{

"cells": [

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"# Getting started with data analysis"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"## What is pandas?\n",

"\n",

"The [`pandas` Python library](https://pandas.pydata.org/) [^pandas] is an easy-to-use, powerful data analysis toolkit. It is a mature data analytics framework that is widely used in different fields of science. The development of `pandas` started in 2008 and it is now maintained by an active developer community ({cite}`McKinney2022`).\n",

"\n",

"`pandas` is a \"high-level\" package, which means that it makes use of several other packages in the background. It combines the performance of powerful Python libraries such as [NumPy](https://numpy.org/) [^numpy], [Matplotlib](https://matplotlib.org/) [^matplotlib], and [SciPy](https://scipy.org/) [^scipy].\n",

"\n",

"One of the most useful features of `pandas` is its ability to interact with numerous data formats. It supports reading and writing data from/to formats including\n",

"\n",

"- CSV\n",

"- JSON\n",

"- HTML\n",

"- MS Excel\n",

"- HDF5\n",

"- Stata\n",

"- SAS\n",

"- Python Pickle format\n",

"- SQL (Postgresql, MySQL, Oracle, MariaDB, etc.)\n",

"\n",

"For a full list of supported file formats and other features, please refer to the official [`pandas` documentation and reference guide](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/) [^pandasdocs]."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

