation, which has been legally binding since 2018, aims to "strengthen individuals' fundamental rights in the digital age”. At the same time, according to the regulation, model performance should not be the sole criterion for the suitability of a machine learning. (European Commission 2022) Recital 71 expands on this point and specifically states that the "data subject [author's note: respective individual] should have the right not to be subject to a decision, which may include a measure, evaluating personal aspects relating to him or her which is based solely on automated processing and which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her, such as automatic refusal of an online credit application or e-recruiting practices without any human intervention. [...] In any case, such processing should be subject to suitable safeguards, which should include specific information to the data subject and the right to obtain human intervention, to express his or her point of view, to obtain an explanation of the decision reached after such assessment and to challenge the decision." (European Parliament and the Council 2016) Article 22 manifests the right to "not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing [...] [and] at least the right to obtain human intervention on the part of the controller, to express his or her point of view and to contest the decision." (European Parliament and the Council 2016) In addition, article 14 requires that the individual is provided with "meaningful information about the logic involved, as well as the significance" in order to "ensure fair and transparent processing" of personal data. (European Parliament and the Council 2016) This contradicts the approach of many common supervised machine learning algorithms, which rely purely on statistical associations rather than causalities or explanatory rules to produce out-of-sample predictions (Goodman and Flaxman 2017).

Similarly, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2022) clarified that the rights set out in the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (Regulation B) also apply to decisions based on “complex algorithms”. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (Regulation B) prohibits adverse actions such as the denial of a credit application on the basis of discriminatory behavior and grants credit applicants against which an adverse action has been taken the right to obtain a statement rationalizing this adverse decision.(Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection 2011) The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2022) unequivocally formulates that the law does "not permit creditors to use complex algorithms when doing so means they cannot provide the specific and accurate reasons for adverse actions.” (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 2022) The development of interpretable algorithms is therefore not only desirable but a legal necessity.

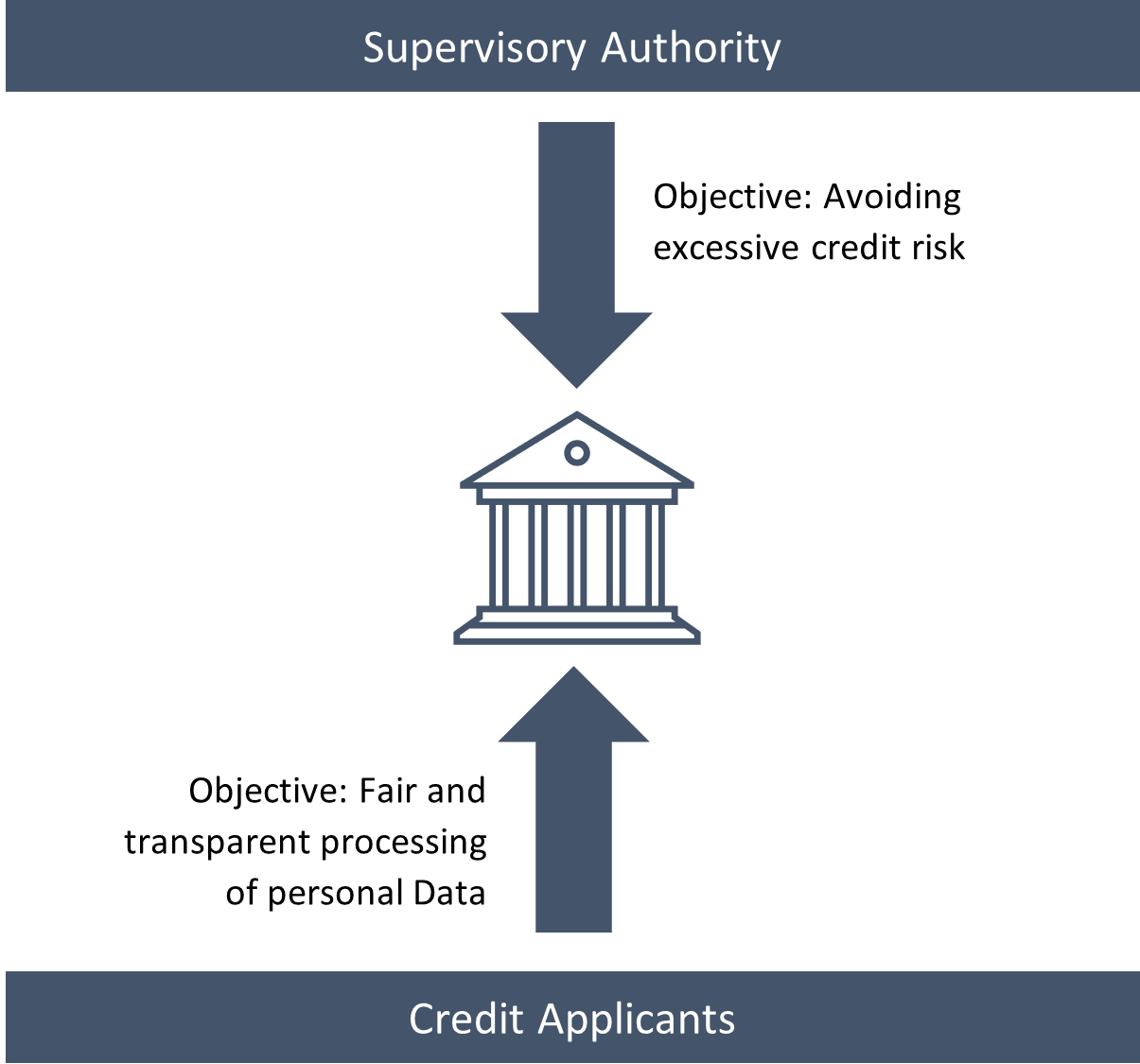

It is evident that a bank's objective is to maximize its franchise value. The minimization of its credit risk plays a key role in this regard. The bank will hence try to reduce credit default as far as possible by screening credit applicants. Banks therefore benefit from models that predict the probability of default for a credit applicant based on observable factors. For this reason, machine learning approaches are in principle also highly interesting for banks. At the same time, model performance is not the sole criterion for the suitability of a machine learning algorithm for the use in the banking sector since the bank must also satisfy its stakeholders. The most important stakeholders in this context are a) the bank's credit applicants and b) the supervisory authority that regulates banks.

Image 1: A Bank's Primary Stakeholders; own illustration.

The considerations on the customer side have already been addressed in the section on legal implications: Credit applicants have a right to know the reasons why their credit application was (not) granted. At the same time, the topic is currently gaining relevance from a regulatory standpoint: For example, the Deutsche Bundesbank and BaFin (2021), the two central supervisory authorities of German banks, warned in a consultation paper of increased model risk due to the black-box nature of many machine learning techniques and called for a focus on interpretability. (Deutsche Bundesbank and BaFin 2021) Responses to the consultation paper indicated that respondents in the banking and insurance industry believe that the main benefit of interpretable models is to facilitate model selection by allowing the validity of the model to be verified by a human with domain knowledge. At the same time, the consultation highlights that the implementation of interpretable models is considered cost-intensive and therefore only worthwhile undertaking if the effort is counterbalanced by a significant increase in performance. (Deutsche Bundesbank and BaFin 2022)

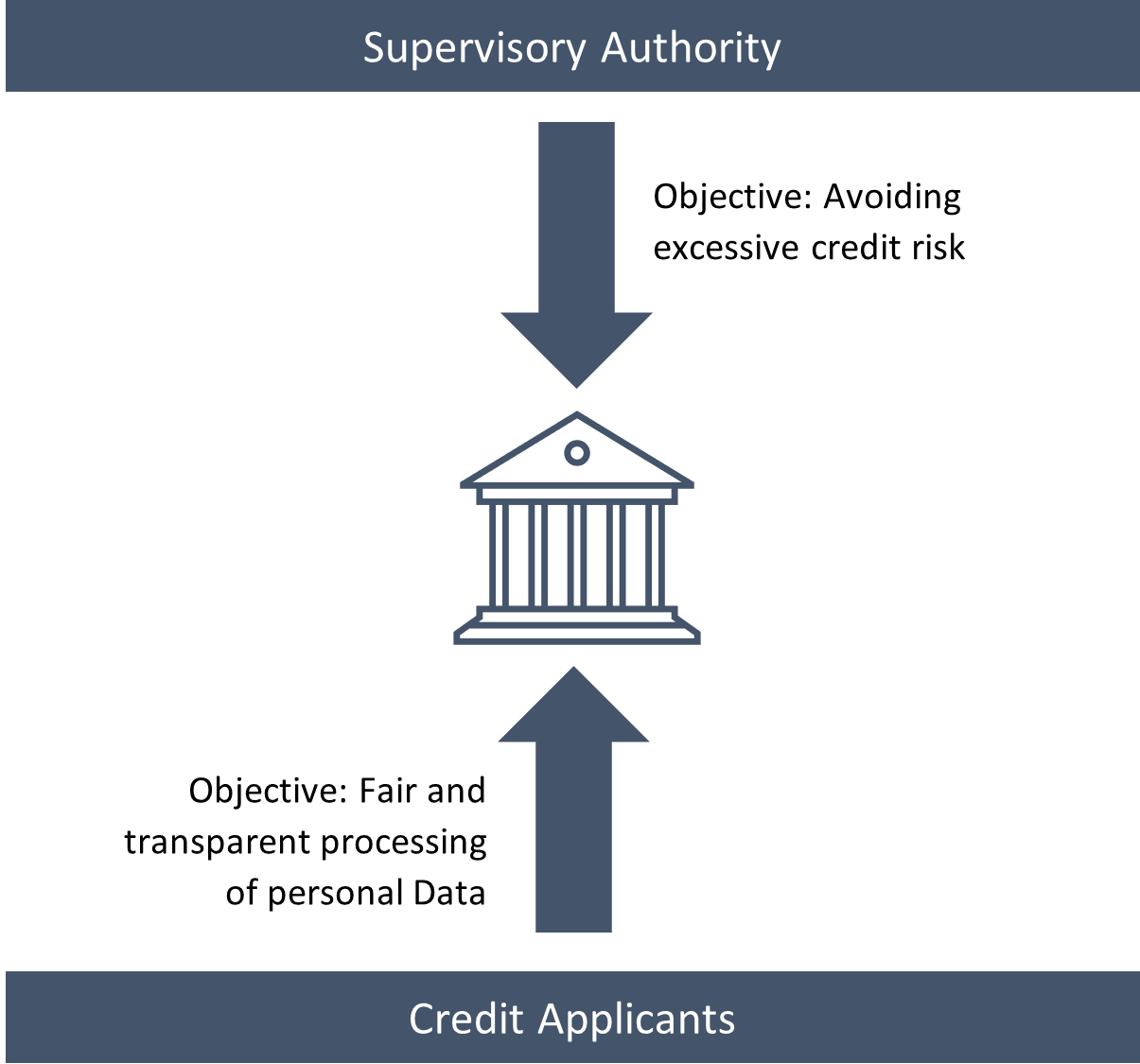

Lipton (2016) clarifies that no universal definition of the term "interpretability" exists. Rather, machine learners seek different underlying goals when searching for interpretable algorithms. His taxonomy identifies five dimensions users wish to achieve through the application of interpretable models (see Figure 2):

Trust is partially covered by model performance: The higher a model’s predictive accuracy the less false predictions it makes and the more a user can rely on the model’s predictions. However, there is more to trust then just accuracy. First, there is a psychological component: Humans may tend to have more faith in a model they are able to grasp intellectually. Second, an algorithm may be perceived as more trustworthy if it makes wrong judgement in cases in which a human decision maker would have misjudged as well as in such cases human intervention would have failed to yield an improvement. (Lipton 2016) The more severe the consequences of a model decision, the more important trust becomes. (Ribeiro et al. 2016)

Another component of interpretability is the ability to establish causal relationships between the features and the target. In standard supervised learning techniques this is problematic. Thus, inducing causal relationships in a machine learning context is a research branch in its own right.

