At this stage, we should expect that the complex numbers will be our atoms, and we'll form a composite out of them. What are these composites? You've probably heard of them before: they are polynomials. Indeed, we will now take for our composites "equations" themselves.

Recall that a polynomial is defined quite like a "base-n" number, but what before was the "base" is now a variable. The $c_{n}$ are generally complex coefficients.

$ f(z) = \dots + c_{4}z^{4} + c_{3}z^{3} + c_{2}z^{2} + c_{1}z + c_{0} $

Two important things we can do to polynomials are differentiate and integrate them.

For instance, $\frac{d}{dz} x^{2} = 2x$. And inversely: $\int 2x dx = x^{2} + C$, where we also add a constant C, since when we differentiate it, it will go to zero (so we can't rule out it's not there).

We can have polynomials with a finite number of terms, but we could also have infinite polynomials. Here's an interesting fact.

The meaning of the derivative of a function $\frac{d}{dx} f(x)$ is the change with regard to x at the input value. For a real valued function, you can imagine it like the slope of the line tangent to the curve at that point. You can imagine choosing two points on the curve, and bringing them infinitesimally close together, so that you get a linear approximation to the curve at that point. Inversely, integration is like summing the area under a curve with little rectangles, and imagining shrinking the size of the rectangles to be infinitesimally small.

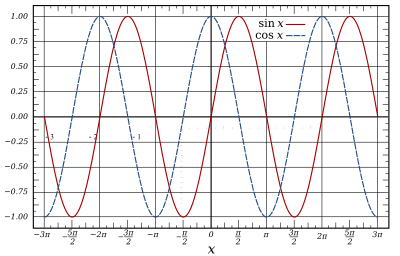

Check out this image of $sin(x)$ and $cos(x)$:

It happens that $\frac{d}{dx} sin(x) = cos(x)$ and $\frac{d}{dx} cos(x) = -sin(x)$. You can see this visually. When sine is at its peak, its tangent line is a horizontal line: $\frac{\Delta rise}{\Delta run} = \frac{0}{1}$. And behold: cosine is 0 there! And when cosine has a peak, sine is 0! And this holds the whole way through.

Notice $\frac{d}{dx} sin(x) = cos(x) \rightarrow \frac{d}{dx} cos(x) = -sin(x) \rightarrow \frac{d}{dx} -sin(x) = -cos(x) \rightarrow \frac{d}{dx} -cos(x) = sin(x)$, and we come full circle. Whereas a finite dimensional polynomial will eventually give you 0 if you differentiate it enough times, an "infinite dimensional polynomial" can be differentiated an infinite number of times.

It is a nice theorem that infinitely differentiable functions can be expressed as "Taylor polynomials":

$f_{a}(x) = f(a) + \frac{f^{\prime}(a)}{1!}(x-a) + \frac{f^{\prime\prime}(a)}{2!}(x-a)^{2} + \frac{f^{\prime\prime\prime}(a)}{3!}(x-a)^{3} + \dots$, where $n! = n(n-1)(n-2)\dots (1)$ and $f^{(n)}$ means take the $n^{th}$ derivative.

In other words, $f_{a}(x) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{f^{(n)}(a)}{n!}(x-a)^{n}$.

In the case of sine and cosine (evaluated at 0):

$sin(x) = sin(0) + \frac{cos(0)}{1!}x - \frac{1}{2!}sin(0)x^{2} - \frac{1}{3!}cos(0)x^{3} + \frac{1}{4!}sin(0)x^{4} + \dots$

$cos(x) = cos(0) - \frac{sin(0)}{1!}x - \frac{1}{2!}cos(0)x^{2} + \frac{1}{3!}sin(0)x^{3} + \frac{1}{4!}cos(0)x^{4} + \dots$

But since $sin(0) = 0$ and $cos(0) = 1$, these are just:

$sin(x) = x - \frac{x^{3}}{3!} + \frac{x^{5}}{5!} - \dots = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n}x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!}$

$cos(x) = 1 - \frac{x^{2}}{2!} + \frac{x^{4}}{4!} - \dots = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n}x^{2n}}{(2n)!}$

So now we can approximate sine and cosines by evaluating the terms of this series! They are "transcendental" functions in the sense that they aren't equal to any finite polynomial: they can only be reached with an infinite amount of algebra!

