SAMUEL AXON - 11/3/2017, 1:47 PM

A lot has changed in the decade since Apple shared its first iPhone with the world, but most people's relationships to their smartphones have not changed for a while. After an explosion of innovation, we’ve mostly seen incremental updates to processing power, security features, screen size, cameras, and software in recent years. These have added up over time, but the progress has rarely revolutionized this product area or its users' experience.

Generally, people have understandably been fine with that. Stability is good for consumers. We now see our phones as practical tools, not as anything extraordinary—not anything that opens up exciting and relevant new possibilities in our professional and personal lives like those earliest iPhone and Android phones did.

Some enthusiasts have nevertheless lamented that this is no longer the Apple whose products, once perceived as truly groundbreaking, excited them. But even more so than usual, Apple wants buyers to see this new phone, the most expensive iPhone yet released, as revolutionary. It has positioned iPhone X as a blueprint for all handsets to come.

But is the iPhone X that significant? Is the future actually here—for real this time, after that marketing suggestion has been thrown around so much that we’ve tuned it out? And even if it is, is it worth the potential pains of early adoption for newer technologies like Face ID and OLED?

I’ll give you a hint: this phone does three notable new things, all in one device. As a certain turtlenecked man once said, "Are you getting it?"

JUMP TO ENDPAGE 1 OF 8

Let’s start with the specifications. The iPhone X is very close to the iPhone 8 Plus here. The screen is notably different in that it is OLED and supports HDR; it also has a much higher resolution (2436×1125 pixels instead of 1920x1080).

| SPECS AT A GLANCE: APPLE IPHONE X | |

|---|---|

| SCREEN | 2436×1125 5.8-inch (458PPI) pressure-sensitive touchscreen |

| OS | iOS 11 |

| CPU | Apple A11 Bionic (2x high-performance cores, 4x low-power cores) |

| RAM | 3 GB |

| GPU | Apple-made A11 Bionic GPU |

| STORAGE | 64 or 256GB |

| NETWORKING | 802.11ac Wi-Fi (866Mbps), Bluetooth 5, NFC (Apple Pay only) |

| PORTS | Lightning |

| CAMERA | 12MP rear camera with dual OIS, 7MP front camera |

| SIZE | 5.65" x 2.79” x 0.30" (143.6 x 70.9 x 7.7mm) |

| WEIGHT | 6.14oz (174g) |

| BATTERY | 2716 mAh |

| STARTING PRICE | $999 unlocked |

| OTHER PERKS | Wireless charging, OLED, HDR, Face ID |

The iPhone X has more battery capacity, and Apple has added optical image stabilization to the rear camera’s telephoto lens. In the iPhone 8 Plus, only the wide angle had OIS. The iPhone X also has stereo speakers. The iPhone X includes Apple’s A11 Bionic SoC, which impressed in performance tests when we reviewed the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus.

The iPhone X’s industrial design—at least what’s obviously visible to your average user—seems to be catching up more than it is innovating.

By now, you probably already know that Apple has removed the home button to make room for more screen on the front. This fits the philosophy of removing technological barriers to the user experience, something the company has talked about for years. But despite Apple’s stated commitment to that philosophy, competing handsets beat the iPhone to some aspects of this design. Nevertheless, it is a return to form and a positive step forward.

At 6.14oz, the iPhone X weighs less than any of the previously released Plus models, but it's heavier than all the other iPhones. The iPhone X weighs almost exactly the same as Samsung’s Galaxy S8+. At 0.30 inches, it’s slightly thicker than the iPhone 7 or 8, but it’s not the thickest iPhone we’ve seen—that honor belongs to the iPhone 3GS at 0.48 inches.

The back of the phone is made of glass, with only two markings—Apple’s logo and the word “iPhone.” There’s still a camera bump. The dual cameras are now aligned vertically instead of horizontally (this helps with AR applications) and the flash is now integrated into the bump.

A lot of people want as little glass as possible in their phones, in part because glass can shatter. We’re not able to do a drop test with our loaner unit from Apple, but looking at it, my gut tells me it would probably fare about as well as the iPhone 8—which is to say, not that well. It’s not ideal, but the aluminum used in the iPhone 7 could be a problem for wireless charging, so here we are.

There’s still no headphone jack, just a Lightning port on the bottom. The side buttons are the same as you’ve seen on all recent iPhones: volume up and down and a mute switch on one side, and a prominent interaction button and SIM card slot on the other. This button now performs several of the functions that the home button used to.

Apple says this device is “all screen” in its marketing materials, but that's not quite true. There are still bezels on all sides—they’re just drastically smaller—and there is, of course, the notch at the top that houses the front-facing camera and several other components. More on that controversial element soon.

The display’s edges are now rounded at the corners. This subtle change will require a little bit of new thinking from app designers. In general, it doesn’t cause many problems, though if you zoom a rectangular video to fill the full screen, parts of the image will get cut off to fit the new shape.

The rounded edges look pleasant, and they add to the intended feeling that the screen is just sinking into the sides of the phone. Apple says that the panel continues and folds behind the edges; subpixel anti-aliasing is applied to address distortion. The real benefit with this design is that you get a much larger screen without ending up with a massive, difficult-to-use-with-small-hands phablet.

