# 1 Introduction

The ActDev project was created to address a gap in the evidence-base

needed for a sustainable future. Transport and planning policy areas

have tended to be dealt with in isolation, despite the clear linkages

between them. New housing development sites that are within walking and

cycling distance to work, public transport links and other key trip

attractors can help meet a range of policy objectives, not least the

government’s target of doubling cycling by 2025 and commitment to

becoming zero carbon by 2050.

The project sits at the interface between two major challenges: the

pressing need for sustainable transport (which can tackle a range of

issues from physical inactivity and obesity to air pollution)[1] and

affordable housing[2]. It builds on the previous ACTON project which

outlined available datasets with reference to four case study sites in

West Yorkshire (see

[cyipt.github.io/acton](https://cyipt.github.io/acton/articles/the-acton-project.html)

for details).

## 1.1 Aims and objectives

The aim of the 4 month ActDev project, which was funded by the [UK

Research and Innovation](https://www.ukri.org/) in December 2020, was to

demonstrate what is possible with new datasets and methods to help

people working in the planning system to support walking and cycling

uptake. The wider aim was to make case for evidence-based tools for

assessing and improving provision for active travel associated with new

developments nationwide, at every stage in the planning process. This

report outlines the context and methods underlying the report. For

information on how to use the tool, see the [ActDev

Manual](https://actdev.cyipt.bike/manual/).

The specific objectives were to create an actionable evidence base:

1. Provides a rating for the level of active travel provision (cycling

and walking) between development sites and key services, to

determine whether a location would be or is acceptable from health

perspectives.

2. For known planned/existing development sites, provide additional

analysis to inform specific improvements that could be made in

active travel provision and proximity of key services within walking

and cycling distance.

3. Makes the case for further work to create an interactive web

application (including the underlying evolving evidence base) to do

the above but on a national scale.

As outlined below, we believe we have achieved each of these objectives

with the publication of the prototype ActDev tool.

# 2 Project Components

To act as case studies for the project, we chose 35 large residential

development sites, representing a range of types of development

including urban extensions, urban regeneration schemes and new

settlements such as proposed Garden Villages. These included

developments that were completed, alongside others that were in progress

or had not yet reached construction. Further information about the

majority of the selected sites can be found in two Transport for New

Homes reports; the [Project Summary and Recommendations July

2018](https://www.transportfornewhomes.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/transport-for-new-homes-summary-web.pdf)

and [Garden Villages and Garden Towns: Visions and

Reality](https://www.transportfornewhomes.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/garden-village-visions.pdf).

## 2.1 Planning data

[UK Planit](https://www.planit.org.uk) is a national database of

planning applications based on scraping and aggregating data from the

websites of more than 400 planning authorities. It is an important data

source for the ActDev project and as part of the project the ability to

search across the full national dataset has been upgraded.

As part of previous work on the national planning dataset it was found

that there was no standardised indication of the type or size of a

development which is being planned.

Consequently an ‘app\_size’ classification was added to the the PlanIt

database with the aim of flagging large scale strategic residential

developments as ‘Large’ and other residential developments with >10

dwellings as ‘Medium’.

The classification rules for ‘app\_size’ used three sources of indirect

proxy indicators for larger scale developments:

1. The number of documents associated with the application (more than

100 indicating a larger development),

2. The number of days before a decision is taken (more than 8 weeks

indicating wide community interest),

3. And the type of an application (environmental impact assessments

often being associated with large developments).

Using these three indicators a crude classification was made, although

it was known that many applications of interest were being missed.

As part of the ActDev project, we used our 35 case study sites to

further improve the derivation of the ‘app\_size’ field within PlanIt.

All planning applications (approx. 6400) within the 35 areas were

reviewed and compared against existing classifications and known missing

cases. From this it was noted that many such applications included key

words (such as ‘garden village’) and often a number of prospective

residences in the ‘description’ field (eg ‘2,300 new mixed-tenure

dwellings’). Subsequently a new set of rules was developed within PlanIt

to extract the key words and a new ‘n\_dwellings’ field. These were then

used as additional proxy indicators of development scale within the

process for deriving the ‘app\_size’ classification (specifically

‘n\_dwellings’ more than 40 indicating ‘Large’ and more than 10

indicating ‘Medium’).

