---

addenda:

- '[code](https://github.com/alexklapheke/trees)'

date: 1595378969

title: Cambridge street trees

---

This project now features an [interactive

map](https://alexklapheke.github.io/treemap/).

::: {.epigraph}

I think that I shall never see\

A billboard lovely as a tree.\

Indeed, unless the billboards fall\

I'll never see a tree at all.

:::

# Introduction

Every spring, the Callery pear down the street from me displays a

magnificent panoply of white blossoms, and releases... let's say a

*distinct* odor. A few months later, the tree of heaven in my backyard

drops an incredible torrent of flowers onto my porch, and within a few

months, another torrent of seed pods (this tree has it's own smell which

is marginally less unpleasant). It's a subtle difference between a

street lined with, say, honeylocusts and one lined with sycamores, but

trees really do go a long way in defining the character of a place,

making them a crucial consideration in urban planning.

Like many cities, Cambridge has long maintained a [dataset of all

municipal

trees](https://data.cambridgema.gov/Public-Works/Street-Trees/ni4i-5bnn),

including the species, location, date planted, and

[diameter](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diameter_at_breast_height).[^1]

By exploring this data, we can see what trends and patterns emerge, and

learn something about the arboreal life of our cities.

# Cleaning

Although the dataset does seem to cover every public tree, much of the

data is missing. For example, 83% of trees are missing the date they

were planted, presumably at least in part because they predate the

record system (a few of those that do list dates are from the 1970s).

There are many spurious values as well. Besides misaligned species names

(to be discussed in @sec:var), there are several misspelled genera

(e.g., "Planatus" for *Platanus*). The

diameter of each tree is listed, but the highest values are 154, 715,

745, 915, and 945 inches, corresponding respectively to about 13, 60,

62, 76, and 79 feet (the [stoutest tree in the

world](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81rbol_del_Tule) is only 46

feet in diameter), casting all values into some suspicion. The dataset

also lists properties such as number of trunks---one [katsura

tree](https://goo.gl/maps/fzSmAtdHHqaXnHv5A) has ten, and two, a

[Japanese tree lilac](https://goo.gl/maps/WjFi3ZdhdnzqxiG38) and a

[serviceberry](https://goo.gl/maps/Ma7ErKrC9TMTSWmu8) have eleven---and

things of municipal importance, such as whether there are overhead

wires, or whether the roots are emerging through the sidewalk.

I also included data about invasiveness, by grabbing the

[list](https://www.mass.gov/doc/prohibited-plant-list-sorted-by-scientific-name/download){.pdf}

of species considered invasive in Massachusetts, copying the scientific

names to a [text

file](https://github.com/alexklapheke/trees/blob/master/prohibited-species.txt),

and merging.

``` {.python}

invasive_species = pd.read_csv("prohibited-species.txt")

invasive_species["Invasive"] = True

trees = pd.merge(

left = trees,

right = invasive_species,

how = "left",

on = ["Genus", "species"]

)

trees["Invasive"].fillna(False, inplace=True)

```

The `SiteType` column helpfully tells us whether the tree is, in fact, a

tree at all, or a stump, a plot being prepared for a tree, etc. After

cleaning, I removing all of the latter cases---although really, the

cleaning was a process ongoing until the end.

# Varieties {#sec:var}

The obvious first thing to do after cleaning is look at what varieties

line the city's streets. @fig:gen shows the most popular genera as

recorded in the dataset (their corresponding common names are in

[Appendix A](#appendix-a-common-names-of-trees)).

{#fig:gen}

However, just knowing that the streets are lined with maples

(*Acer* spp.) doesn't tell us if they are

towering, stately silver maples (*A.

saccharinum*), or splendiferous red maples

(*A. rubrum*), or invasive Norway maples

(*A. platanoides*), nor does knowing

there are over 3,000 oaks (*Quercus* spp.) cast

light on which of the [over 600

species](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Quercus_species) they

comprise. We can break this graph down further by species (@fig:spec).

{#fig:spec}

There are some interesting takeaways here. For instance, not a single

public apple tree (genus *Malus*) has been

identified for species. This indicates that the data was not logged at

the time of planting; possibly, the species were identified by sight in

a later survey (ornamental apple trees are typically hard-to-identify

hybrids). Some of the "unknown species" labels are clearly in error.