Even though the part of the panel visible to the user doesn’t fold, some parts of what I’ve just described are similar to what Samsung has done with its folding OLED displays. Of course, Samsung made this display, but Apple says it applied extra, custom innovations on top of what Samsung has already achieved. It’s not straight off of Samsung’s shelves.

This is just one of many examples in this device of Apple waiting out an emerging technology until it reaches the point where the company has either reasonably or arbitrarily concluded that the kinks have been ironed out. The same could be said of the Face ID apparatus, which is, in practice, a more advanced Microsoft Kinect, and of the OLED display.

In that process of adoption, refinement, and sometimes creation, technology detritus is cast to the side. Ideas that Apple heralded as groundbreaking just a few short years ago are now discarded to the annals of iPhone history, like Touch ID and haptic feedback on the home button (since, well, there isn’t a home button anymore).

The screen reaches all the way to the top of the phone, but the front-facing camera and Face ID sensors (along with some other hardware) are housed up there. Rather than leave a bit more bezel at the top, Apple has gone with what people have started calling “the notch”—a small sliver that cuts just a little bit into the screen.

It’s a little odd at first. Just leaving more bezel at the top to accommodate all the hardware like some other phone-makers have done might have been a more elegant solution to some eyes. That said, I quickly stopped noticing or caring. There’s no Platonic ideal of a mobile device display resting in the quintessential aether somewhere, dictating that there can’t be any intrusion into any part of the screen. Why not have a notch?

Well, it does present some challenges to app and Web designers. Apple has provided developers and designers with guidelines for working with the top part of the display. As in the past, developers are given a designated “safe area” in which they may confidently place UI elements. This gives direction to developers and designers so they can keep important content away from the notch. In landscape mode, for example, the notch falls to the side and will always cut into the view for apps that have been updated for iPhone X. The safe area dictates that no content should appear past a certain invisible line on the side of the screen.

It’s a little more to think about, but it’s all packaged in concepts and practices with which iOS developers are already familiar.

Other aspects of the screen eliminate some of the situations in which the notch could be egregious.

Personally, I would be most bothered by the notch if I was watching a movie or TV show on my phone, and it was cutting into the picture. In fact, I would consider that outright unacceptable. But consider the aspect ratio and the OLED display. In landscape mode, the display area can comfortably be made wider than any current TV or film aspect ratio. Even the 2.40:1 aspect ratio leaves letterbox borders on the sides that are big enough to encompass the entire notch, as well as small ones at the top and bottom; the more common 16:9 aspect ratio is even narrower.

That means that unless you’re the sort of person who leaves the image zoomed in to fill the screen, thereby cutting off part of the image already (shame on you, say the film buffs of the world), the notch never cuts into the picture.

If the iPhone X had an LCD display, though, I would still find this irritating. That’s because backlit LCD displays don’t really do true blacks; there’s always a grayish glow behind even the darkest parts of the screen. The contrast between the jet black notch and the backlit, “black” parts of the screen would be noticeable. In an OLED display, though, the blacks are completely, absolutely black. It is as if that part of the screen is not even on.

This is part of why many people like OLED screens in TVs so much. Most TVs have a 16:9 aspect ratio, which means that movies in 2.40:1 are letterboxed. On an LCD, the letterbox border has a soft glow, and it’s annoying. On OLED, it just looks like that part of the TV is off. The same applies here, and the notch blends completely into the letterbox border. It just looks like a black bezel. I’d rather not have a bezel at all, but it’s better than a soft, gray glow.

In most situations, either the notch isn’t getting in the way, or it’s not even visible. Even most people who find the very idea of it terrible will get used to it quickly—if not on the iPhone X, then on the numerous future phones from Apple (and others) that will follow its lead.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 2 OF 8

Since most people will be upgrading from the iPhone 7, let's talk about how the iPhone X’s camera compares to that one. First off, the A11 Bionic features a dual-core Neural Engine in the image signal processor (ISP). This is used for portrait lighting and some other features related to photography.

The rear camera still has the same resolution—12MP—but the sensor is bigger, which should result in some improvements. The iPhone X has two cameras on the back—one wide angle and one telephoto—just like the iPhone 7 Plus. The iPhone 7 didn’t have the telephoto lens.

But this aspect of the camera is even improved over the iPhone 7 Plus. That phone had optical image stabilization (OIS) on the wide-angle lens but not the telephoto. The iPhone X has dual OIS. This will really help, especially in low light and in macro-style photography, because it means the phone can dial in a slower shutter speed to grab more light while simultaneously mitigating the inevitable shake from the photographer's hands. To further drive that point home, the iPhone X and its 8-series brethren employ hardware noise reduction, performed by the ISP. The LED flash has also been improved.

HDR photos have been improved over the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus, and they are now on by default—there’s not even an option to turn them off anymore, actually. The phone makes the choice for you. Additionally, the telephoto lens has gone from an ƒ/2.8 aperture to ƒ/2.4—more help for low-light scenarios.

