# Benchmarks

* [Operation Categories](#operation-categories)

* [Copy](#copy)

* [Conditional Copy](#conditional-copy)

* [Transformation](#transformation)

* [Categorization](#categorization)

* [Conditions](#conditions)

* [Miscellaneous](#miscellaneous)

* [Summary](#benchmark-summary)

Benchmark Setup

### Measurement Process

Benchmarks use the [Java Microbenchmark Harness](https://github.com/openjdk/jmh) to ensure accurate results.

1,000 collections are randomly generated with sizes chosen from the following probability distribution in order to

resemble the real world:

- 35% between 0 and 10 elements

- 30% between 11 and 50 elements

- 20% between 51 and 200 elements

- 10% between 201 and 1,000 elements

- 5% between 1,001 and 10,000 elements

To measure the performance of an operation, we measure how many collections can be processed per second. This is

repeated across 27 configurations: 3 collection types (lists, arrays, & immutable arrays) and 9 data types (Boolean,

Int, String, etc.). When measuring the performance of a data type across the 3 collection types, each collection

operates on identical, randomly-generated data. See benchmark sources

in [pods4k-benchmarks](https://github.com/daniel-rusu/pods4k-benchmarks) for full details.

### Result Normalization

The relative throughput allows us say that an operation is `X` times faster when switching from one data structure to

another without talking about the exact throughput since that's dependent on the machine. So results are normalized

relative to the median list performance in each chart. Normalizing all results against the same value is important as

that allows us to gauge the impact of switching data structures, and also the impact of different data types.

**Example calculation:**

| Operation Performed On | Operation Throughput | Relative Throughput |

|------------------------|----------------------|---------------------|

| `List` | `1,200` ops/sec | `1.2` |

| `List`* | `1,000` ops/sec | `1.0` |

| `List` | `900` ops/sec | `0.9` |

| `BooleanArray` | `2,400` ops/sec | `2.4` |

| `IntArray` | `2,000` ops/sec | `2.0` |

| `FloatArray` | `1,800` ops/sec | `1.8` |

* Everything is normalized relative to `List` in this hypothetical example as that's the median list performance.

Value types

There are 9 Immutable Array types in this library. A generic `ImmutableArray` and a primitive type for each of the 8

base types, such as `ImmutableIntArray`. Since regular arrays also have primitive variants, like-for-like comparisons

are made with regular arrays (eg.`ImmutableFloatArray` vs.`FloatArray`).

The Immutable Arrays library makes every effort to minimize auto-boxing without sacrificing readability so that clean

code is efficient by default. Developers write natural-looking code without thinking about primitives or auto-boxing and

the library automatically binds to the most efficient specialization:

```kotlin

val names = immutableArrayOf("Dan", "Jill") // ImmutableArray

val luckyNumbers = immutableArrayOf(1, 2, 3) // ImmutableIntArray!!!

```

Unlike lists or regular arrays, working with Immutable Arrays makes it natural to end up operating on primitives even

when starting with generic types:

```kotlin

// people is an ImmutableArray

val weightsInKilograms = people.map { it.weightKg } // ImmutableFloatArray since weightKg is a Float

// ...

// Extra-fast without any extra developer effort!

val babyIsPresent = weightsInKilograms.any { it < 5.0f }

```

Benchmarking 9 value types (generic + 8 primitive types) aligns with the most natural usage of this library as

primitives are automatically used whenever possible.

## Operation Categories

### Copy

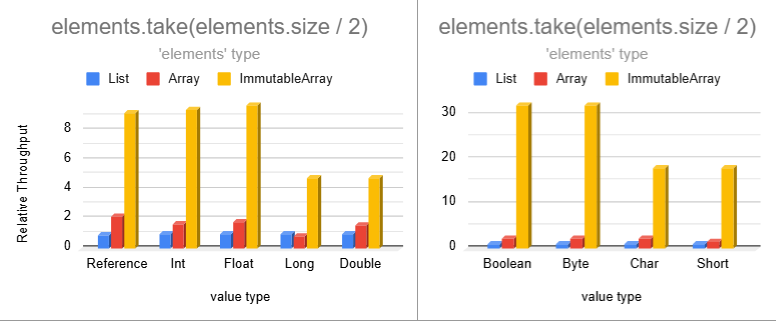

Operations that copy ranges of values have significantly higher performance than lists and even regular arrays. The

smaller data types are split into a separate chart to avoid skewing the chart axis since their performance is too high!

