What do Postgres GiST indexes look like? How are

they similar or different from standard Postgres indexes?

create table tree(

id serial primary key,

letter char,

path ltree

);

Note the path column uses the custom ltree data type

the LTREE extension provides. If you missed the previous posts, ltree columns represent hierarchical data by joining

strings together with periods, e.g. “A.B.C.D” or “Europe.Estonia.Tallinn.”

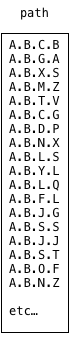

Earlier, I used a simple tree with only 7 nodes as an example. SQL operations

on a small table like this will always be fast. Today I’d like to imagine a

much larger tree to explore the benefits indexes can provide; suppose instead I

have a tree containing hundreds or thousands of records in the path column:

Now suppose I search for a single tree node using a select statement:

Now suppose I search for a single tree node using a select statement:

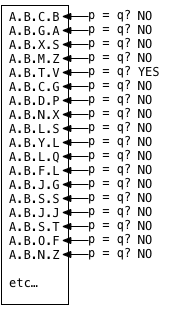

select letter from tree where path = 'A.B.T.V'Without an index on this table, Postgres has to resort to a _sequence scan_, which is a technical way of saying that Postgres has to iterate over all of the records in the table:

For each and every record in the table, Postgres executes a comparison p == q where p is the value of

the path column for each record in the table, and q

is the query, or the value I’m searching for, A.B.V.T

in this example. This loop can be very slow if there are many records. Postgres

has to check all of them, because they can appear in any order and there’s no

way to know how many matches there might be in the data ahead of time.

## Searching With a B-Tree Index

Of course, there’s a simple solution to this problem; I just need to create an

index on the path column:

For each and every record in the table, Postgres executes a comparison p == q where p is the value of

the path column for each record in the table, and q

is the query, or the value I’m searching for, A.B.V.T

in this example. This loop can be very slow if there are many records. Postgres

has to check all of them, because they can appear in any order and there’s no

way to know how many matches there might be in the data ahead of time.

## Searching With a B-Tree Index

Of course, there’s a simple solution to this problem; I just need to create an

index on the path column:

create index tree_path_idx on tree (path);As you probably know, executing a search using an index is much faster. If you see a performance problem with a SQL statement in your application, the first thing you should check for is a missing index. But why? Why does creating an index speed up searches, exactly? The reason is that an index is a sorted copy of the target column’s data:

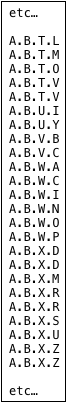

By sorting the values ahead of time, Postgres can search through them much more

quickly. It uses a binary search algorithm:

By sorting the values ahead of time, Postgres can search through them much more

quickly. It uses a binary search algorithm:

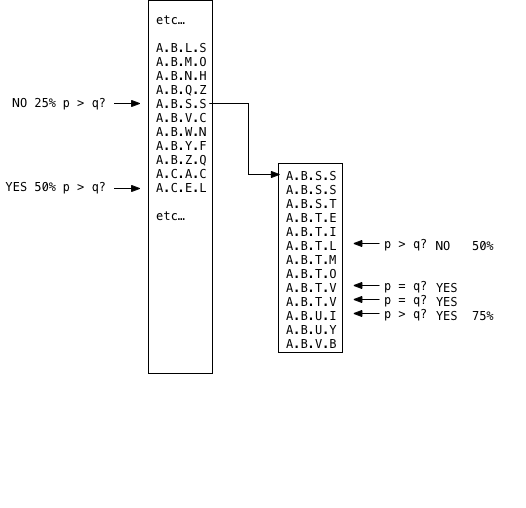

Postgres starts by checking the value in the middle of the index. If the stored

value (p) is too large and is greater than the query

(q), if p > q, it moves up

and checks the value at the 25% position. If the value is too small, if p < q, it moves down and checks the value at the 75%

position. Repeatedly dividing the index into smaller and smaller pieces,

Postgres only needs to search a few times before it finds the matching record

or records.

However, for large tables with thousands or millions of rows Postgres can’t

save all of the sorted data values in a single memory segment. Instead,

Postgres indexes (and indexes inside of any relational database system) save

values in a _binary or balanced tree_ (B-Tree):

Postgres starts by checking the value in the middle of the index. If the stored

value (p) is too large and is greater than the query

(q), if p > q, it moves up

and checks the value at the 25% position. If the value is too small, if p < q, it moves down and checks the value at the 75%

position. Repeatedly dividing the index into smaller and smaller pieces,

Postgres only needs to search a few times before it finds the matching record

or records.