You may know that the exponential function is the magical function which is own derivative:

$\frac{d}{dx} e^{x} = e^{x}$. Since $e^{0} = 1$, $e^{x} = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{n}}{n!} = \frac{1}{0!} + \frac{x}{1!} + \frac{x^{2}}{2!} + \frac{x^{3}}{3!} + \frac{x^{4}}{4!}\dots$.

We then work out the series for $e^{ix} = \frac{1}{0!} + i\frac{x}{1!} - \frac{x^{2}}{2!} - i\frac{x^{3}}{3!} + \frac{x^{4}}{4!} + \dots$.

Rearranging things we have: $ e^{ix} = \Big{(} 1 - \frac{x^{2}}{2!} + \frac{x^{4}}{4!} + \dots \Big{)} + i\Big{(} x - \frac{x^{3}}{3!} + \frac{1}{5!}x^{5} + \dots \Big{)}$. In other words: $e^{ix} = cos(x) + isin(x)$, as we promised before. As you wind around the unit circle, the x-coordinate traces out $cos(x)$ and the y-coordinate traces out $sin(x)$.

For now, however, let's consider finite polynomials. They are their own Taylor polynomials.

A classic problem is to solve for the "roots" of $f(z)$. These are the values of $z$ that make $f(z) = 0$.

The degree of a polynomial is the highest power of the variable that appears within it. It turns out that a degree $n$ polynomial has exactly $n$ complex roots. A polynomial can therefore be factored into roots, just as a whole number can be factored into primes.

$ f(z) = \dots + c_{4}z^{4} + c_{3}z^{3} + c_{2}z^{2} + c_{1}z + c_{0} = (z - \alpha_{0})(z - \alpha_{1})(z - \alpha_{2})\dots $

The only catch is that the roots of the polynomial $f(z)$ are left invariant if you multiply the whole polynomial by any complex number. So the roots define the polynomial up to multiplication by a complex "scalar." (By the way, you can think about infinite dimesional polynomials as being determined by their infinite roots using something called the Weierstrass Factorization Theorem.)