The resulting changes raised the proportion of ‘Large’ applications

within our case study sites from 3% to 11% and reduced ‘Medium’

applications from 10% to 8%. Note the percentage of Large applications

in this sample of 6400 across the 35 sites can be contrasted with the

percentage across the UK as a whole (15.7 million applications), of

which 1.3% are Large.

## 2.2 Access to local services

When choosing a development site, a key consideration is proximity to

local services such as shops, schools, parks, and other community

facilities. Nationally, access to a range of services has been

quantified through the Department for Transport’s [Journey Time

Statistics](https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/journey-time-statistics).

These record the average journey times to the closest food store,

primary school, secondary school, further education college, pharmacy,

GP surgery, hospital, and town centre, at the Lower Super Output Area

(LSOA) level. These LSOA level averages are derived from the mean of the

journey times from each Output Area within the LSOA.

Journey times are computed by three modes. The first mode uses a

combination of walking and public transport, depending on which of these

is fastest. The second mode is cycling, and the third is driving. Using

these statistics, we can get a picture of which locations allow easy

access to local services by walking and cycling. We can also compare

these journey times to journey times by car.

The JTS data does have some limitations. There is no information on the

quality of the route. For example, a fast cycling route may be possible

along a busy road, but in practice this might not be a feasible route

for most people. Similarly, we cannot differentiate between a well-used

high frequency bus service and an expensive, occasional service.

A further limitation is that the JTS data comprises LSOA-level averages,

so will not necessarily be representative of a given locality within

that LSOA. To get data that better matches a particular development

site, we have also written code to abstract chosen points of interest

from OpenStreetMap (OSM). For example, we can identify all of the

supermarkets on OSM that are close to a given site, and calculate

journey times from the site to these known destinations.

Town centres are a key destination, visited for a wide range of purposes

such as shopping, leisure, entertainment, employment, personal business

and to access onward travel. Using the same 2004 town centre dataset as

is used in the JTS statistics, we can identify the closest town centre

to a given site.

Travel to work is one of the most frequent journey purposes. We have

high degree of knowledge of employment locations through the use of

census data, as described in the following section.

## 2.3 Demographic and travel data

Travel to work accounted for [around

20%](https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/877039/commuting-in-england-1988-2015.pdf)

of total UK travel by distance before the coronavirus pandemic led

working from home levels to increase from around 5% to 40% of the

workforce.[3]

The best available travel information available at high levels of

geographic resolution in the UK is the 2011 travel to work

origin-destination data, which formed a foundation of the analysis. Some

of our case study sites were already partially complete by that date,

meaning the MSOA data reflects, in part, the actual journeys of site

residents themselves. However, in most cases the census data is best

seen as an indication of travel patterns in the local area surrounding a

site, rather than a reflection of the site itself.

We used MSOA data to demonstrate the methods although higher resolution

data could be used.

We developed new methods to ‘disaggregate’ origin-destination data,

enabling a greater diversity of destinations within a single MSOA zone,

as illustrated in Figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2.1: Desire lines for commuter journeys from Leeds Climate

Innovation District, following disaggregation of origin-destination data

to represent multiple origin and destination points within each MSOA

zone

## 2.4 Journey routing and road characteristics

Having obtained data on commute destinations and modes of travel, the

next step was to identify the routes on the transport network. For all

desire lines lying within the large study area around each site, we

generated cycling and walking routes for the journeys to work. We also

combined the individual routes into a series of route networks.

For cycle journeys to work, we used a set of algorithms created by

[CycleStreets.net](https://www.cyclestreets.net/). Three routing options

are available, representing fast, balanced and quiet routes. For the

fast routes, journey times are minimised. For the quiet routes, a

‘quietness’ parameter is maximised, to avoid routes that follow busy

roads. The balanced routes represent an intermediate between the fast

and quiet approaches.

Factors assessed during the routing include road type, cycle path width

and surface quality, barriers and obstructions, signage and route

legibility, among others

(). The gradient of route

segments is also taken into account.

It is useful to have these three different versions of the cycle routes,

because this can reveal places where for example a direct road may link

to a destination, but may be too busy for most people to consider

cycling along it. If the ‘quiet route’ to a given destination is

considerably longer than the ‘fast route’, it suggests that the

introduction of dedicated cycle infrastructure along the line of the

fast route would likely help to improve cycle accessibility.

For journeys to work on foot, we used the [Open Source Routing

Machine](http://project-osrm.org/) (OSRM) routing engine.