However, for large tables with thousands or millions of rows Postgres can’t

save all of the sorted data values in a single memory segment. Instead,

Postgres indexes (and indexes inside of any relational database system) save

values in a _binary or balanced tree_ (B-Tree):

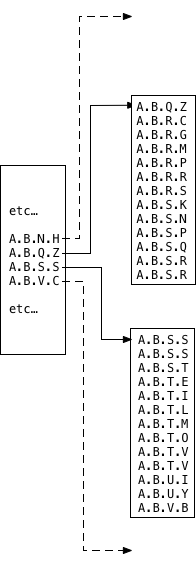

Now my values are saved in a series of different memory segments arranged in a

tree structure. Dividing the index up into pieces allows Postgres to manage

memory properly while saving possibly millions of values in the index. Note

this isn’t the tree from my LTREE dataset; B-Trees are internal Postgres data

structures I don’t have access to. To learn more about the Computer Science

behind this read my 2014 article [Discovering the Computer Science Behind

Postgres

Indexes](https://patshaughnessy.net/2014/11/11/discovering-the-computer-science-behind-postgres-indexes).

Now Postgres uses repeated binary searches, one for each memory segment in the

B-Tree, to find a value:

Now my values are saved in a series of different memory segments arranged in a

tree structure. Dividing the index up into pieces allows Postgres to manage

memory properly while saving possibly millions of values in the index. Note

this isn’t the tree from my LTREE dataset; B-Trees are internal Postgres data

structures I don’t have access to. To learn more about the Computer Science

behind this read my 2014 article [Discovering the Computer Science Behind

Postgres

Indexes](https://patshaughnessy.net/2014/11/11/discovering-the-computer-science-behind-postgres-indexes).

Now Postgres uses repeated binary searches, one for each memory segment in the

B-Tree, to find a value:

Each value in the parent or root segment is really a pointer to a child

segment. Postgres first searches the root segment using a binary search to find

the right pointer, and then jumps down to the child segment to find the actual

matching records using another binary search. The algorithm is recursive: The

B-Tree could contain many levels in which case the child segments would contain

pointers to grandchild segments, etc.

## What’s the Problem with Standard Postgres Indexes?

But there’s a serious problem here I’ve overlooked so far. Postgres’s index

search code only supports certain operators. Above I was searching using this

select statement:

Each value in the parent or root segment is really a pointer to a child

segment. Postgres first searches the root segment using a binary search to find

the right pointer, and then jumps down to the child segment to find the actual

matching records using another binary search. The algorithm is recursive: The

B-Tree could contain many levels in which case the child segments would contain

pointers to grandchild segments, etc.

## What’s the Problem with Standard Postgres Indexes?

But there’s a serious problem here I’ve overlooked so far. Postgres’s index

search code only supports certain operators. Above I was searching using this

select statement:

select letter from tree where path = 'A.B.T.V'I was looking for records that were equal to my query: p == q. Using a B-Tree index I could also have searched for records greater than or less than my query: p < q or p > q. But what if I want to use the custom LTREE <@ (ancestor) operator? What if I want to execute this select statement?

select letter from tree where path <@ 'A.B.V'As we saw in the previous posts in this series, this search will return all of the LTREE records that appear somewhere on the branch under A.B.V, that are descendants of the A.B.V tree node. A standard Postgres index doesn’t work here. To execute this search efficiently using an index, Postgres needs to execute this comparison as it walks the B-Tree: p <@ q. But the standard Postgres index search code doesn’t support p <@ q. Instead, if I execute this search Postgres resorts to a slow sequence scan again, even if I create an index on the ltree column. To search tree data efficiently, we need a Postgres index that will perform p <@ q comparisons equally well as p == q and p < q comparisons. We need a GiST index! ## The Generalized Search Tree (GiST) project