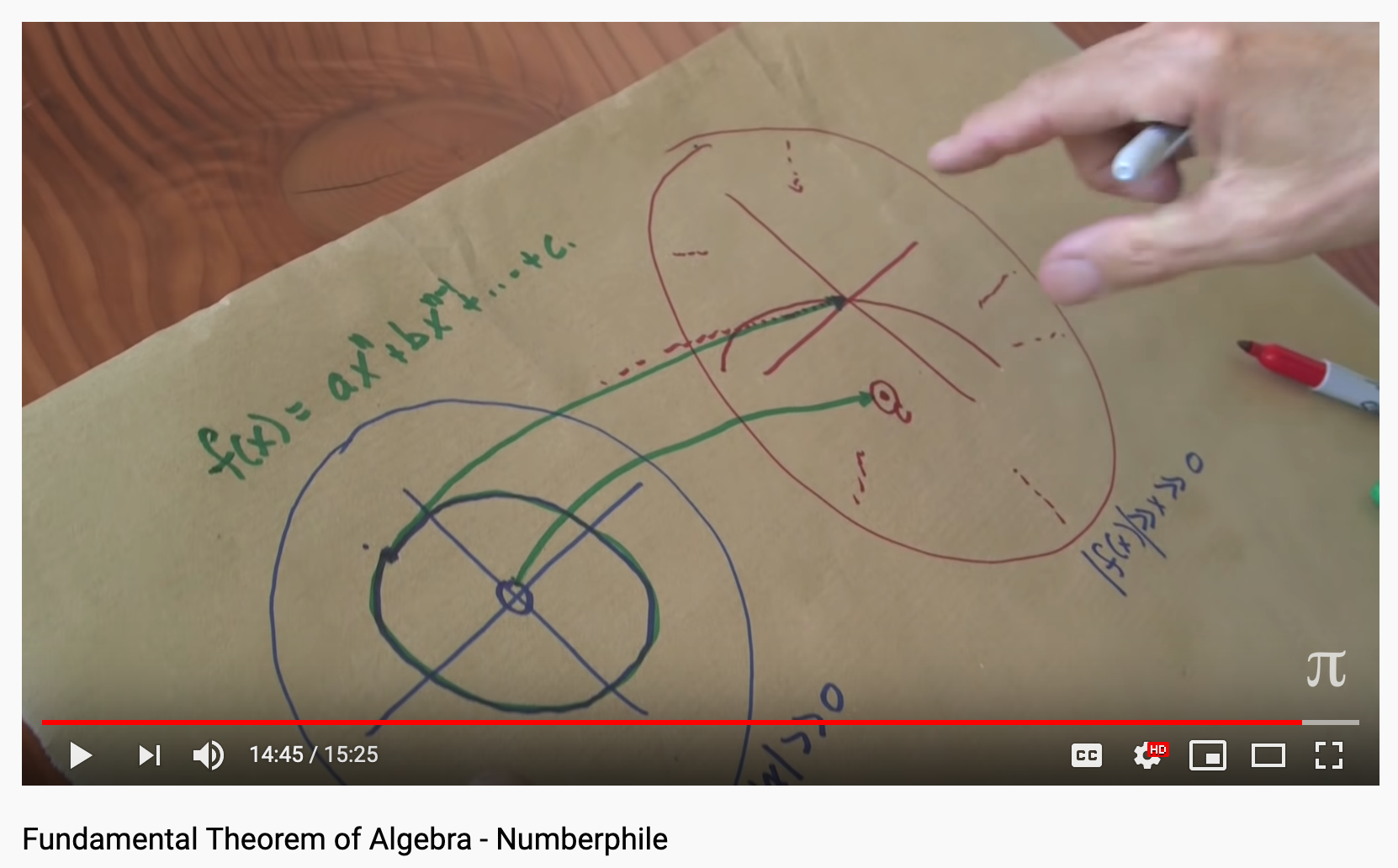

The proof of this is called the fundamental theorem of algebra, just as the proof that whole numbers can be uniquely decomposed into primes is called the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Interestingly, the proof doesn't require much more than some geometry. Here's a brief sketch. First it's worth recalling that: for some complex $z = re^{i\theta}$, then $z^{n} = r^{n}e^{in\theta}$.

So suppose we have some polynomial $ f(z) = c_{n}z^n + \dots + c_{4}z^{4} + c_{3}z^{3} + c_{2}z^{2} + c_{1}z + c_{0}$. Now suppose that we take $z$ to be very large. For a very large $z$ the difference between $z^{n-1}$ and $z^n$ is considerable, and we can say that the polynomial is dominated by the $c_{n}z^n$ term. Now imagine tracing out a big circle in the complex plane corresponding to different values of $z$. If we look at $f(z)$, it'll similarly wind around a circle $n$ times as fast (with a little wiggling as it does so corresponding to the other tiny terms). Now imagine shrinking the $z$ circle down smaller and smaller until $z=0$. But $f(z=0) = c_{0}$, which is just the constant term. So as the "input" circle shrinks down to 0, the "output" circle shrinks down to $c_{0}$. To get there, however, the shrinking circle in the output plane must have passed the origin at some point, and therefore the polynomial has at least one root. You factor that root out of the polynomial leading to a polynomial of one less degree, and repeat the argument, until there are no more roots left. Therefore, a degree $n$ polynomial has exactly $n$ roots in the complex numbers.

This is related to the fact that the complex numbers represent the algebraic closure of the elementary operations of arithmetic. One could consider other number fields: the real numbers, for instance: and then there might not be exactly $n$ roots for a degree $n$ polynomial.

It's worth noting "Vieta's formulas" which relate the roots to the coefficients:

Given a polynomial $f(z) = c_{n}z^n + \dots + c_{4}z^{4} + c_{3}z^{3} + c_{2}z^{2} + c_{1}z + c_{0} = (z - \alpha_{0})(z - \alpha_{1})(z - \alpha_{2})\dots(z - \alpha_{n-1}) $, we find:

$ 1 = \frac{c_{n}}{c_{n}}$

$ \alpha_{0} + \alpha_{1} + \alpha_{2} + \dots + \alpha_{n-1} = -\frac{c_{n-1}}{c_{n}}$

$ \alpha_{0}\alpha_{1} + \alpha_{0}\alpha_{2} + \dots + \alpha_{1}\alpha_{2} + \dots + \alpha_{2}\alpha_{3} \dots = \frac{c_{n-2}}{c_{n}}$

