# CPE 1040

This is Learning Progression 004 of the course CPE 1040: Introduction to Computer Engineering at MSU Denver.

Table of Contents

=================

* [CPE 1040](#cpe-1040)

* [Learning Progression 004: External LEDs](#learning-progression-004-external-leds)

* [Lab kit](#lab-kit)

* [Parts for progression](#parts-for-progression)

* [Steps](#steps)

* [Step 1: Binary](#step-1-binary)

* [1\. Study](#1-study)

* [Positional numeral systems](#positional-numeral-systems)

* [Unsigned integers](#unsigned-integers)

* [Finite bit width](#finite-bit-width)

* [Primitive data types revisited](#primitive-data-types-revisited)

* [Signed integers](#signed-integers)

* [IEEE 754 floating point](#ieee-754-floating-point)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply)

* [3\. Present](#3-present)

* [Step 2: Data & memory](#step-2-data--memory)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-1)

* [Arrays and memory](#arrays-and-memory)

* [Memory layout](#memory-layout)

* [Numeric types, buffers, and caches](#numeric-types-buffers-and-caches)

* [Addressing](#addressing)

* [References and pointers](#references-and-pointers)

* [Types of memory](#types-of-memory)

* [Memory management](#memory-management)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-1)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-1)

* [Step 3: Computation](#step-3-computation)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-2)

* [Addition](#addition)

* [Subtraction in 2s complement](#subtraction-in-2s-complement)

* [Shifting](#shifting)

* [Multiplication](#multiplication)

* [Floating point arithmetic](#floating-point-arithmetic)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-2)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-2)

* [Step 4: Minimal assembly (part 1)](#step-4-minimal-assembly-part-1)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-3)

* [Central processing unit](#central-processing-unit)

* [Instruction set architecture](#instruction-set-architecture)

* [Registers](#registers)

* [Processor and memory](#processor-and-memory)

* [Load and store](#load-and-store)

* [Branching revisited](#branching-revisited)

* [Status bits](#status-bits)

* [Clock cycles](#clock-cycles)

* [Minimal instruction set CPU](#minimal-instruction-set-cpu)

* [F\-4 MISC 16 bit instruction set](#f-4-misc-16-bit-instruction-set)

* [In plain words](#in-plain-words)

* [Symbols](#symbols)

* [micro:bit hex files](#microbit-hex-files)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-3)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-3)

* [Step 5: Minimal assembly (part 2)](#step-5-minimal-assembly-part-2)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-4)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-4)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-4)

* [Step 6: Electromagnetism](#step-6-electromagnetism)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-5)

* [Fundamental interaction](#fundamental-interaction)

* [Electrostatics & magenetostatics](#electrostatics--magenetostatics)

* [Theories of electromagnetism](#theories-of-electromagnetism)

* [Charge, voltage, and current](#charge-voltage-and-current)

* [Resistance](#resistance)

* [Ohm's law](#ohms-law)

* [Power](#power)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-5)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-5)

* [Step 7: Circuits & circuit elements](#step-7-circuits--circuit-elements)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-6)

* [Circuits](#circuits)

* [Short circuit](#short-circuit)

* [Circuit elements](#circuit-elements)

* [Resistors in series and in parallel](#resistors-in-series-and-in-parallel)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-6)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-6)

* [Step 8: Multimeter](#step-8-multimeter)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-7)

* [Measuring voltage](#measuring-voltage)

* [Different grounds](#different-grounds)

* [Measuring current](#measuring-current)

* [Measuring resistance](#measuring-resistance)

* [Checking for continuity](#checking-for-continuity)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-7)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-7)

* [Step 9: Basic LED circuit](#step-9-basic-led-circuit)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-8)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-8)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-8)

* [Step 10: micro:bit breakout board](#step-10-microbit-breakout-board)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-9)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-9)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-9)

* [Step 11: micro:bit GPIO pins](#step-11-microbit-gpio-pins)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-10)

* [micro:bit I/O](#microbit-io)

* [Digital vs analog](#digital-vs-analog)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-10)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-10)

* [Step 12: Screensaver extension](#step-12-screensaver-extension)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-11)

* [Extending a program](#extending-a-program)

* [Defining extra rows](#defining-extra-rows)

* [Choice of pins](#choice-of-pins)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-11)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-11)

* [Resources](#resources)

## Learning Progression 004: External LEDs

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

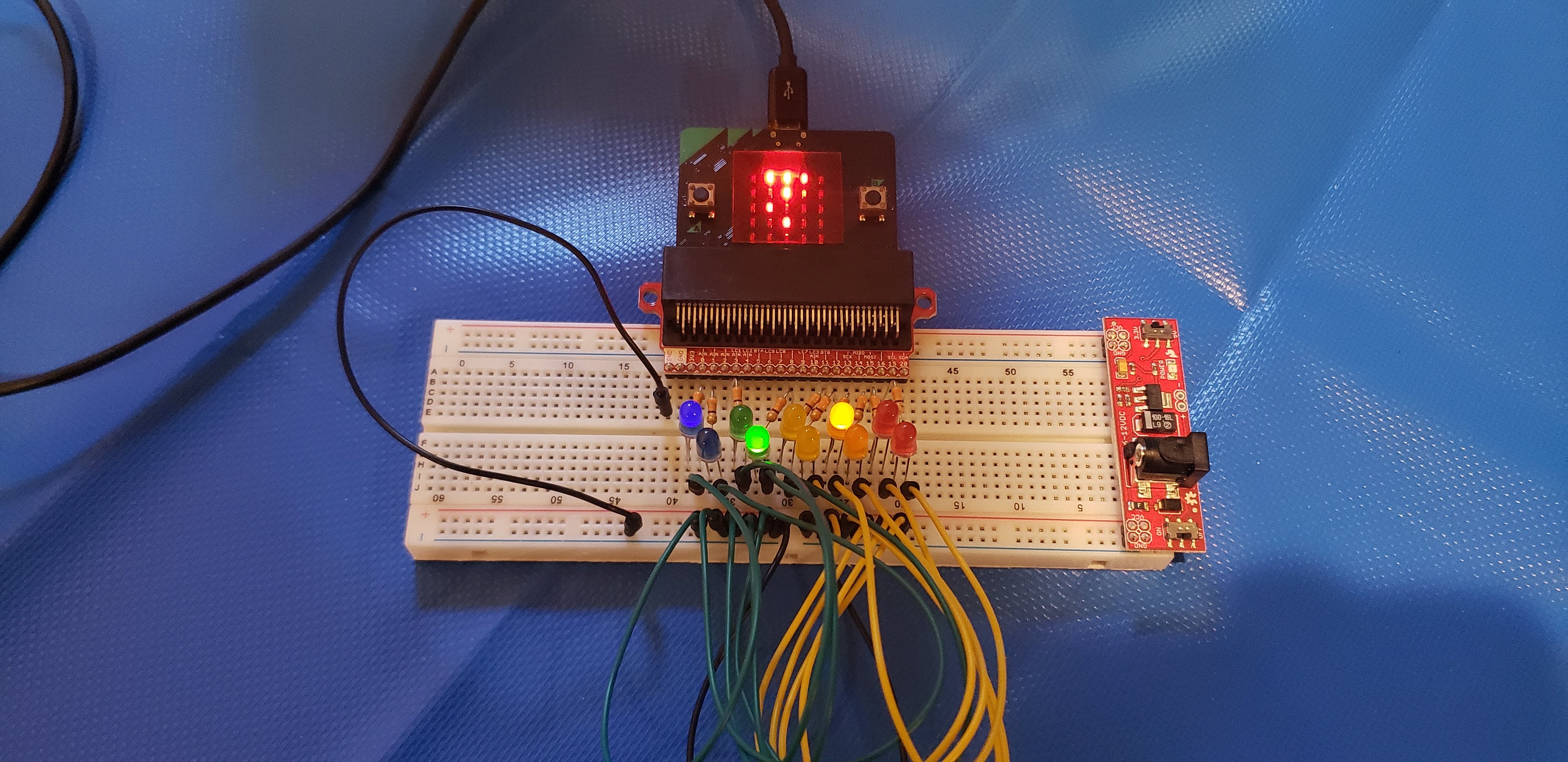

This progression introduces fundamentals of computing, including the binary system of data representation as well as the basics of memory and processing. We introduce assembly language in the context of a minimal instruction set processor. This is where the lowest layer of the software stack and the highest layer of the hardware stack coexist, and where user programs are translated into machine code and executed by the processor one instruction at a time. This is also the level of computing which directly correpsonds to the simplest theoretical models of a computer. We also introduce the input-output capabilities of the micro:bit and build an external circuit to serve as an extension to the built-in 5x5 LED matrix to run our Screensavers program on.

## Lab kit

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The lab kit is described in detail in a [separate page](lab-kit.md). Please, make sure you read the care and safety instructions embedded for most of the kit components.

### Parts for progression

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

1. Breadboard.

2. Breadboard power supply with wall plug.

3. micro:bit breakout board (connector).

4. 330 Ohm resistor (10 count).

5. LEDs (10 count).

6. Wires.

7. Multimeter with needle-tipped probes.

## Steps

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

### Step 1: Binary

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

#### 1. Study

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

##### Positional numeral systems

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The most widely used number system is _decimal_. What does "decimal" actually mean? Let us list the obvious:

1. [Decimal](https://www.etymonline.com/word/decimal) means 10.

2. The decimal system has 10 symbols, called _digits_: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9.

3. It's popularity tends to be attributed to the fact that humans have 10 digits on their hands and they learned to count on them in prehistoric times.

Some aspects that are less obvious (mostly because they have become deeply habitual) are:

1. The name "decimal" indicates the _base_ of the number system, which is 10. Note that the base is the _highest digit plus 1_, which has to do with the fact that 0 is the first digit.

2. Every number expresses a sum of _powers_ of the base 10. For example, the number 359 unequivocally means _three-hundred-and-fifty-nine_, or

Table of Contents

=================

* [CPE 1040](#cpe-1040)

* [Learning Progression 004: External LEDs](#learning-progression-004-external-leds)

* [Lab kit](#lab-kit)

* [Parts for progression](#parts-for-progression)

* [Steps](#steps)

* [Step 1: Binary](#step-1-binary)

* [1\. Study](#1-study)

* [Positional numeral systems](#positional-numeral-systems)

* [Unsigned integers](#unsigned-integers)

* [Finite bit width](#finite-bit-width)

* [Primitive data types revisited](#primitive-data-types-revisited)

* [Signed integers](#signed-integers)

* [IEEE 754 floating point](#ieee-754-floating-point)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply)

* [3\. Present](#3-present)

* [Step 2: Data & memory](#step-2-data--memory)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-1)

* [Arrays and memory](#arrays-and-memory)

* [Memory layout](#memory-layout)

* [Numeric types, buffers, and caches](#numeric-types-buffers-and-caches)

* [Addressing](#addressing)

* [References and pointers](#references-and-pointers)

* [Types of memory](#types-of-memory)

* [Memory management](#memory-management)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-1)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-1)

* [Step 3: Computation](#step-3-computation)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-2)

* [Addition](#addition)

* [Subtraction in 2s complement](#subtraction-in-2s-complement)

* [Shifting](#shifting)

* [Multiplication](#multiplication)

* [Floating point arithmetic](#floating-point-arithmetic)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-2)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-2)

* [Step 4: Minimal assembly (part 1)](#step-4-minimal-assembly-part-1)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-3)

* [Central processing unit](#central-processing-unit)

* [Instruction set architecture](#instruction-set-architecture)

* [Registers](#registers)

* [Processor and memory](#processor-and-memory)

* [Load and store](#load-and-store)

* [Branching revisited](#branching-revisited)

* [Status bits](#status-bits)

* [Clock cycles](#clock-cycles)

* [Minimal instruction set CPU](#minimal-instruction-set-cpu)

* [F\-4 MISC 16 bit instruction set](#f-4-misc-16-bit-instruction-set)

* [In plain words](#in-plain-words)

* [Symbols](#symbols)

* [micro:bit hex files](#microbit-hex-files)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-3)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-3)

* [Step 5: Minimal assembly (part 2)](#step-5-minimal-assembly-part-2)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-4)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-4)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-4)

* [Step 6: Electromagnetism](#step-6-electromagnetism)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-5)

* [Fundamental interaction](#fundamental-interaction)

* [Electrostatics & magenetostatics](#electrostatics--magenetostatics)

* [Theories of electromagnetism](#theories-of-electromagnetism)

* [Charge, voltage, and current](#charge-voltage-and-current)

* [Resistance](#resistance)

* [Ohm's law](#ohms-law)

* [Power](#power)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-5)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-5)

* [Step 7: Circuits & circuit elements](#step-7-circuits--circuit-elements)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-6)

* [Circuits](#circuits)

* [Short circuit](#short-circuit)

* [Circuit elements](#circuit-elements)

* [Resistors in series and in parallel](#resistors-in-series-and-in-parallel)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-6)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-6)

* [Step 8: Multimeter](#step-8-multimeter)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-7)

* [Measuring voltage](#measuring-voltage)

* [Different grounds](#different-grounds)

* [Measuring current](#measuring-current)

* [Measuring resistance](#measuring-resistance)

* [Checking for continuity](#checking-for-continuity)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-7)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-7)

* [Step 9: Basic LED circuit](#step-9-basic-led-circuit)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-8)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-8)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-8)

* [Step 10: micro:bit breakout board](#step-10-microbit-breakout-board)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-9)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-9)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-9)

* [Step 11: micro:bit GPIO pins](#step-11-microbit-gpio-pins)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-10)

* [micro:bit I/O](#microbit-io)

* [Digital vs analog](#digital-vs-analog)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-10)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-10)

* [Step 12: Screensaver extension](#step-12-screensaver-extension)

* [1\. Study](#1-study-11)

* [Extending a program](#extending-a-program)

* [Defining extra rows](#defining-extra-rows)

* [Choice of pins](#choice-of-pins)

* [2\. Apply](#2-apply-11)

* [3\. Present](#3-present-11)

* [Resources](#resources)

## Learning Progression 004: External LEDs

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

This progression introduces fundamentals of computing, including the binary system of data representation as well as the basics of memory and processing. We introduce assembly language in the context of a minimal instruction set processor. This is where the lowest layer of the software stack and the highest layer of the hardware stack coexist, and where user programs are translated into machine code and executed by the processor one instruction at a time. This is also the level of computing which directly correpsonds to the simplest theoretical models of a computer. We also introduce the input-output capabilities of the micro:bit and build an external circuit to serve as an extension to the built-in 5x5 LED matrix to run our Screensavers program on.