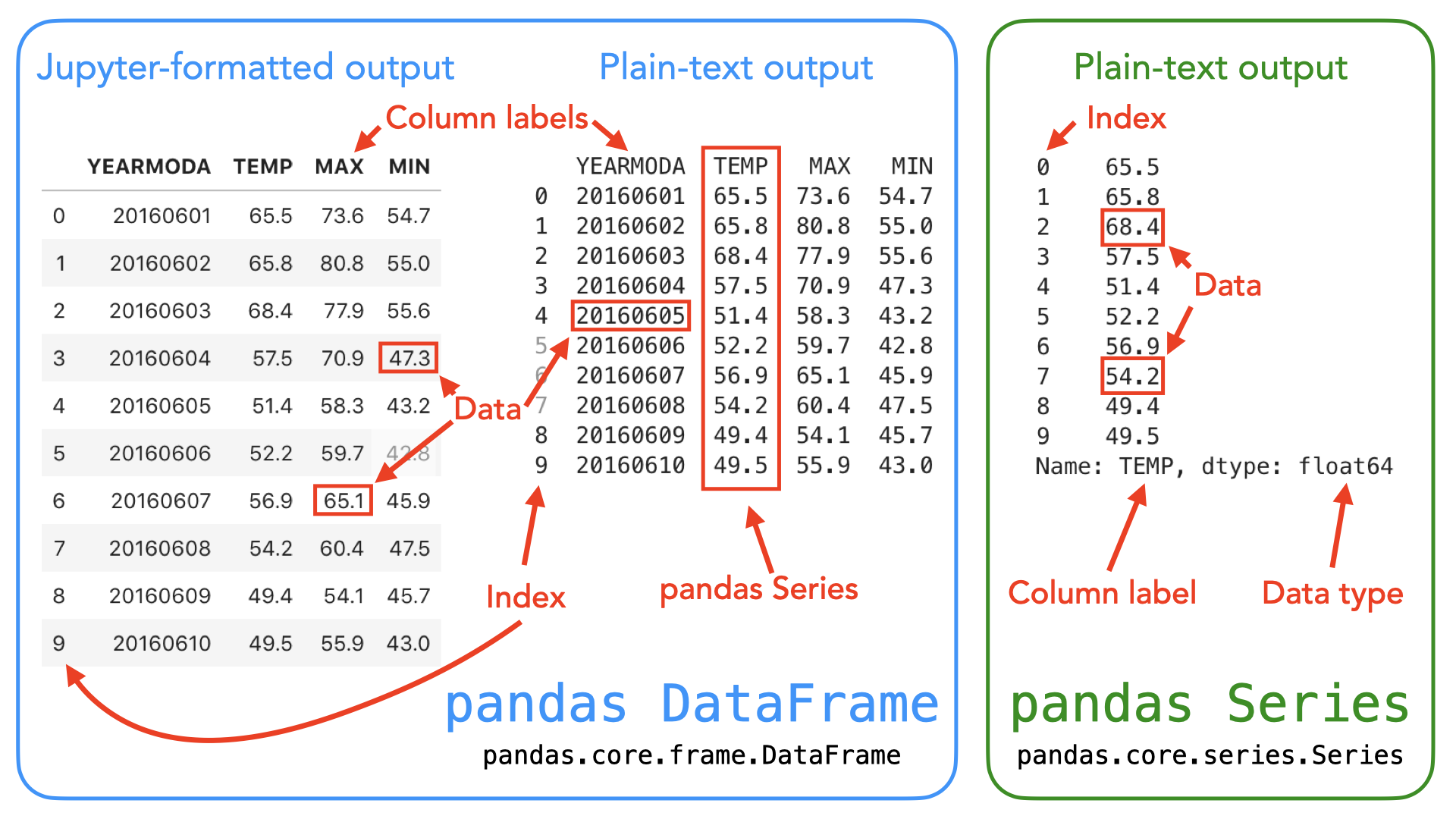

"## pandas data structures\n",

"\n",

"In `pandas`, table-like data are stored in two-dimensional `DataFrame` objects with labeled rows and columns. The `pandas` `DataFrame` was originally inspired by data frames that are in the R programming language. You can think of a `DataFrame` in `pandas` as a programmable spreadsheet. One-dimensional sequences of values are stored as a `pandas` `Series`. A single row or column in a `pandas` `DataFrame` is actually a `pandas` `Series`. You can think of a `pandas` `Series` as a clever list. These `pandas` structures incorporate a number of things we've already encountered earlier in this book, such as indices, data stored in a collection, and data types.\n",

"\n",

"\n",

"\n",

"_**Figure 3.1**. Illustration of the `pandas` `DataFrame` and `Series` data structures. A `pandas` `DataFrame` is a two-dimensional data structure used for storing and manipulating table-like data (data with rows and columns). A `pandas` `Series` is a one-dimensional data structure used for storing and manipulating a sequence of values._\n",

"\n",

"As you can see from Figure 3.1, both the `DataFrame` and `Series` in `pandas` have an index that can be used to select values, but `DataFrame` objects also have labels to identify columns. In the following sections, we will use many of these features to explore real-world data and learn some handy data analysis procedures using `pandas`. For a comprehensive overview of `pandas` data structures, we recommend you have a look at the [`pandas` online documentation about data structures](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/dsintro.html) [^pandas_ds] as well as Chapter 5 in {cite}`McKinney2022`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"## Reading tabular data \n",

"\n",

"In the following sections, we will learn how to read data from a text file (`data/kumpula-summer-2024.txt`), which contains weather observations from the Kumpula neighborhood in Helsinki, Finland. The data were retrieved from [Finnish Meteorlogical Institute's data service](https://en.ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/download-observations/) [^fmi] and it contains observed daily temperatures recorded at two times during the day (`TEMP1`: 10 a.m.; `TEMP2`: 2:00 p.m.), as well as the minimum and maximum temperatures from Summer 2024 (June 1st - August 31st, 2024) recorded by the Kumpula weather observation station in Helsinki. The file includes 92 rows of observations (one per day). The first fifteen rows in the file look like the following:\n",

"\n",

"```\n",

"# Data file contents: Daily temperatures (TEMP1 (10AM), TEMP2 (4PM), min, ma...\n",

"# for June 1 - August 31, 2024\n",

"# Data source: Finnish Meteorological Institute - downloaded from open data ...\n",

"# Data processing: Extracted temperatures from raw data file, converted to\n",

"# comma-separated format - Extracted TEMP1 and TEMP2 and created YEARMODA co...\n",

"#\n",

"# Processed by Kamyar Hasanzadeh 15.09.2024\n",

"\n",

"YEARMODA,MAX,MIN,TEMP1,TEMP2\n",

"20240601,26.2,18.4,24.2,23.2\n",

"20240602,24.4,17.1,20.7,24.2\n",

"20240603,25.7,15.2,22.5,23.1\n",

"20240604,24.6,15.7,19.3,24.6\n",

"20240605,23.4,12.8,20.3,23.2\n",

"20240606,19.3,13.6,19.2,14.9\n",

"```\n",

"\n",

"Now that we have familiarized ourselves with the data, we can continue and see how to read the data using `pandas`. Let's start by importing the `pandas` module. It is customary to import `pandas` as `pd`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Next, we will read the input data file and store the contents of that file into a variable called `data` using the `.read_csv()` function."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