In addition, one would ideally want to train a machine learning model that can be applied to new data without significant performance loss. Data scientists usually try to achieve this by partitioning a given dataset into a test and training dataset. Within this context, a model is thus deemed transferable if it is able to predict the test data given what it has learned about the data’s underlying structure though studying the training dataset. In contrast to this rather narrow definition of transferability, a human decision maker typically performs better at generalizing previously obtained knowledge and applying it to entirely new context. (Lipton 2016) Here, a similar reasoning can be applied as in the case of the dimension "Trust": A model appears interpretable to humans if it is evident how the model applies known principles to new situations and if it fails to do so in scenarios in which a human would fall short as well.

The fourth dimension is the desire for a model to be as informative as possible to benefit decision makers to the maximum degree possible.

Lastly, ethical considerations constitute grounds for the use of interpretable models. Users wish to ensure that model-based decisions are made in a manner that the user, supervisor or society deems ethical. (Lipton 2016)

Image 2: The Five Dimensions of Interpretability; own illustration based on Lipton (2016).

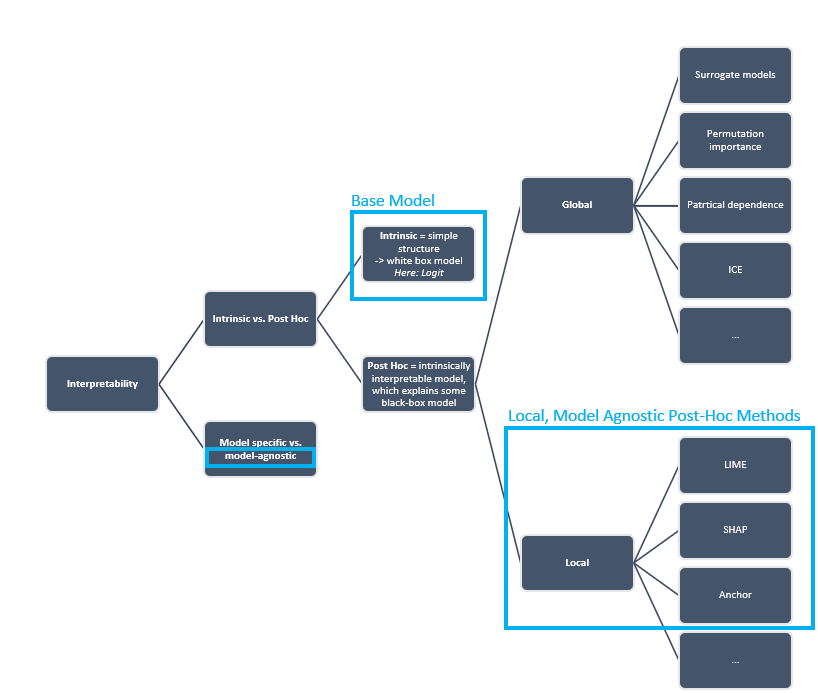

Given the research question of this paper, the question arises which dimensions of Lipton’s (2016) interpretability taxonomy are of particular relevance in the area of credit risk and how the term should be defined in our given context. Considering the main stakeholders of a bank, we find the dimensions “Trust” and “Informativeness” to be of particular relevance. Trust in the credit risk context is strongly related to credit risk reduction but goes beyond it. In addition to good predictive power (and thus low credit default probability), there must also be a sense of security among stakeholders that the model is drawing its predictions on the basis of meaningful conclusions. In addition, models must be as informative as possible in order to plausibly communicate decisions to stakeholders. To illustrate this point, imagine a situation in which a credit applicant has been classified as not creditworthy on the basis of a machine learning algorithm. Naturally, the credit applicant will expect a plausible explanation for this. An interpretable machine learning technique should provide credit officers, who have to advocate model decisions in front of credit applicants, with all the necessary information. Our definition of "interpretability" is thus strongly geared to the needs of the end user. For the purposes of this paper, we thus adopt the definition of “interpretability” by Ribeiro et al. (2016) who classify an explanation as interpretable if it generates a “qualitative understanding [of the relationship] between the input variables and the response”. They aim at a model that can support human decision makers by making predictions and providing rationales for them. The human, who acts as the final authority in the decision-making process, then evaluates the model's predictions and justifications, and uses his or her domain knowledge to decide whether the decision is conclusive. (Ribeiro et al. 2016)

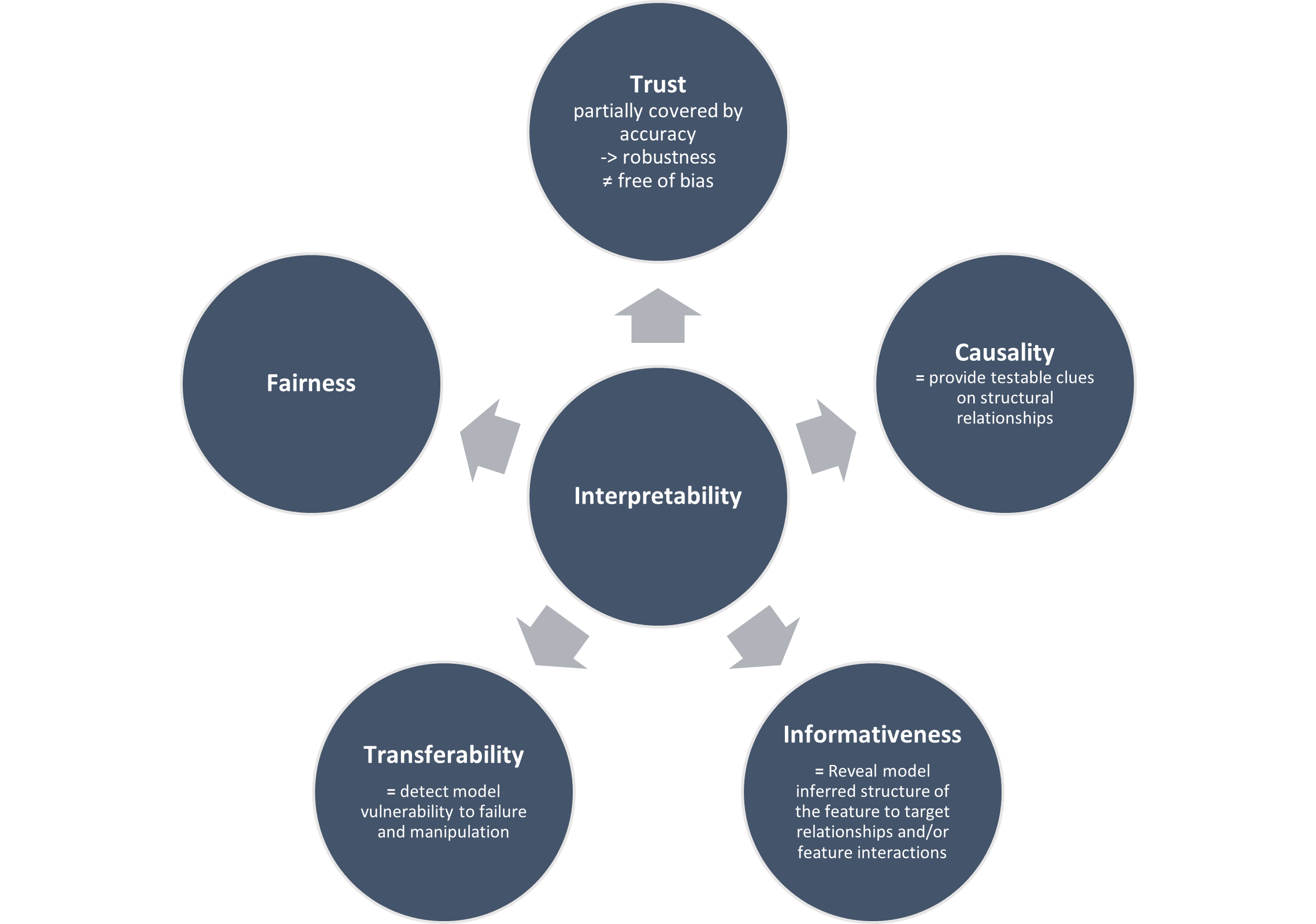

Having outlined the importance of interpretable machine learning models in general and in particular in credit risk, one must ask in which way interpretability can be achieved. Figure 3 gives a high-level overview. Most fundamentally, machine learning models can be divided into intrinsically interpretable models (so-called white-box-models) and black-box-models.

Intrinsically interpretable models are – as the name suggests - in themselves interpretable and thus do not require further adjustments to deliver interpretable explanations. For a model to be intrinsically explainable, it therefore needs to be sufficiently simple for a human to be able to grasp it. For example, linear regression, logistic regression and a shallow decision tree can be considered intrinsically explainable models.

A model that is not inherently explainable requires co-called post-hoc methods to render its results explainable ex-post. These post-hoc methods fall into one of two categories: They are either model-specific or model-agnostic. As the name suggests, model-specific interpretable machine learning algorithms are tailored towards specific model classes. Model-agnostic methods, on the other hand, are suited for any class of model. A further distinction can be made with regard to the scope of the interpretation offered by the post-hoc method: Does the explanation cover the entirety of the model’s decision behavior and can thus explain according to which principles the models arrive at its conclusions? Or does the explanation offered concern a single observation and can thus explain the conclusions drawn by the models for any particular case? The latter of these options is called “local interpretability” while the former is referred to as “global interpretability”. (Molnar 2022)

Image 3: Overview of Interpretability Methods; own illustration.

# Add Literature Table

file_name = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Group2Interpretability/\

APA_Interpretability/main/Input/LiteratureTable.csv'

Literature_Table = pd.read_csv(file_name,index_col=False, sep=";")

pd.set_option('display.max_colwidth', None)

dfStyler = Literature_Table.style.set_properties(**{'text-align': 'left'})\

.hide_index()

display(dfStyler.set_table_styles([dict(selector='th',

props=[('text-align', 'left')])]))

print("-----------------------------------------------------------------------")

print("Table 1: Literature Overview, Interpretability Methods.")