On the video side of things, you can now record 4K video at 24fps, 30fps, and 60fps. The iPhone 7 was limited to 30fps for this resolution. The iPhone 7 Plus was the only one of last year’s iPhones to support 6x digital zoom in videos; the iPhone X follows in its footsteps. The iPhone 7 could do slow motion, but only in 1080p at 120fps and 720p at 240fps. Like the iPhone 8 models, the iPhone X can now do 1080p at 240fps.

The front-facing camera is still 7MP, but the inclusion of the TrueDepth sensor array allows for portrait mode and portrait lighting in selfies. Portrait mode adds a sort of simulated bokeh effect, thanks to the ISP. Selfies are probably where people would want this feature the most, so the ability to do it on the front-facing camera is a plus.

Portrait lighting was introduced with the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus; it allows you to tweak the lighting in a photo of someone’s face either in real time as you’re taking the picture or after the picture has been taken. The following lighting scenarios are supported:

The feature is still in beta, and my results weren’t inspiring when I reviewed the iPhone 8. For example, it kept capturing the space behind people’s glasses in unintended ways. It hasn’t improved here in either camera array; the examples above are uncharacteristically fine, but then it goes and produces a mess like this, with the wall cutting into the backdrop.

I can see it becoming popular as it improves, but right now it’s not very impressive.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 3 OF 8

The iPhone X is equipped with the new TrueDepth sensor array. The array projects more than 30,000 infrared dots on your face to map it. It's used both to secure your phone with that map of your face and to power certain AR features, which are available to app developers.

It’s the iPhone X’s wildest, most ambitious idea. Face ID completely replaces Touch ID on the iPhone X as your primary authentication method, and while the AR features are, at launch, mostly limited to fun curiosities like animated emojis and Snapchat filters, they could open up some fascinating new possibilities in future apps.

To set Face ID up, you hold the phone at a normal distance from your face and rotate your head twice like you’re painting a circle with your nose. An on-screen indicator guides you through this. It doesn’t even take 10 seconds.

You can only store one face with Face ID, so you can’t share a device or give your significant other access. The equivalent was possible with Touch ID because it let you store several fingerprints. That was presumably so you could, say, use either your index finger or your thumb to open your phone, but some people—myself included—used that to allow multiple users access.

Once your face is saved, the phone will always be looking for it. You can tap the screen to turn it on after it has gone to sleep. At the top, you’ll see an icon modeled after a lock. If the lock is open, Face ID sees you and will let you access whatever would have otherwise been restricted. If it’s closed, it doesn’t see the trusted face, and few interactions are available.

The success rate is high, but there is room for improvement. With many dozens of attempts in a day, it has failed to recognize me right away maybe twice a day since I set it up. Sometimes I just had to tweak the angle a little bit and it quickly resolved. Two times in the past four days, I’ve had to give up and enter my password.

It’s more frustrating that it almost always takes about a quarter or half second longer than you’d ideally want. It’s comparable to the first generation of Touch ID in this sense. The second generation made a big difference in that tech. Hopefully this phone’s successor will do the same.

By default, the iPhone X hides most information from notifications on the lock screen until it sees your face. An imposter using your phone would just see that you have an e-mail via the Spark app, but they wouldn’t see the headline or the sender. As soon as Face ID recognizes you, e-mail subject lines and tweet contents appear.

The iPhone X can also use Face ID to automatically input passwords into fields on the Web. This taps into Apple’s existing password saving and management system, and the developer of the website doesn’t seem to have to do anything. It just happens.

Like Touch ID, Face ID is also open to third-party app developers. I was happy to see that every app I tried that supported Touch ID already worked with Face ID instead, with no action required from the app developer. For example, I log in to my bank app with the fingerprint sensor on my iPhone 7. On the iPhone X, the same app automatically used Face ID to authenticate me, even though Bank of America’s app hadn’t been updated (it still had text referring to Touch ID). I didn’t have to change any settings on my end.

Face ID opens all sorts of doors. Apple claims it is more secure than Touch ID. It enables neat features like the ones I just described. It has accessibility ramifications in that it could enable new hands-free interactions with the device. There are surely applications we haven’t even thought of yet.

I was always able to use Face ID to unlock as far as the length of my arm when holding the phone. I was also pleasantly surprised by the horizontal angles at which it would work. Angling the phone vertically seemed more likely to trip it up. It also works in darkness. You might run into the most problems in heavy, direct sunlight, which could interfere with the tech. It could encounter trouble if there’s a bright light right behind your head, too.

It can deal with some changes to your face, but not others. It will usually cope with a haircut. Makeup shouldn’t be a problem, either, nor should glasses. As long as it can completely see your eyes, your nose, and your mouth, it works. Because Face ID relies on the IR spectrum at 940nm, some sunglasses will block it, but others won’t. In some cases, disabling attention detection—by which Face ID only unlocks if it can tell you’re looking at it—could address blockage by sunglasses.

Gradual changes like gaining weight or growing a beard are also covered. Face ID uses machine learning to re-train itself as you change.

There are some things you could do before that you can’t now, though. For example, I sometimes place my phone on a table or desk and use it like a table-top screen. I can still wake it while it sits flat on a table by swiping up the screen to unlock, then swiping up again at the Face ID prompt to bring up the passcode instead. But you can’t use Face ID to log in as seamlessly as you could with Touch ID in this case, even if you try to awkwardly orient your face to look down at the screen (it won’t recognize you at that angle). You need to pick up the phone and hold it in front of your face.