Operations on lists or regular arrays produce lists accumulating values one element at a time. Immutable Array

operations generate immutable arrays in order to maintain immutability guarantees. This allows us to use bulk memory

operations to copy multiple elements at a time and also avoid per-element bound checks.

The `drop` and `dropLast` operations have similar relative performance. Omitting those for brevity.

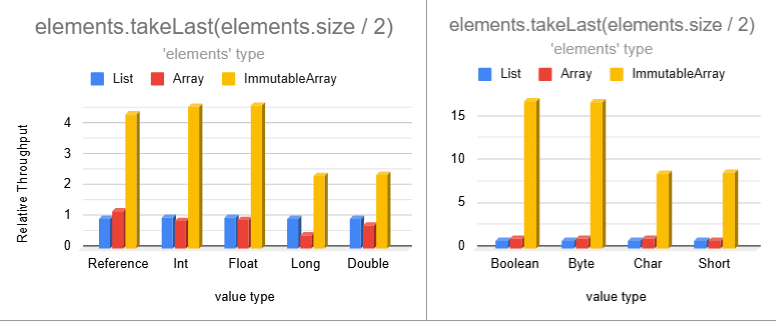

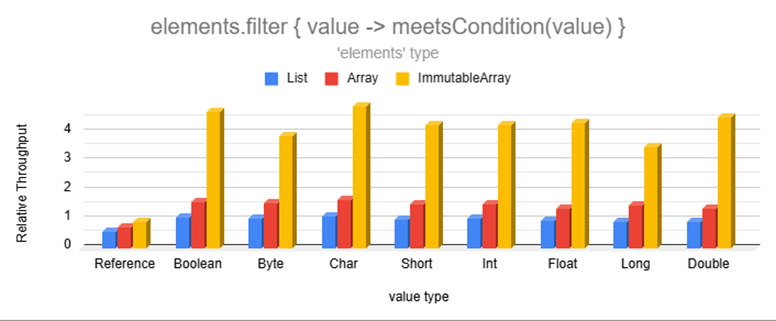

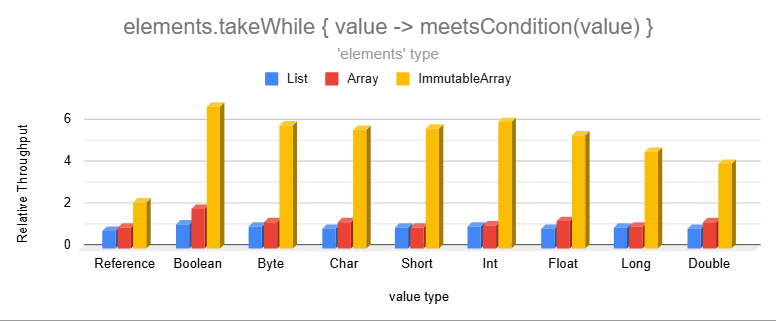

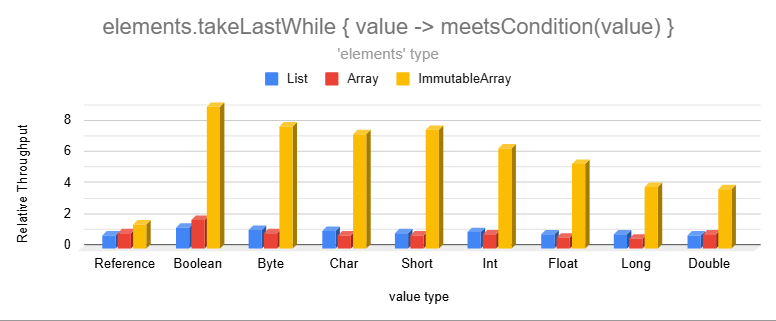

### Conditional Copy

Operations that conditionally copy elements can be significantly faster than lists and regular arrays

Although filtering can't take advantage of bulk copy operations since the accepted values are scattered, representing

accepted elements as individual binary bits unlocked low-level bitwise operations resulting in seemingly impossible

performance.