In addition to the commuter journeys, we also generated routes for

journeys from each site to the nearest town centre. This included both

walking and cycling routes, as long as the town centre was within 6 km

of the site. There is no data available on the number of journeys

residents make to their nearest town centre, however we know from the

[National Travel

Survey](https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/nts04-purpose-of-trips)

that across England in 2018/19, 15% of journeys were for commuting, 19%

were for shopping, 8% were for sport/entertainment, 9% were for personal

business, and 5% were for visiting friends (but not at a private home).

Many of these journeys are likely to involve going to the town centre,

either as a destination or as a means of accessing further travel. We

therefore made a simple assumption that the number of journeys to the

nearest town centre are equal to the total number of commuter journeys

from a site.

The generation of the routes allows estimation of parameters such as

route length, duration, mean busyness, maximum busyness, mean gradient

and maximum gradient. The next step was to combine the routes into a

route network. We produced separate route networks for walking routes,

fast cycle routes, balanced cycle routes, and quiet cycle routes. With

these we can see the total number of journeys on each road segment,

which can be analysed alongside segment level data on road busyness and

gradient.

## 2.5 Mode shift scenarios

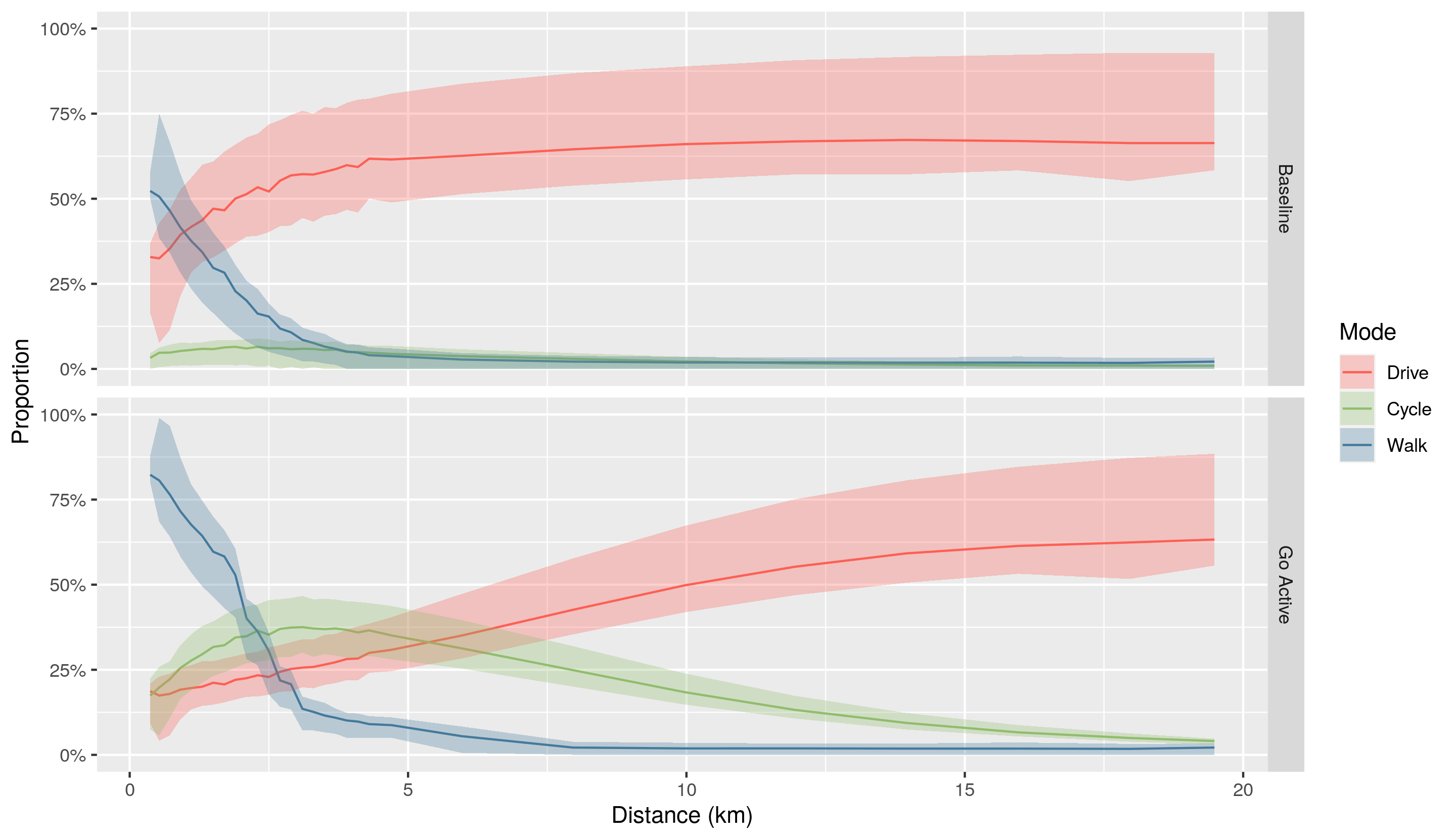

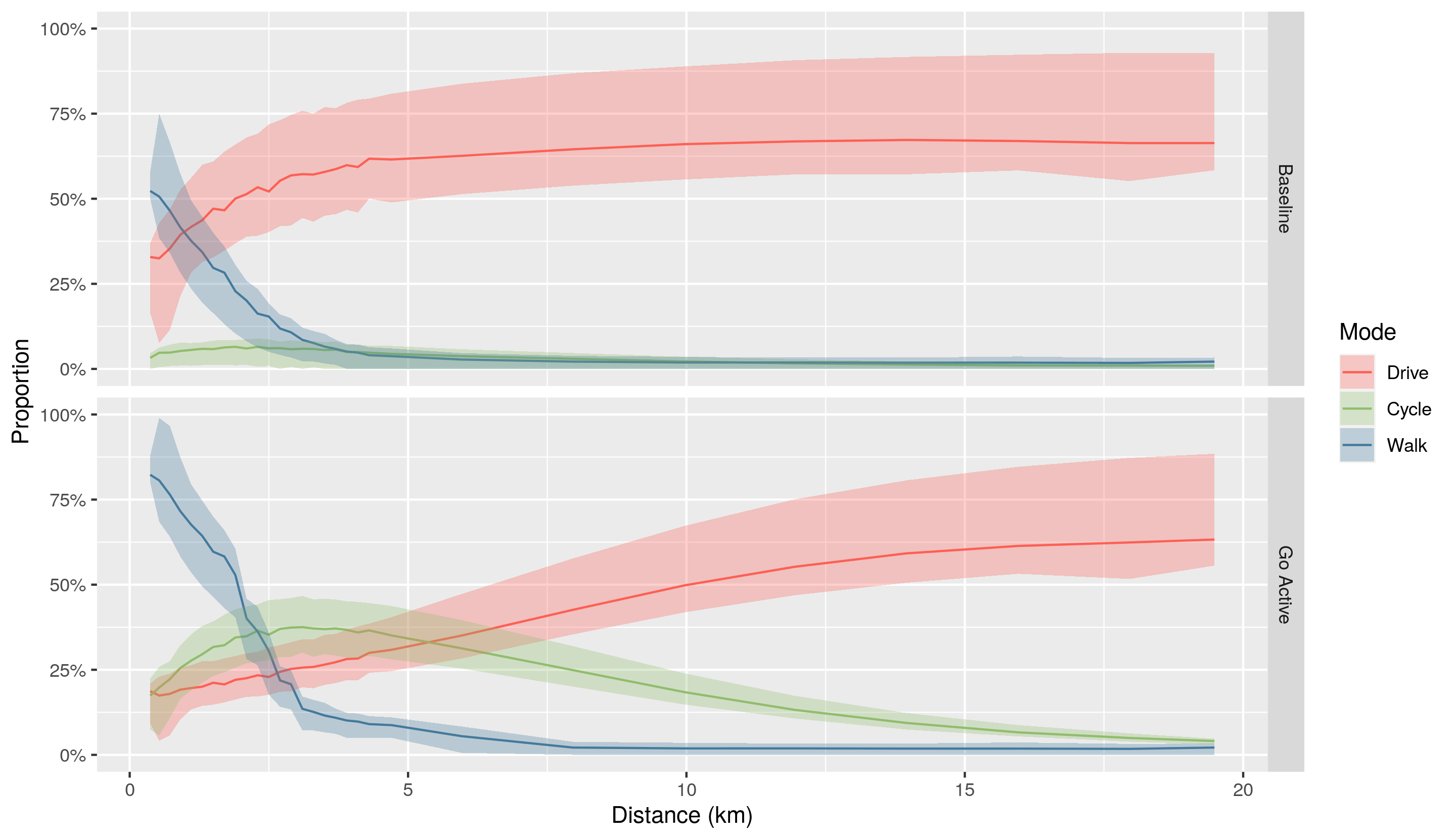

For each site, we generated two scenarios, Baseline and Go Active, as

illustrated in Figure 2.2. The 2011

Census journey to work data represents baseline conditions. For the

Baseline scenario, we simply adjusted this data to represent the

population, at completion, of the chosen residential development site,

rather than the population of the MSOA(s) that the site lies within. For

any given OD pair and mode: Baseline trips = 2011 Census trips from

local MSOA(s) / 2011 MSOA population(s) \* Number of dwellings at

completion \* Mean household size The data for MSOA population(s) and