Apple Pay has changed as well. Previously, you could just move your phone within range of the payment machine while your thumb was on the sensor. A second later, the transaction was complete. Now you have to move the phone up to the payment machine, show your face, and double tap the side button. It’s not difficult, but the Touch ID way was simpler.

According to Apple’s Face ID security guide, “The probability that a random person in the population could look at your iPhone X and unlock it using Face ID is approximately 1 in 1,000,000 (versus 1 in 50,000 for Touch ID).” These odds change if you have a twin or another sibling who just looks a lot like you. It’s an edge case, but there are already videos on YouTube of twins beating Face ID.

Apple tested the technology extensively with masks to make sure that’s not a viable option. Obviously, since it’s a 3D map, a photo won’t get an intruder into your phone. If someone has taken you hostage and is trying to show your face to the phone to open it, there is some risk, but you have two protections in such an instance. First, the phone requires you to look at it by default. If you can avoid looking at the screen, it won’t unlock. Second, holding down the side buttons for a moment will turn off Face ID and require a passcode to proceed.

If you turn off or restart the device, if you haven’t unlocked it in 48 hours, or if five unsuccessful Face ID attempts have been made, you have to enter your passcode.

And what if someone tries to access usable information about your face by compromising your device? It seems unlikely. Apple’s documentation says something about efforts to prevent that:

Once it confirms the presence of an attentive face, the TrueDepth camera projects and reads over 30,000 infrared dots to form a depth map of the face, along with a 2D infrared image. This data is used to create a sequence of 2D images and depth maps, which are digitally signed and sent to the Secure Enclave. To counter both digital and physical spoofs, the TrueDepth camera randomizes the sequence of 2D images and depth map captures, and projects a device-specific random pattern. A portion of the A11 Bionic chip’s neural engine—protected within the Secure Enclave—transforms this data into a mathematical representation and compares that representation to the enrolled facial data. This enrolled facial data is itself a mathematical representation of your face captured across a variety of poses.

There are privacy considerations; Reuters reported that the ACLU had raised some concerns. Reportedly, Apple allows developers to fetch data like customers’ facial expressions from Face ID if they prompt the user and ask for explicit permission. This data could theoretically be used for sentiment tracking when displaying ads, in one example. But Apple tells developers they’re not allowed to use the information for that. It may be difficult to enforce across the numerous apps on the App Store, though.

And what about Apple itself? Apple’s Craig Federighi was insistent in telling TechCrunch that it’s not storing customers’ face data anywhere but the local device. “We do not gather customer data when you enroll in Face ID,” he said. “It stays on your device, we do not send it to the cloud for training data.” He added that Apple does not give any data to law enforcement, because it doesn’t have the data to give.

Apple is trying to cover all the bases here, but it’s a new technology. There’s always the risk that something will be missed.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 4 OF 8

Apple has showcased the AR potential of the TrueDepth sensor array by adding a feature called Animojis to Messages. It’s exactly what it sounds like; they’re 3D emojis that animate and move based on your own facial expressions.

You can record a 10-second animoji with your voice included and send it to a friend or family member. They're sent as video files, so friends who have other phones can view them.

They’re cute, and a few third-party apps like Snapchat are already offering other things like this. I’ll admit I had a blast recording goofy messages for my fiancée with this, but it’s a frivolous glimpse at something that could be applied in far more impactful ways in the future.

As noted when going over the security implications of the TrueDepth sensor, developers may use facial data in their apps. This data could open the floodgates to many new features and ideas as the technology is refined and improved in the coming months and years.

An app might be able to tell that you’re getting flustered and change its behavior. You could find yourself playing interactive fiction games that don’t just rely on you selecting dialogue responses—they read your facial expressions and adapt in-game characters’ actions and words to how you’re feeling or acting.

Hands-free interfaces could be developed for controlling an app based on your facial movements. You could chat live with someone over FaceTime or Skype while wearing a fictional face. It might even be used to assist in medical diagnosis in certain conditions.

Other devices have explored these possibilities to some degree previously, but here the technology is being refined. It’s also on a platform that could reach critical mass. It’s a cliché to say that the possibilities are endless, but it’s true.

iOS 11, thoroughly reviewedSwipe to unlock is back. That now-iconic interaction is once again how you open your phone, but this time you swipe from the bottom of the screen as the iPhone X reads your face. Generally speaking, every task you used to perform with the home button is now either replaced with that swiping-up gesture or the lone button on the right side of the phone.

The iPhone X runs iOS 11, just like the iPhone 8 does. I won’t get into every detail of iOS 11 here, but you can check out our thorough iOS 11 review to learn all about it. It’s still an excellent mobile operating system.

iOS 11 on the iPhone X differs from iOS 11 on previous devices in several ways. Changing the screen’s aspect ratio, cutting into it with the notch, and removing the home button meant that Apple had to rethink several parts of the user interface.

Removing that home button could be the most significant user interaction change that has ever occurred in iOS. When I first tried the iPhone X back in September, I wasn’t sure I liked the swiping gestures that have replaced it. But with only a little bit of day-to-day use, my tune has changed.