| Source | Title | Local vs. Global Interpretability | Data | Methodology | Key Insights/Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baesens et al. (2003) | Using Neural Network Rule Extraction and Decision Tables for Credit-Risk Evaluation | Local | German credit risk dataset from UCI repository (Dua and Graff 2019) and two datasets obtained from major Benelux financial insti- tutions. | Neural Network Rule Extraction Techniques (Neurorule, Trepan, and Nefclass) and Decision Tables | Usefulness of Neural Networks due to their universal approximation property. Conclusive rules extracted by Neurorule and Trepan. Use of Decision Table to visualize reules in an intuitive graphical format. |

| Bussmann et al. (2019) | Explainable AI in Credit Risk Management | Local & Global | Lending Club data set obtained from Kaggle | Logistic Regression, XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Neural Network + Post-hoc Explanability using LIME and SHAP | LIME and SHAP deliver logical and consistent explanations |

| Bussmann et al. (2021) | Explainable Machine Learning in Credit Risk Management | Local & Global | Data obtained from Modefinance, a European Credit Assessment Institution (ECAI) | XGBoost + Post-hoc Explanability using TreeSHAP (cf. Lundberg et al. 2020) | "explainable AI models can effectively advance the understanding of the determinants of financial risks and, specifically, of credit risks." |

| Demajo et al. (2021) | An Explanation Framework for Interpretable Credit Scoring | Local & Global | Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) and Lending Club (LC) Datasets | XGBoost + Post-hoc Explanability using SHAP+GRIP, Anchors and ProtoDash; Interpretability judged by domain experts | Domain experts judged that "the three types of explanations provided are complete and correct, effective and useful, easily understood, sufficiently detailed and trustworthy." |

| Dumitrescu et al. (2022) | Machine learning for credit scoring: Improving logistic regression with non-linear decision-tree effects | Local | Simulated Data and Two Real Datasets | Logistic Regression + Decision Trees | Improvement in predictive power while maintaining its interpretability |

| Hayashi (2016) | Application of a rule extraction algorithm family based on the Re-RX algorithm to financial credit risk assessment from a Pareto optimal perspective | Global | Australian Credit Dataset, German Credit Dataset (Dua and Graff 2019) and two datasets obtained from major Benelux financial institutions. | Neural Network + Recursive rule extraction using the Re-RX algorithm family | "Continuous Re-RX, Re-RX with J48graft, and Sampling Re-RX comprise a powerful management tool that allows the creation of advanced, accurate, concise and interpretable decision support systems for credit risk evaluation." |

| Lundberg & Lee (2017) | A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions | Local | - | SHAP as additive feature importance method using Shapley values | SHAP framework identifies the class of additive feature importance methods (which includes six previous methods) and shows there is a unique solution in this class that adheres to desirable properties. |

| Lundberg et al. (2020) | From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees | Local & Global | chronic kidney disease data from the CRIC study. | Shapley values + TreeSHAP + SHAP interaction values | SHAP Extention by offering many tools for model interpretation that combine local explanations, such as dependence plots, summary plots, supervised clusterings and explanation embeddings. |

| Molnar (2018) | Interpretable machine learning: A guide for making black box models explainable. | Local & Global | - | summarizes all actual explainable ML tools | summary of all possible Explainable methods |

| Ribeiro et al.(2016) | "Why Should I Trust You?" Explaining the Predictions of any Classifier | Local and Global | Multi-polarity and Religion dataset available at their Github | LIME used on Deep Networks for Images and SVM for Text Data | Introduces LIME with the goal of local interpretability and SP LIME to measure global interpretability. The former is done by approximating the black box model using an interpretable model and the latter is proceeded via choosing representative observations from the data to provide a global view of the model. The paper moves toward achieving interpretability with the ultimate goal of gaining trust in ML models. |

| Ribeiro et al. (2018) | Anchors: High-Precision Model-Agnostic Explanations | Local | lending dataset & rcdv dataset | Usage of the anchor method on tabular data and image data to evaluate it's working method | Anchors highlight the part of the input that is sufficient for the classifier to make the prediction, making them intuitive and easy to understand. |

| Uddin et al. (2020) | Leveraging random forest in micro‐enterprises credit risk modelling for accuracy and interpretability | Global | micro-enterprises data obtained from one of the leading commercial banks of China | Random Forst + Relative variable importance | Essentiality of traditional financial variables and Relevance of alternative predictors (such as macroeconomic conditions) whos inclusion enhances existing modelling approaches |

| Visani et al. (2022) | Statistical stability indices for LIME: Obtaining reliable explanations for machine learning models | Local | An anonymised statistical sample, obtained by pooling data from several Italian financial institutions | Investigating LIME stability by performing repeated calls and comparing the results | Definition of LIME, especially the specification of kernel and the model's comlexity measure alongside with the method's feature choice makes the model strongly prone to instability of results. To address this issue, the paper introduces coefficient and variable stability index which help the practitioners to first investigate the issue and second, search for possible solutions. |

| Xia et al. (2020) | A Dynamic Credit Scoring Model Based on Survival Gradient Boosting Decision Tree Approach | Global | Data obtained from a consumer loan transactions of a major P2P lending platform in the U.S. | - | A "novel dynamic credit scoring model (i.e., SurvXGBoost) is proposed based on survival gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) approach." and "maintains some interpretability" by indicating feature importance. |

| Yuan et al. (2022) | An Empirical Study of the Effect of Bachground Data Size on the Stability of Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) for Deep Learning Models | Local & Global | MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database | Stability of SHAP with various background dataset sizes | Show that SHAP explanations fluctuate when using a small background sample size and that these fluctuations decrease when the background dataset sampling size increases. This finding holds true for both instance and model-level explanations. |

----------------------------------------------------------------------- Table 1: Literature Overview, Interpretability Methods.

This paper aims to answer the question whether it is possible to develop a model framework applicable within credit risk that achieves a high predictive performance as measured by the AUC whilst maintaining or even improving interpretability. A related question hence is whether there is a trade-off between performance (AUC) and interpretability.

Previous literature has highlighted the trade-off between simple, intrinsically interpretable models with limited accuracy and less transparent black-box models which exhibit a high predictive power. (Bussmann et al. 2021; Emad Azhar Ali et al. 2021) We expect that such a trade-off between interpretability and performance is also visible using our dataset when comparing a white-box model to a black-box model, as verbalized by hypotheses I and II.

I) The black-box model outperforms the white-box model (measured by the AUC).

II) The white-box model is better explainable than the black-box model.

We suspect that the trade-off formulated in hypotheses I and II can be relaxed by employing post-hoc methods, leading us to hypothesis III:

III) Through the usage of post-hoc methods, it is possible to achieve a higher performance compared to a white-box model (measured by the AUC) and having a higher degree of interpretability (compared to the black-box model) at the same time.

The analysis is performed using a credit risk dataset obtained from Freddie Mac (2021). Freddie Mac is a U.S. mortgage bank that was created by the United States Congress in 1970 to “ensure a reliable and affordable supply of mortgage funds throughout the country”. (Federal Housing Finance Agency 2022) Instead of lending to individuals directly, its business consists of purchasing loans on the secondary housing market, bundling them and selling them in the form of Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).(Freddie Mac 2022a) It separates its business operations into three major divisions: Single-Family Division, Multifamily Division and Capital Markets Division. The dataset used in this paper is the so-called Single Family Loan-Level Dataset (Origination Data File). As the name suggests it covers loans purchased by Freddie Mac’s Single-Family Division. (Freddie Mac 2021)

The dataset includes loans originated between 1999 and the Origination Cutoff Date.(Freddie Mac 2022c) The loans chosen for inclusion were selected at random from Freddie Mac’s loan portfolio and every loan had the same probability of inclusion. (Freddie Mac 2022b) Approximately 150.000 observations with the first payment date from 2013 to 2016 are used as training data to build the prediction models, while the test data consists of approximately 50.000 observations from 2017 to 2019.

In total, the dataset includes 31 features. These are described in the following table.

# Table of Features

file_name = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Group2Interpretability/\

APA_Interpretability/main/Input/columns_formatted.csv'

Feature_Table = pd.read_csv(file_name,index_col=False)

pd.set_option('display.max_colwidth', None)

Feature_Table = Feature_Table.drop('#', axis=1)

dfStyler = Feature_Table.style.set_properties(**{'text-align': 'left'})\

.hide_index()

display(dfStyler.set_table_styles([dict(selector='th',

props=[('text-align', 'left')])]))

print("-----------------------------------------------------------------------")

print("Table 2: Feature Description, taken from Freddie Mac (2022c)")

| Column name | Short description | Format | Long description | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fico | Credit Score | Numeric | CREDIT SCORE - A number, prepared by third parties, summarizing the borrowerÕs creditworthiness, which may be indicative of the likelihood that the borrower will timely repay future obligations. Generally, the credit score disclosed is the score known at the time of acquisition and is the score used to originate the mortgage. | 300 - 850 9999 = Not Available, if Credit Score is < 300 or > 850. |

| dt_first_pi | First Payment Date | Date | FIRST PAYMENT DATE - The date of the first scheduled mortgage payment due under the terms of the mortgage note. | YYYYMM |

| flag_fthb | First Time Homebuyer Flag | Alpha | FIRST TIME HOMEBUYER FLAG - Indicates whether the Borrower, or one of a group of Borrowers, is an individual who (1) is purchasing the mortgaged property, (2) will reside in the mortgaged property as a primary residence and (3) had no ownership interest (sole or joint) in a residential property during the three-year period preceding the date of the purchase of the mortgaged property. With certain limited exceptions, a displaced homemaker or single parent may also be considered a First-Time Homebuyer if the individual had no ownership interest in a residential property during the preceding three-year period other than an ownership interest in the marital residence with a spouse. | Y = Yes N = No 9 = Not Available or Not Applicable |

| dt_matr | Maturity Date | Date | MATURITY DATE - The month in which the final monthly payment on the mortgage is scheduled to be made as stated on the original mortgage note. | YYYYMM |

| cd_msa | Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) Or Metropolitan Division | Numeric | METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREA (MSA) OR METROPOLITAN DIVISION - This disclosure will be based on the designation of the Metropolitan Statistical Area or Metropolitan Division as of the date of issuance. Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) are defined by the United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and have at least one urbanized area with a population of 50,000 or more inhabitants. An MSA containing a single core with a population of 2.5 million or more may be divided into smaller groups of counties that OMB refers to as Metropolitan Divisions. If an MSA applies to a mortgaged property, the applicable five-digit value is disclosed; however, if the mortgaged property also falls within a Metropolitan Division classification, the applicable five-digit value for the Metropolitan Division takes precedence and is disclosed instead. This disclosure will not be updated to reflect any subsequent changes in designations of MSAs, Metropolitan Divisions or other classifications. Null indicates that the area in which the mortgaged property is located is (a) neither an MSA nor a Metropolitan Division, or (b) unknown. | Metropolitan Division or MSA Code. Space (5) = Indicates that the area in which the mortgaged property is located is a) neither an MSA nor a Metropolitan Division, or b) unknown. |

| mi_pct | Mortgage Insurance Percentage (MI %) | Numeric | MORTGAGE INSURANCE PERCENTAGE (MI %) - The percentage of loss coverage on the loan, at the time of Freddie Mac's purchase of the mortgage loan that a mortgage insurer is providing to cover losses incurred as a result of a default on the loan. Only primary mortgage insurance that is purchased by the Borrower, lender or Freddie Mac is disclosed. Mortgage insurance that constitutes "credit enhancement" that is not required by Freddie Mac's Charter is not disclosed. Amounts of mortgage insurance reported by Sellers that are less than 1% or greater than 55% will be disclosed as "Not Available," which will be indicated 999. No MI will be indicated by three zeros. | 1% - 55% 000 = No MI 999 = Not Available |

| cnt_units | Number of Units | Numeric | NUMBER OF UNITS - Denotes whether the mortgage is a one-, two-, three-, or four-unit property. | 1 = one-unit 2 = two-unit 3 = three-unit 4 = four-unit 99 = Not Available |

| occpy_sts | Occupancy Status | Alpha | OCCUPANCY STATUS - Denotes whether the mortgage type is owner occupied, second home, or investment property. | P = Primary Residence I = Investment Property S = Second Home 9 = Not Available |

| cltv | Original Combined Loan-to-Value (CLTV) | Numeric | ORIGINAL COMBINED LOAN-TO-VALUE (CLTV) - In the case of a purchase mortgage loan, the ratio is obtained by dividing the original mortgage loan amount on the note date plus any secondary mortgage loan amount disclosed by the Seller by the lesser of the mortgaged property's appraised value on the note date or its purchase price. In the case of a refinance mortgage loan, the ratio is obtained by dividing the original mortgage loan amount on the note date plus any secondary mortgage loan amount disclosed by the Seller by the mortgaged property's appraised value on the note date. If the secondary financing amount disclosed by the Seller includes a home equity line of credit, then the CLTV calculation reflects the disbursed amount at closing of the first lien mortgage loan, not the maximum loan amount available under the home equity line of credit. In the case of a seasoned mortgage loan, if the Seller cannot warrant that the value of the mortgaged property has not declined since the note date, Freddie Mac requires that the Seller must provide a new appraisal value, which is used in the CLTV calculation. In certain cases, where the Seller delivered a loan to Freddie Mac with a special code indicating additional secondary mortgage loan amounts, those amounts may have been included in the CLTV calculation. If the CLTV is LTV, set the CLTV to 'Not Available.' This disclosure is subject to the widely varying standards originators use to verify Borrowers' secondary mortgage loan amounts and will not be updated. | 201801 and prior: 6% - 200% 999 = Not Available 201802 and later: 1% - 998% 999 = Not Available HARP ranges: 1% - 998% 999 = Not Available |

