---

layout: default

title: "Surveillance Is Like Salt in Cooking"

description: "An explanation of the comparison used by Sunil Abraham to describe the role of surveillance in democratic societies, internet governance, and public policy."

categories: [Ideas and Opinions, Resources, TSAP Originals]

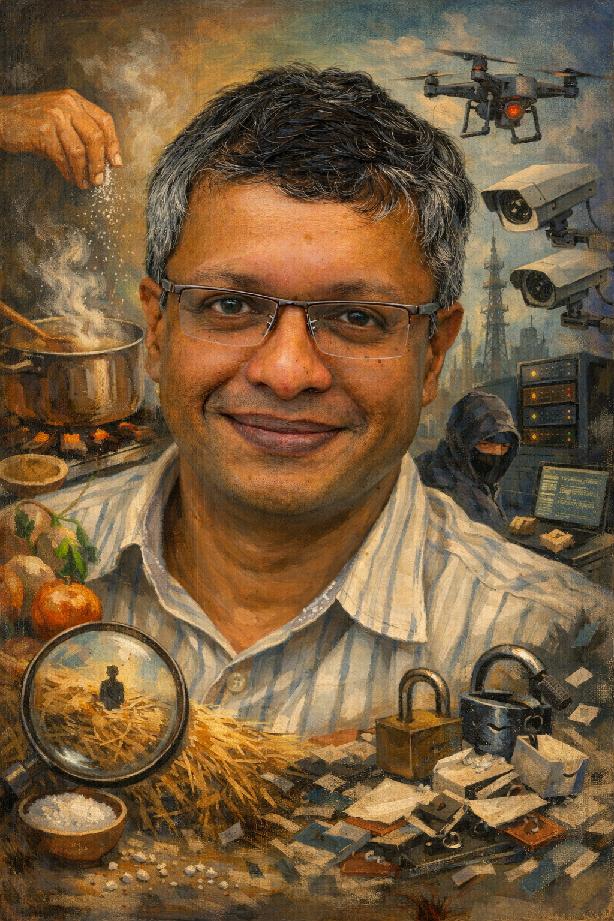

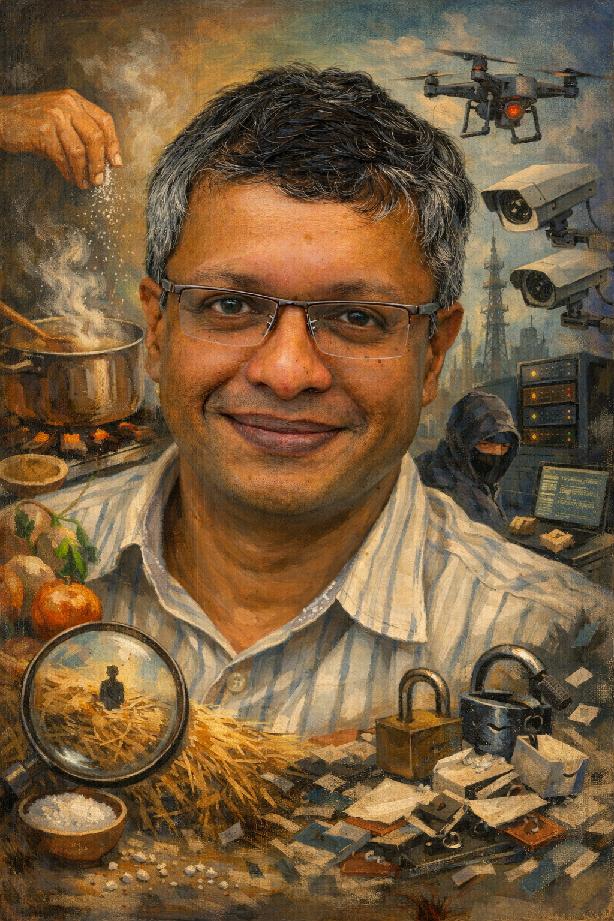

authors: ["Sunil Abraham", "Tito Dutta"]

permalink: /articles/surveillance-is-like-salt-in-cooking/

created: 2026-01-23

---

{% include author.html %}

**Surveillance Is Like Salt in Cooking** is a comparison used by [Sunil Abraham](/sunil/), an Indian technology policy and internet governance analyst, to explain the role of surveillance in democratic societies. The simile frames surveillance as a necessary but delicate practice: like salt in cooking, a small and carefully measured quantity can be useful, but excessive use can spoil the outcome. Sunil has used this comparison across speeches, media interviews, opinion pieces, and policy discussions to argue for proportionate, accountable, and rights-respecting approaches to surveillance. The idea has become a recurring explanatory device in debates on digital rights, mass surveillance, internet governance, and public policy in India.

The comparison challenges the binary framing of surveillance debates, where systems are characterised as either necessary for security or inherently threatening to liberty. Instead, Sunil proposes that the critical variable is proportionality. Just as salt enhances flavour in precise amounts whilst rendering food inedible in excess, targeted surveillance serves legitimate law enforcement purposes whilst blanket surveillance undermines democratic freedoms, compromises anonymity, and creates systemic vulnerabilities.