The swiping-up gesture is very similar to the one you’d use to unlock many Android devices, but it’s used for more than just unlocking on the iPhone X here.

Swiping up from the bottom while in an app will take you back to the home screen. Unless you’re viewing certain kinds of media, there’s usually a thin, white hint bar at the bottom of the interface that reminds you that you can do that. It’s surely helpful for new users, but it becomes superfluous once you’ve acclimated.

You might recall that a very similar gesture brings up the control center on other iPhones. Don’t worry; the control center is still accessible. To reach it, you swipe down from the top-right corner of the screen. The notification center can be found by swiping down from any other part of the top of the screen. When I first started using the phone, I kept getting one when I wanted the other, but I don’t have that problem after a couple of days. My muscle memory adjusted.

You can access the multitasking interface by performing the same swipe you use to exit an app or unlock the phone while stopping about halfway up the screen. The current app will move with your finger and join a lineup of cards similar to what you get when you double-tap the home button on the other iPhones.

However, swiping up on an app’s card doesn’t close out the app like it does on the home button-equipped handsets. Rather, it takes you back to the home screen. To close out apps, you have to use another gesture that we thought Apple had abandoned—holding down your finger on one of the apps for a brief moment, then tapping out red minus signs at the cards’ corners to close out those apps. I didn’t like that method back in 2010, and I don’t like it now. It just feels like too many steps.

That said, my favorite thing about iOS 11 on the iPhone X is multi-tasking related: while in any app, you can move your thumb quickly along the bottom of the screen (like you’re tracing the hint bar) to swipe between apps in either direction. It feels exactly like the three-finger gesture on MacBook touchpads to switch between spaces. In most cases, this has replaced the other multitasking interface for me.

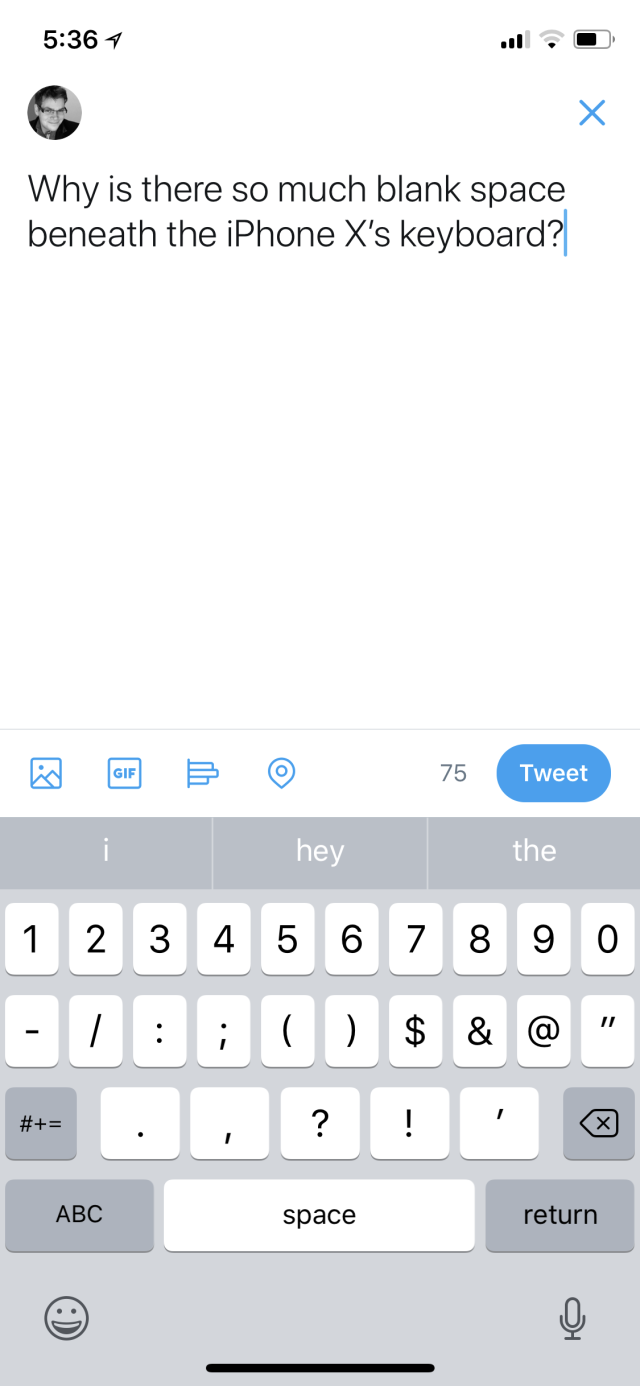

These swiping gestures at the bottom of the phone come with a price, though. Apple has generally instructed developers to avoid using the very bottom of the interface, and that has led to some weird looks even from Apple’s own apps. This is most obvious in the keyboard. Just look at this screenshot.

There’s a bunch of dead space beneath the keyboard; it looks odd. My hunch is that Apple determined through focus testing or some other method that accidental key presses would happen when swiping, or vice versa. It’s not a huge deal, it’s just strange-looking.

Also, iPhone Plus users will be disappointed to learn that despite the increased screen size, the iPhone X doesn’t support any of the more robust, landscape-mode versions of apps that the Plus handsets offer.