| dti | Original Debt-to-Income (DTI) Ratio | Numeric | ORIGINAL DEBT-TO-INCOME (DTI) RATIO - Disclosure of the debt to income ratio is based on (1) the sum of the borrower's monthly debt payments, including monthly housing expenses that incorporate the mortgage payment the borrower is making at the time of the delivery of the mortgage loan to Freddie Mac, divided by (2) the total monthly income used to underwrite the loan as of the date of the origination of the such loan. Ratios greater than 65% are indicated that data is Not Available. All loans in the HARP dataset will be disclosed as Not Available. This disclosure is subject to the widely varying standards originators use to verify Borrowers' assets and liabilities and will not be updated. | 0% DTI =65% 999 = Not Available HARP ranges: 999 = Not Available |

| orig_upb | Original UPB | Numeric | ORIGINAL UPB - The UPB of the mortgage on the note date. | Amount will be rounded to the nearest $1,000. |

| ltv | Original Loan-to-Value (LTV) | Numeric | ORIGINAL LOAN-TO-VALUE (LTV) - In the case of a purchase mortgage loan, the ratio obtained by dividing the original mortgage loan amount on the note date by the lesser of the mortgaged property's appraised value on the note date or its purchase price. In the case of a refinance mortgage loan, the ratio obtained by dividing the original mortgage loan amount on the note date and the mortgaged property's appraised value on the note date. In the case of a seasoned mortgage loan, if the Seller cannot warrant that the value of the mortgaged property has not declined since the note date, Freddie Mac requires that the Seller must provide a new appraisal value, which is used in the LTV calculation. For loans in the non HARP dataset, ratios below 6% or greater than 105% will be disclosed as "Not Available," indicated by 999. For loans in the HARP dataset, LTV ratios greater than 999% will be disclosed as Not Available. | 201801 and prior: 6% - 105% 999 = Not Available 201802 and later: 1% - 998% 999 = Not Available HARP ranges: 1% - 998% 999 = Not Available |

| int_rt | Original Interest Rate | Numeric - 6,3 | ORIGINAL INTEREST RATE - The original note rate as indicated on the mortgage note. | nan |

| channel | Channel | Alpha | CHANNEL - Disclosure indicates whether a Broker or Correspondent, as those terms are defined below, originated or was involved in the origination of the mortgage loan. If a Third Party Origination is applicable, but the Seller does not specify Broker or Correspondent, the disclosure will indicate "TPO Not Specified". Similarly, if neither Third Party Origination nor Retail designations are available, the disclosure will indicate "TPO Not Specified." If a Broker, Correspondent or Third Party Origination disclosure is not applicable, the mortgage loan will be designated as Retail, as defined below. Broker is a person or entity that specializes in loan originations, receiving a commission (from a Correspondent or other lender) to match Borrowers and lenders. The Broker performs some or most of the loan processing functions, such as taking loan applications, or ordering credit reports, appraisals and title reports. Typically, the Broker does not underwrite or service the mortgage loan and generally does not use its own funds for closing; however, if the Broker funded a mortgage loan on a lender's behalf, such a mortgage loan is considered a "Broker" third party origination mortgage loan. The mortgage loan is generally closed in the name of the lender who commissioned the Broker's services. Correspondent is an entity that typically sells the Mortgages it originates to other lenders, which are not Affiliates of that entity, under a specific commitment or as part of an ongoing relationship. The Correspondent performs some, or all, of the loan processing functions, such as: taking the loan application; ordering credit reports, appraisals, and title reports; and verifying the Borrower's income and employment. The Correspondent may or may not have delegated underwriting and typically funds the mortgage loans at settlement. The mortgage loan is closed in the Correspondent's name and the Correspondent may or may not service the mortgage loan. The Correspondent may use a Broker to perform some of the processing functions or even to fund the loan on its behalf; under such circumstances, the mortgage loan is considered a "Broker" third party origination mortgage loan, rather than a "Correspondent" third party origination mortgage loan. Retail Mortgage is a mortgage loan that is originated, underwritten and funded by a lender or its Affiliates. The mortgage loan is closed in the name of the lender or its Affiliate and if it is sold to Freddie Mac, it is sold by the lender or its Affiliate that originated it. A mortgage loan that a Broker or Correspondent completely or partially originated, processed, underwrote, packaged, funded or closed is not considered a Retail mortgage loan. For purposes of the definitions of Correspondent and Retail, "Affiliate" means any entity that is related to another party as a consequence of the entity, directly or indirectly, controlling the other party, being controlled by the other party, or being under common control with the other party. | R = Retail B = Broker C = Correspondent T = TPO Not Specified 9 = Not Available |

| ppmt_pnlty | Prepayment Penalty Mortgage (PPM) Flag | Alpha | PREPAYMENT PENALTY MORTGAGE (PPM) FLAG - Denotes whether the mortgage is a PPM. A PPM is a mortgage with respect to which the borrower is, or at any time has been, obligated to pay a penalty in the event of certain repayments of principal. | Y = PPM N = Not PPM |

| prod_type | Amortization Type (Formerly Product Type) | Alpha | AMORTI ATION TYPE - Denotes that the product is a fixed-rate mortgage or adjustable-rate mortgage. | FRM - Fixed Rate Mortgage ARM - Adjustable Rate Mortgage |

| st | Property State | Alpha | PROPERTY STATE - A two-letter abbreviation indicating the state or territory within which the property securing the mortgage is located. | AL, T , VA, etc. |

| prop_type | Property Type | Alpha | PROPERTY TYPE - Denotes whether the property type secured by the mortgage is a condominium, leasehold, planned unit development (PUD), cooperative share, manufactured home, or Single-Family home. If the Property Type is Not Available, this will be indicated by 99. | CO = Condo PU = PUD MH = Manufactured Housing SF = Single-Family CP = Co-op 99 = Not Available |

| zipcode | Postal Code | Numeric | POSTAL CODE - The postal code for the location of the mortgaged property | 00, where " " represents the first three digits of the 5- digit postal code Space (5) = Unknown |

| id_loan | Loan Sequence Number | Numeric | LOAN SEQUENCE NUMBER - Unique identifier assigned to each loan. | nan |

| loan_purpose | Loan Purpose | Alpha | LOAN PURPOSE - Indicates whether the mortgage loan is a Cash- out Refinance mortgage, No Cash-out Refinance mortgage, or a Purchase mortgage. Generally, a Cash-out Refinance mortgage loan is a mortgage loan in which the use of the loan amount is not limited to specific purposes. A mortgage loan placed on a property previously owned free and clear by the Borrower is always considered a Cash-out Refinance mortgage loan. Generally, a No Cash-out Refinance mortgage loan is a mortgage loan in which the loan amount is limited to the following uses: Pay off the first mortgage, regardless of its age Pay off any junior liens secured by the mortgaged property, that were used in their entirety to acquire the subject property Pay related closing costs, financing costs and prepaid items, and Disburse cash out to the Borrower (or any other payee) not to exceed 2% of the new refinance mortgage loan or $2,000, whichever is less. As an exception to the above, for construction conversion mortgage loans and renovation mortgage loans, the amount of the interim construction financing secured by the mortgaged property is considered an amount used to pay off the first mortgage. Paying off unsecured liens or construction costs paid by the Borrower outside of the secured interim construction financing is considered cash out to the Borrower, if greater than $2000 or 2% of loan amount. This disclosure is subject to various special exceptions used by Sellers to determine whether a mortgage loan is a No Cash-out Refinance mortgage loan. | P = Purchase C = Refinance - Cash Out N = Refinance - No Cash Out R = Refinance - Not Specified 9 =Not Available |

| orig_loan_term | Original Loan Term | Numeric | ORIGINAL LOAN TERM - A calculation of the number of scheduled monthly payments of the mortgage based on the First Payment Date and Maturity Date. | Calculation: (Loan Maturity Date (MM/YY) - Loan First Payment Date (MM/YY) + 1) |

| cnt_borr | Number of Borrowers | Numeric | NUMBER OF BORROWERS - The number of Borrower(s) who are obligated to repay the mortgage note secured by the mortgaged property. Disclosure denotes only whether there is one borrower, or more than one borrower associated with the mortgage note. This disclosure will not be updated to reflect any subsequent assumption of the mortgage note. | 201801 and prior: 01 = 1 borrower 02 = > 1 borrowers 99 = Not Available 201802 and later: 01 = 1 borrower 02 = 2 borrowers 03 = 3 borrowers 09 = 9 borrowers 10 = 10 borrowers 99 = Not Available |

| seller_name | Seller Name | Alpha Numeric | SELLER NAME - The entity acting in its capacity as a seller of mortgages to Freddie Mac at the time of acquisition. Seller Name will be disclosed for sellers with a total Original UPB representing 1% or more of the total Original UPB of all loans in the Dataset for a given calendar quarter. Otherwise, the Seller Name will be set to "Other Sellers". | Name of the seller, or "Other Sellers" |

| servicer_name | Servicer Name | Alpha Numeric | SERVICER NAME - The entity acting in its capacity as the servicer of mortgages to Freddie Mac as of the last period for which loan activity is reported in the Dataset. Servicer Name will be disclosed for servicers with a total Original UPB representing 1% or more of the total Original UPB of all loans in the Dataset for a given calendar quarter. Otherwise, the Servicer Name will be set to "Other Servicers". | Name of the servicer, or "Other Servicers" |

| flag_sc | Super Conforming Flag | Alpha | SUPER CONFORMING FLAG - For mortgages that exceed conforming loan limits with origination dates on or after 10/1/2008 and were delivered to Freddie Mac on or after 1/1/2009 | Y = Yes Space (1) = Not Super Conforming |

| pre_relief | Pre-HARP Loan Sequence Number | Alpha Numeric - PYYQnXXXXXXX | PRE-RELIEF REFINANCE LOAN SEQUENCE NUMBER - The Loan Sequence Number link that associates a Relief Refinance loan to the Loan Sequence Number assigned to the loan from which it was refinanced within in the Single-Family Loan Level Dataset. Note: Populated only for loans where the Relief Refinance Indicator is set to Y. All other loans will be blank. | PYY0n Product F = FRM and A = ARM; YY0n = origination year and quarter; and, randomly assigned digits |

| pgrm_ind | Program Indicator | Alpha Numeric | PROGRAM INDICATOR - The indicator that identifies if a loan participates in and of the Freddie Mac programs listed in the valid values. Note: The standard dataset discloses these enumerations for loans originated on or after March 1, 2015. The Non-Standard dataset discloses enumerations for loans originated under the HP program between 1999 and February 28, 2015. Underwriting standards for Home Possible prior to March 1, 2015 may be different than the current standards. | H = Home Possible F = HFA Advantage 9 = Not Available or not part of Home Possible or HFA Advantage programs |

| rel_ref_ind | HARP Indicator | Alpha | RELIEF REFINANCE INDICATOR - Indicator that identifies whether the loan is part of Freddie Mac's Relief Refinance Program. Loans which are both a Relief Refinance and have an Original Loan-to-Value above 80 are HARP loans. | Y = Relief Refinance Loan Space = Non-Relief Refinance loan |

| prop_val_meth | Property Valuation Method | Numeric | PROPERTY VALUATION METHOD - The indicator denoting which method was used to obtain a property appraisal, if any. Note: Populated for loans originated on or after 1/1/2017. | 1 = ACE Loans 2 = Full Appraisal 3 = Other Appraisals (Desktop, driveby, external, AVM) 9 = Not Available |

| int_only_ind | Interest Only (I/O) Indicator | Alpha | INTEREST ONLY INDICATOR (I/O INDICATOR) - The indicator denoting whether the loan only requires interest payments for a specified period beginning with the first payment date. | Y = Yes N = No |

| TARGET | Default label | Numeric | Target label | 1 = Default, 0 otherwise |

----------------------------------------------------------------------- Table 2: Feature Description, taken from Freddie Mac (2022c)

The target feature, i.e. whether a loan defaulted or not defaulted, are not given in the original dataset. In constructing target values for the training dataset, the definition of default of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2004) was used:

“A default is considered to have occurred with regard to a particular obligor when […] [t]he obligor is past due more than 90 days on any material credit obligation to the banking group.[…] Overdrafts will be considered as being past due once the customer has breached an advised limit or been advised of a limit smaller than current outstandings.“

Using this definition, the overall default ratio (defaulted loans over non defaulted loans) is given by 0.009103, i.e. approximately 0.9%. In the following, summary statistics are presented for numerical features. In addition to mean and standard deviation, the mean difference (mean of non-defaulted loans – mean of defaulted loans) is calculated. Features, for which the mean difference is negative (positive), are highlighted in red (green).