$ \alpha_{0}\alpha_{1}\alpha_{2} + \alpha_{0}\alpha_{1}\alpha_{3} + \dots + \alpha_{1}\alpha_{2}\alpha_{3} + \dots + \alpha_{2}\alpha_{3}\alpha_{4} \dots = - \frac{c_{n-3}}{c_{n}}$

$ \vdots $

$ \alpha_{0}\alpha_{1}\alpha_{2}\dots = (-1)^{n}\frac{c_{0}}{c_{n}} $

In other words, the $c_{n-1}$ coefficient is the sum of roots taken one at a time times $(-1)^{1}$, the $c_{n-2}$ coefficient is given by the sum of the roots taken two at a time times $(-1)^{2}$, and so on, until the constant term is given by the product of the roots times $(-1)^{n}$, in other words the $n$ roots taken all at a time. We divide out by $c_{n}$ as the roots are defined up to multiplication by a complex sclar.

In other words, the relationship between coefficients and roots is "holistic"--just like the relationship between a composite whole number and its prime factors, the latter of which are contained "unordered" within it. Each of the coefficients depends on all the roots. Moreover, by taking the roots 0 at a time, 1 at a time, 2 at a time, etc, we get an ordered representation from an unordered one.

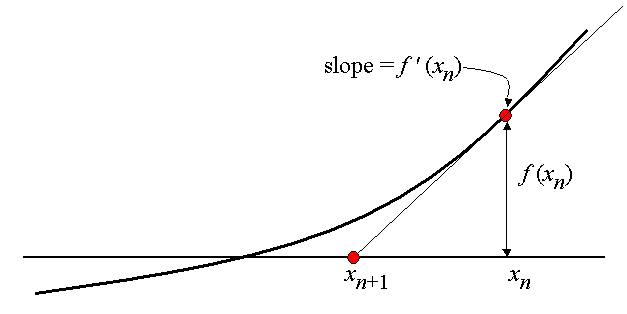

If you want to find some roots, you could try like Renaissance Italian mathematicians to do so in public contests for popular acclaim. Or you could try to approximate them. For example, try Newton's method, given some starting guess $g_{0}$:

$g_{n+1} = g_{n} - \frac{f(g_{n})}{f^{\prime}(g_{n})}$

On the other hand, we're familiar with the quadratic equation:

$ r = -b \pm \frac{\sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a}$

Given a polynomial $az^2 + bz + c = 0$, we can plug in the coefficients, and evaluating the algebra, we compute the roots directly. Is there always such an equation? It turns out no! Well, actually, in the case of polynomials of degree 1, 2, 3, 4, there is such a "closed" expression. But in general polynomials of degree 5 or higher won't have such a closed expression that delivers the roots directly from the coefficients. This is the famous result of Galois theory, developed in the early 19th century by Evariste Galois.

In proving this theorem, Galois had to invent the idea of a symmetry group.

You can think of a symmetry group like a set of "actions" that you can do that leave some object invariant. In this way, we can define an object in terms of all the things that can be done to it which leave it the same: all the things that can be done that can be undone.

These "action" are called elements of the symmetry group: $a, b, c \in G$. The rules are that if you "multiply" $ab = c$, you always get another element of the symmetry group. Moreover there is an identity element such that $1a = a$, and every element has an inverse element such that $aa^{-1} = 1$. And finally, there's associativity: $(ab)c = a(bc)$.

We've already seen some groups. Consider:

$ a + b = c $

$ 0 + a = a $

$ a + -a = 0 $

$ (a + b) + c = a + (b + c)$

The integers form a symmetry group where the "action" is addition.

$ a \times b = c$

$ 1 \times a = a$

$ a \times \frac{1}{a} = 1$

$ (a \times b) \times c = a \times (b \times c)$

The rational form a symmetry group where the action is multiplication.

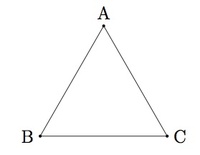

These two groups both have a countably infinite number of elements. There are also groups with only a finite number of elements, like the group formed from permutations of a set, like the group of discrete symmetries of an equilateral triangle: do nothing, turn 1/3 of the way, turn 2/3 of the way, flip across A, flip across B, flip across C.

$ABC \rightarrow ABC$

$ABC \rightarrow BCA$

$ABC \rightarrow CAB$

$ABC \rightarrow ACB$

$ABC \rightarrow CBA$

$ABC \rightarrow BAC$

Notice that these are also all the permutations of 3 symbols.