I’ll be honest—I don’t often use my phone as a phone. I’m much more likely to send a text, a Twitter DM, a Slack message, an e-mail, or yes, use emojis or touched up Snapchat images. For me, call quality has just been “fine” for a few iPhones now. Fortuitously, I was apartment hunting this week, so I had to take and make a lot more calls than I usually do. I can therefore tell you that call quality on the iPhone is still fine. I did also find that the iPhone X, like the iPhone 8, has the speakers to hold its own as a speaker phone for conference calls.

The iPhone X joins the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus in supporting Bluetooth 5.0, whereas the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus only support 4.2. Also, as with the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus and unlike the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus, certain iPhone X units support FDD-LTE band 66 and TD-LTE band 34.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 5 OF 8

Apple’s philosophy with the iPhone X’s display seems to be achieving the natural—natural blacks and natural colors. The phone adopts relatively new technologies that are only just maturing. Compromises were made, but the result is likely better than expected.

The iPhone 7’s display achieved 326 pixels per inch (ppi), and the iPhone 7 Plus achieved 401ppi. The iPhone X is a big step up in that regard; it’s 458ppi, with a resolution of 2,436 by 1,125 pixels.

Depending on how far you hold a phone from your eyes, resolution bumps may show diminishing returns. The bump in pixels per inch does bring the iPhone X closer to the LG V30, Samsung Galaxy S8+, and other competing flagship phones. But it's worth noting the iPhone X is still not quite there.

I’ll get into detail about how developers will deal with the change in resolution and some other UI considerations in a future article, but for now suffice it to say that, like the iPhone 8 Plus, the iPhone X uses the @3x scale factor for assets. However, it has the same width for the purpose of UI layout—375 points—as the iPhone 8. It adds significantly more points vertically, which some first-party apps use well and some waste.

All this is to say that the display is a little sharper and a lot taller, and Apple has made an effort to make the transition as seamless as possible for app developers. In most cases, developers won't have to provide any additional assets beyond what they've already been doing. But resolution isn’t what’s interesting about the iPhone X’s screen.

In high-end consumer televisions, OLED is arguably a leader. It’s the obvious choice for image quality-obsessed cinephiles and console gamers who hung on to their deprecated plasma TVs for years because they could never get onboard with LCD’s backlight bleeding, haloing, and historically so-so contrast ratios.

But for a variety of reasons, OLED has been a mixed bag in phones. Part of this is because the use cases for phones are different—yes, you might watch movies in the dark on your phone (I do), but it’s probably not what you do most—and part of it is that implementation differs.

There are two companies producing OLED panels in significant numbers—Samsung and LG. LG’s OLED TVs are acclaimed, but its phones have run into a lot of problems. Samsung’s smartphone OLED panels make some compromises, but on the whole, they’ve been better received in the marketplace than LG’s. Apple went with Samsung.

It seems to have been a good call. The contrast is remarkable, and I’ve seen none of the weirdness that people have encountered with the Pixel 2 XL, for example—other than color shifting (more on that in a minute). Color balance looks to my naked eye every bit as good as that on the iPhone 8. P3 is of course back, but HDR really helps. We haven’t had time to put the display through rigorous testing for color balance yet, but I’m optimistic.

Apple claims that the iPhone 8 and iPhone X together are the best displays on the market. Looking at the iPhone X side by side with other flagship phones, I can anecdotally say that it does look better than any other OLED phone display. Future tests and time will tell if the iPhone X’s color balance meets or exceeds that of the iPhone 8’s LCD, but to the naked eye there are absolutely no problems.

Apple claims 1,000,000:1 contrast ratio, but many manufacturers of devices with OLED displays actually claim infinite contrast ratio. It’s just semantics—the iPhone X’s display isn’t worse. On this display, black is black; there’s no nuance to it.

It took OLED a while to get there on handsets, but it’s there. I’m not looking back to LCD.

Burn-in has been reported in OLED displays as they age; the Google Pixel 2 XL, which uses an LG OLED panel, started exhibiting signs of this within days of launching. Apple claims to have taken extra steps to mitigate burn-in, but we’re not sure what those steps were. In any case, I haven’t experienced the problem after four days of use. It’s too soon to come to any conclusions, though.

Color shifting and viewing angles can also be a problem with OLEDs. In this case, Apple has definitely not broken new ground. When the display is tilted in a direction such that you begin viewing it at an angle rather than directly, it shifts very starkly to a cool blue. The iPhone 8 display shifts, too; however, the iPhone X shifts more dramatically and more quickly. I also found the shifting to be much more pronounced than it is on the Samsung Galaxy S8+.

It’s the sort of thing that is probably not really an issue with a smartphone. How often do you use your phone at much of an angle? But even users who aren’t snobs about this sort of thing will notice it when operating their phones laid flat on desks or tables.

There's also HDR here. To reference the TV side of things again, this is arguably the most significant development for enjoying video content since high definition.

The iPhone X supports both Dolby Vision and the HDR-10 standard. There's content for it in iTunes' movies and TV stores, but there aren't many other places to get it yet. Of course, a key component of those standards is mastering content in 12- or 10-bit color. The iPhone X’s screen is still only 8-bit, which is what you expect from SDR.