Categorical features, on the other hand, are treated one-by-one. For each category of a feature, the absolute and relative frequency in the test and training dataset is indicated. Then, for the training dataset, the proportion of defaulted and non-defaulted loans within each category is reported (for the test dataset, this is not possible, as no target values are available). Finally, the ratio of defaulted and non-defaulted loans within each category is calculated and the differences to the overall default ratio are calculated. Negative differences are highlighted in green, positive differences in red. In this way, the reader is given a quick overview of the data and can identify potential correlations between feature characteristics and the target.

As an example, consider the feature ‘servicer_name’. Here, for ‘servicer_name == SPECIALIZED LOAN SERVICING LLC’, the default ratio is equal to approximately 15.2% and thus 16.7 times higher than the average default ratio. This is on example of an interesting prima facie evidence that becomes visible through this preliminary analysis.

For further information regarding the data collection and the characteristics of the dataset, the interested reader is referred to the data provider Freddie Mac (2021).

# import train data

file_train = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Group2Interpretability/\

APA_Interpretability/main/Input/data_train.csv'

df_train = pd.read_csv(file_train,index_col=False)

# import test data

file_test = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Group2Interpretability/\

APA_Interpretability/main/Input/data_test.csv'

df_test = pd.read_csv(file_test,index_col=False)

Columns (27) have mixed types.Specify dtype option on import or set low_memory=False.

# Overall Ratio Defaults/Non-Defaults as Benchmark for further analysis

# Calculate overall ratio defaults/non-defaults as benchmark

ratio_overall = df_train.groupby(by=["TARGET"])["TARGET"].count()[1]\

/df_train.groupby(by=["TARGET"])["TARGET"].count()[0]

print("Overall ratio of defaults/non-defaults: %0.6f" %ratio_overall)

Overall ratio of defaults/non-defaults: 0.009103

# Define all numerical features

numerical_cols = ['fico', 'mi_pct', 'cnt_units', 'cltv', 'dti', 'orig_upb',

'ltv', 'int_rt', 'orig_loan_term', 'cnt_borr']

# Calculate mean grouped by the target feature

df_diff = df_train.groupby(["TARGET"])[numerical_cols].mean()

df_diff=pd.concat((df_diff,df_diff.diff(periods=len(df_diff)-1).dropna()))

df_diff = df_diff.reset_index(drop = True)

df_diff.index = ('Mean_Non_Default', 'Mean_Default', 'Difference_in_Mean')

# Calculate std grouped by the target feature

df_std = df_train.groupby(["TARGET"])[numerical_cols].std()

df_std.index = ('Std_Non_Default', 'Std_Default')

# Calculate the differences in mean and std of defaulting and non-defaulting

df_diff = pd.concat([df_diff, df_std] )

df_diff = df_diff.reindex(['Mean_Non_Default', 'Std_Non_Default',

'Mean_Default', 'Std_Default', 'Difference_in_Mean'])

# Color the results depending on output

# Subset dataframe with condition to color the different results

test = df_diff[df_diff.index=='Difference_in_Mean']

# Pass the subset dataframe index and column to pd.IndexSlice

slice_ = pd.IndexSlice[test.index, test.columns]

# Color the results

df_diff.style.applymap(lambda v: 'color:green;' if (v > 0) else None,

subset = slice_)\

.applymap(lambda v: 'color:red;' if (v <= 0) else None,

subset = slice_)\

.format(precision=0, na_rep='Missings', thousands=" ",

formatter={('fico'): "{:.2f}",

('mi_pct'): "{:.2f}",

('cnt_units'): "{:.2f}",

('cltv'): "{:.2f}",

('ltv'): "{:.2f}",

('int_rt'): "{:.2f}",

('orig_loan_term'): "{:.2f}",

('cnt_borr'): "{:.2f}"

})

| fico | mi_pct | cnt_units | cltv | dti | orig_upb | ltv | int_rt | orig_loan_term | cnt_borr | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean_Non_Default | 749.72 | 5.53 | 1.03 | 76.09 | 200 | 211 534 | 74.67 | 4.07 | 310.54 | 1.52 |

| Std_Non_Default | 90.39 | 10.94 | 0.24 | 21.61 | 365 | 116 687 | 20.93 | 0.55 | 79.11 | 0.50 |

| Mean_Default | 695.84 | 8.14 | 1.02 | 90.06 | 441 | 187 629 | 86.26 | 4.40 | 330.08 | 1.31 |

| Std_Default | 61.28 | 12.52 | 0.19 | 31.63 | 475 | 105 417 | 27.99 | 0.50 | 64.21 | 0.46 |

| Difference_in_Mean | -53.88 | 2.62 | -0.01 | 13.97 | 241 | -23 905 | 11.59 | 0.33 | 19.54 | -0.21 |

# cd_msa

# create table from train data

df_vis_train = df_train.groupby("cd_msa")["TARGET"]\

.value_counts(normalize=True).unstack()

df_vis_train = df_vis_train.fillna(0)

df_vis_train["Count_Train"] = df_train.groupby(['cd_msa']).size()

df_vis_train['Ratio_Cat_Train'] = df_vis_train.Count_Train / df_train.shape[0]

df_vis_train["Ratio_default/nondefault"] = df_vis_train[1]/df_vis_train[0]

# calculate difference to overall ratio

df_vis_train["Difference_Overall"] = df_vis_train["Ratio_default/nondefault"] \

- ratio_overall

df_vis_train = df_vis_train.sort_values(by=['Ratio_default/nondefault'],

ascending=False)

df_vis_train = df_vis_train.rename(columns={0: 'Ratio_NonDefault',

1: 'Ratio_Default'})

# create table from test data

# calculate number of observation in each category

Count = df_test.groupby(['cd_msa']).size()

df_vis_test = pd.DataFrame(data = Count, columns=['Count_Test'])

df_vis_test['Ratio_Cat_Test'] = df_vis_test.Count_Test / df_train.shape[0]

# full outer join both tables

df_join1 = df_vis_train.reset_index()

df_join2 = df_vis_test.reset_index()

# change order and index names

df_cd_msa = pd.merge(df_join1,df_join2 ,on='cd_msa',how='outer')

df_cd_msa = df_cd_msa.set_index("cd_msa")

df_cd_msa = df_cd_msa[['Count_Train', 'Ratio_Cat_Train', 'Count_Test',

'Ratio_Cat_Test', 'Ratio_NonDefault', 'Ratio_Default',

'Ratio_default/nondefault', 'Difference_Overall']]

# do some color changing

subset = ['Difference_Overall']

df_cd_msa.style.applymap(lambda v: 'color:red;' if (v > 0) else None,

subset = subset)\

.applymap(lambda v: 'color:green;' if (v <= 0) else None,

subset = subset)\

.applymap(lambda x: 'color: blue' if pd.isna(x) else '')\

.format(precision=0, na_rep='Missings', thousands=" ",

formatter={('Count_Train'): "{:.0f}",

('Ratio_Cat_Train'): "{:.5f}",

('Count_Test'): "{:.0f}",

('Ratio_Cat_Test'): "{:.5f}",

('Ratio_NonDefault'): "{:.5f}",

('Ratio_Default'): "{:.5f}",

('Ratio_default/nondefault'): "{:.5f}",

('Difference_Overall'): "{:.5f}"

})

| Count_Train | Ratio_Cat_Train | Count_Test | Ratio_Cat_Test | Ratio_NonDefault | Ratio_Default | Ratio_default/nondefault | Difference_Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cd_msa | ||||||||

| 37380.0 | 13 | 0.00009 | 1 | 0.00001 | 0.92308 | 0.07692 | 0.08333 | 0.07423 |

| 24500.0 | 30 | 0.00020 | 6 | 0.00004 | 0.93333 | 0.06667 | 0.07143 | 0.06233 |

| 46660.0 | 45 | 0.00030 | 10 | 0.00007 | 0.93333 | 0.06667 | 0.07143 | 0.06233 |

| 47020.0 | 18 | 0.00012 | 4 | 0.00003 | 0.94444 | 0.05556 | 0.05882 | 0.04972 |

| 17420.0 | 44 | 0.00029 | 23 | 0.00015 | 0.95455 | 0.04545 | 0.04762 | 0.03852 |

| 15260.0 | 44 | 0.00029 | 11 | 0.00007 | 0.95455 | 0.04545 | 0.04762 | 0.03852 |

| 12100.0 | 93 | 0.00062 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.95699 | 0.04301 | 0.04494 | 0.03584 |

| 24220.0 | 48 | 0.00032 | 19 | 0.00013 | 0.95833 | 0.04167 | 0.04348 | 0.03438 |

| 13020.0 | 24 | 0.00016 | 8 | 0.00005 | 0.95833 | 0.04167 | 0.04348 | 0.03438 |

| 41660.0 | 25 | 0.00017 | 8 | 0.00005 | 0.96000 | 0.04000 | 0.04167 | 0.03256 |

| 17980.0 | 77 | 0.00051 | 21 | 0.00014 | 0.96104 | 0.03896 | 0.04054 | 0.03144 |

| 28100.0 | 77 | 0.00051 | 27 | 0.00018 | 0.96104 | 0.03896 | 0.04054 | 0.03144 |

| 29340.0 | 52 | 0.00035 | 22 | 0.00015 | 0.96154 | 0.03846 | 0.04000 | 0.03090 |

| 47380.0 | 53 | 0.00035 | 25 | 0.00017 | 0.96226 | 0.03774 | 0.03922 | 0.03011 |

| 33124.0 | 691 | 0.00461 | 287 | 0.00191 | 0.96237 | 0.03763 | 0.03910 | 0.02999 |

| 20764.0 | 133 | 0.00089 | 13 | 0.00009 | 0.96241 | 0.03759 | 0.03906 | 0.02996 |

| 12940.0 | 275 | 0.00183 | 89 | 0.00059 | 0.96364 | 0.03636 | 0.03774 | 0.02863 |

| 16620.0 | 56 | 0.00037 | 16 | 0.00011 | 0.96429 | 0.03571 | 0.03704 | 0.02793 |

| 25220.0 | 28 | 0.00019 | 10 | 0.00007 | 0.96429 | 0.03571 | 0.03704 | 0.02793 |

| 43340.0 | 85 | 0.00057 | 30 | 0.00020 | 0.96471 | 0.03529 | 0.03659 | 0.02748 |

| 16300.0 | 116 | 0.00077 | 30 | 0.00020 | 0.96552 | 0.03448 | 0.03571 | 0.02661 |

| 13140.0 | 92 | 0.00061 | 33 | 0.00022 | 0.96739 | 0.03261 | 0.03371 | 0.02460 |

| 19140.0 | 31 | 0.00021 | 7 | 0.00005 | 0.96774 | 0.03226 | 0.03333 | 0.02423 |

| 43580.0 | 63 | 0.00042 | 12 | 0.00008 | 0.96825 | 0.03175 | 0.03279 | 0.02368 |