## Lab kit

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The lab kit is described in detail in a [separate page](lab-kit.md). Please, make sure you read the care and safety instructions embedded for most of the kit components.

### Parts for progression

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

1. Breadboard.

2. Breadboard power supply with wall plug.

3. micro:bit breakout board (connector).

4. 330 Ohm resistor (10 count).

5. LEDs (10 count).

6. Wires.

7. Multimeter with needle-tipped probes.

## Steps

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

### Step 1: Binary

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

#### 1. Study

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

##### Positional numeral systems

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The most widely used number system is _decimal_. What does "decimal" actually mean? Let us list the obvious:

1. [Decimal](https://www.etymonline.com/word/decimal) means 10.

2. The decimal system has 10 symbols, called _digits_: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 8, 9.

3. It's popularity tends to be attributed to the fact that humans have 10 digits on their hands and they learned to count on them in prehistoric times.

Some aspects that are less obvious (mostly because they have become deeply habitual) are:

1. The name "decimal" indicates the _base_ of the number system, which is 10. Note that the base is the _highest digit plus 1_, which has to do with the fact that 0 is the first digit.

2. Every number expresses a sum of _powers_ of the base 10. For example, the number 359 unequivocally means _three-hundred-and-fifty-nine_, or  . Any decimal number can be expressed like this. Note that any number raised to the power 0 is, by definition, equal to 1.

3. The powers of the base are equal to the indices of the digit positions, counting _from right to left starting at 0_. For example,

```

Digits 359

Indices 210

```

The position of a digit immediately tells us whether it represents _ones_. _tens_, _hundreds_, _thousands_, _ten-thousands_, etc.

What all of this means is that the decimal number (aka _numeral_) system is just one example of _positional_ number systems. In contrast, the [Roman numeral system](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_numerals) is _not_ positional. For example, consider the numbers

. Any decimal number can be expressed like this. Note that any number raised to the power 0 is, by definition, equal to 1.

3. The powers of the base are equal to the indices of the digit positions, counting _from right to left starting at 0_. For example,

```

Digits 359

Indices 210

```

The position of a digit immediately tells us whether it represents _ones_. _tens_, _hundreds_, _thousands_, _ten-thousands_, etc.

What all of this means is that the decimal number (aka _numeral_) system is just one example of _positional_ number systems. In contrast, the [Roman numeral system](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_numerals) is _not_ positional. For example, consider the numbers  (9 in decimal) and

(9 in decimal) and  (11 in decimal).

**Question 1.1.1:** Why are the Roman numerals not a positional number system?

The [_binary_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_number) number system (_binary_, for short) is another positional numeral system.

**Question 1.1.2:** What is the base of binary?

**Question 1.1.3:** What are the symbols of binary? How are they called?

**Question 1.1.4:** Express the binary number

(11 in decimal).

**Question 1.1.1:** Why are the Roman numerals not a positional number system?

The [_binary_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_number) number system (_binary_, for short) is another positional numeral system.

**Question 1.1.2:** What is the base of binary?

**Question 1.1.3:** What are the symbols of binary? How are they called?

**Question 1.1.4:** Express the binary number  as a sum of powers of the base.

**Question 1.1.5:** What does

as a sum of powers of the base.

**Question 1.1.5:** What does  represent in binary?

##### Unsigned integers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The simplest data type in computing is the _unsigned integer_. "Unsigned" means _non-negative_. "Integer" means _whole number_. Here are the first 16 unsigned integers, in both decimal and binary:

Decimal | Binary

-- | --

represent in binary?

##### Unsigned integers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The simplest data type in computing is the _unsigned integer_. "Unsigned" means _non-negative_. "Integer" means _whole number_. Here are the first 16 unsigned integers, in both decimal and binary:

Decimal | Binary

-- | --

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|  In programming, a binary number is written with the prefix `0b`. For example, `0b1` and `0b0001` both represent

In programming, a binary number is written with the prefix `0b`. For example, `0b1` and `0b0001` both represent  .

**Question 1.1.6:** What are the _bit patterns_ for

.

**Question 1.1.6:** What are the _bit patterns_ for  ,

,  , and

, and  ? Use the following function on the micro:bit simulator and/or device:

```javascript

// Example 1.1.1

/**

* Converts an unsigned decimal integer to a binary bit pattern string.

*

* Quotient Remainder Condition Result

* 3 : 2 = 1.5 ------> 1 Q > floor(Q) 11

* 1 : 2 = 0.5 ------> 1 floor(Q) == 0

*

* 2 : 2 = 1.0 ------> 0 Q == floor(Q) 10

* 1 : 2 = 0.5 ------> 1 floor(Q) == 0

*

* @param dec unsigned decimal integer

*/

function toUnsignedBinaryString(dec : number) : string {

let bin_array : number[] = []

let quotient : number = dec

let no_fraction : number

while (true) {

quotient /= 2

no_fraction = Math.floor(quotient)

if (quotient > no_fraction)

bin_array.insertAt(0, 1)

else

bin_array.insertAt(0, 0)

if (no_fraction == 0) break

quotient = no_fraction

}

return '0b' +

bin_array.map(

(value: number, index: number) =>

{ return value.toString(); }

).join('')

}

```

##### Finite bit width

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

A bit pattern of _any length_ can represent an unsigned integer. However, computers represent unsigned integers of _fixed bit width_, which is a power of 2. The most widely used bit widths are 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128. For example, here is the number

? Use the following function on the micro:bit simulator and/or device:

```javascript

// Example 1.1.1

/**

* Converts an unsigned decimal integer to a binary bit pattern string.

*

* Quotient Remainder Condition Result

* 3 : 2 = 1.5 ------> 1 Q > floor(Q) 11

* 1 : 2 = 0.5 ------> 1 floor(Q) == 0

*

* 2 : 2 = 1.0 ------> 0 Q == floor(Q) 10

* 1 : 2 = 0.5 ------> 1 floor(Q) == 0

*

* @param dec unsigned decimal integer

*/

function toUnsignedBinaryString(dec : number) : string {

let bin_array : number[] = []

let quotient : number = dec

let no_fraction : number

while (true) {

quotient /= 2

no_fraction = Math.floor(quotient)

if (quotient > no_fraction)

bin_array.insertAt(0, 1)

else

bin_array.insertAt(0, 0)

if (no_fraction == 0) break

quotient = no_fraction

}

return '0b' +

bin_array.map(

(value: number, index: number) =>

{ return value.toString(); }

).join('')

}

```

##### Finite bit width

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

A bit pattern of _any length_ can represent an unsigned integer. However, computers represent unsigned integers of _fixed bit width_, which is a power of 2. The most widely used bit widths are 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128. For example, here is the number  in 8 bits, 16 bits, and 32 bits:

Bit width | Bit pattern

-- | --

8 | `0b10101100`

16 | `0b0000000010101100`

32 | `0b00000000000000000000000010101100`

The micro:bit has 32-bit unsigned integers.

**Question 1.1.6:** What is the bit pattern of the largest unsigned integer that can be represented in the micro:bit?

Finite bit-width means a limit on the largest number that can be represented. If a number is larger than the largest number that can be represented in the available number of bits, it _overflows_.

**Question 1.1.8:** Will

in 8 bits, 16 bits, and 32 bits:

Bit width | Bit pattern

-- | --

8 | `0b10101100`

16 | `0b0000000010101100`

32 | `0b00000000000000000000000010101100`

The micro:bit has 32-bit unsigned integers.

**Question 1.1.6:** What is the bit pattern of the largest unsigned integer that can be represented in the micro:bit?

Finite bit-width means a limit on the largest number that can be represented. If a number is larger than the largest number that can be represented in the available number of bits, it _overflows_.

**Question 1.1.8:** Will  overflow in 8-bit binary?

##### Primitive data types revisited

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The unsigned integer is one of the _primitive_ data types, along with _signed integers_, _floating-point numbes_, and _booleans_. A data type is primitive if it is represented in a [_word_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Word_(computer_architecture)). More on this when we tackle memory addressing and processor arithmetic in later steps.

**Question 1.1.9:** What is the word size of the micro:bit? _Hint: There are three ways to tell: (i) Reread the last two sections carefully; (ii) In the Wikipedia page, look at the table and find ARMv6-M, the architecture of the micro:bit processor; and (iii) Skim-read the [hardware overview](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/) documentation page for the micro:bit._

##### Signed integers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

_Signed integers_ are integers that can be negative and non-negative.

**Question 1.1.10:** How many different numbers can we represent with 4-bit binary patterns?

There are several [ways](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signed_number_representations) we can represent negative numbers. Here are examples with 4-bit numbers:

1. _Sign and value._ For example, if `0b0011` represents

overflow in 8-bit binary?

##### Primitive data types revisited

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The unsigned integer is one of the _primitive_ data types, along with _signed integers_, _floating-point numbes_, and _booleans_. A data type is primitive if it is represented in a [_word_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Word_(computer_architecture)). More on this when we tackle memory addressing and processor arithmetic in later steps.

**Question 1.1.9:** What is the word size of the micro:bit? _Hint: There are three ways to tell: (i) Reread the last two sections carefully; (ii) In the Wikipedia page, look at the table and find ARMv6-M, the architecture of the micro:bit processor; and (iii) Skim-read the [hardware overview](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/) documentation page for the micro:bit._

##### Signed integers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

_Signed integers_ are integers that can be negative and non-negative.

**Question 1.1.10:** How many different numbers can we represent with 4-bit binary patterns?

There are several [ways](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signed_number_representations) we can represent negative numbers. Here are examples with 4-bit numbers:

1. _Sign and value._ For example, if `0b0011` represents  , then

, then  will be represented by `0b1011`. The leftmost bit is used as a sign, with 0 representing + and 1 representing -. The problem with this representation is that it complicates computer arithmetic in _hardware_.

2. _One's complement_. For example,

will be represented by `0b1011`. The leftmost bit is used as a sign, with 0 representing + and 1 representing -. The problem with this representation is that it complicates computer arithmetic in _hardware_.

2. _One's complement_. For example,  will be represented by `0b1100`. The bits are just flipped. The problem with this representation is that it ends up with two different zeros: `0b0000` represents

will be represented by `0b1100`. The bits are just flipped. The problem with this representation is that it ends up with two different zeros: `0b0000` represents  and `0b1111` represents

and `0b1111` represents  .

3. [_Two's complement_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two%27s_complement). This is the representation of choice for modern computers because it eliminates the problems of the previous two. For example,

.

3. [_Two's complement_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two%27s_complement). This is the representation of choice for modern computers because it eliminates the problems of the previous two. For example,  is represented by `0b1101`.

Here is a short table of 2-bit numbers in decimal and the three binary representations (note that with 2 bits we can represents only 4 different numbers):

Decimal | Sign and value | 1s complement | 2s complement

-- | -- | -- | --

is represented by `0b1101`.

Here is a short table of 2-bit numbers in decimal and the three binary representations (note that with 2 bits we can represents only 4 different numbers):

Decimal | Sign and value | 1s complement | 2s complement

-- | -- | -- | --

| `0b01` | `0b01` | `0b01`

| `0b01` | `0b01` | `0b01`

| `0b00` | `0b00` | `0b00`

| `0b00` | `0b00` | `0b00`

| `0b10` | `0b11` | n/a

| `0b10` | `0b11` | n/a

| `0b11` | `0b10` | `0b11`

| `0b11` | `0b10` | `0b11`

| n/a | n/a | `0b10`

The signed integer is also a primitive type.

**Question 1.1.11:** If we can represent 32 different signed integer numbers, what is the largest (by absolute value) negative number that we can represent?

##### IEEE 754 floating point

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

There are many different ways to represent _real_ numbers in binary, but the established standard is the [IEEE 754 format](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-precision_floating-point_format). The full coverage of this standard is beyond the scope of this learning progression, so we will point out the most important elements:

1. The standard is based on the [_scientific notation_](https://www.mathsisfun.com/numbers/scientific-notation.html) for real numbers. For example:

1. The decimal real number

| n/a | n/a | `0b10`

The signed integer is also a primitive type.

**Question 1.1.11:** If we can represent 32 different signed integer numbers, what is the largest (by absolute value) negative number that we can represent?

##### IEEE 754 floating point

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

There are many different ways to represent _real_ numbers in binary, but the established standard is the [IEEE 754 format](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-precision_floating-point_format). The full coverage of this standard is beyond the scope of this learning progression, so we will point out the most important elements:

1. The standard is based on the [_scientific notation_](https://www.mathsisfun.com/numbers/scientific-notation.html) for real numbers. For example:

1. The decimal real number  will be written in scientific notation as

will be written in scientific notation as  .

2. For binary, analogously, the number

.

2. For binary, analogously, the number  will be written in scientific notation as

will be written in scientific notation as  . _Note that, for clarity, we follow the convention for writing the base and power in decimal!_

3. Finally, the number

. _Note that, for clarity, we follow the convention for writing the base and power in decimal!_

3. Finally, the number  will be represented in scientic notation as

will be represented in scientic notation as  .

2. The type is called "_floating_ point" precisely because the exponent can take a large range of signed integers, as shown in the examples above, which allows the fractional point to "float". In contrast, reals can be represented in _fixed-point_ format, as well, thought his format has narrower application.

3. The _single-precision_ floating point is a primitive type represented in 32 bits. The _double-precision_ floating point is a primitive type represented in 64 bits.

4. In either precision, the bit pattern is split in 3 sections, representing (with bit widths shown for single-precision) as follows:

1. (1 bit) The sign, either 0 (+) or 1 (-). For the first binary example above, this bit woulb be 1.