These are much faster because producing an Immutable Array allows us to find the cutoff point and copy memory in bulk.

The `dropWhile` and `dropLastWhile` operations have even higher relative performance. Omitting those for brevity.

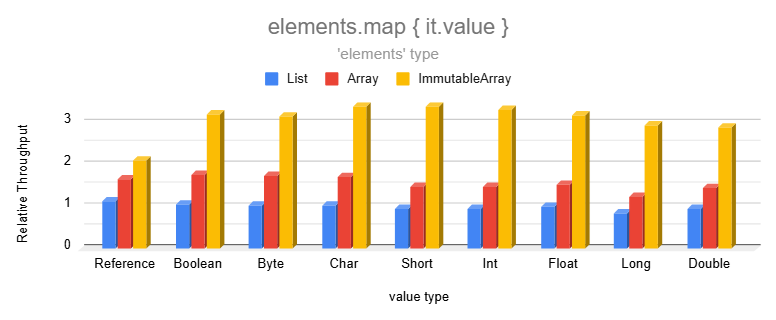

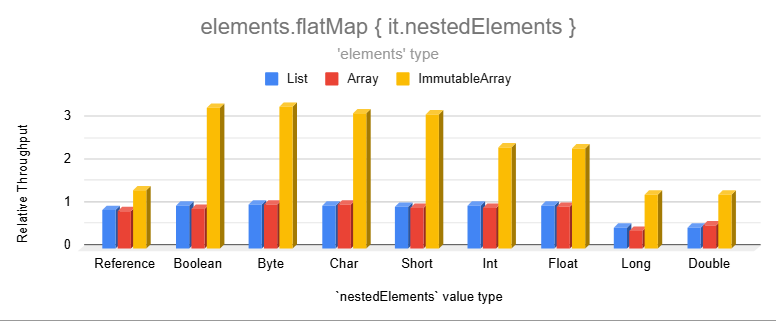

### Transformation

Transformations are significantly faster than lists and even regular arrays:

Immutable Arrays are faster than lists or regular arrays because they produce Immutable Arrays in order to maintain

immutability. This skips the list capacity check for each element and also avoids auto-boxing when transforming elements

into one of the 8 primitive types.

Note that `flatMap` on regular nested arrays is slightly slower than lists because the Kotlin standard library doesn't

have an overload for that. We used `elements.flatMap { it.nestedRegularArray.asList() }`as the most efficient

alternative since `asList()` returns a wrapper without copying the backing array.

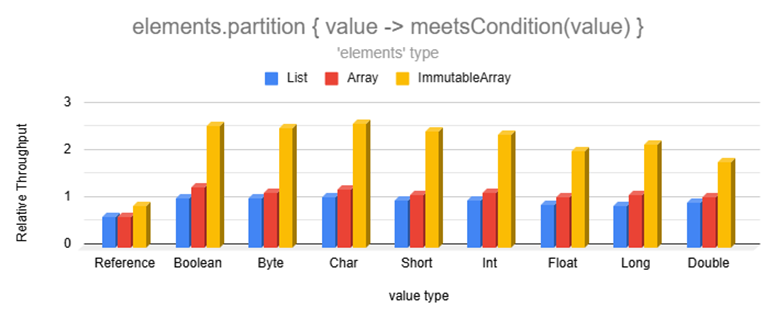

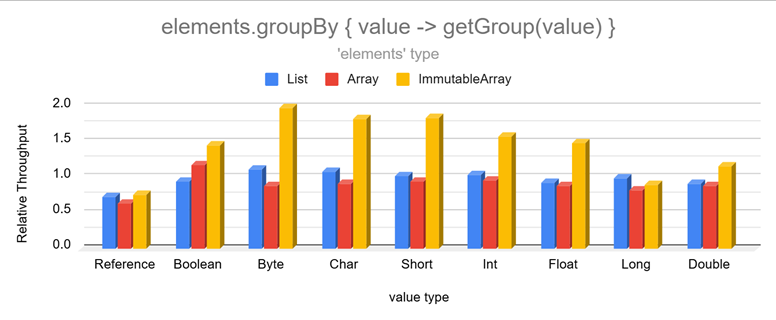

### Categorization

Categorizing is much faster than lists and even regular arrays:

Partition is so fast because it uses a perfectly-sized double-ended buffer avoiding resizing as elements are added to

either side.