| 37764.0 | 32 | 0.00021 | 5 | 0.00003 | 0.96875 | 0.03125 | 0.03226 | 0.02316 |

| 40580.0 | 32 | 0.00021 | 11 | 0.00007 | 0.96875 | 0.03125 | 0.03226 | 0.02316 |

| 26300.0 | 32 | 0.00021 | 14 | 0.00009 | 0.96875 | 0.03125 | 0.03226 | 0.02316 |

| 22744.0 | 818 | 0.00545 | 322 | 0.00215 | 0.96944 | 0.03056 | 0.03153 | 0.02242 |

| 36100.0 | 137 | 0.00091 | 53 | 0.00035 | 0.97080 | 0.02920 | 0.03008 | 0.02097 |

| 33740.0 | 35 | 0.00023 | 13 | 0.00009 | 0.97143 | 0.02857 | 0.02941 | 0.02031 |

| 15804.0 | 432 | 0.00288 | 172 | 0.00115 | 0.97222 | 0.02778 | 0.02857 | 0.01947 |

| 21060.0 | 36 | 0.00024 | 9 | 0.00006 | 0.97222 | 0.02778 | 0.02857 | 0.01947 |

| 18880.0 | 108 | 0.00072 | 35 | 0.00023 | 0.97222 | 0.02778 | 0.02857 | 0.01947 |

| 13644.0 | 108 | 0.00072 | 5 | 0.00003 | 0.97222 | 0.02778 | 0.02857 | 0.01947 |

| 10500.0 | 37 | 0.00025 | 8 | 0.00005 | 0.97297 | 0.02703 | 0.02778 | 0.01867 |

| 16180.0 | 37 | 0.00025 | 16 | 0.00011 | 0.97297 | 0.02703 | 0.02778 | 0.01867 |

| 16020.0 | 38 | 0.00025 | 17 | 0.00011 | 0.97368 | 0.02632 | 0.02703 | 0.01792 |

| 29180.0 | 115 | 0.00077 | 28 | 0.00019 | 0.97391 | 0.02609 | 0.02679 | 0.01768 |

| 36740.0 | 1043 | 0.00695 | 415 | 0.00277 | 0.97411 | 0.02589 | 0.02657 | 0.01747 |

| 48900.0 | 232 | 0.00155 | 68 | 0.00045 | 0.97414 | 0.02586 | 0.02655 | 0.01745 |

| 16940.0 | 39 | 0.00026 | 18 | 0.00012 | 0.97436 | 0.02564 | 0.02632 | 0.01721 |

| 30140.0 | 40 | 0.00027 | 13 | 0.00009 | 0.97500 | 0.02500 | 0.02564 | 0.01654 |

| 45540.0 | 41 | 0.00027 | 8 | 0.00005 | 0.97561 | 0.02439 | 0.02500 | 0.01590 |

| 23580.0 | 82 | 0.00055 | 38 | 0.00025 | 0.97561 | 0.02439 | 0.02500 | 0.01590 |

| 20020.0 | 41 | 0.00027 | 2 | 0.00001 | 0.97561 | 0.02439 | 0.02500 | 0.01590 |

| 26180.0 | 42 | 0.00028 | 4 | 0.00003 | 0.97619 | 0.02381 | 0.02439 | 0.01529 |

| 26140.0 | 42 | 0.00028 | 18 | 0.00012 | 0.97619 | 0.02381 | 0.02439 | 0.01529 |

| 46140.0 | 295 | 0.00197 | 112 | 0.00075 | 0.97627 | 0.02373 | 0.02431 | 0.01520 |

| 42680.0 | 85 | 0.00057 | 28 | 0.00019 | 0.97647 | 0.02353 | 0.02410 | 0.01499 |

| 13980.0 | 85 | 0.00057 | 11 | 0.00007 | 0.97647 | 0.02353 | 0.02410 | 0.01499 |

| 32900.0 | 87 | 0.00058 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.97701 | 0.02299 | 0.02353 | 0.01443 |

| 22420.0 | 131 | 0.00087 | 44 | 0.00029 | 0.97710 | 0.02290 | 0.02344 | 0.01433 |

| 20700.0 | 44 | 0.00029 | 23 | 0.00015 | 0.97727 | 0.02273 | 0.02326 | 0.01415 |

| 12540.0 | 309 | 0.00206 | 136 | 0.00091 | 0.97735 | 0.02265 | 0.02318 | 0.01408 |

| 18020.0 | 45 | 0.00030 | 9 | 0.00006 | 0.97778 | 0.02222 | 0.02273 | 0.01362 |

| 47644.0 | 364 | 0.00243 | 19 | 0.00013 | 0.97802 | 0.02198 | 0.02247 | 0.01337 |

| 34580.0 | 46 | 0.00031 | 25 | 0.00017 | 0.97826 | 0.02174 | 0.02222 | 0.01312 |

| 34940.0 | 187 | 0.00125 | 73 | 0.00049 | 0.97861 | 0.02139 | 0.02186 | 0.01275 |

| 49740.0 | 47 | 0.00031 | 15 | 0.00010 | 0.97872 | 0.02128 | 0.02174 | 0.01264 |

| 31420.0 | 47 | 0.00031 | 17 | 0.00011 | 0.97872 | 0.02128 | 0.02174 | 0.01264 |

| 35100.0 | 47 | 0.00031 | 13 | 0.00009 | 0.97872 | 0.02128 | 0.02174 | 0.01264 |

| 31460.0 | 47 | 0.00031 | 29 | 0.00019 | 0.97872 | 0.02128 | 0.02174 | 0.01264 |

| 45780.0 | 287 | 0.00191 | 101 | 0.00067 | 0.97909 | 0.02091 | 0.02135 | 0.01225 |

| 45060.0 | 144 | 0.00096 | 46 | 0.00031 | 0.97917 | 0.02083 | 0.02128 | 0.01217 |

| 49340.0 | 436 | 0.00291 | 163 | 0.00109 | 0.97936 | 0.02064 | 0.02108 | 0.01197 |

| 27260.0 | 584 | 0.00389 | 216 | 0.00144 | 0.97945 | 0.02055 | 0.02098 | 0.01188 |

| 27900.0 | 49 | 0.00033 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.97959 | 0.02041 | 0.02083 | 0.01173 |

| 11100.0 | 50 | 0.00033 | 17 | 0.00011 | 0.98000 | 0.02000 | 0.02041 | 0.01131 |

| 29460.0 | 252 | 0.00168 | 97 | 0.00065 | 0.98016 | 0.01984 | 0.02024 | 0.01114 |

| 33660.0 | 101 | 0.00067 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.98020 | 0.01980 | 0.02020 | 0.01110 |

| 46340.0 | 52 | 0.00035 | 23 | 0.00015 | 0.98077 | 0.01923 | 0.01961 | 0.01050 |

| 39460.0 | 106 | 0.00071 | 49 | 0.00033 | 0.98113 | 0.01887 | 0.01923 | 0.01013 |

| 29740.0 | 53 | 0.00035 | 17 | 0.00011 | 0.98113 | 0.01887 | 0.01923 | 0.01013 |

| 43780.0 | 110 | 0.00073 | 43 | 0.00029 | 0.98182 | 0.01818 | 0.01852 | 0.00942 |

| 47940.0 | 55 | 0.00037 | 10 | 0.00007 | 0.98182 | 0.01818 | 0.01852 | 0.00942 |

| 39380.0 | 55 | 0.00037 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.98182 | 0.01818 | 0.01852 | 0.00942 |

| 45300.0 | 1327 | 0.00885 | 529 | 0.00353 | 0.98191 | 0.01809 | 0.01842 | 0.00932 |

| 29420.0 | 113 | 0.00075 | 52 | 0.00035 | 0.98230 | 0.01770 | 0.01802 | 0.00891 |

| 39660.0 | 58 | 0.00039 | 12 | 0.00008 | 0.98276 | 0.01724 | 0.01754 | 0.00844 |

| 45940.0 | 117 | 0.00078 | 34 | 0.00023 | 0.98291 | 0.01709 | 0.01739 | 0.00829 |

| 21340.0 | 118 | 0.00079 | 33 | 0.00022 | 0.98305 | 0.01695 | 0.01724 | 0.00814 |

| 39820.0 | 118 | 0.00079 | 43 | 0.00029 | 0.98305 | 0.01695 | 0.01724 | 0.00814 |

| 29620.0 | 241 | 0.00161 | 72 | 0.00048 | 0.98340 | 0.01660 | 0.01688 | 0.00777 |

| 12220.0 | 61 | 0.00041 | 32 | 0.00021 | 0.98361 | 0.01639 | 0.01667 | 0.00756 |

| 44140.0 | 183 | 0.00122 | 58 | 0.00039 | 0.98361 | 0.01639 | 0.01667 | 0.00756 |

| 37964.0 | 682 | 0.00455 | 197 | 0.00131 | 0.98387 | 0.01613 | 0.01639 | 0.00729 |

| 31340.0 | 125 | 0.00083 | 33 | 0.00022 | 0.98400 | 0.01600 | 0.01626 | 0.00716 |

| 25420.0 | 252 | 0.00168 | 73 | 0.00049 | 0.98413 | 0.01587 | 0.01613 | 0.00703 |

| 17020.0 | 127 | 0.00085 | 59 | 0.00039 | 0.98425 | 0.01575 | 0.01600 | 0.00690 |

| 15680.0 | 64 | 0.00043 | 11 | 0.00007 | 0.98438 | 0.01562 | 0.01587 | 0.00677 |

| 26420.0 | 2835 | 0.01890 | 960 | 0.00640 | 0.98483 | 0.01517 | 0.01540 | 0.00630 |

| 44100.0 | 66 | 0.00044 | 24 | 0.00016 | 0.98485 | 0.01515 | 0.01538 | 0.00628 |

| 15940.0 | 133 | 0.00089 | 41 | 0.00027 | 0.98496 | 0.01504 | 0.01527 | 0.00616 |

| 29200.0 | 67 | 0.00045 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.98507 | 0.01493 | 0.01515 | 0.00605 |

| 20100.0 | 67 | 0.00045 | 22 | 0.00015 | 0.98507 | 0.01493 | 0.01515 | 0.00605 |

| 11700.0 | 201 | 0.00134 | 79 | 0.00053 | 0.98507 | 0.01493 | 0.01515 | 0.00605 |

| 35840.0 | 474 | 0.00316 | 202 | 0.00135 | 0.98523 | 0.01477 | 0.01499 | 0.00589 |

| 47300.0 | 136 | 0.00091 | 59 | 0.00039 | 0.98529 | 0.01471 | 0.01493 | 0.00582 |

| 23844.0 | 342 | 0.00228 | 131 | 0.00087 | 0.98538 | 0.01462 | 0.01484 | 0.00573 |

| 25060.0 | 69 | 0.00046 | 29 | 0.00019 | 0.98551 | 0.01449 | 0.01471 | 0.00560 |

| 14740.0 | 139 | 0.00093 | 65 | 0.00043 | 0.98561 | 0.01439 | 0.01460 | 0.00550 |

| 48424.0 | 699 | 0.00466 | 295 | 0.00197 | 0.98569 | 0.01431 | 0.01451 | 0.00541 |

| 36420.0 | 423 | 0.00282 | 174 | 0.00116 | 0.98582 | 0.01418 | 0.01439 | 0.00529 |

| 28700.0 | 71 | 0.00047 | 20 | 0.00013 | 0.98592 | 0.01408 | 0.01429 | 0.00518 |

| 26620.0 | 213 | 0.00142 | 69 | 0.00046 | 0.98592 | 0.01408 | 0.01429 | 0.00518 |

| 35380.0 | 429 | 0.00286 | 132 | 0.00088 | 0.98601 | 0.01399 | 0.01418 | 0.00508 |

| 15500.0 | 72 | 0.00048 | 24 | 0.00016 | 0.98611 | 0.01389 | 0.01408 | 0.00498 |