2. (8 bits). The _exponent_ (that is, the power). The exponent is represented in an _offset_ form (aka _excess_, aka _bias_) where 127 is added to the actual exponent (aka _excess-127_). In the first binary example, the 8-bit exponent in our example above will be

.

2. The type is called "_floating_ point" precisely because the exponent can take a large range of signed integers, as shown in the examples above, which allows the fractional point to "float". In contrast, reals can be represented in _fixed-point_ format, as well, thought his format has narrower application.

3. The _single-precision_ floating point is a primitive type represented in 32 bits. The _double-precision_ floating point is a primitive type represented in 64 bits.

4. In either precision, the bit pattern is split in 3 sections, representing (with bit widths shown for single-precision) as follows:

1. (1 bit) The sign, either 0 (+) or 1 (-). For the first binary example above, this bit woulb be 1.

2. (8 bits). The _exponent_ (that is, the power). The exponent is represented in an _offset_ form (aka _excess_, aka _bias_) where 127 is added to the actual exponent (aka _excess-127_). In the first binary example, the 8-bit exponent in our example above will be  . This offset form converts the signed number representing the exponent (we saw that the exponent can be both negative and non-negative) into an unsigned number, which helps with _sorting_ floating-point numbers.

3. (23 bits) The _significand_ (aka _mantissa_), which consists of the bits _after_ the _binary point_ (aka fractional point). In the first binary example, the fractional bit pattern is going to be `01011000000000000000000`. Note that because in scientific notation a binary number always has a 1 bit to the left (aka in front) of the fractional point, it is omitted from the representation.

5. Floating-point numbers are _inexact_. Because the significand has only 23 bits, any further precision is lost and rounded. Real numbers are _uncountably infinite_, but we can only represent a finite number of them.

**Question 1.1.12:** Why would it be easier to sort binary floating-point numbers with the exponent represented as an _unsigned integer_ rather than a _signed integer_? _Hint: In an ascending order, 0 sorts above 1, but signed integers that start with 1 are all smaller than any signed integer that starts with 0._

#### 2. Apply

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

1. Explain in detail (line by line) what the function in Example 1.1.1 does and why.

2. Write a function that converts a _binary pattern string_, like `01011001`, to a decimal number (which will be 89 in this case). _Hint: Sum of powers of the base, with a judicious choice of [string methods](https://www.tutorialspoint.com/typescript/typescript_strings.htm), which can be found under the **Text** bar in the **Advanced** section of the MakeCode menu._

3. **[Optional challenge, max 10 extra step points]** Write a program with the following functions and types:

1. Function `asUnsigned` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as an unsigned integer and return the decimal equivalent.

2. Function `asOnesComp` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as a 1s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent.

3. Function `asTwosComp` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as a 2s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent.

4. Function `asUnsignedAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as an unsigned integer and return the decimal equivalent.

5. Function `asOnesCompAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as a 1s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent. _Note: You will need to assume that the bit width is the smallest power of 2 larger or equal to the number of bits in the argument. You will need to read up on [sign extension](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_extension)._

6. Function `asTwosCompAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as a 2s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent. _See the note above._

7. Enumerated type `NumberRep` for the three different representations: `Unsigned`, `OnesComp`, and `TwosComp`.

8. Enumerated type `BitWidth` for the two cases of bit width in the above functions: `8` and `Any`.

9. Function `interpretBinary (pattern : string, repr : NumberRep, width : BitWidth)` to collect all functions in one.

4. **[Optional challenge, max 3 extra step points]** Write a function `toScientific` that takes a real number and shows (that is, scrolls) it on the micro:bit screen in decimal scientific notation.

5. **[Optional super challenge, max 16 extra step points]** Derive the 2s-complement representation of signed binary integers. Recommended progression:

1. Realize that with any fixed number of bits, you can only represent so many different numbers.

2. Represent the unsigned integers for a bit width of your choice (4+ recommended, power of 2 recommended).

3. Now that you have all the patterns listed in a particular order, find one feature that splits the set in two, with all other features the same. _Hint: The two sets should easily convert from one to the other using a bitwise operation._

4. One of the sets would obviously remain to represent the same non-negative numbers as before the split. The other can now be used to represent the negative numbers.

5. How will you order the two sets so that they are symmetric through application of the bitwise opration from (3)?

6. At this point, you should have arrived at 1s-complement signed integers of the bit width you chose in (2). Point out the problem with it.

7. The foremost design principles for a number representation is that it is _arithmetically correct_ and _computationally cheap_. How would you fix the problem you pointed out in (6) in accordance to these principles. _Hint: Flipping a bit is cheap. Adding 1 to a number is cheap._

8. Show the sequence of _cheap_ operations that will _correctly_ compute 9510 - 3710, in 2s-complement binary. _Hint: The silent overflow is a feature, not an error!_

#### 3. Present

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

In the [programs](programs) directory:

1. Add your program from 1.2.2 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-2.js`.

2. Add your program from 1.2.3 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-3.js`.

3. Add your program from 1.2.4 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-4.js`.

In the [Lab Notebook](README.md):

1. Answer question 1.1.1.

2. Answer question 1.1.2.

3. Answer question 1.1.3.

4. Answer question 1.1.4.

5. Answer question 1.1.5.

6. Answer question 1.1.6.

7. Answer question 1.1.7.

8. Answer question 1.1.8.

9. Answer question 1.1.9.

10. Answer question 1.1.10.

11. Answer question 1.1.11.

12. Answer question 1.1.12.

13. Write you narrative for the program explanation from 1.2.1.

14. Link to the program from 1.2.2.

15. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.2.

16. Link to the program from 1.2.3.

17. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.3.

18. Link to the program from 1.2.4.

19. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.4.

20. Write you narrative for the derivation from 1.2.5.

### Step 2: Data & memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

#### 1. Study

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

##### Arrays and memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

Arrays are a ordered collections of data elements, which allow individual elements to be retrieved by their index in the sequence. The index range is [0, N-1], where N is the total number of array elements. Arrays are a close analog to computer memory. Memory is organized as a large array, and the indices of the elements are called _addresses_. Each _byte_ (8-bits) has an address, starting from 0b000 up to the highest address depending on the size of the memory.

What do we mean by "memory"? Memory is a physical device capable of keeping a dynamic record of the _state_ of a _process_ (meaning, an activated program). The state includes all the data the process is working with. For a computer to execute a program, the program itself and the program's data needs to be in the computer's memory.

Here's a very simple sketch of memory, showing all the bits (shown as boxes) in 4 consecutive bytes with addresses shown on the left:

```

-----------------

0b0000 |0|1|1|1|0|0|0|0|

-----------------

0b0001 |1|1|0|1|0|1|1|0|

-----------------

0b0010 |1|0|0|0|1|1|0|1|

-----------------

0b0011 |0|0|1|1|0|0|1|0|

-----------------

```

Notice the _fixed bit width_ of data in memory.

Memory has only two basic functions, _Read_ and _Write_.

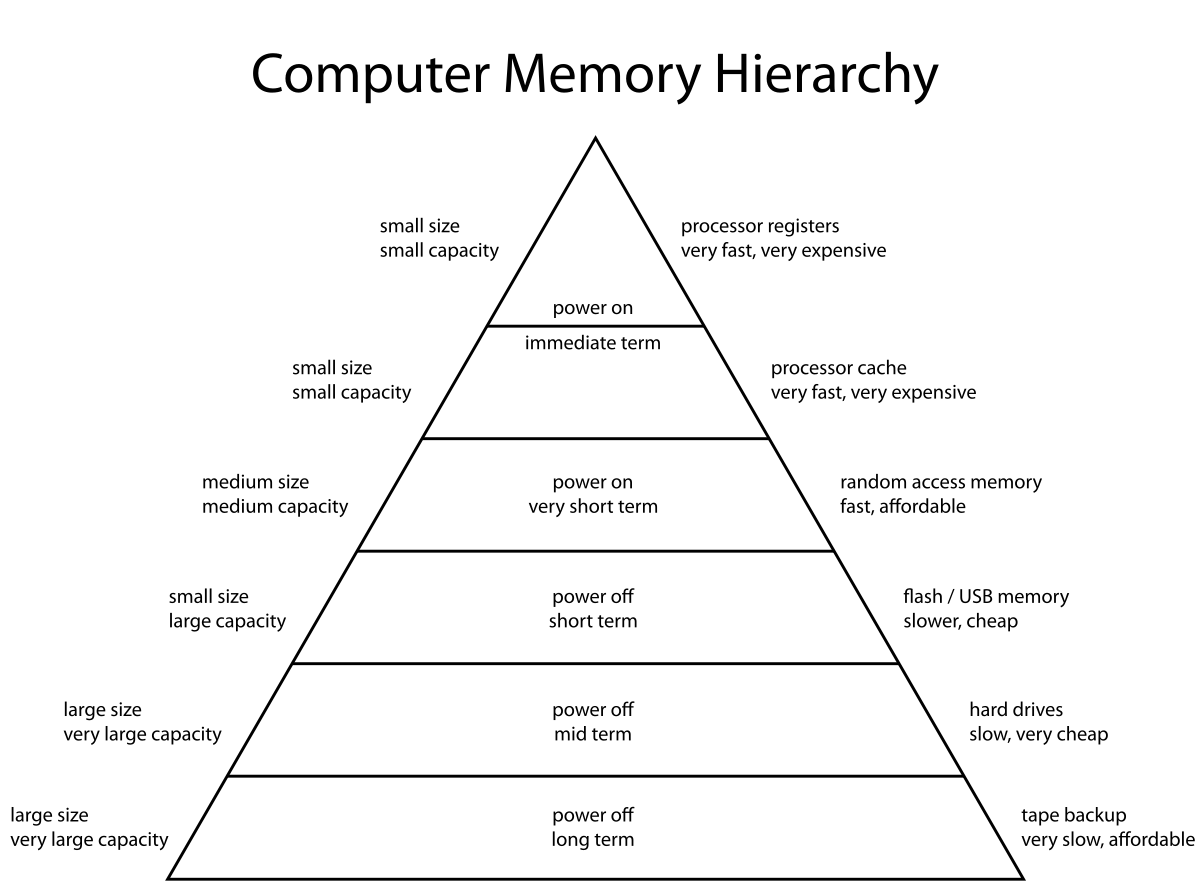

The most important property of memory is _speed_, in both reading and writing. The second most important property of memory is _capacity_. The more memory a computer has, the better. In the age of _big data_, memory is never enough, often by _orders of magnitude_.

##### Memory layout

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The simplicity of memory devices shift the burden of efficient usage to the software stack. Let's list some of the computational artifacts that we write to and read from memory:

1. We know that memory is _byte-addressed_. Any byte-sized data fits very efficiently into memory. Here are two examples:

1. [ASCII characters](http://www.asciitable.com/), which are a standard character set used by **all programming languages**, are 7-bits long. This character set is _fixed-length_, where length referes to the number of bytes one character takes. They all take one byte. In contrast, [_Unicode_](https://home.unicode.org/), which is the worldwide standard for representing all symbolic systems used by humanity, including [emoji](https://unicode.org/emoji/charts/full-emoji-list.html), due to its size, has adopted a _variable-length_ format.

2. _Machine learning (ML)_ has become an ubiquitous technology and is utilized in all computing environments, from large data centers to the smallest resource-constrained _Internet-of-Things (IoT)_ devices on the _edge_ of the Internet. ML is a _memory-heavy_ (meaining it uses a lot of memory) technology, but in the latter case, memory is severly constrained. The computational artifacts that ML produces are called _models_. These models contain the learned knowledge which machines use to solve the problems they were _trained_ for. The models are large and complex _data structures_. To be able to use such a model on IoT devices, it has to be _compressed_ to fit in their limited memory. One of the techniques is _byte-packing_, which reduces the numerical data of the model to a _byte array_.

2. Except for memory-constrained applications, data is usually represented in _words_. Today a word is usually 4 bytes, or 32 bits. All _primitive data types_ are represented in words, meaning:

1. They are read from and written to memory as words.

2. The processor works with word-sized _operands_ (e.g. for addition `a + b`, where `a` and `b` are the operands).

3. Because both memory and processor work with words, the computer is optimized to work with words, thus making the word-sized data the most efficient to manipulate.

3. The primitive types that we have encountered are:

1. Unsigned integers.

2. Signed integers.

3. Single-precision floating-point numbers.

4. Double-precision floating-point numbers (which use 2 words instead of one).

5. Booleans.

All of these look like bit-patterns in binary. For example, the bit pattern:

```

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0000 |1|0|0|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

```

represents 268225740810 in unsigned integers, -161270988810 in signed integers, or -9.48676900925e-20 in floating-point numbers. _Note that the last number is an example of a short-hand representation of scientific notation. The `e-20` means * 10-20._ So, data types are important to distinguish between different interpretation of binary patterns in memory.

4. Booleans are an interesting case. While a single bit can represent a boolean (0 for `false` and 1 for `true`), memories cannot manipulate (read or write) single bits. So, booleans are represented either by bytes, which are the smallest addressable units of memory, or words, which are the most efficient memory unit. Very often, data that are narrower than words are _word-aligned_ (meaning they are stored in words, with any extra bits set to zero). For example, here is how 4 word-aligned booleans will look in memory (the first two are `false` and the last two are `true`):

```

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0000 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0004 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0008 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|1|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b000c |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|1|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

```

Notice the addresses. They are 010, 410, 810, and 1210, because each boolean is 4 bytes wide.

5. The individual elements of arrays are stored _consecutively_ in memory. For example, the previous example may very well be the memory layout of the array `let boolArr : boolean = [false, false, true, true]` provided the micro:bit uses word alignment for booleans.