},

"lines_to_next_cell": 2

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Our input file is a comma-delimited file, meaning that the columns in the data are separated by commas (`,`) on each row. The `.read_csv()` function uses comma as the default delimiter, hence we did not need to specify it separately in the command above. If all went as planned, you should now have a new variable `data` in memory that contains the input data. \n",

"\n",

"It is quite common to have some other character instead of a comma separating the columns from each other. The `.read_csv()` in pandas is a generic function for reading text-based data files, supporting files separated by commas, spaces, or other common separators. The `sep` parameter can be used to specify which character is used as a delimiter. For instance `sep=';'`, would be used when the columns in the data file are delimited with a semicolon (`;`). For a full list of available parameters for the `read_csv()` function, please refer to the [pandas `.read_csv()` documention](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/reference/api/pandas.read_csv.html) [^readcsv] or run `help(pd.read_csv)`. \n",

"\n",

"Pandas has several other functions for parsing input data from different file formats. For example, reading Excel files can be easily done using the `.read_excel()` function. Another useful function is `.read_pickle()`, which reads data stored in the Python pickle format. Check out the [pandas documentation about input and output tools](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/io.html) [^pandas_io] for more details about reading data."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Let's check the the contents of our data. You can print the contents of a `DataFrame` (or a snippet of it) simply by calling it by name (e.g., `data`). However, quite often you want to check only a selection of *n* rows from the start or end of the data set. For doing that, we can use the `.head()` method of the `DataFrame` object that will, by default, return the first five rows of the `DataFrame`. You can return any number of rows by adding that number inside the parentheses. For example, `data.head(10)` would return the first ten rows from the `DataFrame` called `data`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Similarly, `.tail()` will return the last rows of the `DataFrame` (last five rows by default)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Looking at the output from `data.head()` we can see that the first lines of the `DataFrame` look a bit weird. Several columns contain rows with `NaN` values. `NaN` stands for \"not a number\", and might indicate some problem with reading in the contents of the file. Plus, we expected 92 lines of data, but the index values go up to 98 when we print the last rows of the `data` variable. Looks like we need to investigate this further."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"As we can observe, there are some metadata at the top of the file giving basic information about its contents and source. This is not data we want to process, so we need to skip over that part of the file when we read it. Here are the 8 first rows of data in the text file (note that the 8th row is blank)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"```\n",

"# Data file contents: Daily temperatures (TEMP1 (10AM), TEMP2 (4PM), min, ma...\n",

"# for June 1 - August 31, 2024\n",

"# Data source: Finnish Meteorological Institute - downloaded from open data ...\n",

"# Data processing: Extracted temperatures from raw data file, converted to\n",

"# comma-separated format - Extracted TEMP1 and TEMP2 and created YEARMODA co...\n",

"#\n",

"# Processed by Kamyar Hasanzadeh 15.09.2024\n",

"\n",

"```"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Fortunately, skipping over rows is easy to do when reading data with `pandas`. We just need to add the `skiprows` parameter when we read the file, listing the number of rows to skip (eight in this case). Let's try reading the data file again, this time including the `skiprows` parameter."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

},

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"Let's see what the data looks like now."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

},

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"Looks good! We seem to have 92 rows of data (index running from 0 to 91), and meaningful column names and values.\n",

"\n",

"Note that a `pandas` `DataFrame` has labeled axes (rows and columns). In our sample data, the rows are labeled with an index value (`0` to `91`), and columns labeled `YEARMODA`, `MAX`, `MIN`, `TEMP1`, and `TEMP2`. Later on, we will learn how to use these labels for selecting and updating subsets of the data. "

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"It is also possible to read only specific columns from the data when using the `.read_csv()` function. You can achieve this using the `usecols` parameter when reading the file which accepts a list of column names that will be included in the resulting `DataFrame`. In addition, columns can be selected using positional indices (e.g., `[0, 1]`) corresponding the position of the column in the file that specify which columns should be read. For additional details, see the [pandas `.read_csv()` documentation](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/reference/api/pandas.read_csv.html)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"question"

]