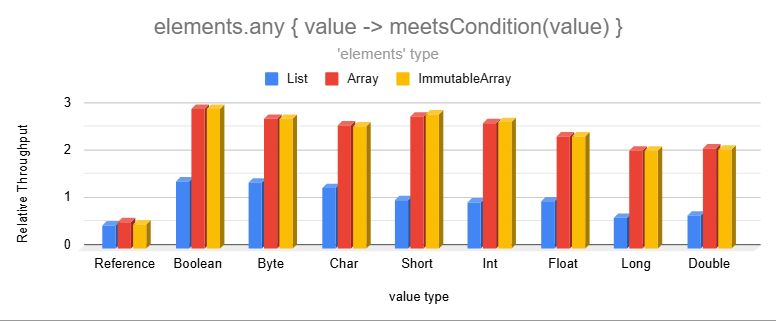

### Conditions

Immutable Arrays are much faster than lists when inspecting one of the 8 base data types:

Lists store generic types forcing primitive values to be auto-boxed. This makes inspecting their values slower as the

wrapper object introduces an extra layer of indirection.

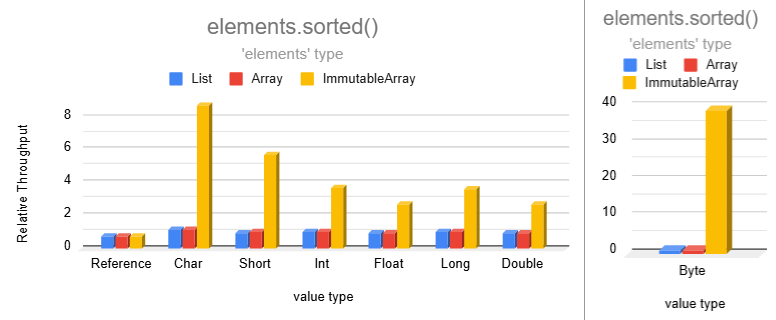

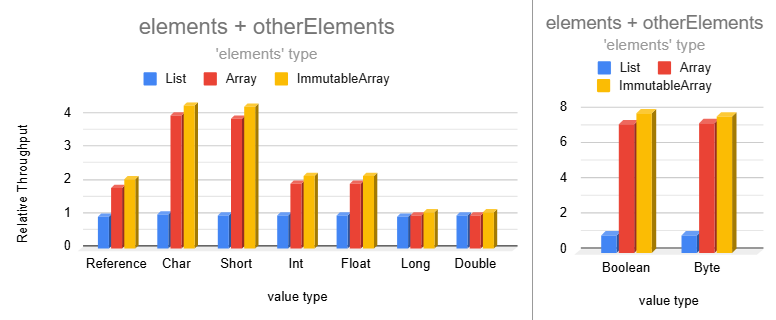

### Miscellaneous

Sorting becomes extremely fast for smaller data types!

Combining two immutable arrays into a larger one is much faster than lists for most data types:

## Benchmark Summary

Immutable arrays are between 2 to 8 times faster than lists for many common operations with some scenarios over 30 times

faster! Although there are many more operations, the above results should provide a pretty good representation of the

performance improvement of common non-trivial operations.

We don't usually think about primitives in Kotlin and the same is true with Immutable Arrays. Immutable Arrays allows us

to write clean list-like code, and the library automatically uses primitives when possible. This reduces memory

consumption and improves performance without having to think about primitives:

```kotlin

// primitive ImmutableFloatArray since weightKg is a Float

val weightsInKilograms = people.map { it.weightKg }

// Extra-fast while looking the same as regular list code

val babyIsPresent = weightsInKilograms.any { it < 5.0f }

```