*Liquidambar*, for example, contains only

four species, only one of which (*L.

styraciflua*) is grown ornamentally in the U.S., and is easily

distinguished from its relatives by its five-pointed leaves.[^2] More

alarmingly, *Ginkgo biloba* is the only

extant species in its entire class (a sister clade to the conifers), but

79 specimens are missing species information, and one is apparently of

*Ginkgo triacanthos*! Presumably, city arborists have not discovered a

new living fossil, but rather this row has gotten mixed up somehow

(maybe during merging) with a honeylocust,

*Gleditsia triacanthos*. We also see

such botanical novelties as *Ulmus cordata*, *Tilia calleryana*, and,

amusingly, *Acer acerifolia*---literally, a maple-leafed maple.

Besides the missing and spurious data, we see that over a third of

city-planted maples are Norway maples, which are now

[illegal](https://www.mass.gov/doc/prohibited-plant-list-sorted-by-scientific-name/download){.pdf}

in Massachusetts due to their propensity to crowd out native species. In

all, 2,282 trees considered invasive, representing five species, are

present in the dataset.

Invasive plants are not the only menace to biodiversity. We are lucky to

have over a thousand elms in Cambridge---after Dutch elm disease ravaged

populations in the 1960s and '70s, disease-resistant cultivars of

*Ulmus americana* were developed

which, along with fungicide, managed the destruction. The chestnut

blight fungus, introduced from East Asia around the turn of the 20th

century, has made the American chestnut

(*Castanea dentata*) all but

extinct, with a onetime population of several billion dwindling to a few

hundred today. So I was surprised to see four trees in the genus

*Castanea* in the dataset, but less

surprised when three turned out to be misidentified horse chestnuts

(*Aesculus hippocastanum*),[^3] and

the fourth was... wait for it... [a Norway

maple](https://goo.gl/maps/2Jar5K1Qrc5mFW5RA).

# Mapping

Every tree in the dataset has an associated latitude and longitude.

Indeed, the coordinates given for each tree display [incredible

precision](https://xkcd.com/2170/), giving no fewer than 15 decimal

places, making them [accurate](http://gis.stackexchange.com/a/8674) to

about 100 picometers, or approximately an atomic radius (I have no idea

how they chose which atom of the tree to use as a reference). In order

to map trees against Cambridge's [basemap

shapefiles](https://www.cambridgema.gov/GIS/gisdatadictionary/Basemap/BASEMAP_Roads),

I used [PyShp](https://pypi.org/project/pyshp/) to parse the shapefiles

and [PyCRS](https://pypi.org/project/PyCRS/) and

[PyProj](https://pypi.org/project/pyproj/) to convert from

[WGS84](https://epsg.io/4326) (i.e., standard latitude and longitude) to

[NAD 1983](https://epsg.io/102686), the coordinate system used in the

shapefiles.

``` {.python}

from pyproj import Transformer

# Convert between coordinate systems

transformer = Transformer.from_crs(

# WGS84 (EPSG:4326)

"+proj=longlat +a=6378137.0 +rf=298.257223563 +pm=0 +nodef",

# NAD 1983 StatePlane Massachusetts Mainland FIPS 2001 Feet

"+proj=lcc +lat_1=41.71666666666667 +lat_2=42.68333333333333 " +

"+lat_0=41 +lon_0=-71.5 +x_0=200000 +y_0=750000.0000000001 " +

"+ellps=GRS80 +datum=NAD83 +to_meter=0.3048006096012192 no_defs"

)

# Convert coordinates of invasive trees and plot on basemap

for label in invasives["label"].unique():

plt.scatter(

*transformer.transform(

invasives[invasives["label"] == label]["lon"].to_list(),

invasives[invasives["label"] == label]["lat"].to_list()

),

)

```

In @fig:invmap, we can see the locations of invasive species of tree.

Norway maples (*Acer platanoides*) are

predictably strewn across the city, but we see clusters of trees of

heaven (*Ailanthus altissima*), and

a few sizeable black locusts (*Robinia

pseudoacacia*), their impressive diameters indicating older

trees. Of course, many more specimens of these noxious species exist on

private land, and many of the worst invasive species are not trees at

all, such as reeds (*Phragmites

australis*) and garlic mustard

(*Alliaria petiolata*).