},

"source": [

"#### Question 3.1\n",

"\n",

"How would you read the file `kumpula-summer-2024.txt` in once again selecting only the `YEARMODA` and `TEMP1` columns? Try reading the file into a new variable called `temp_data` and only selecting two columns. The new variable `temp_data` should have 92 rows and 2 columns."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"remove_cell"

]

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# Use this cell to enter your solution.\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"Using the `usecols` parameter to limit the number of columns can be useful when working with data files that have possibly tens or even hundreds of columns. Typically you are not interested in all of them, but you want focus on only a few important ones which you can select already when reading the data. "

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"## Writing data to a file\n",

"\n",

"Naturally, it is also possible to write the data from `pandas` to a file. `pandas` supports many common output formats such as CSV files, MS Excel, xml and more. For full details about supported file formats and writer functions, see the [pandas i/o documentation](https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/io.html) [^pandas_io]. As an example, let's write the data from the `kumpula-summer-2024.txt` file to a csv-file called `kumpula_temp_results_summer_2024.csv` using the `.to_csv()` method."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

},

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# define output filename\n",

"output_fp = \"kumpula_temp_results_summer_2024.csv\"\n",

"\n",

"# Save DataFrame to csv\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

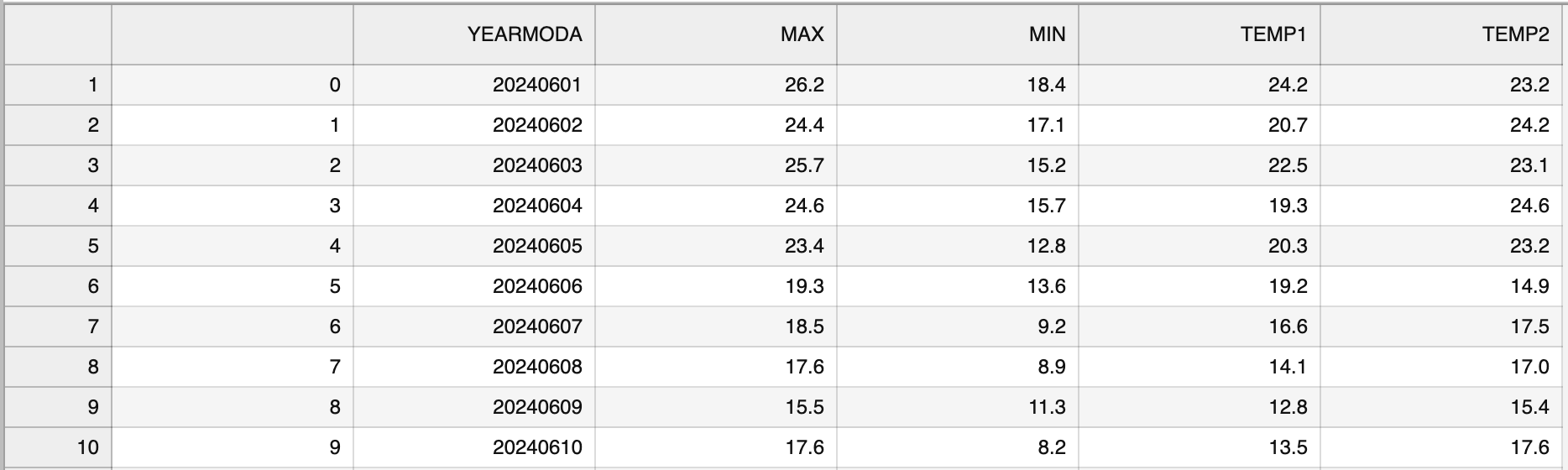

"\n",

"\n",

"_**Figure 3.2**. The output CSV file opened in JupyterLab._\n",

"\n",

"Figure 3.2 shows the content of the output file. As we can see, the first column contains the index value without any column name. Also the temperature values are represented as floating point number with a precision of one decimal place.\n",

"\n",

"Let's see how we can modify some aspects of the output file using `pandas` and save the data again without the index, and with zero decimals. Omitting the index can be achieved using the `index=False` parameter. Decimal precision can be specified using the `float_format` parameter. The format text `float_format=\"%.0f\"` will set decimal precision to zero (i.e., integer values), while `\"%.2f\"` would set the precision to two decimal places, for example."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# define output filename\n",