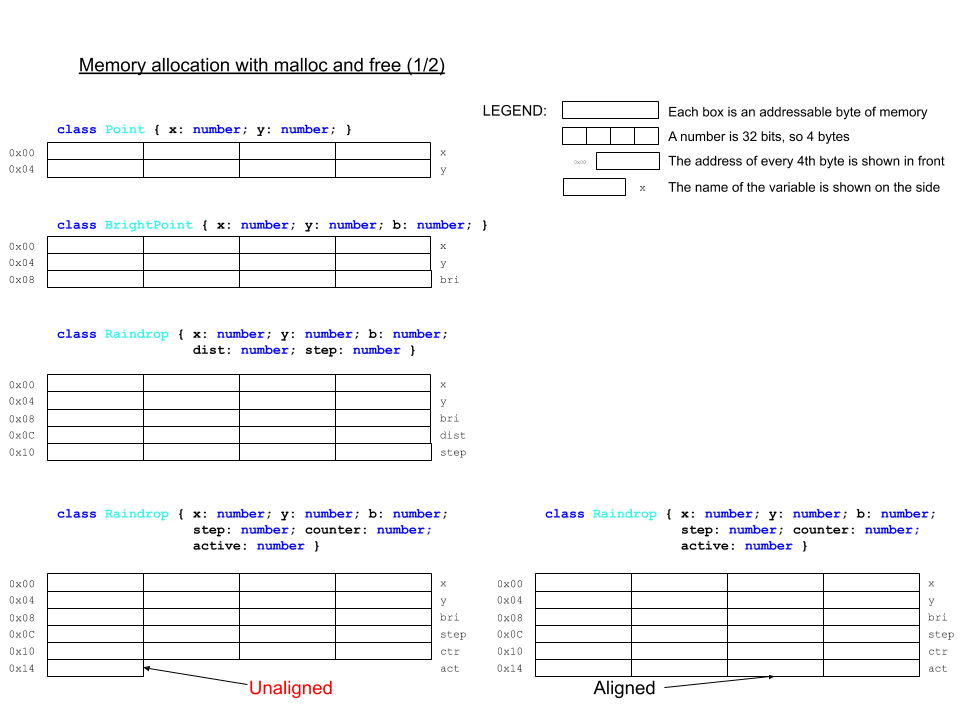

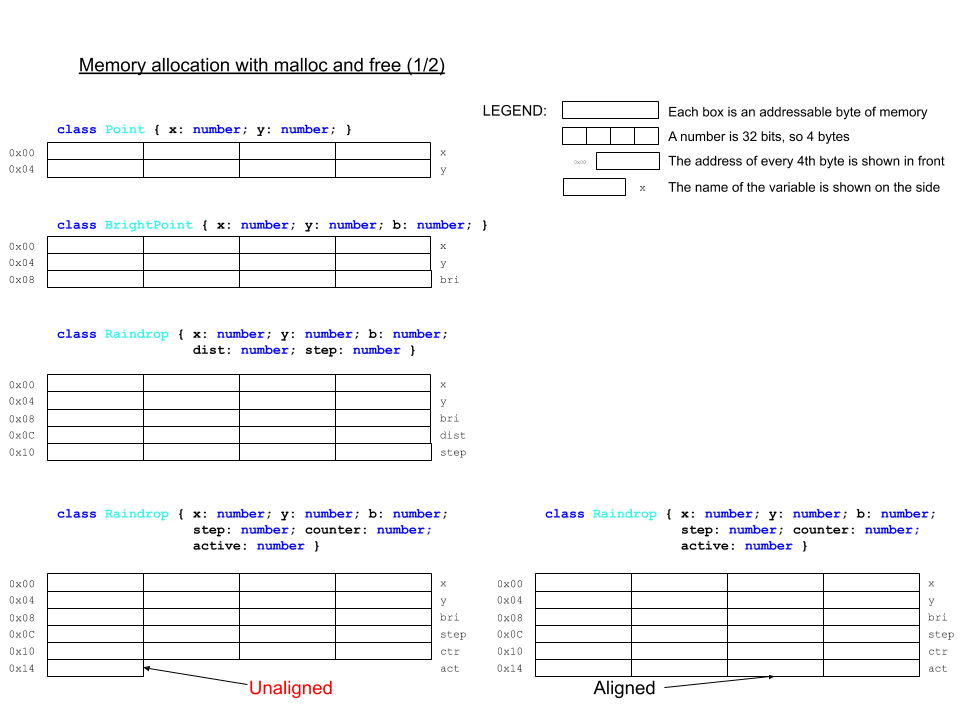

6. Object data is stored in memory blocks with the cumulative size of the class fields. The following sketch shows this for some familar classes from previous steps:

. This offset form converts the signed number representing the exponent (we saw that the exponent can be both negative and non-negative) into an unsigned number, which helps with _sorting_ floating-point numbers.

3. (23 bits) The _significand_ (aka _mantissa_), which consists of the bits _after_ the _binary point_ (aka fractional point). In the first binary example, the fractional bit pattern is going to be `01011000000000000000000`. Note that because in scientific notation a binary number always has a 1 bit to the left (aka in front) of the fractional point, it is omitted from the representation.

5. Floating-point numbers are _inexact_. Because the significand has only 23 bits, any further precision is lost and rounded. Real numbers are _uncountably infinite_, but we can only represent a finite number of them.

**Question 1.1.12:** Why would it be easier to sort binary floating-point numbers with the exponent represented as an _unsigned integer_ rather than a _signed integer_? _Hint: In an ascending order, 0 sorts above 1, but signed integers that start with 1 are all smaller than any signed integer that starts with 0._

#### 2. Apply

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

1. Explain in detail (line by line) what the function in Example 1.1.1 does and why.

2. Write a function that converts a _binary pattern string_, like `01011001`, to a decimal number (which will be 89 in this case). _Hint: Sum of powers of the base, with a judicious choice of [string methods](https://www.tutorialspoint.com/typescript/typescript_strings.htm), which can be found under the **Text** bar in the **Advanced** section of the MakeCode menu._

3. **[Optional challenge, max 10 extra step points]** Write a program with the following functions and types:

1. Function `asUnsigned` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as an unsigned integer and return the decimal equivalent.

2. Function `asOnesComp` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as a 1s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent.

3. Function `asTwosComp` to interpret an 8-bit binary pattern string as a 2s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent.

4. Function `asUnsignedAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as an unsigned integer and return the decimal equivalent.

5. Function `asOnesCompAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as a 1s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent. _Note: You will need to assume that the bit width is the smallest power of 2 larger or equal to the number of bits in the argument. You will need to read up on [sign extension](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_extension)._

6. Function `asTwosCompAny` to interpret a binary pattern string of arbitrary bit length as a 2s-complement signed integer and return the decimal equivalent. _See the note above._

7. Enumerated type `NumberRep` for the three different representations: `Unsigned`, `OnesComp`, and `TwosComp`.

8. Enumerated type `BitWidth` for the two cases of bit width in the above functions: `8` and `Any`.

9. Function `interpretBinary (pattern : string, repr : NumberRep, width : BitWidth)` to collect all functions in one.

4. **[Optional challenge, max 3 extra step points]** Write a function `toScientific` that takes a real number and shows (that is, scrolls) it on the micro:bit screen in decimal scientific notation.

5. **[Optional super challenge, max 16 extra step points]** Derive the 2s-complement representation of signed binary integers. Recommended progression:

1. Realize that with any fixed number of bits, you can only represent so many different numbers.

2. Represent the unsigned integers for a bit width of your choice (4+ recommended, power of 2 recommended).

3. Now that you have all the patterns listed in a particular order, find one feature that splits the set in two, with all other features the same. _Hint: The two sets should easily convert from one to the other using a bitwise operation._

4. One of the sets would obviously remain to represent the same non-negative numbers as before the split. The other can now be used to represent the negative numbers.

5. How will you order the two sets so that they are symmetric through application of the bitwise opration from (3)?

6. At this point, you should have arrived at 1s-complement signed integers of the bit width you chose in (2). Point out the problem with it.

7. The foremost design principles for a number representation is that it is _arithmetically correct_ and _computationally cheap_. How would you fix the problem you pointed out in (6) in accordance to these principles. _Hint: Flipping a bit is cheap. Adding 1 to a number is cheap._

8. Show the sequence of _cheap_ operations that will _correctly_ compute 9510 - 3710, in 2s-complement binary. _Hint: The silent overflow is a feature, not an error!_

#### 3. Present

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

In the [programs](programs) directory:

1. Add your program from 1.2.2 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-2.js`.

2. Add your program from 1.2.3 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-3.js`.

3. Add your program from 1.2.4 with filename `microbit-program-1-2-4.js`.

In the [Lab Notebook](README.md):

1. Answer question 1.1.1.

2. Answer question 1.1.2.

3. Answer question 1.1.3.

4. Answer question 1.1.4.

5. Answer question 1.1.5.

6. Answer question 1.1.6.

7. Answer question 1.1.7.

8. Answer question 1.1.8.

9. Answer question 1.1.9.

10. Answer question 1.1.10.

11. Answer question 1.1.11.

12. Answer question 1.1.12.

13. Write you narrative for the program explanation from 1.2.1.

14. Link to the program from 1.2.2.

15. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.2.

16. Link to the program from 1.2.3.

17. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.3.

18. Link to the program from 1.2.4.

19. Link to a demo video showing the execution of the program from 1.2.4.

20. Write you narrative for the derivation from 1.2.5.

### Step 2: Data & memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

#### 1. Study

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

##### Arrays and memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

Arrays are a ordered collections of data elements, which allow individual elements to be retrieved by their index in the sequence. The index range is [0, N-1], where N is the total number of array elements. Arrays are a close analog to computer memory. Memory is organized as a large array, and the indices of the elements are called _addresses_. Each _byte_ (8-bits) has an address, starting from 0b000 up to the highest address depending on the size of the memory.

What do we mean by "memory"? Memory is a physical device capable of keeping a dynamic record of the _state_ of a _process_ (meaning, an activated program). The state includes all the data the process is working with. For a computer to execute a program, the program itself and the program's data needs to be in the computer's memory.

Here's a very simple sketch of memory, showing all the bits (shown as boxes) in 4 consecutive bytes with addresses shown on the left:

```

-----------------

0b0000 |0|1|1|1|0|0|0|0|

-----------------

0b0001 |1|1|0|1|0|1|1|0|

-----------------

0b0010 |1|0|0|0|1|1|0|1|

-----------------

0b0011 |0|0|1|1|0|0|1|0|

-----------------

```

Notice the _fixed bit width_ of data in memory.

Memory has only two basic functions, _Read_ and _Write_.

The most important property of memory is _speed_, in both reading and writing. The second most important property of memory is _capacity_. The more memory a computer has, the better. In the age of _big data_, memory is never enough, often by _orders of magnitude_.

##### Memory layout

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The simplicity of memory devices shift the burden of efficient usage to the software stack. Let's list some of the computational artifacts that we write to and read from memory:

1. We know that memory is _byte-addressed_. Any byte-sized data fits very efficiently into memory. Here are two examples:

1. [ASCII characters](http://www.asciitable.com/), which are a standard character set used by **all programming languages**, are 7-bits long. This character set is _fixed-length_, where length referes to the number of bytes one character takes. They all take one byte. In contrast, [_Unicode_](https://home.unicode.org/), which is the worldwide standard for representing all symbolic systems used by humanity, including [emoji](https://unicode.org/emoji/charts/full-emoji-list.html), due to its size, has adopted a _variable-length_ format.

2. _Machine learning (ML)_ has become an ubiquitous technology and is utilized in all computing environments, from large data centers to the smallest resource-constrained _Internet-of-Things (IoT)_ devices on the _edge_ of the Internet. ML is a _memory-heavy_ (meaining it uses a lot of memory) technology, but in the latter case, memory is severly constrained. The computational artifacts that ML produces are called _models_. These models contain the learned knowledge which machines use to solve the problems they were _trained_ for. The models are large and complex _data structures_. To be able to use such a model on IoT devices, it has to be _compressed_ to fit in their limited memory. One of the techniques is _byte-packing_, which reduces the numerical data of the model to a _byte array_.

2. Except for memory-constrained applications, data is usually represented in _words_. Today a word is usually 4 bytes, or 32 bits. All _primitive data types_ are represented in words, meaning:

1. They are read from and written to memory as words.

2. The processor works with word-sized _operands_ (e.g. for addition `a + b`, where `a` and `b` are the operands).

3. Because both memory and processor work with words, the computer is optimized to work with words, thus making the word-sized data the most efficient to manipulate.

3. The primitive types that we have encountered are:

1. Unsigned integers.

2. Signed integers.

3. Single-precision floating-point numbers.

4. Double-precision floating-point numbers (which use 2 words instead of one).

5. Booleans.

All of these look like bit-patterns in binary. For example, the bit pattern:

```

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0000 |1|0|0|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|1|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

```

represents 268225740810 in unsigned integers, -161270988810 in signed integers, or -9.48676900925e-20 in floating-point numbers. _Note that the last number is an example of a short-hand representation of scientific notation. The `e-20` means * 10-20._ So, data types are important to distinguish between different interpretation of binary patterns in memory.

4. Booleans are an interesting case. While a single bit can represent a boolean (0 for `false` and 1 for `true`), memories cannot manipulate (read or write) single bits. So, booleans are represented either by bytes, which are the smallest addressable units of memory, or words, which are the most efficient memory unit. Very often, data that are narrower than words are _word-aligned_ (meaning they are stored in words, with any extra bits set to zero). For example, here is how 4 word-aligned booleans will look in memory (the first two are `false` and the last two are `true`):

```

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0000 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0004 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b0008 |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|1|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

0b000c |0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|0|1|

-----------------------------------------------------------------

```

Notice the addresses. They are 010, 410, 810, and 1210, because each boolean is 4 bytes wide.

5. The individual elements of arrays are stored _consecutively_ in memory. For example, the previous example may very well be the memory layout of the array `let boolArr : boolean = [false, false, true, true]` provided the micro:bit uses word alignment for booleans.

6. Object data is stored in memory blocks with the cumulative size of the class fields. The following sketch shows this for some familar classes from previous steps:

7. Of course, program code is also stored in memory. Here we need to distinguish among the following:

1. Program source code is stored as regular files in the file system, usually on drives, known as _secondary storage_. For example, `screensavers.js` is a source file.