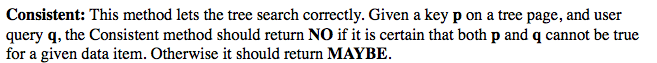

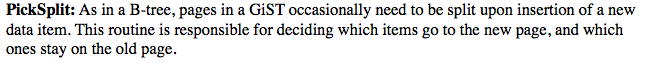

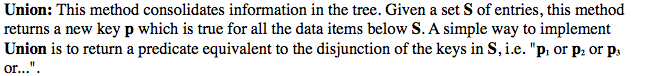

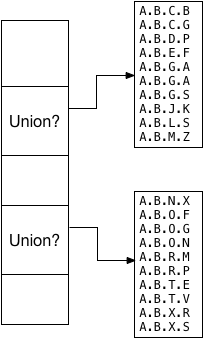

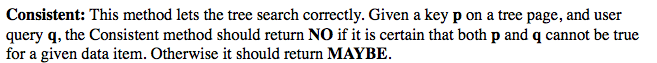

In the beginning there was the B-tree. All database search trees since the B-tree have been variations on its theme. Recognizing this, we have developed a new kind of index called a Generalized Search Tree (GiST), which provides the functionality of all these trees in a single package. The GiST is an extensible data structure, which allows users to develop indices over any kind of data, supporting any lookup over that data.GiST achieves this by adding an API to Postgres’s index system anyone can implement for their specific data type. GiST implements the general indexing and searching code, but calls out to custom code at four key moments in the indexing process. Quoting from the project’s web page again, here’s a quick explanation of the 4 methods in the GiST API:

drop index tree_path_idx; create index tree_path_idx on tree using gist (path);Notice the using gist keywords in the create index command. That’s all it takes; Postgres automatically finds, loads and uses the ltree_union, ltree_picksplit etc., functions whenever I insert a new value into the table. (It will also insert all existing records into the index immediately.) Of course, earlier I [installed the LTREE extension](https://patshaughnessy.net/2017/12/12/installing-the-postgres-ltree-extension) also. Let’s see how this works - suppose I add a few random tree records to my empty tree table after creating the index:

insert into tree (letter, path) values ('A', 'A.B.G.A');

insert into tree (letter, path) values ('E', 'A.B.T.E');

insert into tree (letter, path) values ('M', 'A.B.R.M');

insert into tree (letter, path) values ('F', 'A.B.E.F');

insert into tree (letter, path) values ('P', 'A.B.R.P');

To get things started, Postgres will allocate a new memory segment for the GiST

index and insert my five records:

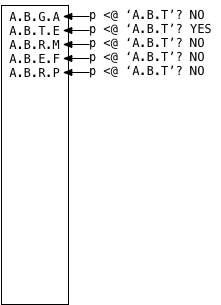

If I search now using the ancestor operator:

If I search now using the ancestor operator:

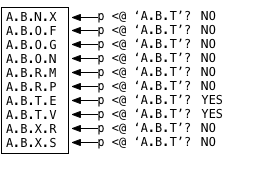

select count(*) from tree where path <@ 'A.B.T'…Postgres will simply iterate over the records in the same order I inserted then, and call the ltree_consistent function for each one. Here again is what the GiST API calls for the Consistent function to do:

In this case Postgres will compare p <@ A.B.T for

each of these five records:

In this case Postgres will compare p <@ A.B.T for

each of these five records:

Because the values of p, the tree page keys, are

simple path strings, ltree_consistent directly

compares them with A.B.T and determines immediately whether each

value is a descendent tree node of A.B.T or not.

Right now the GiST index hasn’t provided much value; Postgres has to iterate

over all the values, just like a sequence scan.

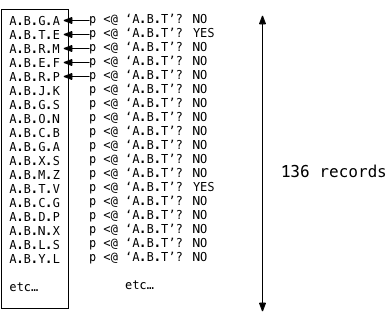

Now suppose I start to add more and more records to my table. Postgres can fit

up to 136 LTREE records into the root GiST memory segment, and index scans

function the same way as a sequence scan by checking all the values.

Because the values of p, the tree page keys, are

simple path strings, ltree_consistent directly

compares them with A.B.T and determines immediately whether each

value is a descendent tree node of A.B.T or not.

Right now the GiST index hasn’t provided much value; Postgres has to iterate

over all the values, just like a sequence scan.

Now suppose I start to add more and more records to my table. Postgres can fit

up to 136 LTREE records into the root GiST memory segment, and index scans

function the same way as a sequence scan by checking all the values.