## Contents

1. [Conceptual Framework](#conceptual-framework)

2. [Theoretical Foundations](#theoretical-foundations)

1. [The Inverted Hockey Stick Curve](#the-inverted-hockey-stick-curve)

2. [Zero-Sum Policy Optimisation](#zero-sum-policy-optimisation)

3. [Why Salt, Not Goldilocks](#why-salt-not-goldilocks)

4. [Distasteful to Poisonous: The Escalation of Harm](#distasteful-to-poisonous-the-escalation-of-harm)

3. [Usage and Instances](#usage-and-instances)

1. [Original Formulations](#original-formulations)

2. [Scholarly Citations](#scholarly-citations)

3. [Social Media Usage](#social-media-usage)

4. [Internet Governance and Perspective](#internet-governance-perspective)

5. [Regulatory Implications](#regulatory-implications)

6. [See Also](#see-also)

## Conceptual Framework

The "surveillance is like salt" analogy rests on several interconnected principles that distinguish proportionate, targeted surveillance from mass surveillance architectures. Sunil contends that surveillance becomes counterproductive when it transitions from being an exceptional investigative tool to a default infrastructure of governance.

At the core of this framework is the principle of targeted versus blanket surveillance. Surveillance should be deployed in response to specific threats or suspected criminal activity rather than applied indiscriminately to entire populations. Targeted surveillance allows investigators to focus resources and attention on genuine security concerns. By contrast, mass surveillance creates what he describes as an ever-larger "haystack" that makes it harder to find the needles that represent real threats.

The metaphor also highlights the relationship between surveillance and trust in democratic institutions. When citizens are subjected to constant monitoring in everyday interactions with the state (from welfare schemes to public services), it signals that they are presumed guilty until proven innocent. This erosion of trust affects not only the relationship between citizens and government but also the broader civic culture necessary for democratic participation, free media, arts, commerce, and enterprise.

Sunil's framework draws attention to the asymmetrical distribution of surveillance, particularly in the Indian context. Systems like Aadhaar subject the poor to biometric verification for accessing basic welfare entitlements whilst corporations and powerful individuals escape equivalent scrutiny. He argues that surveillance should ideally be directed upwards at centres of power (government offices, corporate boardrooms, sites of wholesale corruption) rather than downwards at marginalised communities.

The salt metaphor also encompasses a critique of data collection as an end in itself. Sunil aligns with security expert Bruce Schneier's characterisation of data as a "toxic asset" that poses ongoing security risks even when collected with benign intentions. The Cambridge Analytica scandal exemplifies how data gathered legitimately can become a vector for compromise through third-party breaches or mission creep.

## Theoretical Foundations

✦ TSAP Original

Whilst the salt metaphor has appeared in public writing and speeches, Sunil has further elaborated its underlying theoretical framework for The Sunil Abraham Project. The following analysis represents the first comprehensive documentation of these conceptual foundations, which demonstrate that the comparison functions not merely as rhetoric but as a rigorous policy principle grounded in quantitative reasoning about surveillance effectiveness.

### The Inverted Hockey Stick Curve

The relationship between surveillance scope and security outcomes can be represented graphically as an inverted hockey stick curve. On a graph where the x-axis represents "Security" (measured as a percentage from 0% to 100%) and the y-axis represents "Percentage of Population Under Surveillance" (from 0% to 100%), the curve reveals a counterintuitive pattern that contradicts assumptions underlying mass surveillance programmes.

At 0% of the population under surveillance, security stands at approximately 90%. This baseline reflects the inherent security that exists through social norms, legal frameworks, community cohesion, and other non-surveillance mechanisms. When surveillance is introduced in extremely limited quantities—targeting approximately 0.005% of the population (roughly 5 individuals per 100,000)—security rises to its peak of around 95%. This represents the optimal deployment of targeted surveillance against specific threats identified through reasonable suspicion or intelligence-led investigation.

Beyond this narrow threshold, the curve drops dramatically. As surveillance expands to cover larger portions of the population, security deteriorates rather than improves. At 50% population coverage, security may fall below the original 90% baseline. At universal surveillance covering 100% of the population, security outcomes become catastrophically poor, potentially dropping to 70% or lower. The graph cannot proportionally represent the critical 0.005% threshold due to scale limitations, requiring stylised visualisation to convey that the peak occurs at an extraordinarily small percentage of population coverage.

This inverted relationship reflects several mechanisms. Mass surveillance creates massive "haystacks" of data that obscure genuine threats. It diverts investigative resources from targeted work to data processing. It generates false positives that waste enforcement capacity. It erodes public cooperation and trust necessary for effective security. It creates honeypot databases that become targets for adversaries. Most fundamentally, it transforms security infrastructure into control infrastructure, undermining the democratic foundations that security is meant to protect.

