# Graphs

Problems and solutions for Graphs session on November 8, 2019.

### Table of Contents

* [Background](#background)

* [Problems](#problems)

* [1](#p1)

* [2](#p3)

* [Solutions](#solutions)

* [1](#s1)

* [2](#s3)

## Background

### What is a graph?

A graph is a data structure that organizes and shows relationships

between individual data nodes. However, a graph is not organized in a

heirarchal way the way a tree is. Nodes in a graph are not required

to be connected, and connections (or _edges_) between nodes can be

created and destroyed dynamically.

It is useful to observe that a tree is a form of a directed graph. The

edges are the connections leading to child nodes. In a tree, a

strict one-to-many relationship between nodes and their children is

required; generic graphs do not have this requirement.

### Why are graphs important?

Graphs are meaningful in the context of computer science because they

are an excellent model for entity relationships in many systems. For

example, most social media interactions can be represented using graphs.

If you are skeptical about the importance of graphs in computer science,

you should bear in mind that many highly competitive employers require

a thorough understanding of graphs and algorithms related to their

traversal and representation. If you want anecdotal examples of this,

feel free to ask.

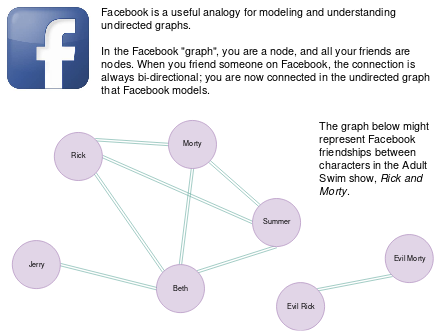

### Undirected Graphs

Undirected graphs have _bidirectional_ edges; any connection between

individual nodes is reflexively mirrored by the other, and the edge

can be traversed in either direction.

Facebook friendships are a useful analogy for undirected graphs; when

two people become friends on Facebook, both people are friends with

each other.

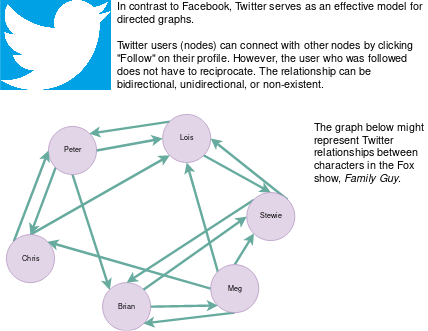

### Directed Graphs

Directed graphs have _unidirectional_ edges; an outbound edge to

another node is not necessarily reciprocated. Twitter serves as a

model for this kind of relationship.

### Representing Graph Edges

There are two common ways of representing edges between nodes in a

graph:

* An **adjacency list**

* An **adjacency matrix**

An adjacency list is unique to the node which owns it, and contains

pointers or references to the nodes it is connected to. Depending on

the structure of the graph, the lists may vary in size and contents.

We can represent the adjacency list with a `list`, `set`, or `map`

depending on the properties of the graph and the programmer's preference.

An adjacency matrix is a fixed-size structure, unlike the list equivalent,

and is 2-dimensional. Each possible node relationship (such as from

node A to node B) is referenced by the index pattern `matrix[A][B]`,

and the value at that cell is indicative of the existence of the

relationship. For example, for a directed graph, we might generate

an `N x N` matrix of boolean values, and when an edge is created

between nodes, we set the value of that cell to `true`; otherwise, the

value of the cell is `false`.

### Weighted Graphs

Until now, we have looked at graphs whose connections do not have any

special qualities. A common quality that graph edges might possess are

_weights_. Weights are usually associated with a cost or benefit of

the relationship between the nodes.

Consider a graph which represents

a map of highways between major US cities. Each graph edge, representing

a highway, might have a _weight_ that represents the number of miles

between those cities using that highway. This data structure can be

used to calculate the shortest route between two different cities,

for example. For more information about this subclass of problems,

we recommend reading about

[Dijkstra's Algorithm](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dijkstra's_algorithm).

Go to [Top](#top)

## Problems

### 1. Find Mutual Friends

Source: Lizzy

#### Scenario

Imagine a Facebook-esque social network that is represented by a graph. Each vertex represents a person's account,

and the edges between vertices represent friend status.

Write a method that counts the number of mutual friends between two people.

You can assume the `Vertex` class/struct is defined as follows:

```

class Vertex {

string name;

set friends;

}

```

#### Function Signature

```java

int findMutualFriends(Vertex p1, Vertex p2) {

// your code here

}

```

Go to [Solution](#s1) [Top](#top)

### 2. Boggle

Source: Lizzy

#### Scenario

In the [game of Boggle](https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boggle), 16

dice with English letters are arranged in a 4x4 grid, and players

identify as many real words as they can in 3 minutes.

A "real word" is constructed by stringing adjacent characters together

to form a common English word. Unique die faces which have been

used to construct a word may not be reused in that same word.

Adjacent characters include letters which are diagonally adjacent as

well as letters which are orthogonally adjacent.

Given a 2D array which represents a legal Boggle board and a string,

determine whether the string could be legally produced from the

board.

_Bonus: what if you wanted to find all valid words in a given board?