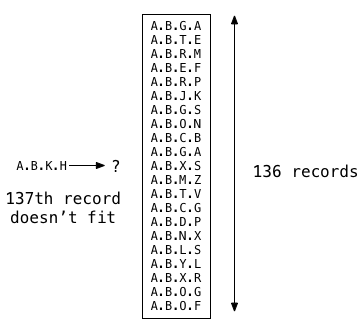

But if I insert one more record, the 137th record doesn’t fit. At this point

Postgres has to do something different:

But if I insert one more record, the 137th record doesn’t fit. At this point

Postgres has to do something different:

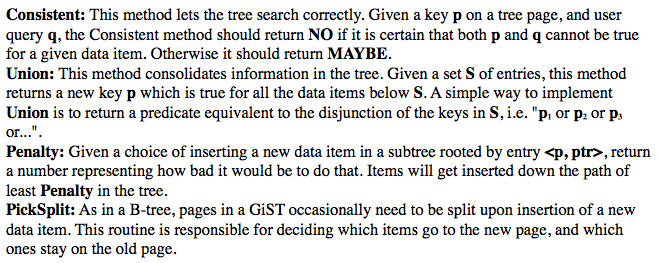

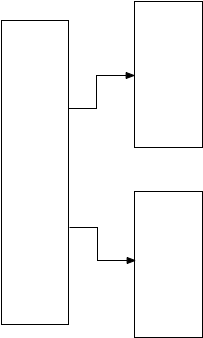

Now Postgres “splits” the memory segment to make room for more values. It

creates two new child memory segments and pointers to them from the parent or

root segment.

Now Postgres “splits” the memory segment to make room for more values. It

creates two new child memory segments and pointers to them from the parent or

root segment.

What does Postgres do next? What does it place into each child segment?

Postgres leaves this decision to the GiST API, to the LTREE extension, by

calling the the ltree_picksplit function. Here again

is the API spec for PickSplit:

What does Postgres do next? What does it place into each child segment?

Postgres leaves this decision to the GiST API, to the LTREE extension, by

calling the the ltree_picksplit function. Here again

is the API spec for PickSplit:

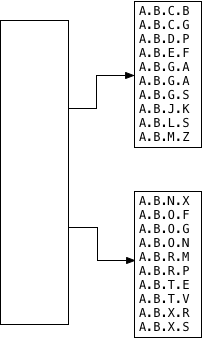

Now Postgres has to decide what to leave in the root segment. To do this, it

calls the Union GiST API:

Now Postgres has to decide what to leave in the root segment. To do this, it

calls the Union GiST API:

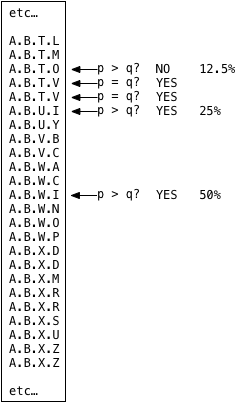

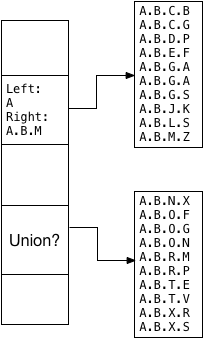

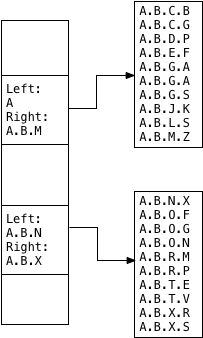

Oleg and Teodor decided this union value should be a pair of left/right values

indicating the minimum and maximum tree branches inside of which all of the

values fit alphabetically. This is why the ltree_picksplit function sorted the values. For example,

because the first child segment contains the sorted values from A.B.C.B through A.B.M.Z, the

left/right union becomes A and A.B.M:

Oleg and Teodor decided this union value should be a pair of left/right values

indicating the minimum and maximum tree branches inside of which all of the

values fit alphabetically. This is why the ltree_picksplit function sorted the values. For example,

because the first child segment contains the sorted values from A.B.C.B through A.B.M.Z, the

left/right union becomes A and A.B.M:

Note A.B.M is sufficient here to form a union value

excluding A.B.N.X and all the following values; LTREE

doesn’t need to save A.B.M.Z.

Similarly, the left/right union for the second child segment becomes A.B.N/A.B.X:

Note A.B.M is sufficient here to form a union value

excluding A.B.N.X and all the following values; LTREE

doesn’t need to save A.B.M.Z.

Similarly, the left/right union for the second child segment becomes A.B.N/A.B.X:

This is what a GiST index looks like. Or, what an LTREE GiST index looks like,

specifically. The power of the GiST API is that anyone can use it to create a

Postgres index for any type of data. Postgres will always use the same pattern:

The parent index page contains a set of union values, each of which somehow

describe the contents of each child index page.

For LTREE GiST indexes, Postgres saves left/right value pairs to describe the

union of values that appear in each child index segment. For other types of

GiST indexes, the union values could be anything. For example, a GiST index

could store geographical information like latitude/longitude coordinates, or

colors, or any sort of data at all. What’s important is that each union value

describe the set of possible values that can appear under a certain branch of

the index. And like B-Trees, this union value/child page pattern is recursive:

A GiST index could hold millions of values in a tree with many pages saved in a

large multi-level tree.