"output_fp2 = \"kumpula_temp_results_integers_summer_2024.csv\"\n",

"\n",

"# Save dataframe to csv\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true

},

"source": [

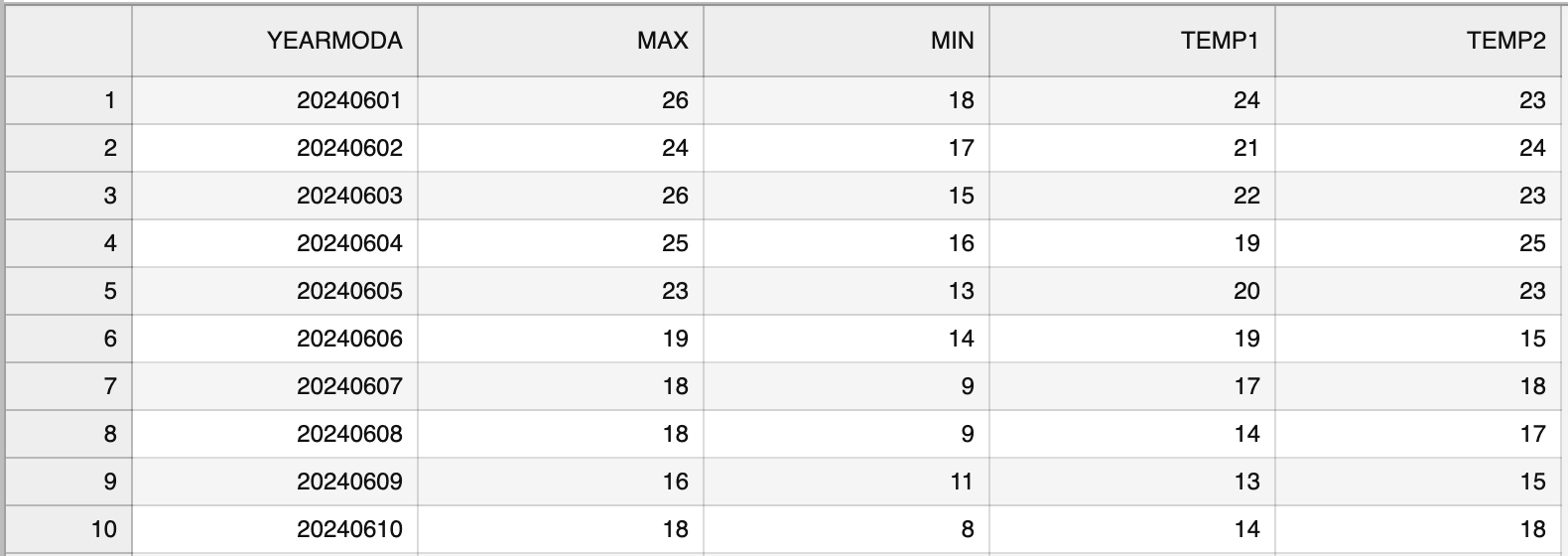

"\n",

"\n",

"_**Figure 3.3**. The formatted output CSV file opened in JupyterLab._\n",

"\n",

"Figure 3.3 shows the \"cleaner\" output file that lacks the index column and has the temperature values rounded to integers."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"## DataFrame properties\n",

"\n",

"Now we will continue exploring the data set we have stored in the variable `data`. A normal first step when you load new data is to explore the data set a bit to understand how the data is structured, and what kind of values are stored in in. Let's start by checking the size of our `DataFrame`. We can use the `len()` function similar to the use with lists to see how many rows we have."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"We can also get a quick sense of the size of the data set using the attribute `.shape`. It returns a `tuple` with the number of rows as the first element and the number of columns as the second element."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Here we see that our data set has 92 rows and 5 columns, just as we saw above when printing out the entire `DataFrame`. Note that we do not use parentheses after the word `shape` when accessing attributes. `.shape` is one of several attributes related to a `pandas` `DataFrame` object. Attributes are typically used to store useful information (or *metadata*) about the object at hand. We will see many more examples of attributes throughout this book."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Let's also check the column names we have in our `DataFrame` (yes, this is an attribute as well!). We already saw the column names when we checked the 5 first rows using `data.head()`, but often it is useful to access the column names directly. You can check the column names using the `.columns` attribute, which returns an index object that contains the column labels. Alternatively, we can add the `.values` attribute to get an array of the column names. For example, we could check the column names by typing `data.columns.values`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"We can also find information about the row identifiers using the `.index` attribute."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Here we see how the data is indexed, starting at `0`, ending at `92`, and with an increment of 1 between each value. This is basically the same way in which Python lists are indexed, however, `pandas` allows also other ways of identifying the rows. `DataFrame` indices could, for example, be character strings or date objects. We will learn more about resetting the index later. What about the data types of each column in our `DataFrame`? We can check the data type of all columns at once using the `.dtypes` attribute."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# Print data types\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"lines_to_next_cell": 2