2. Program _compiled_ binaries are stored as regular (though non-human readable) files, usually in _secondary storage_. For example, `microbit-screensavers.hex` is a compiled binary.

3. When a program is activated for execution, and becomes a _process_, the following happens:

1. A process metadata block is created for the program. This contains addresses, identification numbers, and miscellaneous process management data.

2. The program's compiled binaries are brought to _main memory_ (aka _primary storage_, the memory we have been talking about so far) in a _code segment_.

3. The program's data is also brought to main memory, in a data segment.

4. Additional memory for the program's execution is allocated and assigned to it.

5. Using the process metadata block, the process is put on a _queue_ (which is just a list where elements are added from one end and removed from the other) of processes ready to execute.

8. Just as variables are named data, functions and class methods are named code. When a function or method is called, the process knows where the code is. For class methods, they are not stored for each object, but only once for the class. When a method is called on an object, the class code is executed.

##### Numeric types, buffers, and caches

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The MakeCode environment silently lumps both integer and floating-point numbers in its `number` type. _Note that the type [`Number`](https://makecode.microbit.org/types/number) (note the capitalized type name) is a 32-bit 2s-complement signed integer, and its support is not very stable at present. Most importantly, the two types `number` and `Number` are not compatible and/or mutually interconvertible, at least in MakeCode, where the [JavaScript-like language we are using to program the micro:bit](https://makecode.com/language) is only a **subset** of TypeScript. For example:_

```javascript

// Example 2.1.1

let f : number = 3.4

basic.showNumber(f) // this works fine as showNumber takes a `number`-typed argument

let f : Number = 3

basic.showNumber(f) // this errors out with message "Argument of type 'Number' is not assignable to parameter of type 'number'."

```

So, we can use `Number` variables in our programs, but we cannot use them as arguments to functions which have `number` parameters.

TypeScript (in contrast to JavaScript) supports unsigned and signed integer types with explicit fixed bit-widths:

```javascript

// Example 2.1.2

// Unsigned integer types

let a : uint8 // range 0 to 255

let b : uint16 // range 0 to 65536

let c : uint32 // range 0 to 4294967295

// Signed integer types

let x : int8 // range -128 to 127

let y : int16 // range -32768 to 32767

let z : int32 // range -2147483648 to 2147483647

```

Note the following:

1. The ranges differ in correspondence to the bit width of the type: the larger the width, the larger the range.

2. The signed integers are 2s-complement, as can be seen from the fact that the negative integers are one more than the positive ones.

Arrays are not currently supported for these types. Instead of arrays, we can use _buffers_, which in general are unstructured blocks of memory where the programmer has full control over the memory layout. MakeCode supports the type [`Buffer`](https://makecode.microbit.org/types/buffer) for just such purpose. Here is an example:

```javascript

// Example 2.1.3

const BUFF_BYTE_SIZE = 16

let buff : Buffer = pins.createBuffer(BUFF_BYTE_SIZE)

for (let i=0; i

Things to notice:

1. The control line determines if the access is for reading (R) or writing (W). This is usually a single line (that is, 1 bit).

2. The data lines carry the value to be written or the value read, depending on the control line. It is as wide as there are bits (either 1 or 8 on the sketch).

3. When accessing a single bit or a single byte, we do not need address lines.

4. The address lines carry the value of the address. They are as many as necessary. On the bottom of the sketch, we have 8 bytes, each of which can be read or written independently. For this to happen, it needs to be _exclusively_ selected (that is, it and only it is selected, with the others deselected). For 4 different selector lines (one for each of the bytes), we can have a 2-bit address. Why? Because 4 different numbers can be represented with 2 bits (`0b00`, `0b01`, `0b10`, and `0b11`). The _2-to-4 decoder_ is a circuit which performs the following translation:

Address (2 bits) | Selector (4 bits)

--- | ---

00 | 0001

01 | 0010

10 | 0100

11 | 1000

A line is selected when it carries a value of 1 and deselected when it carries a value of 0.

**Question 2.1.1:** How many different selector lines can we control (that is, decode) with a 4-bit address?

##### References and pointers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

Now that we know about memory addresses, we can recall the short mention of references from a previous step. References are the programmatic equivalents of addresses, a sort of "invisible addresses". When arguments are passed to a function, they are either copied (pass _by value_) or referenced (pass _by reference_). To the programmer, this difference is invisible in most languages, JavaScript included. The difference is implemented based on the type of the argument: pass by value for primitive types, pass by reference for arrays and objects. While the programmer does not see the addresses themselves, reference-type _identifiers_ (meaning variable and function names) are matched to memory addresses when a program is activated and executed.

Some languages, most notably C and C++, have explicit reference types, called _pointers_. Here is a small example:

```c

// Example 2.1.4

int i = 6; // just a 32-bit signed integer variable, with a type `int`

int *ptr = &i; // a pointer variable, also 4 bytes, holding the address of i

// the type of ptr is `int *`, a pointer to an integer

printf("Integer %d, pointer dereference %d\n", i, *ptr); // a pointer can be dereferenced to show the value at the address it holds

```

Thus, languages like C and C++ give very low-level control over program memory than most other languages, including Java and JavaScript, where memory operations are invisible to the programmer and out if their direct control.

##### Types of memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

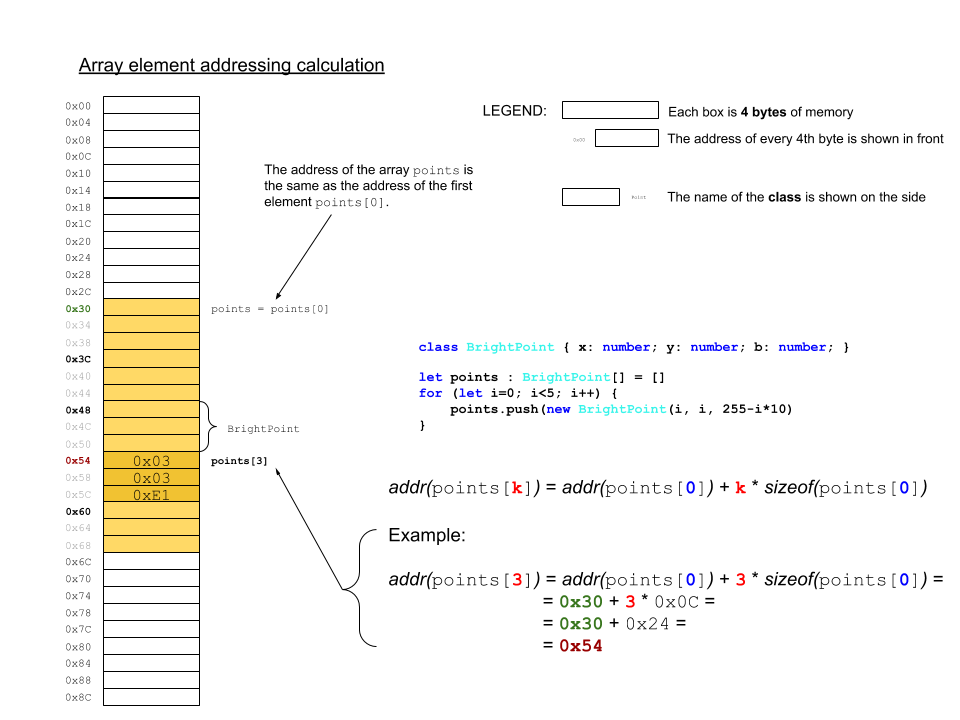

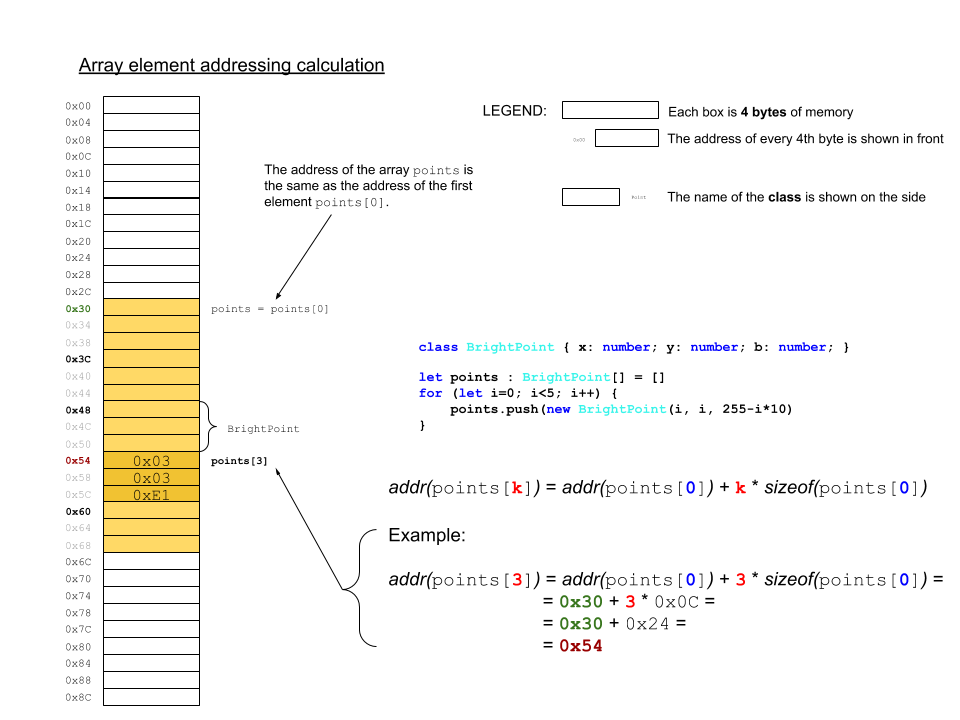

The elements of an array are stored in memory _continguously_ (meaning one after the other without gaps). This supports a very simple and efficient mechanism for element selection by index. The address of a particular element is calculated with the formula _base address + index * base type size_. Here is a sketch for illustration:

7. Of course, program code is also stored in memory. Here we need to distinguish among the following:

1. Program source code is stored as regular files in the file system, usually on drives, known as _secondary storage_. For example, `screensavers.js` is a source file.

2. Program _compiled_ binaries are stored as regular (though non-human readable) files, usually in _secondary storage_. For example, `microbit-screensavers.hex` is a compiled binary.

3. When a program is activated for execution, and becomes a _process_, the following happens:

1. A process metadata block is created for the program. This contains addresses, identification numbers, and miscellaneous process management data.

2. The program's compiled binaries are brought to _main memory_ (aka _primary storage_, the memory we have been talking about so far) in a _code segment_.

3. The program's data is also brought to main memory, in a data segment.

4. Additional memory for the program's execution is allocated and assigned to it.

5. Using the process metadata block, the process is put on a _queue_ (which is just a list where elements are added from one end and removed from the other) of processes ready to execute.

8. Just as variables are named data, functions and class methods are named code. When a function or method is called, the process knows where the code is. For class methods, they are not stored for each object, but only once for the class. When a method is called on an object, the class code is executed.

##### Numeric types, buffers, and caches

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The MakeCode environment silently lumps both integer and floating-point numbers in its `number` type. _Note that the type [`Number`](https://makecode.microbit.org/types/number) (note the capitalized type name) is a 32-bit 2s-complement signed integer, and its support is not very stable at present. Most importantly, the two types `number` and `Number` are not compatible and/or mutually interconvertible, at least in MakeCode, where the [JavaScript-like language we are using to program the micro:bit](https://makecode.com/language) is only a **subset** of TypeScript. For example:_

```javascript

// Example 2.1.1

let f : number = 3.4

basic.showNumber(f) // this works fine as showNumber takes a `number`-typed argument

let f : Number = 3

basic.showNumber(f) // this errors out with message "Argument of type 'Number' is not assignable to parameter of type 'number'."

```

So, we can use `Number` variables in our programs, but we cannot use them as arguments to functions which have `number` parameters.

TypeScript (in contrast to JavaScript) supports unsigned and signed integer types with explicit fixed bit-widths:

```javascript

// Example 2.1.2

// Unsigned integer types

let a : uint8 // range 0 to 255

let b : uint16 // range 0 to 65536

let c : uint32 // range 0 to 4294967295

// Signed integer types

let x : int8 // range -128 to 127

let y : int16 // range -32768 to 32767

let z : int32 // range -2147483648 to 2147483647

```

Note the following:

1. The ranges differ in correspondence to the bit width of the type: the larger the width, the larger the range.

2. The signed integers are 2s-complement, as can be seen from the fact that the negative integers are one more than the positive ones.

Arrays are not currently supported for these types. Instead of arrays, we can use _buffers_, which in general are unstructured blocks of memory where the programmer has full control over the memory layout. MakeCode supports the type [`Buffer`](https://makecode.microbit.org/types/buffer) for just such purpose. Here is an example:

```javascript

// Example 2.1.3

const BUFF_BYTE_SIZE = 16

let buff : Buffer = pins.createBuffer(BUFF_BYTE_SIZE)

for (let i=0; i

Things to notice:

1. The control line determines if the access is for reading (R) or writing (W). This is usually a single line (that is, 1 bit).

2. The data lines carry the value to be written or the value read, depending on the control line. It is as wide as there are bits (either 1 or 8 on the sketch).

3. When accessing a single bit or a single byte, we do not need address lines.

4. The address lines carry the value of the address. They are as many as necessary. On the bottom of the sketch, we have 8 bytes, each of which can be read or written independently. For this to happen, it needs to be _exclusively_ selected (that is, it and only it is selected, with the others deselected). For 4 different selector lines (one for each of the bytes), we can have a 2-bit address. Why? Because 4 different numbers can be represented with 2 bits (`0b00`, `0b01`, `0b10`, and `0b11`). The _2-to-4 decoder_ is a circuit which performs the following translation:

Address (2 bits) | Selector (4 bits)

--- | ---

00 | 0001

01 | 0010

10 | 0100

11 | 1000

A line is selected when it carries a value of 1 and deselected when it carries a value of 0.