You can also have continuous symmetry groups, with an uncountable number of elements, where between any two group elements, there is a third element: like the group of rotations of the sphere. These are called Lie groups.

Now there is an atomic principle at work with regard to groups. Groups can be decomposed into subgroups, and you can decompose the subgroups into subgroups until you can't any more: and those are the simple groups.

For example, the triangle group above has a subgroup: the cyclic group with three elements. A cyclic group is a group where every element is a power of some other element.

For example, we could represent the cyclic group of order 3 as the roots of unity ($z^{3} = 1$) with the group being multiplication.

$\{ e^{2\pi i \frac{0}{3}}, e^{2\pi i \frac{1}{3}}, e^{2\pi i \frac{2}{3}}\}$

As points in the complex plane, the group elements correspond to points on an n-gon.

Symmetry groups have been classified both in the infinite and finite cases. For example, the finite simple groups come in the following varieties:

- cyclic groups with prime numbers of elements

- alternating groups with at least 5 elements

- groups that are reminisicent of continuous Lie groups

- the 26 sporadic groups, the largest of which is the so-called Monster Group

Galois's insight was to describe a polynomial in terms of the finite symmetry group of its roots.

The symmetry group of the roots is determined by listing out all closed algebraic relationships between the roots (like $AB = 1$, $A + \frac{1}{2}C = 0$, etc, where $A, B, C$ are roots), and where you are only allowed to use rational coefficients in the expressions.

Then: you look at all the ways you can swap the roots in those expressions that keeps them true.

In other words, perhaps it's also true that $A + \frac{1}{2}B = 0$ and $AC = 1$, in which case, we could swap $B \Leftrightarrow C$ and all our equations will still work.

So we list out all the possible swaps, all the possible permutations of the roots that leave all the algebraic expressions true, and these will form a group, the Galois group of the polynomial.

Galois's theorem is that: when the Galois group of a polynomial can be decomposed into cyclic groups, then that polynomial is solvable. In other words, there's the equivalent of a "quadratic formula," an expression involving only integers and addition/subtraction/multiplication/division/exponentiation/root-taking, where you plug in the coefficients, do a finite amount of algebra, and out pop the roots.

Otherwise you have to approximate the roots of the polynomial! Implying that the transformation from coefficients to roots involves an infinite amount of algebra. This is generally the case for polynomials of degree 5 or higher, as once you have polynomials of degree 5, you can have, for example, an alternating group as a subgroup.

So what can we do with polynomials? Well, we can evaluate them, integrate them, differentiate them, solve them.

Evaluation is just a generalization of arithmetic: think of a polynomial like bundle of some arbitrary amount of algebra under the heading of a single symbol. In the simplest case, for example, consider these interpretations of "2":

$ f(z) = 2 + z$

$ f(z) = 2z$

$ f(z) = z^2$

But you might ask: if polynomials are the new "numbers", can we do arithmetic with polynomials themselves?

Naturally, we can add and subtract polynomials $a(z) + b(z) = c(z)$. We can multiply polynomials, which just corresponds to combining their roots (like pebbles in a pile), but when we come to divide polynomials, there's an interesting development.

If we have some $\frac{p(z)}{q(z)}$, it's possible some of their roots will cancel, but beyond that, where $q(z)$ has roots, $\frac{p(z)}{q(z)}$ has poles: it goes to $\infty$ there. We decide this is fine, and we get the idea of a "rational function," like a rational number, but it's a ratio between two polynomials, and it's completely specified by its roots and its poles.

One consequence of this is that we can view rational functions as functions from the sphere to the sphere.

If we plug in a complex number $z$ into $f(z) = \frac{p(z)}{q(z)}$, we get out either a complex number, or else infinity. So we decide to interpret this in terms of the Riemann sphere. The complex number $z$ via the stereographic projection gets mapped to an (x, y, z) point on the sphere, and the rational function maps this point to another point on the sphere. Recall that $\infty$ just corresponds to the pole of projection, say the South Pole.

If we want to evaluate $f(\infty)$, we take $f(\infty) = \lim_{z\rightarrow \infty} f(z)$.

The simplest rational functions are known the Mobius transformations: $f(z) = \frac{az + b}{cz + d}$, where $ad - bc \neq 0$. There's a root upstairs and a pole downstars: $f(-\frac{b}{a}) = 0$, and $f(-\frac{d}{c}) = \infty$.