mean household size both represent total population, rather than

population of working age.

The Go Active scenario represents the potential for increased uptake of

walking and cycling, in the presence of high quality infrastructure and

sustained investment. We calculated this increased uptake purely in

terms of a switch from car/van driving to walking or cycling. Other

modes of travel such as bus and rail were kept constant, and no change

was made to journeys that already took place by foot or bicycle in the

Baseline scenario. We also assumed that the journey destinations and the

total volume of travel remains the same as in the Baseline scenario.

To generate the increased cycle uptake in Go Active, we used the ‘Go

Dutch’ cycling uptake function from the [Propensity to Cycle

Tool](https://www.pct.bike/). This represents the proportion of journeys

that would be undertaken by bicycle if cycle mode share corresponded

with average cycling levels in the Netherlands. This function controls

for route length and hilliness.

To generate the increased walking uptake in Go Active, we used a set of

simple estimations. For journeys <= 2.0 km in length we assumed a

walking mode share 30% above baseline levels; for journeys of 2.0 - 2.5

km length, walking mode share was increased by 20%; for 2.5 - 3.0 km by

10%; and for 3.0 - 6.0 km by 5%. In future work we plan to refine the

uptake model, which is illustrated in Figure

2.2.

Figure 2.2: Overview of the uptake model underlying the Go Active

scenario compared with the Baseline scenario which is based on data from

the 2011 Census. The bands represent the range within which the majority

of origin-destination pairs fall, from the 20th to the 80th percentile.

## 2.6 Within-site metrics

The measures discussed so far relate to journeys to work or to other

destinations. The majority of the length of these journeys will take

place outside the boundaries of any particular new residential

development. However we also wanted to investigate the internal layout

of the sites themselves. In particular, the circuity of routes within a