**Question 2.1.1:** How many different selector lines can we control (that is, decode) with a 4-bit address?

##### References and pointers

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

Now that we know about memory addresses, we can recall the short mention of references from a previous step. References are the programmatic equivalents of addresses, a sort of "invisible addresses". When arguments are passed to a function, they are either copied (pass _by value_) or referenced (pass _by reference_). To the programmer, this difference is invisible in most languages, JavaScript included. The difference is implemented based on the type of the argument: pass by value for primitive types, pass by reference for arrays and objects. While the programmer does not see the addresses themselves, reference-type _identifiers_ (meaning variable and function names) are matched to memory addresses when a program is activated and executed.

Some languages, most notably C and C++, have explicit reference types, called _pointers_. Here is a small example:

```c

// Example 2.1.4

int i = 6; // just a 32-bit signed integer variable, with a type `int`

int *ptr = &i; // a pointer variable, also 4 bytes, holding the address of i

// the type of ptr is `int *`, a pointer to an integer

printf("Integer %d, pointer dereference %d\n", i, *ptr); // a pointer can be dereferenced to show the value at the address it holds

```

Thus, languages like C and C++ give very low-level control over program memory than most other languages, including Java and JavaScript, where memory operations are invisible to the programmer and out if their direct control.

##### Types of memory

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

The elements of an array are stored in memory _continguously_ (meaning one after the other without gaps). This supports a very simple and efficient mechanism for element selection by index. The address of a particular element is calculated with the formula _base address + index * base type size_. Here is a sketch for illustration:

There is a most important consequence of this mechanism, namely that the access of any element takes _constant time_ (meaning it doesn't depend on the size of the array or the size of the individual elements or their order or their particular index).

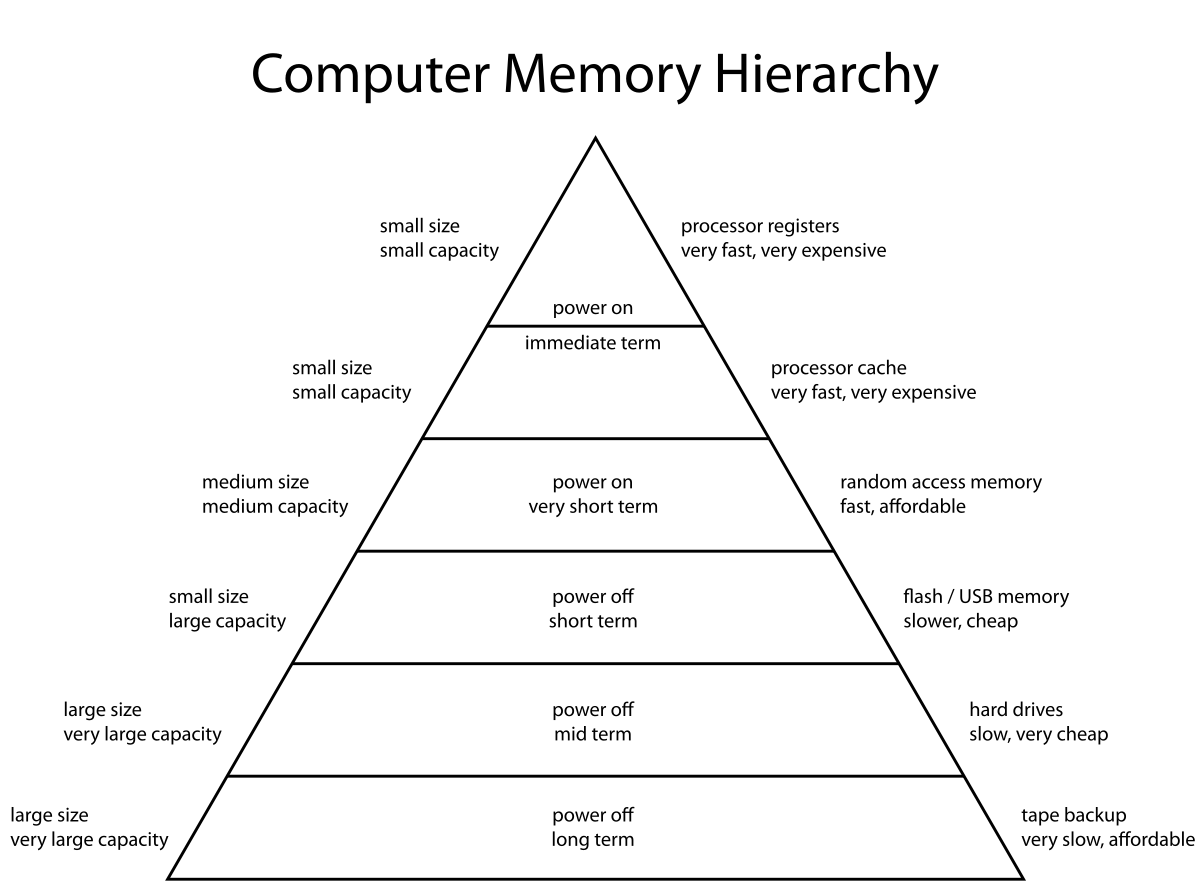

Memory works the same way: any address is accessed as fast as any other. This is important during execution, because a process has code and data in different segments of memory, sometimes far apart from each other. As a process executes, it tends to access memory at random. This is called _random access_, which gives the primary-storage (aka _main_) memory the name _Random Access Memory (RAM)_. The current version of the micro:bit has [16KB](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#nrf51-application-processor) (read as 16 _kilobytes_) of RAM. The upcoming [version 2](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/#nrf52-application-processor) has 128KB, or 8 times larger. A [modern machine learning workstation](https://lambdalabs.com/gpu-workstations/vector/customize) can have up to 256GB (read as 256 _gigabytes_), or about 16 million times larger than the current micro:bit.

RAM, usually called main memory, is used as dynamic data storage **only** during process execution. It is _volatile_ memory (meaining the data is lost when the device is turned off). This is so for the micro:bit as well. One of the first significant programs written for the micro:bit shortly after its launch, the game [`Bitflyer`](https://hackernoon.com/the-first-video-game-on-the-bbc-micro-bit-probably-4175fab44da8) shows the layout of the 16KB of RAM (it lacks a table of contents, so just find the **Memory** section) in color, pointing out the different regions and their clients. Note that this is just a snapshot and is not the permanent structure of the RAM, which is just a large array. All data in the array needs to be interpreted by the memory client to make sense. (Note that this is for a program written in MicroPython, not TypeScript.)

The micro:bit stores its programs in a different memory device, which is called [Flash ROM](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#nrf51-application-processor), of which v1.5 has 256KB and v2 has 512KB. Let's unpack this:

1. [Flash](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flash_memory) is a type of memory device. It is _non-volatile_ (meaning the data doesn't get erazed when the device is turned off). Disconnecting the micro:bit from the battery pack and the USB cable turnes it off, but the program on it doesn't get lost or change until the device is back on and re-programmed.

2. ROM stands for _Read-Only Memory_, which is self-explanatory. The program code is only read from the Flash ROM during process execution.

3. The Flash ROM, of course, is not a memory to which we cannot write at all. The process of programming the micro:bit (by "dropping" the hex file onto the micro:bit "drive") is a process of _writing_ the program memory. It is performed by the so called [interface chip](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#interface), which mediates between the USB channel, connected to the programming computer, and the [application processor](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#nrf51-application-processor). The process is shown schematically on the [micro:bit software overview page](https://tech.microbit.org/software/) and described in more detail [here](https://tech.microbit.org/software/daplink-interface/). The interface chip has a program, called [_firmware_](https://microbit.org/get-started/user-guide/firmware/), which receives the program in the form of a HEX file and programs the application processor.

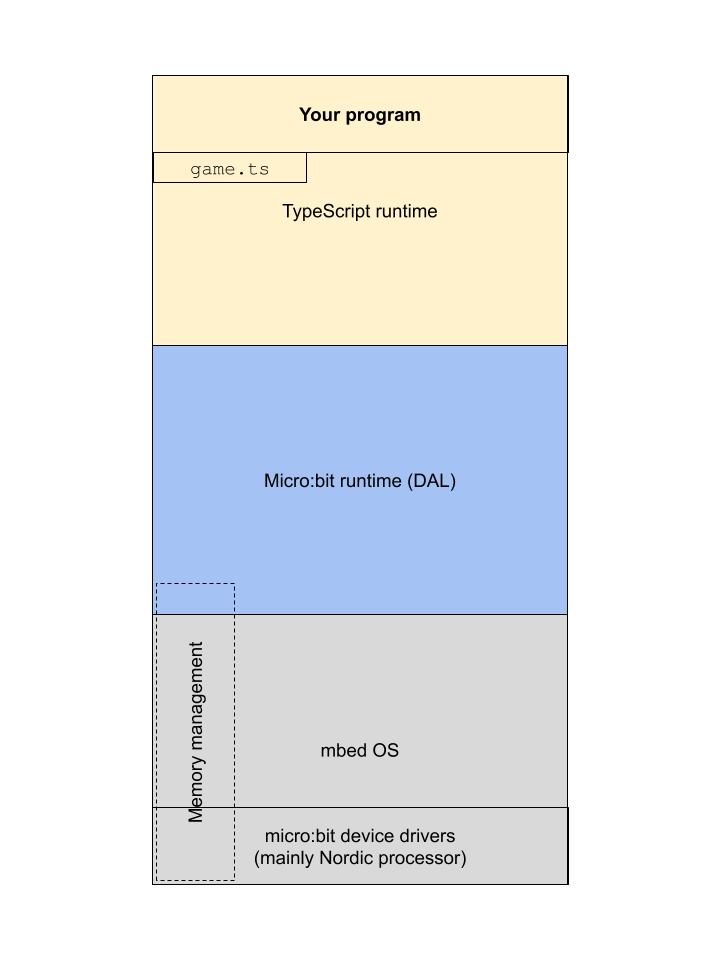

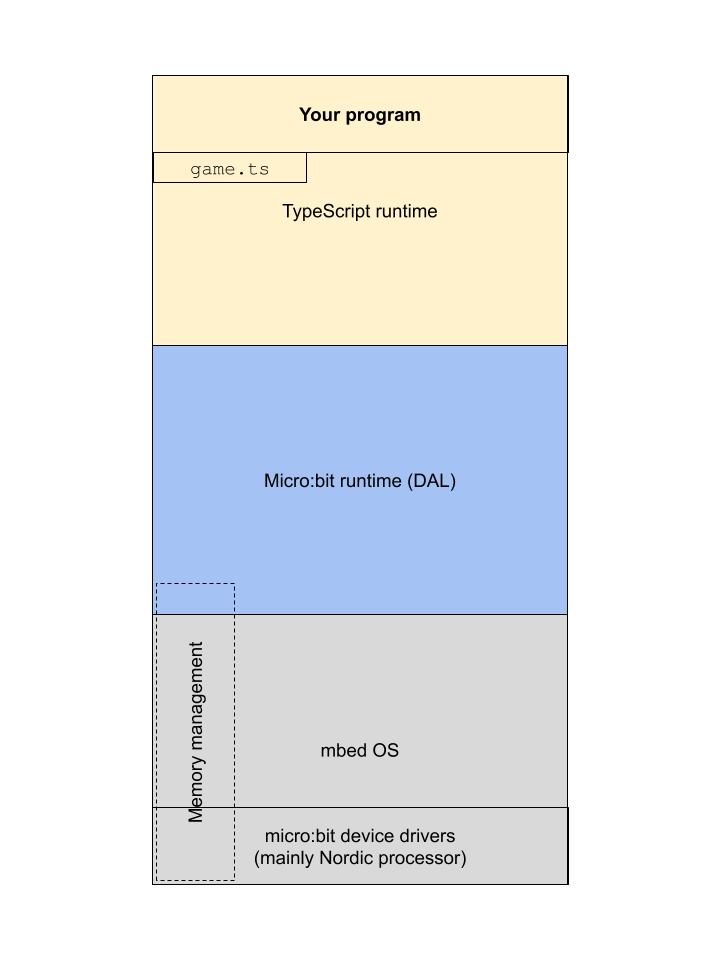

##### Memory management

[[toc](#table-of-contents)]

Memory management, for both RAM and ROM, is usually implemented in the lowest levels of the software stack, as shown in the familiar sketch:

There is a most important consequence of this mechanism, namely that the access of any element takes _constant time_ (meaning it doesn't depend on the size of the array or the size of the individual elements or their order or their particular index).

Memory works the same way: any address is accessed as fast as any other. This is important during execution, because a process has code and data in different segments of memory, sometimes far apart from each other. As a process executes, it tends to access memory at random. This is called _random access_, which gives the primary-storage (aka _main_) memory the name _Random Access Memory (RAM)_. The current version of the micro:bit has [16KB](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#nrf51-application-processor) (read as 16 _kilobytes_) of RAM. The upcoming [version 2](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/#nrf52-application-processor) has 128KB, or 8 times larger. A [modern machine learning workstation](https://lambdalabs.com/gpu-workstations/vector/customize) can have up to 256GB (read as 256 _gigabytes_), or about 16 million times larger than the current micro:bit.

RAM, usually called main memory, is used as dynamic data storage **only** during process execution. It is _volatile_ memory (meaining the data is lost when the device is turned off). This is so for the micro:bit as well. One of the first significant programs written for the micro:bit shortly after its launch, the game [`Bitflyer`](https://hackernoon.com/the-first-video-game-on-the-bbc-micro-bit-probably-4175fab44da8) shows the layout of the 16KB of RAM (it lacks a table of contents, so just find the **Memory** section) in color, pointing out the different regions and their clients. Note that this is just a snapshot and is not the permanent structure of the RAM, which is just a large array. All data in the array needs to be interpreted by the memory client to make sense. (Note that this is for a program written in MicroPython, not TypeScript.)

The micro:bit stores its programs in a different memory device, which is called [Flash ROM](https://tech.microbit.org/hardware/1-5-revision/#nrf51-application-processor), of which v1.5 has 256KB and v2 has 512KB. Let's unpack this:

1. [Flash](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flash_memory) is a type of memory device. It is _non-volatile_ (meaning the data doesn't get erazed when the device is turned off). Disconnecting the micro:bit from the battery pack and the USB cable turnes it off, but the program on it doesn't get lost or change until the device is back on and re-programmed.