},

"source": [

"Here we see that `YEARMODA` is contains integer values with 64-bit precision (`int64`), while the other columns contain decimal values with 64-bit precision (`float64`)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"question"

]

},

"source": [

"#### Question 3.2\n",

"\n",

"How would you print out the number of columns in our `DataFrame`?"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"remove_cell"

]

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# Use this cell to enter your solution.\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"## Selecting columns"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"When performing data analysis, it is very common that you want to select certain columns from the data for further processing. We can select specific columns based on the column names, for example. The basic syntax is `DataFrame[value]`, where `value` can be a single column name as a character string, or a list of column names. Let's start by selecting two columns: `\"YEARMODA\"` and `\"MAX\"`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Let's also check the data type of this selection."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"As we can see, the subset is still a `pandas` `DataFrame`, and we are thus able to use all the related methods and attributes with this subset. For example, we can check the shape."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"We can also access a single column of the data using on the column name."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"What about the type of the column itself?"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Each column (and each row) in a `pandas` `DataFrame` is indeed a `pandas` `Series`. Notice that you can also retrieve a column using a different syntax. For example, we can access the `MAX` column using `data.MAX`. This syntax works only if the column name is a valid name for a Python variable (e.g., the column name should not contain whitespace). The syntax `data[\"column\"]` works for all column names, so we recommend using this approach."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"## Unique values\n",

"\n",

"Sometimes it is useful to extract the unique values that you have in your column. We can do that by using `.unique()` method."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"As a result we get an array of unique values in that column. In the case of temperatures, this might not be that interesting, but in other cases this can be more useful. We can also directly access the number of unique values using the `.nunique()` method."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"## Descriptive statistics"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"The `DataFrame` and `Series` data types in `pandas` contain useful methods for getting summary statistics. Available methods include `.mean()`, `.median()`, `.min()`, `.max()`, and `.std()` (the standard deviation). The statistics can be calculated for a single column (i.e., a `Series`) or for all columns at once for the entire `DataFrame`. To check the maximum temperature in our `DataFrame` (i.e., a single column or `Series`), we can do following:"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"The output in this case will be a single floating point number presenting the mean maximum daily temperature, 22.05 degrees Celsius. To get the mean statistic for all columns in the `DataFrame`, we can use `.mean()` in a similar manner but without specifying the column name."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Notice that in this case, the result is a `Series` showing the mean values for each column. For an overview of the basic statistics for all attributes in the data, we can use the `.describe()` method."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"As a result, we get the number of values that are not None for each column (`count`) as well as the basic statistics and quartiles (min, 25%, 50%, 75%, and max)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"question"

]

},

"source": [

"#### Question 3.3\n",

"\n",

"It doesn’t make much sense to print out descriptive statistics for the dates contained in the `YEARMODA` column. See if you can print out the descriptive statistics again, but only for columns `TEMP1`, `TEMP2`, `MAX`, and `MIN`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": [

"remove_cell"

]

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"# Use this cell to enter your solution.\n"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"It is also possible to get other `DataFrame`-specific information such as the index, columns and data types, non-null values, and memory usage by calling `.info()`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"outputs": [],

"source": []

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"## Other ways of constructing pandas objects (*optional*)\n",

"\n",

"Most often we create `pandas` objects by reading in data from an external source such as a text file. However, there are other ways to convert data stored in other Python data types to `pandas` objects. Here, we show how to create `pandas` objects from a Python `list` or `dictionary` object.\n",