site can reveal features relating to the design of the site. The

comparative circuity of routes by foot, by bicycle and by car can be

assessed.

To do this, we generated cycling, walking and driving routes for a set

of journeys between 20 random points within each site. We routed these

journeys using OSRM. Having obtained the sets of random points, we first

generated the driving journeys, then reset the exact origin and

destination points based on the results of this routing. This

constrained the points to be on the road network itself, preventing

cycle and walking route origins and destinations from spawning on

footpaths.

## 2.7 Traffic simulation

[A/B Street](https://github.com/a-b-street/abstreet#ab-street) is an

open source traffic simulator, designed to explore how gradual changes

to existing infrastructure can be modified to reduce dependency on motor

vehicles. It uses OpenStreetMap and many heuristics to build a detailed

model of roads, intersections, parking lots, and buildings, including

traffic signal timing, turn restrictions, and individual lanes. It

simulates the movement of individual people as pedestrians, cyclists,

car drivers, and public transit riders, using schedules input from

travel demand models such as the one developed as part of this project.

The user of A/B Street can modify the map by reconfiguring lanes (like

transforing street parking into a bike lane), modifying traffic signal

timing (like introducing a protected right turn stage), and setting

access restrictions (to model low traffic neighborhoods). The same

simulated people repeat their schedules, subject to the changed map, and

the user can explore the effects on individual people, or compare

aggregate results.

A/B Street aims to engage citizens with local transportation planning by

making it as easy as possible to imagine how changes might affect a

person’s commute. It could be used by city authorities to interactively

communicate proposed and ongoing projects; by the general public to

explore and submit ideas for improving their community; and by advocacy

groups to educate people about options for reducing automobile

dependency.