Moreover, $f(\infty) = \lim_{z\rightarrow \infty} \frac{az + b}{cz + d} = \frac{a}{c}.$

The idea is that when $z \rightarrow \infty$, $b$ and $d$ become irrelevant; but then we have $\frac{az}{cz} = \frac{a}{c}$. If $c = 0$, we find that $f(\infty) = \infty$.

A Mobius transformation turns out to be a 1-to-1 transformation: it maps each point on the sphere to unique point on the sphere. These transformations happen to be conformal, in other words, they preserve angles, but not distances, and take circles to circles. If you can figure out where 3 unique points are mapped to, you can figure out where all the points are mapped to.

Geometrically, you can imagine that we take a set of points on the plane and map them to the sphere via the stereographic projection; we're then allowed to rotate the sphere and translate it in 3D; we then project the points back to the plane. In this way, all Mobius transformations can be obtained.

In fact, the Mobius transformations consists of combinations of rotations and boosts of the sphere (and also flipping the projection axis, etc). There are in essence 6 basic rotations and boosts (rotations around X, Y, Z; boosts along X, Y, Z), and this relates to the six degrees of freedom in the geometrical picture (the ability to rotate in X, Y, Z; and the ability to translate in X, Y, Z).

For example, we can rotate the sphere 180 degrees around the X axis with:

$f(z) = \frac{1}{z}$

Let's check. Obviously, this should fix the points $1$ and $-1$ since these correspond to $X+$ and $X-$.

$f(1) = 1$

$f(-1) = -1$

When we rotate a half turn around the X axis, we should take $Y+$ to $Y-$:

$f(i) = -i$

$f(-i) = i$

And finally, we should also flip $Z+$ and $Z-$.

$f(0) = \infty$

$f(\infty) = 0$

The Mobius transformations actually form a group: a continous symmetry group.

Watch:

$f(z) = \frac{az + b}{cz + d}$

$g(z) = \frac{\alpha z + \beta}{\gamma z + \delta}$

$ f(g(z)) = \frac{a(\frac{\alpha z + \beta}{\gamma z + \delta}) + b}{c(\frac{\alpha z + \beta}{\gamma z + \delta}) + d}$.

But this itself has the form of a Mobius transformation!

$f(g(z)) = \frac{ a \alpha z + a \beta + b \gamma z + \delta b}{c \alpha z + c \beta + d \gamma z + \delta d} = \frac{ (a \alpha + b \gamma) z + (a \beta + \delta b)}{ (c \alpha + d \gamma) z + (c \beta + \delta d)}$.

And indeed, we know: we can rotate a sphere around one axis, and then rotate the sphere around another axis, and there's a third rotation that takes us there directly.

If we consider higher order rational functions, they won't be 1-to-1. This is obvious since all the poles get mapped to the same point: $\infty$.

But: recall that a rational function is defined by its poles and roots. We could imagine Mobius transforming these roots and poles, which takes them each to another set of roots and poles uniquely. Since a Mobius transformation maps each point on the sphere to a unique point on the sphere, it follows that a Mobius transformation also maps each unique rational function to a unique rational function. So the Mobius transformations are the "automorphism group" of the rational functions, the group of transformations from the rational functions to themselves.

They also happen to represent the symmetry group of the "celestial sphere," the sphere of incoming momenta in special relativity. We see points of light coming in from certain directions: we could also see them from a rotated vantage point (if we're spinning) or a boosted vantage point (if we're moving at a constant velocity in some direction--the points get boosted in the direction of motion).

In other words, a "constellation," "a rational function," "a polynomial number," is only defined up to a Mobius transformation, which aligns the X, Y, and Z axes.

So our new kind of number is a "rational function," a ratio of polynomials. We can apply algebra to them just like numbers, even as they represent "bundles of algebra" themselves. They can be defined by a set of poles and roots, which are like the primes, the atoms of a rational function.

And so at this stage, we can think of a "composite" as a "constellation" on the sphere, a set of (x, y, z) points, corresponding via stereographic projection to a set of complex roots (where $\infty$ is allowed to be a root).

Moreover, there's some new operations at this stage: integration, differentiation, "solving." And a new, separate understanding of "atoms" in terms of symmetry groups and their simple subgroups, finite and infinite, which we shall see has great consequence.