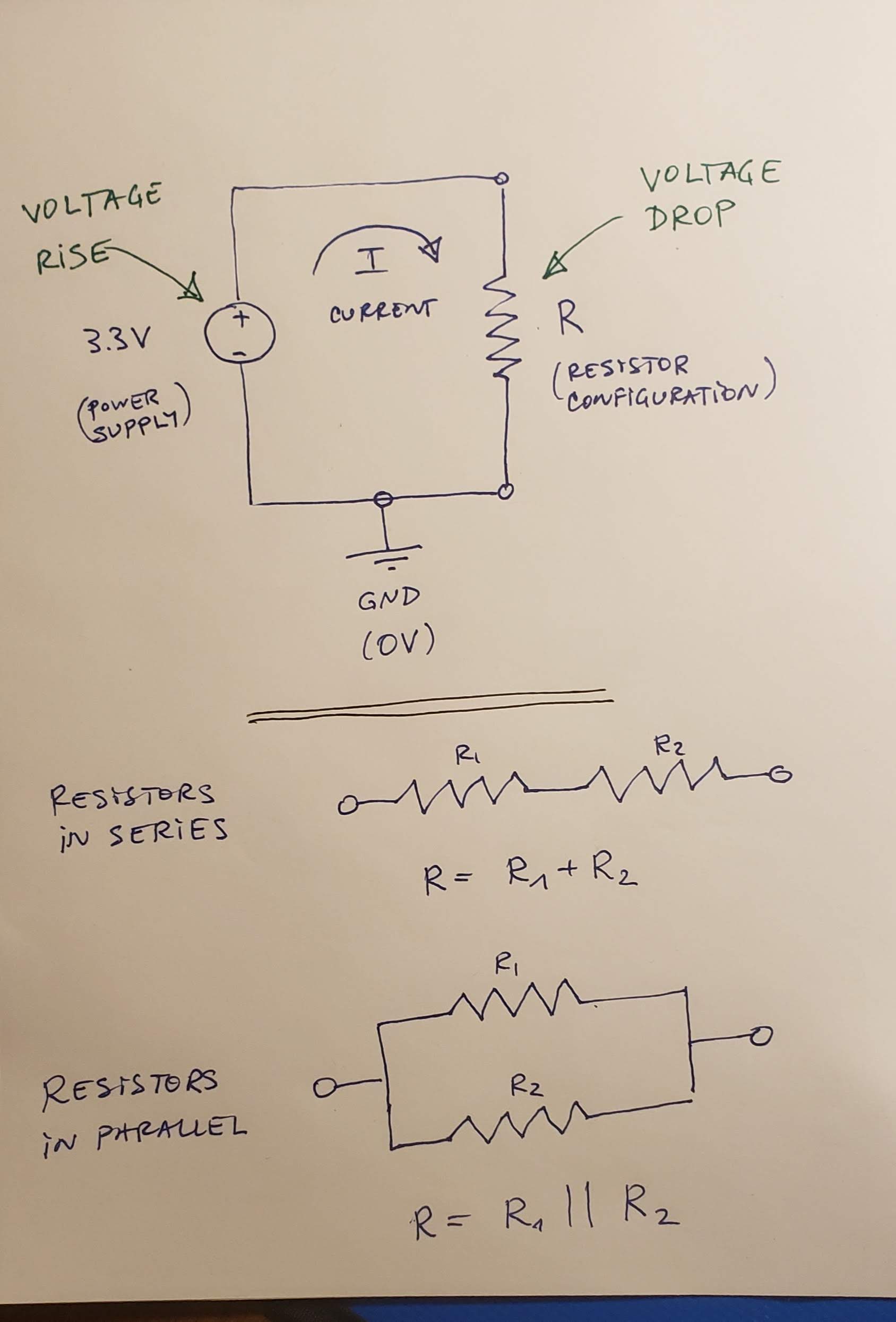

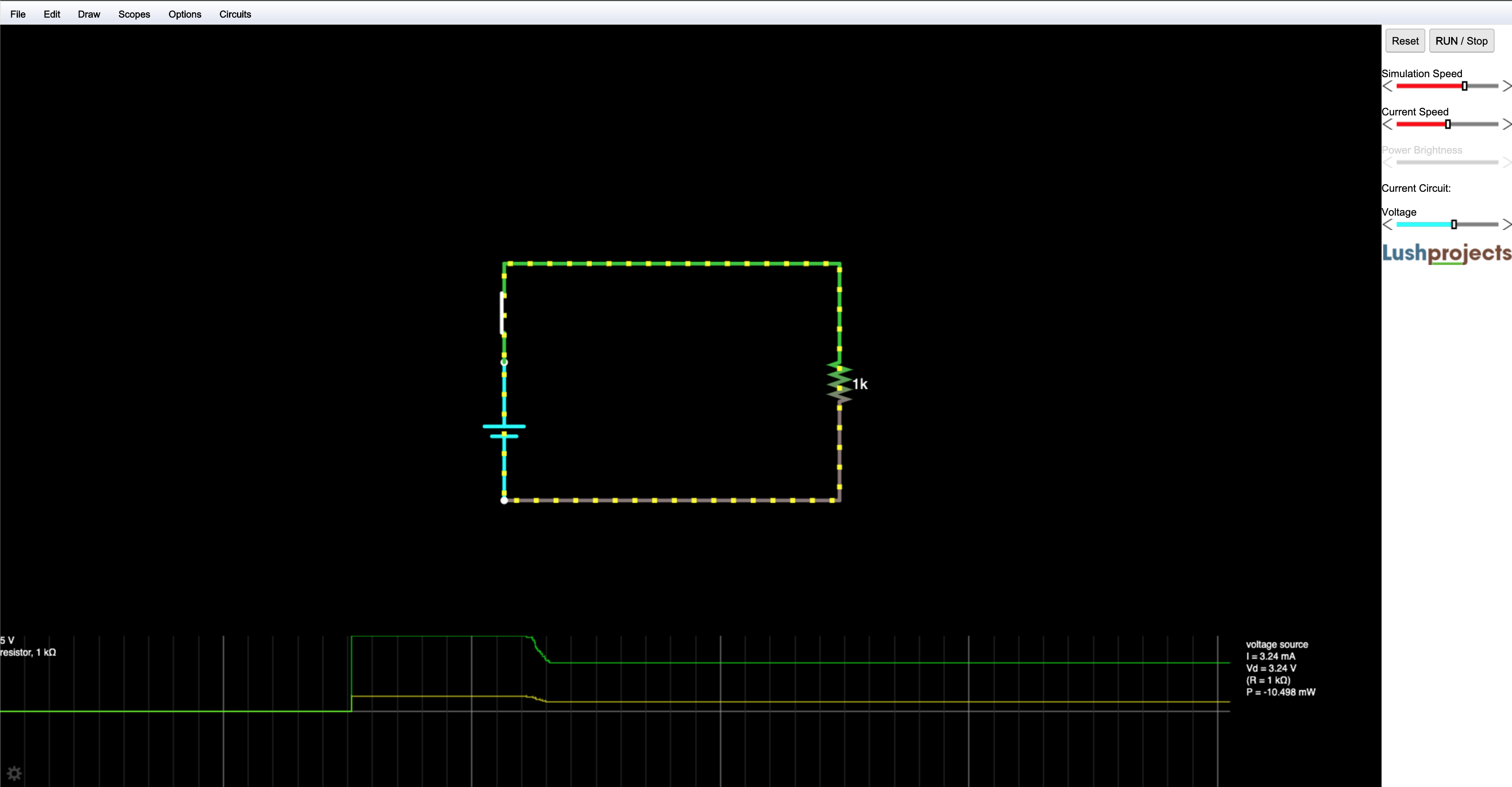

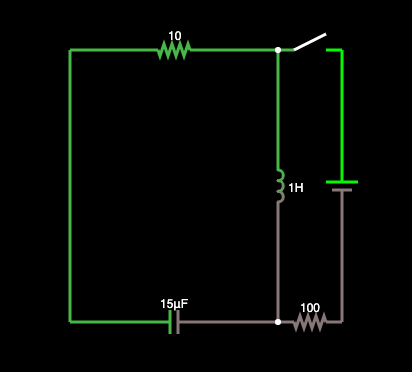

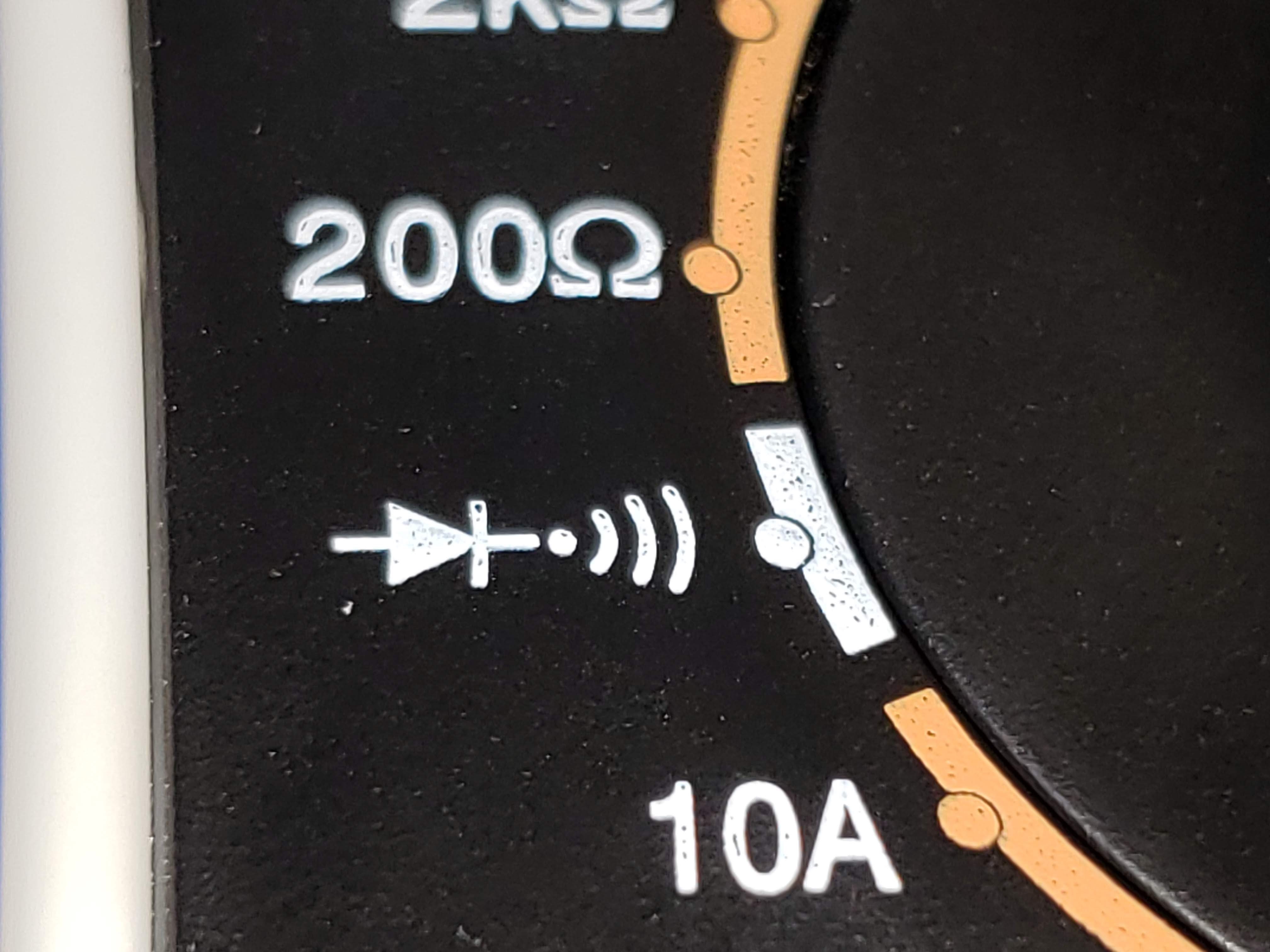

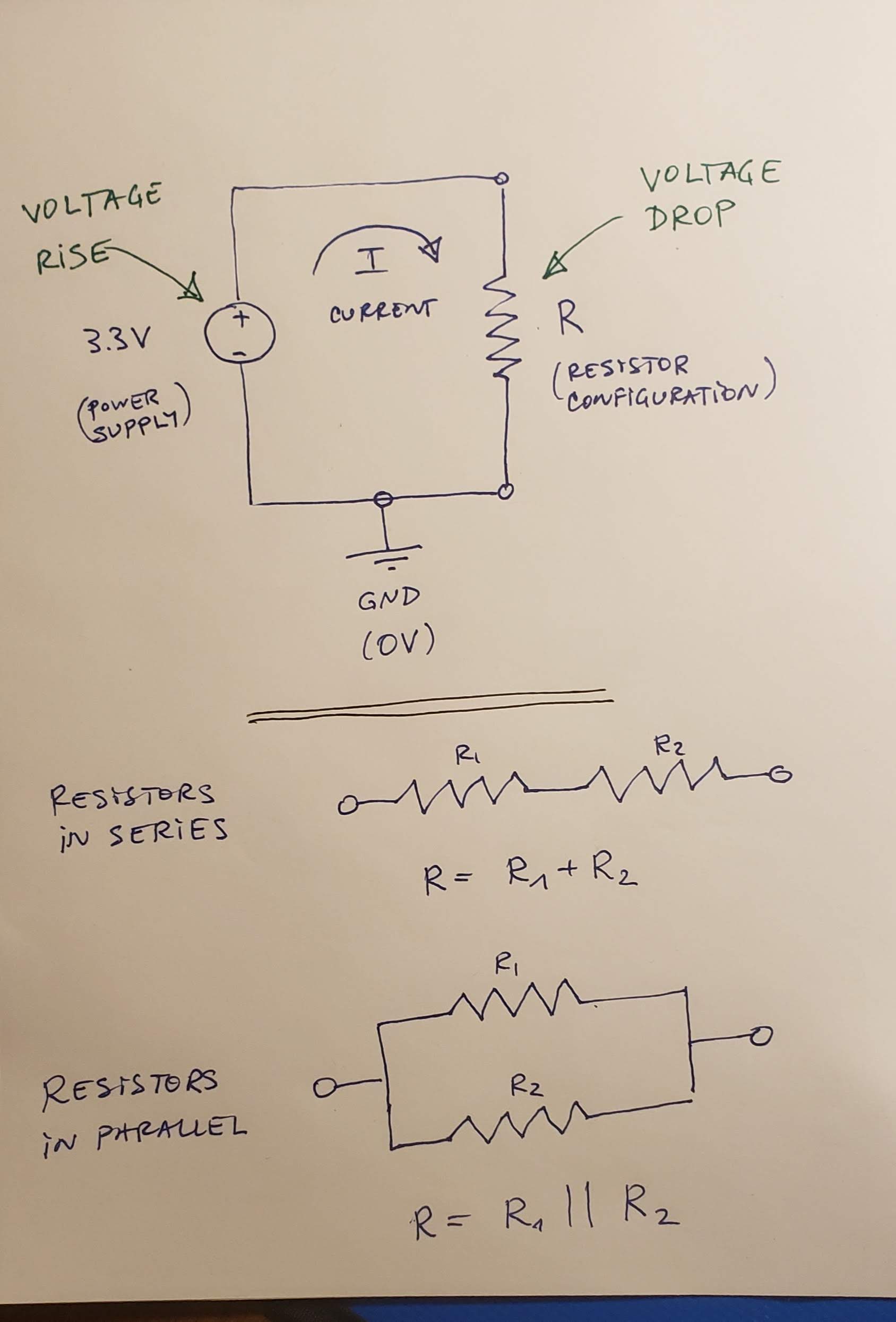

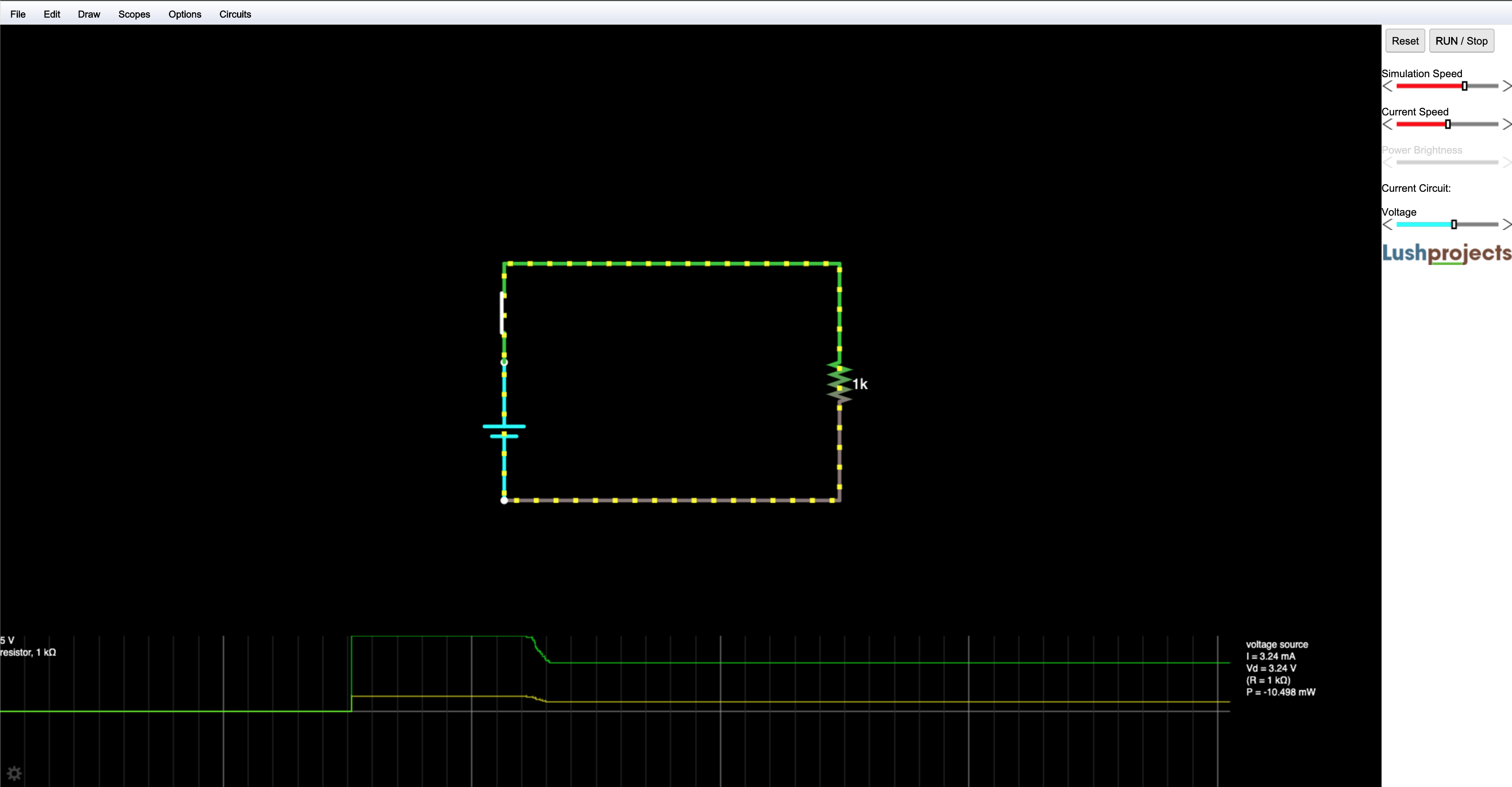