| 42540.0 | 145 | 0.00097 | 24 | 0.00016 | 0.98621 | 0.01379 | 0.01399 | 0.00488 |

| 34820.0 | 363 | 0.00242 | 114 | 0.00076 | 0.98623 | 0.01377 | 0.01397 | 0.00486 |

| 24540.0 | 218 | 0.00145 | 106 | 0.00071 | 0.98624 | 0.01376 | 0.01395 | 0.00485 |

| 17460.0 | 728 | 0.00485 | 247 | 0.00165 | 0.98626 | 0.01374 | 0.01393 | 0.00482 |

| 20994.0 | 366 | 0.00244 | 195 | 0.00130 | 0.98634 | 0.01366 | 0.01385 | 0.00475 |

| 10420.0 | 297 | 0.00198 | 119 | 0.00079 | 0.98653 | 0.01347 | 0.01365 | 0.00455 |

| 19380.0 | 149 | 0.00099 | 11 | 0.00007 | 0.98658 | 0.01342 | 0.01361 | 0.00450 |

| 16974.0 | 2181 | 0.01454 | 166 | 0.00111 | 0.98670 | 0.01330 | 0.01348 | 0.00437 |

| 27140.0 | 154 | 0.00103 | 42 | 0.00028 | 0.98701 | 0.01299 | 0.01316 | 0.00405 |

| 19300.0 | 78 | 0.00052 | 38 | 0.00025 | 0.98718 | 0.01282 | 0.01299 | 0.00388 |

| 34740.0 | 78 | 0.00052 | 35 | 0.00023 | 0.98718 | 0.01282 | 0.01299 | 0.00388 |

| 39740.0 | 158 | 0.00105 | 41 | 0.00027 | 0.98734 | 0.01266 | 0.01282 | 0.00372 |

| 28940.0 | 316 | 0.00211 | 115 | 0.00077 | 0.98734 | 0.01266 | 0.01282 | 0.00372 |

| 22220.0 | 237 | 0.00158 | 95 | 0.00063 | 0.98734 | 0.01266 | 0.01282 | 0.00372 |

| 38860.0 | 323 | 0.00215 | 83 | 0.00055 | 0.98762 | 0.01238 | 0.01254 | 0.00344 |

| 33780.0 | 81 | 0.00054 | 21 | 0.00014 | 0.98765 | 0.01235 | 0.01250 | 0.00340 |

| 29940.0 | 82 | 0.00055 | 22 | 0.00015 | 0.98780 | 0.01220 | 0.01235 | 0.00324 |

| 14484.0 | 83 | 0.00055 | 5 | 0.00003 | 0.98795 | 0.01205 | 0.01220 | 0.00309 |

| 37460.0 | 85 | 0.00057 | 25 | 0.00017 | 0.98824 | 0.01176 | 0.01190 | 0.00280 |

| 46220.0 | 86 | 0.00057 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.98837 | 0.01163 | 0.01176 | 0.00266 |

| 36540.0 | 351 | 0.00234 | 128 | 0.00085 | 0.98860 | 0.01140 | 0.01153 | 0.00242 |

| 39300.0 | 705 | 0.00470 | 224 | 0.00149 | 0.98865 | 0.01135 | 0.01148 | 0.00237 |

| 23420.0 | 356 | 0.00237 | 146 | 0.00097 | 0.98876 | 0.01124 | 0.01136 | 0.00226 |

| 24300.0 | 89 | 0.00059 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.98876 | 0.01124 | 0.01136 | 0.00226 |

| 49700.0 | 89 | 0.00059 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.98876 | 0.01124 | 0.01136 | 0.00226 |

| 39100.0 | 180 | 0.00120 | 107 | 0.00071 | 0.98889 | 0.01111 | 0.01124 | 0.00213 |

| 35980.0 | 90 | 0.00060 | 23 | 0.00015 | 0.98889 | 0.01111 | 0.01124 | 0.00213 |

| 20260.0 | 180 | 0.00120 | 64 | 0.00043 | 0.98889 | 0.01111 | 0.01124 | 0.00213 |

| 31140.0 | 632 | 0.00421 | 220 | 0.00147 | 0.98892 | 0.01108 | 0.01120 | 0.00210 |

| 10900.0 | 364 | 0.00243 | 102 | 0.00068 | 0.98901 | 0.01099 | 0.01111 | 0.00201 |

| 21140.0 | 92 | 0.00061 | 26 | 0.00017 | 0.98913 | 0.01087 | 0.01099 | 0.00189 |

| 36260.0 | 372 | 0.00248 | 168 | 0.00112 | 0.98925 | 0.01075 | 0.01087 | 0.00177 |

| 15980.0 | 373 | 0.00249 | 156 | 0.00104 | 0.98928 | 0.01072 | 0.01084 | 0.00174 |

| 35300.0 | 379 | 0.00253 | 101 | 0.00067 | 0.98945 | 0.01055 | 0.01067 | 0.00156 |

| 41620.0 | 772 | 0.00515 | 339 | 0.00226 | 0.98964 | 0.01036 | 0.01047 | 0.00137 |

| 33700.0 | 293 | 0.00195 | 120 | 0.00080 | 0.98976 | 0.01024 | 0.01034 | 0.00124 |

| 11540.0 | 98 | 0.00065 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.98980 | 0.01020 | 0.01031 | 0.00121 |

| 12020.0 | 100 | 0.00067 | 32 | 0.00021 | 0.99000 | 0.01000 | 0.01010 | 0.00100 |

| 16700.0 | 406 | 0.00271 | 158 | 0.00105 | 0.99015 | 0.00985 | 0.00995 | 0.00085 |

| 11260.0 | 203 | 0.00135 | 55 | 0.00037 | 0.99015 | 0.00985 | 0.00995 | 0.00085 |

| 46520.0 | 317 | 0.00211 | 115 | 0.00077 | 0.99054 | 0.00946 | 0.00955 | 0.00045 |

| 40060.0 | 637 | 0.00425 | 202 | 0.00135 | 0.99058 | 0.00942 | 0.00951 | 0.00041 |

| 48864.0 | 319 | 0.00213 | 99 | 0.00066 | 0.99060 | 0.00940 | 0.00949 | 0.00039 |

| 14010.0 | 107 | 0.00071 | 38 | 0.00025 | 0.99065 | 0.00935 | 0.00943 | 0.00033 |

| 33860.0 | 107 | 0.00071 | 30 | 0.00020 | 0.99065 | 0.00935 | 0.00943 | 0.00033 |

| 47260.0 | 654 | 0.00436 | 171 | 0.00114 | 0.99083 | 0.00917 | 0.00926 | 0.00016 |

| 41700.0 | 654 | 0.00436 | 253 | 0.00169 | 0.99083 | 0.00917 | 0.00926 | 0.00016 |

| 17140.0 | 1428 | 0.00952 | 429 | 0.00286 | 0.99090 | 0.00910 | 0.00919 | 0.00008 |

| 23104.0 | 1001 | 0.00667 | 454 | 0.00303 | 0.99101 | 0.00899 | 0.00907 | -0.00003 |

| 13740.0 | 112 | 0.00075 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.99107 | 0.00893 | 0.00901 | -0.00009 |

| 43620.0 | 113 | 0.00075 | 44 | 0.00029 | 0.99115 | 0.00885 | 0.00893 | -0.00017 |

| 33340.0 | 792 | 0.00528 | 265 | 0.00177 | 0.99116 | 0.00884 | 0.00892 | -0.00019 |

| 10740.0 | 340 | 0.00227 | 95 | 0.00063 | 0.99118 | 0.00882 | 0.00890 | -0.00020 |

| 39540.0 | 114 | 0.00076 | 40 | 0.00027 | 0.99123 | 0.00877 | 0.00885 | -0.00025 |

| 45820.0 | 114 | 0.00076 | 50 | 0.00033 | 0.99123 | 0.00877 | 0.00885 | -0.00025 |

| 40380.0 | 459 | 0.00306 | 147 | 0.00098 | 0.99129 | 0.00871 | 0.00879 | -0.00031 |

| 12060.0 | 2894 | 0.01930 | 1040 | 0.00693 | 0.99136 | 0.00864 | 0.00871 | -0.00039 |

| 17780.0 | 116 | 0.00077 | 34 | 0.00023 | 0.99138 | 0.00862 | 0.00870 | -0.00041 |

| 16860.0 | 234 | 0.00156 | 90 | 0.00060 | 0.99145 | 0.00855 | 0.00862 | -0.00048 |

| 13820.0 | 471 | 0.00314 | 144 | 0.00096 | 0.99151 | 0.00849 | 0.00857 | -0.00054 |

| 44180.0 | 237 | 0.00158 | 77 | 0.00051 | 0.99156 | 0.00844 | 0.00851 | -0.00059 |

| 29820.0 | 1079 | 0.00719 | 442 | 0.00295 | 0.99166 | 0.00834 | 0.00841 | -0.00069 |

| 17660.0 | 120 | 0.00080 | 47 | 0.00031 | 0.99167 | 0.00833 | 0.00840 | -0.00070 |

| 35004.0 | 1085 | 0.00723 | 332 | 0.00221 | 0.99171 | 0.00829 | 0.00836 | -0.00074 |

| 25860.0 | 121 | 0.00081 | 40 | 0.00027 | 0.99174 | 0.00826 | 0.00833 | -0.00077 |

| 49180.0 | 247 | 0.00165 | 82 | 0.00055 | 0.99190 | 0.00810 | 0.00816 | -0.00094 |

| 17860.0 | 124 | 0.00083 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.99194 | 0.00806 | 0.00813 | -0.00097 |

| 23540.0 | 125 | 0.00083 | 33 | 0.00022 | 0.99200 | 0.00800 | 0.00806 | -0.00104 |

| 24860.0 | 376 | 0.00251 | 137 | 0.00091 | 0.99202 | 0.00798 | 0.00804 | -0.00106 |

| 48620.0 | 253 | 0.00169 | 68 | 0.00045 | 0.99209 | 0.00791 | 0.00797 | -0.00113 |

| 31700.0 | 255 | 0.00170 | 70 | 0.00047 | 0.99216 | 0.00784 | 0.00791 | -0.00120 |

| 43524.0 | 273 | 0.00182 | 13 | 0.00009 | 0.99267 | 0.00733 | 0.00738 | -0.00172 |

| 37860.0 | 138 | 0.00092 | 52 | 0.00035 | 0.99275 | 0.00725 | 0.00730 | -0.00180 |

| 38060.0 | 2773 | 0.01849 | 1132 | 0.00755 | 0.99279 | 0.00721 | 0.00726 | -0.00184 |

| 12580.0 | 1423 | 0.00949 | 394 | 0.00263 | 0.99297 | 0.00703 | 0.00708 | -0.00203 |

| 42034.0 | 144 | 0.00096 | 30 | 0.00020 | 0.99306 | 0.00694 | 0.00699 | -0.00211 |

| 40220.0 | 145 | 0.00097 | 42 | 0.00028 | 0.99310 | 0.00690 | 0.00694 | -0.00216 |

| 37100.0 | 583 | 0.00389 | 142 | 0.00095 | 0.99314 | 0.00686 | 0.00691 | -0.00219 |

| 37340.0 | 298 | 0.00199 | 125 | 0.00083 | 0.99329 | 0.00671 | 0.00676 | -0.00235 |

| 16984.0 | 2092 | 0.01395 | 1340 | 0.00893 | 0.99331 | 0.00669 | 0.00674 | -0.00237 |

| 19340.0 | 151 | 0.00101 | 36 | 0.00024 | 0.99338 | 0.00662 | 0.00667 | -0.00244 |

| 30780.0 | 311 | 0.00207 | 116 | 0.00077 | 0.99357 | 0.00643 | 0.00647 | -0.00263 |

| 19124.0 | 2346 | 0.01564 | 1031 | 0.00687 | 0.99361 | 0.00639 | 0.00644 | -0.00267 |