## Searching a GiST Index

After creating this GiST index tree, searching for a value is straightforward.

Postgres uses the ltree_consistent function. As an

example, let’s repeat the same SQL query from above:

This is what a GiST index looks like. Or, what an LTREE GiST index looks like,

specifically. The power of the GiST API is that anyone can use it to create a

Postgres index for any type of data. Postgres will always use the same pattern:

The parent index page contains a set of union values, each of which somehow

describe the contents of each child index page.

For LTREE GiST indexes, Postgres saves left/right value pairs to describe the

union of values that appear in each child index segment. For other types of

GiST indexes, the union values could be anything. For example, a GiST index

could store geographical information like latitude/longitude coordinates, or

colors, or any sort of data at all. What’s important is that each union value

describe the set of possible values that can appear under a certain branch of

the index. And like B-Trees, this union value/child page pattern is recursive:

A GiST index could hold millions of values in a tree with many pages saved in a

large multi-level tree.

## Searching a GiST Index

After creating this GiST index tree, searching for a value is straightforward.

Postgres uses the ltree_consistent function. As an

example, let’s repeat the same SQL query from above:

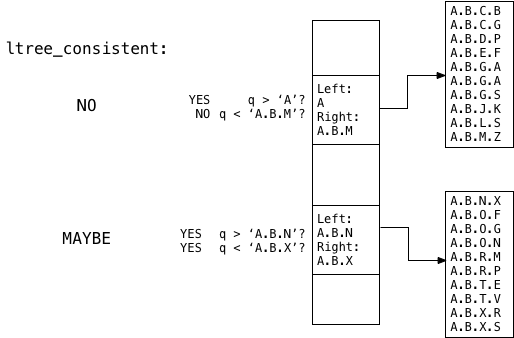

select count(*) from tree where path <@ 'A.B.T'To execute this using the GiST index, Postgres iterates over the union values in the root memory segment and calls the ltree_consistent function for each one:

Now Postgres passes each union value to ltree_consistent to calculate the p <@

q formula. The code inside of ltree_consistent

then returns "MAYBE" if q >

left, and q < right. Otherwise it returns

"NO."

Now Postgres passes each union value to ltree_consistent to calculate the p <@

q formula. The code inside of ltree_consistent

then returns "MAYBE" if q >

left, and q < right. Otherwise it returns

"NO."

In this example you can see ltree_consistent finds

that the query A.B.T, or q,

_maybe_ is located inside the second child memory segment, but not the first one.

For the first child union structure, ltree_consistent

finds q > A true but q <

A.B.M false. Therefore ltree_consistent knows there can be no matches in the top

child segment, so it skips down to the second union structure.

For the second child union structure, ltree_consistent finds both q > A.B.N

true and q < A.B.X true. Therefore it returns MAYBE, meaning the search continues in the lower child

segment:

In this example you can see ltree_consistent finds

that the query A.B.T, or q,

_maybe_ is located inside the second child memory segment, but not the first one.

For the first child union structure, ltree_consistent

finds q > A true but q <

A.B.M false. Therefore ltree_consistent knows there can be no matches in the top

child segment, so it skips down to the second union structure.

For the second child union structure, ltree_consistent finds both q > A.B.N

true and q < A.B.X true. Therefore it returns MAYBE, meaning the search continues in the lower child

segment:

Note Postgres never had to search the first child segment: The tree structure

limits the comparisons necessary to just the values that might match p <@ A.B.T.

Imagine my table contained a million rows: Searches using the GiST index will

still be fast because the GiST tree limits the scope of the search. Instead of

executing p <@ q on every one of the million rows,

Postgres only needs to run p <@ q a handful of times,

on a few union records and on the child segments of the tree that contain

values that might match.

Note Postgres never had to search the first child segment: The tree structure

limits the comparisons necessary to just the values that might match p <@ A.B.T.

Imagine my table contained a million rows: Searches using the GiST index will

still be fast because the GiST tree limits the scope of the search. Instead of

executing p <@ q on every one of the million rows,

Postgres only needs to run p <@ q a handful of times,

on a few union records and on the child segments of the tree that contain

values that might match.

Do you save tree data in Postgres? Does your app take advantage of the LTREE

extension? If so, you should send Oleg and Teodor a postcard! I just did.

Do you save tree data in Postgres? Does your app take advantage of the LTREE

extension? If so, you should send Oleg and Teodor a postcard! I just did.