For ActDev, we imported each of the sites, synthesized a population

living in the site, and used 2011 census flow data to generate a

background population living in the larger study area and commuting

through it. A/B Street visualizes the existing road configuration and

locations of homes, shops, schools, and workplaces, according to

OpenStreetMap. The user can watch the simulation of individual people

living in the site follow through their workday route. When some traffic

bottleneck or issue with vehicles and cyclists mixing occurs, the user

can attempt to remedy the situation by modifying the road confguration,

and repeat the simulation to see how it may help.

# 3 Findings

The 35 case study sites encompass a wide range of development types,

from urban redevelopment schemes to suburban infill, urban fringe

expansion and entirely new settlements. The scale of these developments

also varies considerably. Most of the chosen sites will have over 1000

homes on completion, with up to 6900 at Hampton near Peterborough, but

some are smaller, the smallest being Tyersal Lane with only 270 new

homes. At least three of the sites are now entirely complete and another

24 are mostly or partly complete. In eight sites construction has not

yet begun, and for these sites we have not generated any in-site

metrics.

Table of site completion, number of dwellings and LA.

## 3.1 Existing travel patterns in the vicinity of the 35 case study sites

Unsurprisingly, existing travel patterns in the vicinity of these sites

vary greatly. The variation in commuter journeys is captured by the 2011

Census data as used in our Baseline scenario. It must be recognised that

these data represent travel patterns in the areas surrounding the sites,

rather than specifically for the sites themselves. The data are

aggregated at the MSOA level (these are zones with a mean population of

around 7800), so even for sites which were partially complete in 2011

the Baseline data is derived from a wide zone which stretches beyond the

site boundaries. With this caveat in mind, the differences in existing

travel patterns show some revealing patterns.

Walking mode share for these journeys varies from 3% at Upton and

Dickens Heath to 39% at Bath Western Riverside, with a mean of 11.4%.

Cycling mode share is as low as 1% at nine, mainly rural, sites. The

mean value is 4.3% and the maximum is 31%, at Great Kneighton in

Cambridge.

Driving mode share has a mean value of 65.5%. At five sites driving mode

share is > 80%, and four of these (Dickens Heath, Chapelford, Wynyard

and Upton) are sites in which some of the homes are known to have been

occupied prior to 2011. Only at five sites is driving mode share <

50%. These are all urban sites, with Kidbrooke Village (our only London

site) having the lowest driving mode share at 30%.

In terms of other modes of travel, Kidbrooke Village also has the

highest mode share for rail, and is one of only three sites - all in or

near London - having rail mode share > 10%. Bus mode share ranges

from 1% at Tresham to 17% at Leeds Climate Innovation District, with a

mean of 5.5%. Four of the seven sites with highest bus mode share are in

Leeds. The average mode share for other modes of travel, including

car/van passengers, motorbike and taxi, is 7%.

We expect to see a strong relationship between the distance travelled to

work and the mode of travel. For the vicinity of each site, we used the

2011 Census data to calculate the median commute distance. This ranges

from 1.7 km at Taunton Firepool to 16.0 km at Culm Garden Village, with

a mean of 7.9 km.

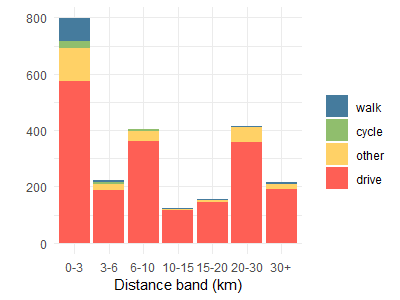

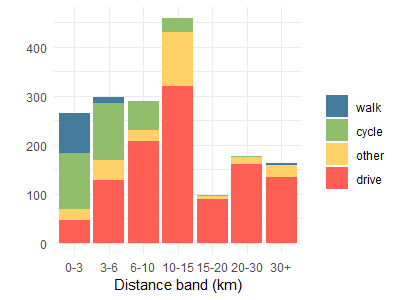

Combining the commute modes and distances, and using a standardised set

of distance bands, we can further interrogate the travel to work data,

as seen in the figure below. In this figure we compare commutes at Great

Kneighton (above) with those at Chapelford (below). We can see that

walking and cycling mostly occurs in the shorter distance bands. At

Chapelford the median commute distance is higher than at Great

Kneighton, and active modes also comprise a smaller proportion of the

short journeys.