Apple claims that some kind of software wizardry is in play to use the 10-bit information in a file and render it on an 8-bit display in a way that is superior to just working with 8-bit content. I’m not sure what to make of that; there’s only so much you can do when the hardware is limited to 8-bit color. But Apple hasn’t gone public with details here.

As with other phones or computer displays, this is not HDR without compromises—at least not by the standards to which video and TV aficionados are accustomed. Nevertheless, Apple claims two additional stops of dynamic range over its previous phone.

But anyone with vision can look at the iPhone 7 or 8 and the iPhone X side by side and conclude that the iPhone X’s display is obviously better. If the iPhone 8’s SDR screen was some army of millions of pixels, the iPhone X’s victory in the battle of user impressions would be an unequivocal massacre.

Part of it is the absolute blacks of OLED. Part of it is HDR. Some of it is the subtle, subjective experience of a screen that reaches almost edge to edge. A lot of it is these things and others working together. Even Samsung’s excellent Galaxy S8+ display doesn’t quite match it. By many metrics, both objective and subjective, it is the best smartphone display I have seen.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 6 OF 8

The iPhone X runs on the A11 Bionic chip—the same one that powers the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus. We were impressed by that chip’s performance when we tested it in our iPhone 8 review. Our iPhone X benchmarks have shown very similar results, and we remain impressed. Along with the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus, the iPhone X is the fastest phone we have ever tested.

The iPhone 7’s A10 SoC had four cores—two high-performance and two efficiency cores. The A11 features six cores (two high-performance and four efficiency), and every core can be active at once. By contrast, the A10 could only use two at a time.

The A11 chipset also marks the first time Apple has engineered its own GPU. The three-core GPU replaces previous offerings from Imagination Technologies, which were already great. Performance isn’t as dramatically improved here as it is with CPU tasks, but it’s still a step up over the previous generation of iPhones.

Much has already been written about Apple’s efforts in augmented reality, which accelerated with the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus, but it’s so key to what the iPhone X is that some of it must be repeated here. Apple has brought augmented reality intent to most components that it has updated in this phone. For example, the cameras are now aligned vertically; this is in part because most augmented reality apps run in landscape mode, and by placing the cameras in this arrangement, depth sensing is improved.

All of this CPU and GPU power serves the AR mission, too. They, along with the improved Metal 2 graphics API, allow rendering detailed 3D assets and physics while also processing high-quality images on the camera and showing them on the screen together. Apple has also improved the accuracy of the accelerometer and gyroscope, which are key for AR experiences.

And there's ARKit, a software development basis for augmented reality applications. Google and others have competing platforms that also show promise. That said, ARKit is already supported by millions of iPhones—iPhone 6S and later. Apple has done a lot of the hard work to build an AR platform that developers can use as a strong starting point in creating new apps that work well with all this hardware.

The iPhone X is comprehensively built with AR as its primary concern, with numerous components all serving that same goal in co-supportive ways. The strong performance is at the heart of it all. Existing AR games' and apps' tech really impresses—especially tabletop strategy game The Machines.

Apple CEO Tim Cook has said he believes that AR on iOS will be an explosion of innovation on the level of the original App Store. I'm not sure I'd go quite that far, but Apple has bet big on it at least being the biggest app gold rush in recent years. The apps we see now are neat, but the best is surely yet to come.

Apple’s statements on battery life for the iPhone X confuse expectations a bit. On one hand, the company claims that the iPhone X “lasts up to two hours longer than iPhone 7.” This is hard to actually test in a quantifiable way, because that claim applies to whatever Apple internally considers to be normal daily usage—a cocktail of various tasks that Apple believes represents the average user’s habits. We don’t know the ingredients.

Apple claims 21 hours of talk time over the iPhone 7’s 3G talk time estimate of 14 hours and up to 12 hours of “Internet use.” While Apple’s spec sheets previously broke down Internet use estimates into different numbers for 3G, LTE, and Wi-Fi, the iPhone X spec sheet just provides one Internet use number. Who knows what that means, exactly.

There is a promise of up to 60 hours of wireless audio playback compared to 40 on the iPhone 7, though.

There’s a huge potential boon to battery life in OLED displays: pixels are individually lit, so when a part of the screen is black, the pixels in that area should not be drawing power in an ideal implementation. On the other hand, some past OLED panels have been less efficient when showing bright images than LCDs, which have seen more refinement over the years.

Apple hasn’t made any UI changes to make more of the screen dark in any of its apps, even though in theory that might have produced some battery life gains. That said, there is notably more battery capacity in the iPhone X than in the iPhone 7 or 7 Plus. Apple managed to fit more capacity in part by utilizing a new, double-layered main logic board that saved space compared to the some prior designs.

But with Face ID, OLED, and a significantly larger screen, does that added battery capacity really result in improved battery life, or does it just keep the status quo?