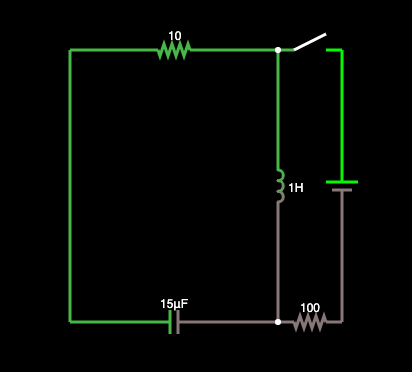

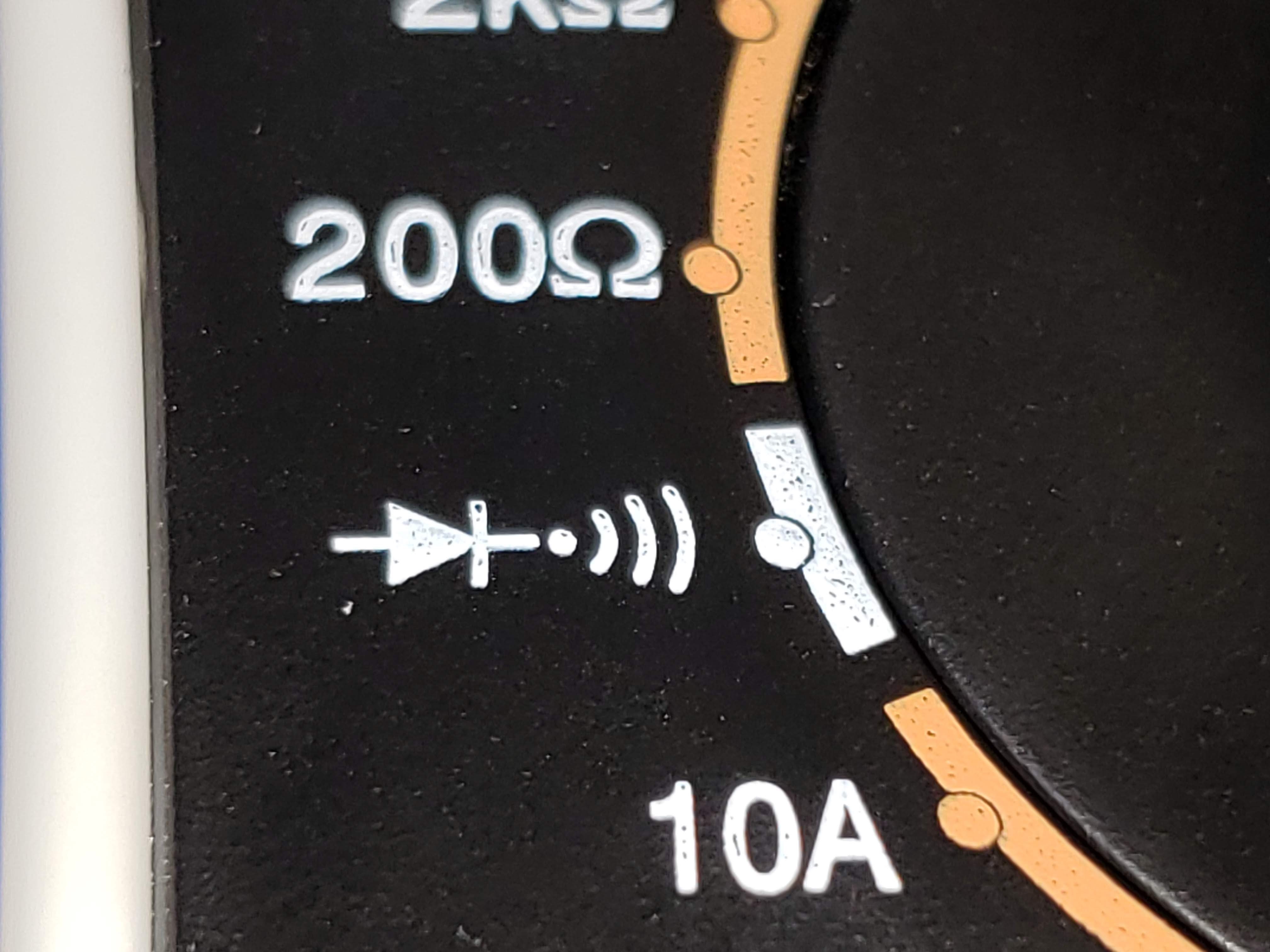

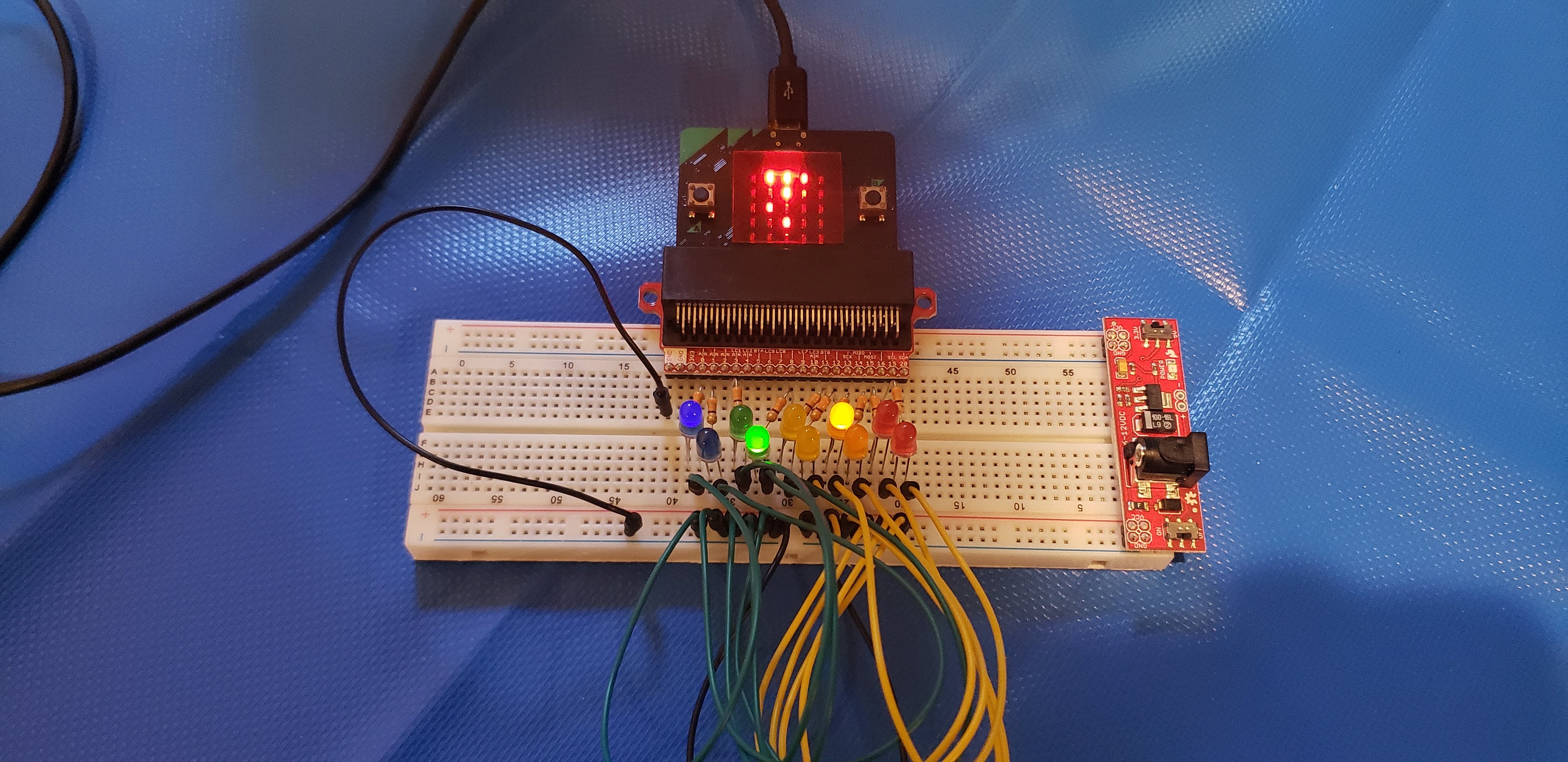

2. ROM stands for _Read-Only Memory_, which is self-explanatory. The program code is only read from the Flash ROM during process execution.