## 3.2 Travel to town centres

Measured on the fast cycle route network, the median distance from our

case study sites to the nearest town centre is 3.2 km. Just three sites

lie within 2.0 km of the nearest town centre. At ten sites the nearest

town centre is >5.0 km away, the longest being Tresham Garden Village

with a distance of 23.9 km. This is an example of a site where there

appears to be no real cycle route to the nearest town. Using the

Euclidean distance, the town centre of Corby is 7.8 km from Tresham

Garden Village, linked by a direct road. This is a long way but could be

cycleable for some people. However, the local roads appear so

inhospitable to cycling that the fast cycling route follows a circuitous

path of almost 24 km in length.

## 3.3 Potential improvements for active travel - The Go Active scenario

Assuming existing travel patterns remain the same, in terms of the

locations of workplaces or other destinations, a key question is what

proportion of these journeys could theoretically switch from car/van

driving to walking or cycling? The answer will vary from site to site,

depending mainly on the distances from people’s homes to the

destinations of interest. Estimating this allows us to understand the

potential usership of new walking or cycling infrastructure, if

sustained investment was made in high quality active travel provision.

It lets us see how much walking and cycling uptake there could be under

the right circumstances. We can also see which sites are already close

to reaching these high levels of active travel, and which remain far

away from them. If existing walking and cycling levels are far below

their potential, this suggests there may be particular barriers that

need further investigation.

The proportion of commutes by foot under our Go Active scenario ranges

from 0% to 48%, with a mean of 12%. It is zero in four sites because in

these places we identify no journeys less than 6km in length, which is

our maximum threshold distance for walking. These are typically remote

rural locations where new settlements have been proposed or constructed.

There are three urban sites - Bath Western Riverside, Taunton Firepool

and Leeds Climate Innovation District - which see > 40% of commutes

by foot in this scenario.

Commutes by bicycle in the Go Active scenario range from 5% at Ashton

Park and Tresham Garden Village to 63% at Great Kneighton in Cambridge.

The site with the second highest value, also in Cambridge, sees 36% of

commutes by bicycle. The mean proportion of cycle commuting in this

scenario is 18%. The proportion of commutes by car/van drivers is

typically lower in Go Active than in the Baseline scenario. It has a

mean of 52%, ranging from 18% at Kidbrooke Village to 83% at Tresham

Garden Village. We do not model changes in other modes of travel.

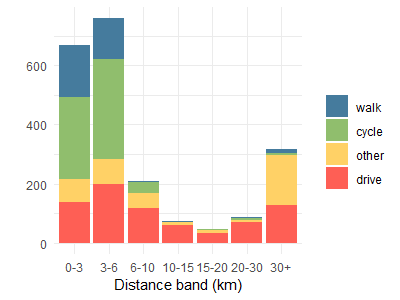

Studying the differences between the Baseline and Go Active scenarios,

we can see where there is potential for substantially increased

increased uptake of walking and cycling, given the right circumstances.

Of the 35 sites, the one with the greatest proportional increase in

walking from Baseline to Go Active scenario, is at Chapelford, where

walking mode share increases 250%, from 4% to 10%. This suggests that in

2011, the proportion of people walking at Chapelford was well below

potential.

Proportional increases in cycling between the two scenarios are much

greater than for walking. The greatest proportional increase in cycling,

from the Baseline to the Go Active scenario, is at Dickens Heath, where

cycling mode share increases 2000%, from 1% to 20%. The mean

proportional increase in cycling across all sites is 700%.

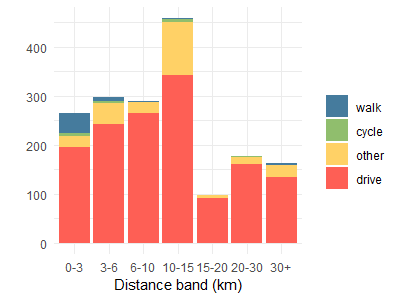

The following figure shows the Baseline (above) and Go Active (below)

scenarios for Dickens Heath. We can see that in 2011, 82% of commutes

here were by car/van drivers, but many of these could potentially switch

to cycling, if sufficient investment was made into safe, convenient

cycle routes.

# 4 Additional links and reading

For details on how to use the tool see the [ActDev

Manual](https://actdev.cyipt.bike/manual/).

For slides on the tool see [slides presented at the ActDev

Workshop](https://www.robinlovelace.net/presentations/actdev-slides.html).

To see the source code underlying the tool, see

.

[1]

[2]

[3] See the 3rd report from the Department for Transport

funded SaferActive report for details:

\`