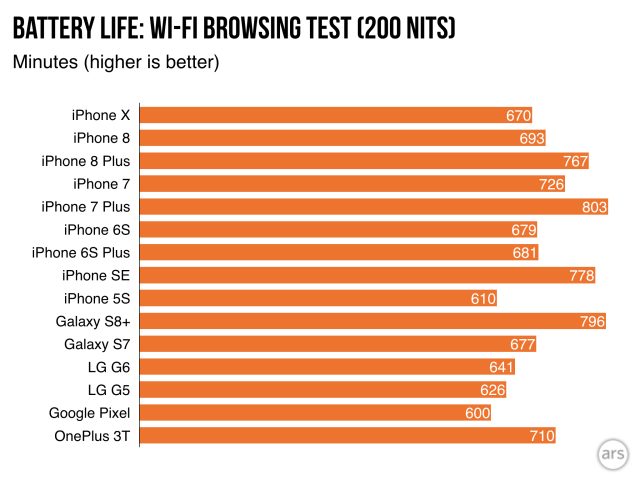

We ran a test to determine battery life when browsing the Web on Wi-Fi. When we run this test, we set the screen brightness to 200 nits and run a script that automatically reloads a series of static webpages over and over until the battery dies. We run this test twice and average the results.

Note that the iPhone 8, 8 Plus, and X were all running iOS 11 in this test, but the iPhone 7 and earlier were tested on earlier versions of iOS—whatever version each device launched with. The goal here is to compare battery life for these phones at their respective launches; results might be different with older phones running newer software.

These tests can’t possibly confirm or deny Apple’s claim of two additional hours in typical use, since we’re not testing typical use—and what does that mean anyway? But I did use the iPhone X as my main handset for a few days, and my anecdotal experience was that the battery life seemed about the same as that of my iPhone 7 running iOS 11.

Like the iPhone 8 and 8 Plus, the iPhone X supports wireless charging using the Qi standard. There are already several third-party charging pads on the market, and Apple plans to release its own charging pad that would charge an iPhone, an Apple Watch, and AirPods simultaneously.

iPhone 8 and 8 Plus review: The curious case of the time-traveling phoneI’ve already said quite a lot about this in both our Qi wireless charging explainer and our iPhone 8 review, but I’ll touch on the most important points here. The iPhone X uses a technology called inductive power transfer. There are two coils—one in the phone, and the other in the charger. The coil in the charger induces a current in the phone’s coil by generating an electromagnetic field.

Wireless charging is convenient, especially for topping off your phone by leaving it on a charging pad on your desk while you work, but it’s not as fast as wired charging. The third-party chargers that Apple is currently pushing max out at 7.5 watts—a lot less than some other chargers on the market. But there’s more to it than wattage, in any case.

We tested wireless charging on both Belkin and Mophie charging pads and found that, as expected, the iPhone charges more slowly on these pads than it does when plugged into a wall. This gap is widened further by the iPhone X’s support for fast charging from high-wattage chargers.

To take advantage of that, you’ll have to buy a USB-C to Lightning cable to connect the phone to a higher-wattage power adapter—for example, the 29W, 61W, or 87W MacBook chargers. It’s also possible with third-party adapters, though results are not guaranteed in that case. Testing with a MacBook Pro charger, I found it to be much faster than either the standard iPhone wall adapter or the wireless charging pads.JUMP TO ENDPAGE 7 OF 8

Some years ago, Apple acquired a reputation among tech enthusiasts, consumers, and business analysts alike for conjuring entire new product categories and frontiers. This was mostly mythology; Apple has rarely introduced products or features that were completely unprecedented. But don’t take that as criticism. The reality is more relevant to the user.

The company’s best products have taken existing innovations and refined them for mass adoption or combined them in new, synergistic configurations that allowed emerging categories to overcome limitations endemic in previous attempts. To this end, the iPhone X does three major things of note, just like the first iPhone did 10 years ago.

First, the iPhone X adopts the more natural OLED and HDR screen technologies and places them in a screen format that, despite the notch, generally succeeds at reducing barriers to our relationship with digital content and functions.

Second, the iPhone X takes the facial recognition that other phones have tried out, plus the promising-but-not-quite-there concept behind Microsoft’s vibrant but short-lived Kinect experiment, and lays the groundwork for myriad new ways to interact with our devices, from frivolous social features to profound security implications.

Third, the iPhone X combines a robust suite of sensors, good cameras, exceptional mobile performance, and mature software to deliver the first great, viable, mass-market AR platform. This may very well break the levies for a flood of innovative applications, changing the way the physical world and the digital layer we’ve built for it relate to one another.

Author William Gibson once said, albeit with a very different meaning, “The future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed.” Every individual component of the iPhone X's version of the future has been seeping into the recent past here and there. But this future can’t actualize unless the components work well, individually and together, all in one device.

The original iPhone made the future happen by the same approach a decade ago, and the iPhone X does it again. Of course this phone is not as revolutionary as the first iPhone was—starting a new chapter is never going to be as big a deal as opening a new book. And there are reservations around battery life, durability, and first-generation Face ID usability. As always, the second iteration of a new design will surely be more refined, and cautious buyers who wait for year two will probably be rewarded for their patience. But the iPhone X is nevertheless easy to recommend if you want a glimpse at what's going to be exciting in the next 10 years.

SAMUEL AXONBased in Los Angeles, Samuel is the Senior Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he covers Apple products, display technology, internal PC hardware, and more. He is a reformed media executive who has been writing about technology for 10 years at Ars Technica, Engadget, Mashable, PC World, and many others.