{#fig:invmap}

To see what trees are popular in different areas, I downloaded the

[neighborhood boundary

shapefiles](https://www.cambridgema.gov/GIS/gisdatadictionary/Boundary/BOUNDARY_CDDNeighborhoods),

and used [Shapely](https://pypi.org/project/Shapely/) to categorize each

latitude--longitude pair as being in one of the resulting polygons

(dismayingly, although the dataset has a `Neighborhood` column, it

doesn't contain a single data point). By filtering, we can see what the

most popular species is in each neighborhood.

{#fig:neighmap}

We can get an even more granular look by plotting each individual tree:

{#fig:neighmapdots}

Here we see some interesting patterns. The unidentified maples so

popular around MIT almost exclusively line the Charles River

embankment.[^4] The white ashes (*Fraxinus

americana*) in the Cambridge Highlands are concentrated in the

[Lusitania

Woods](https://www.google.com/maps/place/Lusitania+Field/@42.3879328,-71.1463062,17z)

by Fresh Pond. The other neighborhoods, though, are more chaotic, are

favor generally popular choices such as honeylocust. Mapping trees by

census block brings this wonderful chaos to life:

.](images/aaf055b3f1d38d8ff81ceba1ba6ab2e5499fd4ba.svg){#fig:blockmap}

# Planting dates

As mentioned above, only 17% of trees have a plant date listed, making

it difficult to find trends. Of course, it is still interesting to

examine the data we have---@fig:dates shows recorded plantings for the

genera in @fig:gen starting in 2007 since there are only a handful of

data points before then.

{#fig:dates}

In particular, it is to determine when invasives were planted---of the

2,282 invasive trees in the dataset, only five Norway maples have a date

listed. This is unsurprising---the "invasiveness" of invasives is

precisely their ability to aggressively reproduce. However, even of

these, we can see in @fig:acerdates that two were planted in 2013 and

2014, respectively, well after the [2006

law](https://www.mass.gov/service-details/prohibited-plant-list-background)

prohibiting such species took effect.

{#fig:acerdates}

There are some interesting trends visible in @fig:dates---a recent fad

for magnolias, a steady increase in serviceberry plantings

(*Amelanchier* spp.), and spikes in

pear tree plantings (nearly all of which are Callery pears,

*Pyrus calleryana*) in 2009 and

2017---although given the paucity of data, it is impossible to say if

they are real.

We can get another sense of trends by looking at location, rather than

genus.

{#fig:mapdates}

We can see several strings of orange and yellow where a whole row of

trees was planted all at once. In addition, unsurprisingly, the largest

trees tend to be the oldest, shown in purple.

There is much more I would like to do with this data---and much more,

and cleaner, data I'd like to have---but I've learned a lot about

Cambridge's trees, especially about the prevalence of invasive species

on my local streets.