| 15764.0 | 1282 | 0.00855 | 421 | 0.00281 | 0.99376 | 0.00624 | 0.00628 | -0.00282 |

| 16740.0 | 1336 | 0.00891 | 461 | 0.00307 | 0.99401 | 0.00599 | 0.00602 | -0.00308 |

| 38900.0 | 1845 | 0.01230 | 735 | 0.00490 | 0.99404 | 0.00596 | 0.00600 | -0.00311 |

| 16580.0 | 168 | 0.00112 | 43 | 0.00029 | 0.99405 | 0.00595 | 0.00599 | -0.00311 |

| 31084.0 | 4557 | 0.03038 | 1279 | 0.00853 | 0.99408 | 0.00592 | 0.00596 | -0.00314 |

| 47894.0 | 2951 | 0.01968 | 772 | 0.00515 | 0.99424 | 0.00576 | 0.00579 | -0.00331 |

| 30700.0 | 175 | 0.00117 | 57 | 0.00038 | 0.99429 | 0.00571 | 0.00575 | -0.00336 |

| 34980.0 | 1227 | 0.00818 | 456 | 0.00304 | 0.99430 | 0.00570 | 0.00574 | -0.00337 |

| 24340.0 | 709 | 0.00473 | 251 | 0.00167 | 0.99436 | 0.00564 | 0.00567 | -0.00343 |

| 41180.0 | 1787 | 0.01191 | 527 | 0.00351 | 0.99440 | 0.00560 | 0.00563 | -0.00348 |

| 45104.0 | 358 | 0.00239 | 170 | 0.00113 | 0.99441 | 0.00559 | 0.00562 | -0.00349 |

| 42100.0 | 181 | 0.00121 | 53 | 0.00035 | 0.99448 | 0.00552 | 0.00556 | -0.00355 |

| 35614.0 | 2541 | 0.01694 | 850 | 0.00567 | 0.99449 | 0.00551 | 0.00554 | -0.00356 |

| 10580.0 | 365 | 0.00243 | 111 | 0.00074 | 0.99452 | 0.00548 | 0.00551 | -0.00359 |

| 12260.0 | 187 | 0.00125 | 52 | 0.00035 | 0.99465 | 0.00535 | 0.00538 | -0.00373 |

| 21660.0 | 188 | 0.00125 | 68 | 0.00045 | 0.99468 | 0.00532 | 0.00535 | -0.00376 |

| 41740.0 | 1890 | 0.01260 | 551 | 0.00367 | 0.99471 | 0.00529 | 0.00532 | -0.00378 |

| 49620.0 | 191 | 0.00127 | 57 | 0.00038 | 0.99476 | 0.00524 | 0.00526 | -0.00384 |

| 32820.0 | 385 | 0.00257 | 150 | 0.00100 | 0.99481 | 0.00519 | 0.00522 | -0.00388 |

| 14860.0 | 387 | 0.00258 | 104 | 0.00069 | 0.99483 | 0.00517 | 0.00519 | -0.00391 |

| 33460.0 | 2537 | 0.01692 | 847 | 0.00565 | 0.99488 | 0.00512 | 0.00515 | -0.00395 |

| 14454.0 | 1003 | 0.00669 | 287 | 0.00191 | 0.99501 | 0.00499 | 0.00501 | -0.00409 |

| 22020.0 | 202 | 0.00135 | 37 | 0.00025 | 0.99505 | 0.00495 | 0.00498 | -0.00413 |

| 12700.0 | 203 | 0.00135 | 63 | 0.00042 | 0.99507 | 0.00493 | 0.00495 | -0.00415 |

| 19430.0 | 205 | 0.00137 | 86 | 0.00057 | 0.99512 | 0.00488 | 0.00490 | -0.00420 |

| 35084.0 | 821 | 0.00547 | 307 | 0.00205 | 0.99513 | 0.00487 | 0.00490 | -0.00421 |

| 40140.0 | 2523 | 0.01682 | 1000 | 0.00667 | 0.99524 | 0.00476 | 0.00478 | -0.00432 |

| 39340.0 | 429 | 0.00286 | 192 | 0.00128 | 0.99534 | 0.00466 | 0.00468 | -0.00442 |

| 41540.0 | 216 | 0.00144 | 69 | 0.00046 | 0.99537 | 0.00463 | 0.00465 | -0.00445 |

| 23060.0 | 223 | 0.00149 | 75 | 0.00050 | 0.99552 | 0.00448 | 0.00450 | -0.00460 |

| 39580.0 | 937 | 0.00625 | 300 | 0.00200 | 0.99573 | 0.00427 | 0.00429 | -0.00482 |

| 12420.0 | 1221 | 0.00814 | 439 | 0.00293 | 0.99590 | 0.00410 | 0.00411 | -0.00499 |

| 39900.0 | 264 | 0.00176 | 105 | 0.00070 | 0.99621 | 0.00379 | 0.00380 | -0.00530 |

| 26900.0 | 1061 | 0.00707 | 452 | 0.00301 | 0.99623 | 0.00377 | 0.00378 | -0.00532 |

| 38300.0 | 800 | 0.00533 | 271 | 0.00181 | 0.99625 | 0.00375 | 0.00376 | -0.00534 |

| 40900.0 | 1614 | 0.01076 | 619 | 0.00413 | 0.99628 | 0.00372 | 0.00373 | -0.00537 |

| 44060.0 | 269 | 0.00179 | 106 | 0.00071 | 0.99628 | 0.00372 | 0.00373 | -0.00537 |

| 35644.0 | 272 | 0.00181 | 19 | 0.00013 | 0.99632 | 0.00368 | 0.00369 | -0.00541 |

| 18140.0 | 1093 | 0.00729 | 372 | 0.00248 | 0.99634 | 0.00366 | 0.00367 | -0.00543 |

| 19660.0 | 277 | 0.00185 | 121 | 0.00081 | 0.99639 | 0.00361 | 0.00362 | -0.00548 |

| 36084.0 | 1945 | 0.01297 | 473 | 0.00315 | 0.99640 | 0.00360 | 0.00361 | -0.00549 |

| 19804.0 | 565 | 0.00377 | 268 | 0.00179 | 0.99646 | 0.00354 | 0.00355 | -0.00555 |

| 17900.0 | 290 | 0.00193 | 102 | 0.00068 | 0.99655 | 0.00345 | 0.00346 | -0.00564 |

| 47664.0 | 1482 | 0.00988 | 685 | 0.00457 | 0.99663 | 0.00337 | 0.00339 | -0.00572 |

| 19740.0 | 2387 | 0.01591 | 941 | 0.00627 | 0.99665 | 0.00335 | 0.00336 | -0.00574 |

| 40484.0 | 308 | 0.00205 | 76 | 0.00051 | 0.99675 | 0.00325 | 0.00326 | -0.00585 |

| 17820.0 | 309 | 0.00206 | 171 | 0.00114 | 0.99676 | 0.00324 | 0.00325 | -0.00586 |

| 46700.0 | 313 | 0.00209 | 101 | 0.00067 | 0.99681 | 0.00319 | 0.00321 | -0.00590 |

| 28140.0 | 1299 | 0.00866 | 395 | 0.00263 | 0.99692 | 0.00308 | 0.00309 | -0.00601 |

| 30460.0 | 335 | 0.00223 | 106 | 0.00071 | 0.99701 | 0.00299 | 0.00299 | -0.00611 |

| 35154.0 | 707 | 0.00471 | 438 | 0.00292 | 0.99717 | 0.00283 | 0.00284 | -0.00627 |

| 15380.0 | 356 | 0.00237 | 115 | 0.00077 | 0.99719 | 0.00281 | 0.00282 | -0.00629 |

| 19780.0 | 360 | 0.00240 | 147 | 0.00098 | 0.99722 | 0.00278 | 0.00279 | -0.00632 |

| 44700.0 | 370 | 0.00247 | 175 | 0.00117 | 0.99730 | 0.00270 | 0.00271 | -0.00639 |

| 42220.0 | 375 | 0.00250 | 113 | 0.00075 | 0.99733 | 0.00267 | 0.00267 | -0.00643 |

| 31540.0 | 390 | 0.00260 | 114 | 0.00076 | 0.99744 | 0.00256 | 0.00257 | -0.00653 |

| 14260.0 | 418 | 0.00279 | 153 | 0.00102 | 0.99761 | 0.00239 | 0.00240 | -0.00670 |

| 23224.0 | 456 | 0.00304 | 160 | 0.00107 | 0.99781 | 0.00219 | 0.00220 | -0.00691 |

| 46060.0 | 477 | 0.00318 | 185 | 0.00123 | 0.99790 | 0.00210 | 0.00210 | -0.00700 |

| 25540.0 | 519 | 0.00346 | 157 | 0.00105 | 0.99807 | 0.00193 | 0.00193 | -0.00717 |

| 29404.0 | 527 | 0.00351 | 206 | 0.00137 | 0.99810 | 0.00190 | 0.00190 | -0.00720 |

| 41940.0 | 1068 | 0.00712 | 212 | 0.00141 | 0.99813 | 0.00187 | 0.00188 | -0.00723 |

| 11244.0 | 1840 | 0.01227 | 462 | 0.00308 | 0.99837 | 0.00163 | 0.00163 | -0.00747 |

| 41884.0 | 683 | 0.00455 | 105 | 0.00070 | 0.99854 | 0.00146 | 0.00147 | -0.00764 |

| 33874.0 | 909 | 0.00606 | 297 | 0.00198 | 0.99890 | 0.00110 | 0.00110 | -0.00800 |

| 42644.0 | 1857 | 0.01238 | 752 | 0.00501 | 0.99892 | 0.00108 | 0.00108 | -0.00802 |

| 47580.0 | 48 | 0.00032 | 24 | 0.00016 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 49660.0 | 160 | 0.00107 | 33 | 0.00022 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 49020.0 | 74 | 0.00049 | 23 | 0.00015 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 49420.0 | 60 | 0.00040 | 37 | 0.00025 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48060.0 | 14 | 0.00009 | 3 | 0.00002 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48140.0 | 66 | 0.00044 | 18 | 0.00012 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48260.0 | 14 | 0.00009 | 12 | 0.00008 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 47460.0 | 27 | 0.00018 | 10 | 0.00007 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48540.0 | 27 | 0.00018 | 10 | 0.00007 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48660.0 | 13 | 0.00009 | 6 | 0.00004 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48700.0 | 33 | 0.00022 | 11 | 0.00007 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 10540.0 | 36 | 0.00024 | 27 | 0.00018 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 48300.0 | 96 | 0.00064 | 30 | 0.00020 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 43420.0 | 22 | 0.00015 | 5 | 0.00003 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 10780.0 | 23 | 0.00015 | 10 | 0.00007 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 40340.0 | 133 | 0.00089 | 51 | 0.00034 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42044.0 | 92 | 0.00061 | 8 | 0.00005 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 11300.0 | 9 | 0.00006 | Missings | Missings | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 44940.0 | 26 | 0.00017 | 7 | 0.00005 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42060.0 | 14 | 0.00009 | 1 | 0.00001 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 44600.0 | 7 | 0.00005 | Missings | Missings | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 44420.0 | 40 | 0.00027 | 15 | 0.00010 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42140.0 | 79 | 0.00053 | 21 | 0.00014 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 44300.0 | 58 | 0.00039 | 15 | 0.00010 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 44220.0 | 52 | 0.00035 | 15 | 0.00010 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42200.0 | 196 | 0.00131 | 59 | 0.00039 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42340.0 | 169 | 0.00113 | 38 | 0.00025 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 39150.0 | 56 | 0.00037 | 60 | 0.00040 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 11500.0 | 32 | 0.00021 | 11 | 0.00007 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 42700.0 | 26 | 0.00017 | 6 | 0.00004 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |

| 43100.0 | 45 | 0.00030 | 13 | 0.00009 | 1.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | -0.00910 |