What kind of structures would you need? How would your implementation

change?_

#### Example Input

Input:

```

board: v e i e

l v t w

r e n x

w m p i

string: interview

```

Output: `true`

Explanation: The word "interview" is formed by tracing the word

from the bottom right-hand cell.

Input:

```

board: v e i e

l v t w

r e n x

w m p i

string: tent

```

Output: `false`

Explanation: We can form 't', 'te', and 'ten', but we cannot legally

form 'tent' in this board.

#### Function Signature

**D**esign **I**t **Y**ourself

Go to [Solution](#s3) [Top](#top)

## Solutions

### 1. Find Mutual Friends

Source: Tom, Lizzy, Google

#### Naive/Simple Solution

The solution for this problem is to find the intersection of both input

vertices set of friends. This solution copies one input vertex's set of friends into a `HashSet`,

calls `retainAll` method on this set, which iterates through the set while checking

if the next node is contained in the other input vertex's set of friends. If it is not, the `retainAll`

method will remove the node the iterator is pointing to and move to the next, leaving only common nodes (or mutual

friends) of both vertices. At this point, to get the count of mutual friends, access the size of the modified set

where vertex1 intersects vertex2.

The other thing to note is that this implementation's Vertex class scopes the `Set` members to private, hence the

`getFriends()` method call.

Java Implementation:

```java

int findMutualFriends(Vertex p1, Vertex p2) {

Set intersection = new HashSet<>(p1.getFriends());

intersection.retainAll(p2.getFriends());

return intersection.size();

}

```

#### Driver For Solution

[The java solution is here.](./find_mutual_friends/mutual.java)

Go to [Top](#top)

### 2. Boggle

Source: Lizzy

#### Solution

We can envision this board as an undirected unweighted graph.

Each die is a node, and all neighboring dice have edges connecting

them. When we find a word in the board, the word is represented by

a specific traversal route across the graph.

We can choose to traverse the graph depth- or breadth-first; our

solution traverses depth-first using a recursive function.

Because we don't want to repeat our usage of dice when we are forming

a word, we must track which nodes we have "visited", or included in

our word formation, up until this point. The provided solution uses

a set, but can be another structure of your choosing.

To begin the solution we call a method that is called `solve` in

this example. `solve` calls our recursive depth-first search

function for each cell in the grid.

```python

def solve(grid, word):

if not grid or not word:

return False

for row in range(len(grid)):

for col in range(len(grid[row])):

if dfs(grid, word, 0, row, col, set()):

return True

return False

```

Our recursive function does the following:

1. Check for base cases which might cause the current search path to

terminate as either true or false (see code for details).

2. Otherwise, we can proceed by searching surrounding cells. We mark

the current cell as visited and call our recursive function on

the surrounding cells, returning the inclusive OR of the result.

```python

def dfs(grid, word, word_idx, row, col, visited):

# handle edge cases:

# 1. check to ensure we have not processed entire word

# 2. check to ensure our indices are still in bounds

# 3. check to make sure we haven't visited this node

if word_idx >= len(word): return True

if row < 0 or row >= len(grid): return False

if col < 0 or col >= len(grid[0]): return False

if (row, col) in visited: return False

# we are still traversing graph; now, check for letter alignment

if grid[row][col] != word[word_idx]:

# letters are mismatched; terminate this search

return False

# keep searching; search in all 8 directions from current node

visited.add((row, col))

return dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row + 1, col, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row + 1, col + 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row + 1, col - 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row, col + 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row, col - 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row - 1, col + 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row - 1, col - 1, visited) or \

dfs(grid, word, word_idx + 1, row - 1, col, visited)

```

#### Bonus Question Solution

_Bonus: what if you wanted to find all valid words in a given board?

What kind of structures would you need? How would your implementation

change?_

Since our problem here has become more generic, we would do away with

matching individual characters based on an input string. However, we

require a set of words to compare our traversal path against. To

validate a specific path in the board, we can use one of two structures:

1. A "dictionary" of words, usually given as a `set`.

2. A prefix tree, or [trie](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trie).

For efficiency and elegant alignment with node traversal, a trie is

preferred. The reasons for this make for a good brain exercise;

feel free to ask why.

Now, when we are performing depth-first search of our board, we want

to have a way to reconstruct the word we are currently building. A

simple implementation would be to have the existing word passed in as

an argument to `dfs` so we can just append the current letter.

Each time we append a letter, we can check it against our valid word

list to see if we found a valid word. If that's the case, we want to

store the word somewhere. Because `dfs` is recursive, we have to be

careful about how we handle this requirement; a wrapper class around

a list/array is the most straightforward approach. Possible duplicate

words should be addressed in the solution.

#### Driver For Solution

For the basic problem, the [solution](./boggle/solution.py) and

[driver](./boggle/driver.py) are available. The solution's output is:

```console

$ python driver.py

Board:

v e i e

l v t w

r e n x

w m p i

For word 'interview', the result is True

For word 'tent', the result is False

Board:

For word 'a', the result is False

Board:

a

For word 'a', the result is True

For word 'i', the result is False

```

A coded solution for the bonus problem has not been provided and

has been left as an exercise for the reader.

Go to [Top](#top)