"\n",

"If you have a very long `list` of values, creating a `pandas` `Series` (or `numpy.array`) will allow you to interact with these data more efficiently in terms of computing time. This is how you can create a `pandas` `Series` from a `list`."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {

"collapsed": false,

"deletable": true,

"editable": true,

"jupyter": {

"outputs_hidden": false

}

},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"number_list = [4, 5, 6, 7.0]\n",

"number_series = pd.Series(number_list)\n",

"print(number_series)"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"deletable": true,

"editable": true

},

"source": [

"Note that `pandas` is smart about the conversion, detecting a single floating point value (`7.0`) and assigning all values in the `Series` the data type `float64`. If needed, you can also create a custom index when creating the object."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"number_list = [4, 5, 6, 7.0]\n",

"index_list = [\"a\", \"b\", \"c\", \"d\"]\n",

"number_series = pd.Series(number_list, index=index_list)\n",

"print(number_series)"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"type(number_series)"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"What about combining several lists to construct a `DataFrame` from them? No problem. Let's see how we can convert several lists into a `pandas` `DataFrame`. Let's first create a few lists with the same number of items in each."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"stations = [\"Hanko\", \"Heinola\", \"Kaisaniemi\", \"Malmi\"]\n",

"latitudes = [59.77, 61.2, 60.18, 60.25]\n",

"longitudes = [22.95, 26.05, 24.94, 25.05]"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Now we can create a `pandas` `DataFrame` by using the `pandas.DataFrame()` constructor and passing a Python `dictionary` (e.g., `{\"column_1\": list_1, \"column_2\": list_2, ...}`) to it, showing the structure of our data."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"new_data = pd.DataFrame(data={\"station\": stations, \"lat\": latitudes, \"lon\": longitudes})\n",

"new_data"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"It is also possible to create a `pandas` `DataFrame` from a list of dictionaries. This approach is quite similar as the previous example, but we will organize the data a bit differently. Having a list of dictionaries is common if you happen to work with `JSON` files, which are commonly used when reading data from the web (e.g., via an *{term}`Application Programming Interface`*)."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"dictionaries = [\n",

" {\"station\": \"Hanko\", \"lat\": 59.77, \"lon\": 22.95},\n",

" {\"station\": \"Heinola\", \"lat\": 61.2, \"lon\": 26.05},\n",

" {\"station\": \"Kaisaniemi\", \"lat\": 60.18, \"lon\": 24.94},\n",

" {\"station\": \"Malmi\", \"lat\": 60.25, \"lon\": 25.05},\n",

"]\n",

"\n",

"# Pass the list into the DataFrame constructor\n",

"new_data_2 = pd.DataFrame(dictionaries)\n",

"new_data_2"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"As a result, we create a `DataFrame` that is identical to our first example above.\n",

"\n",

"Finally, sometimes you might start working with an empty `DataFrame` and only later \"populate\" it with new columns."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"df = pd.DataFrame()\n",

"print(df)"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {},

"source": [

"Now we have an empty `DataFrame`, and we can add new columns to it based on the lists we created earlier. Notice that the following approach requires that the length of all the lists that you want to add are equal."

]

},

{

"cell_type": "code",

"execution_count": null,

"metadata": {},

"outputs": [],

"source": [

"df[\"lon\"] = longitudes\n",

"df[\"lat\"] = latitudes\n",

"df"

]

},

{

"cell_type": "markdown",

"metadata": {

"editable": true,

"slideshow": {

"slide_type": ""

},

"tags": []

},

"source": [

"## Footnotes\n",

"\n",

"[^pandas]: \n",

"[^numpy]: \n",

"[^matplotlib]: \n",

"[^scipy]: \n",

"[^pandasdocs]: \n",

"[^pandas_ds]: \n",

"[^fmi]: \n",

"[^readcsv]: \n",

"[^pandas_io]: \n"

]

}

],

"metadata": {

"anaconda-cloud": {},

"kernelspec": {

"display_name": "Python 3 (ipykernel)",

"language": "python",

"name": "python3"

},

"language_info": {

"codemirror_mode": {

"name": "ipython",

"version": 3

},

"file_extension": ".py",

"mimetype": "text/x-python",

"name": "python",

"nbconvert_exporter": "python",

"pygments_lexer": "ipython3",

"version": "3.11.6"

}

},

"nbformat": 4,

"nbformat_minor": 4

}