# Appendix A: Common names of trees {#appendix-a-common-names-of-trees .unnumbered}

Genus Common name Family (APG IV [@apg4]) Population

------------------ --------------------- ------------------------- ------------

*Abies* fir Pinaceae 46

*Acer* maple Sapindaceae 4,875

*Aesculus* horse chestnut Sapindaceae 84

*Ailanthus* tree of heaven Simaroubaceae 67

*Amelanchier* serviceberry Rosaceae 499

*Betula* birch Betulaceae 374

*Carpinus* hornbeam Betulaceae 205

*Carya* hickory Juglandaceae 7

*Castanea* chestnut Fagaceae 4

*Catalpa* catalpa Bignoniaceae 27

*Cedrus* cedar Pinaceae 2

*Celtis* hackberry Cannabaceae 155

*Cercidiphyllum* katsura Cercidiphyllaceae 79

*Cercis* redbud Fabaceae 169

*Chionanthus* fringetre Oleaceae 5

*Cladrastis* yellowwood Fabaceae 122

*Cornus* dogwood Cornaceae 504

*Corylus* hazel Betulaceae 3

*Cotinus* smoketree Anacardiaceae 16

*Crataegus* hawthorn Rosaceae 82

*Enkianthus* enkianthus Ericaceae 1

*Eucommia* Chinese rubber tree Eucommiaceae 51

*Fagus* beech Fagaceae 130

*Fraxinus* ash Oleaceae 1,427

*Ginkgo* ginkgo Ginkgoaceae 467

*Gleditsia* honeylocust Fabaceae 2,637

*Gymnocladus* coffeetree Fabaceae 171

*Halesia* silverbell Styracaceae 9

*Hamamelis* witch hazel Hamamelidaceae 46

*Ilex* holly Aquifoliaceae 33

*Juglans* walnut Juglandaceae 19

*Juniperus* juniper Cupressaceae 104

*Koelreuteria* golden rain tree Sapindaceae 106

*Laburnum* golden rain tree Fabaceae 1

*Larix* larch Pinaceae 17

*Liquidambar* sweetgum Altingiaceae 377

*Liriodendron* tuliptree Magnoliaceae 177

*Maackia* maackia Fabaceae 26

*Magnolia* magnolia Magnoliaceae 244

*Malus* apple Rosaceae 762

*Metasequoia* dawn redwood Cupressaceae 49

*Morus* mulberry Moraceae 33

*Nyssa* tupelo Nyssaceae 25

*Ostrya* hophornbeam Betulaceae 40

*Oxydendrum* sourwood Ericaceae 15

*Parrotia* ironwood Hamamelidaceae 8

*Phellodendron* cork tree Rutaceae 59

*Picea* spruce Pinaceae 105

*Pinus* pine Pinaceae 964

*Platanus* sycamore Platanaceae 1,244

*Populus* poplar/aspen Salicaceae 192

*Prunus* cherry/plum Rosaceae 1,092

*Pseudotsuga* Douglas fir Pinaceae 11

*Ptelea* hoptree Rutaceae 1

*Pyrus* pear Rosaceae 1,072

*Quercus* oak Fagaceae 3,015

*Rhamnus* buckthorn Rhamnaceae 4

*Robinia* black locust Fabaceae 59

*Salix* willow Salicaceae 38

*Sassafras* sassafras Lauraceae 1

*Sciadopitys* umbrella pine Sciadopityaceae 1

*Sorbus* rowan Rosaceae 1

*Stewartia* tea tree Theaceae 19

*Styphnolobium* pagoda tree Fabaceae 357

*Styrax* storax Styracaceae 1

*Syringa* lilac Oleaceae 422

*Taxus* yew Taxaceae 26

*Thuja* arborvitae Cupressaceae 142

*Tilia* linden Malvaceae 1,544

*Tsuga* hemlock Pinaceae 101

*Ulmus* elm Ulmaceae 1,204

*Viburnum* viburnum Adoxaceae 20

*Zelkova* zelkova Ulmaceae 627

: Common names of the tree genera found in Cambridge. Note that, in

general, there is not a one-to-one correspondence between common and

scientific names, which is why the latter are generally preferred.

{\#tbl:latin}

[^1]: They've also compiled it into quite a nice [browsable

map](https://gis.cambridgema.gov/dpw/trees/trees_walk.html).

[OpenTrees.org](https://opentrees.org/) maintains a collection of

such datasets (possible fodder for future projects) as well as a

browsable map of all of them.

[^2]: Like so

([source](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NAS-062-c_Liquidambar_styraciflua.png))

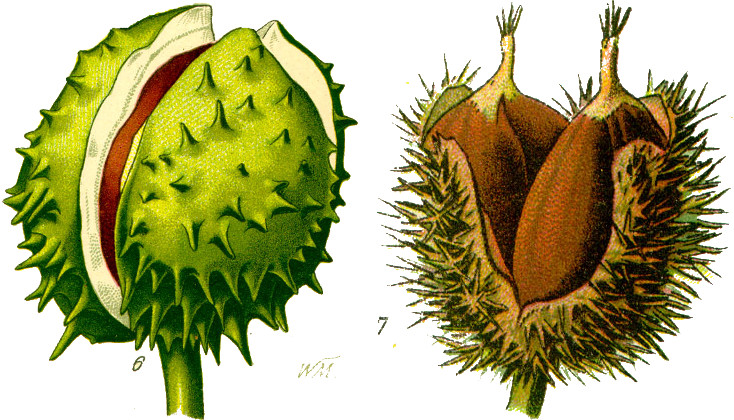

[^3]: An unrelated tree whose toxic fruit (left) looks very similar to

that of a true chestnut, *C.

sativa* (right) (sources:

[1](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illustration_Aesculus_hippocastanum0.jpg),

[2](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illustration_Castanea_sativa0.jpg)).

[^4]: Although unidentified, we can presume based on the placement that

these are of the same species.