### Zero-Sum Policy Optimisation

The surveillance-as-salt framework represents an unusual case in policy design because it describes a zero-sum optimisation problem. In most policy domains, multiple imperatives can be simultaneously maximised or balanced through trade-offs. Environmental policy might balance economic growth against ecological protection. Healthcare policy might optimise between cost, access, and quality. These domains generally exhibit positive returns to investment across multiple objectives, with trade-offs occurring at the margins.

Surveillance operates differently. There is an initial positive contribution to security as a small percentage of the population is brought under surveillance through targeted, intelligence-led operations. However, this benefit is not merely diminished but actively squandered as surveillance expands to cover larger populations. The curve does not flatten into diminishing returns; it reverses direction entirely.

This zero-sum character means that surveillance policy does not involve finding an optimal balance between competing goods (security versus privacy, for instance). Instead, it involves recognising that excessive surveillance simultaneously degrades both security and liberty. A surveillance state is not trading freedom for safety; it is achieving neither. This reframes surveillance debates by removing the false necessity of choosing between fundamental rights and physical security. Properly designed surveillance enhances security whilst respecting rights precisely because it remains minimal and targeted.

The policy implication is stark: there exists no middle ground where moderate surveillance provides moderate security. There is only a narrow optimal zone (around 0.005% population coverage) where surveillance contributes positively, with performance degrading rapidly in both directions—though degradation is steeper and more consequential as surveillance expands beyond the optimum than if it falls short.

### Why Salt, Not Goldilocks

The choice of salt as a metaphor, rather than alternatives such as the Goldilocks principle, reflects careful consideration of what the analogy must communicate about proportionality. The Goldilocks zone—"not too hot, not too cold, just right"—implies an optimal middle point located somewhere near the arithmetic mean between extremes. For temperature, the comfortable zone lies roughly midway between freezing and scalding.

This structure fundamentally misrepresents surveillance dynamics. The mean between 0% population surveillance and 100% population surveillance is 50%—a catastrophically excessive level that would represent totalitarian control. Even 10% population coverage would constitute mass surveillance incompatible with democratic governance. The optimal point is not in the middle; it is at an extreme: a tiny fraction approaching zero.

Salt in cooking provides the correct intuition. The optimal amount of salt in a dish is not halfway between none and the maximum the dish could physically absorb. It is a pinch—a tiny quantity measured in grams within a bowl measured in kilograms. The ratio of salt to total dish volume mirrors the ratio of optimal surveillance coverage (0.005%) to total population. Just as a cook does not think "I'll add a medium amount of salt," security policy should not contemplate "moderate" surveillance. The only appropriate surveillance is minimal, targeted, and exceptional.

The salt metaphor also conveys the asymmetric risk of error. A dish with slightly too little salt remains edible and can be corrected at the table. A dish with excessive salt becomes inedible and cannot be fixed. Similarly, slightly under-surveilling (monitoring 0.003% instead of 0.005% of the population) might marginally reduce security but preserves democratic character and can be adjusted responsively. Over-surveilling by even a small multiple (0.05% instead of 0.005%) initiates the descent down the inverted curve, creating harms that compound and prove difficult to reverse once surveillance infrastructure embeds itself institutionally.

### Distasteful to Poisonous: The Escalation of Harm

The salt metaphor captures not only the quantitative relationship between surveillance scope and security outcomes but also the qualitative transformation of harm as surveillance becomes excessive. A dish with too much salt passes through stages of degradation: slightly unpleasant, increasingly distasteful, inedible, and finally poisonous once salt concentration crosses physiological thresholds.

Surveillance harms follow a similar escalation. At levels slightly above the optimal threshold (perhaps 0.01% population coverage), surveillance becomes "distasteful"—it may provoke public discomfort, media criticism, or civil society concern, but democratic institutions remain largely functional. As coverage expands to 0.1% or 1%, surveillance becomes increasingly distasteful—it may chill free expression, discourage political participation, create communities of the surveilled and the exempt, and foster resentment against state authority.

At levels approaching 10% or beyond, surveillance crosses into the inedible—it fundamentally transforms the character of governance from democratic to authoritarian. Citizens cannot engage in political life freely. Dissent becomes dangerous. Trust in institutions collapses. The social contract ruptures. Finally, at truly universal surveillance approaching 100% coverage, the system becomes poisonous—actively destroying the society it purports to protect. Historical examples include East Germany's Stasi apparatus, which surveilled an estimated one-third of the population directly or through informants, producing social paranoia, family betrayals, and the collapse of civic bonds that persisted long after the surveillance state ended.

The poisonous threshold is not merely metaphorical. Excessive surveillance produces tangible toxicity: it enables targeting of political opponents, journalists, and activists. It facilitates identity theft and fraud when databases are breached. It perpetuates discrimination when algorithmic systems trained on biased data automate prejudice at scale. It creates economic distortions when surveillance capitalism extracts rents from unavoidable digital infrastructure. It generates international instability when states use surveillance tools for transnational repression.

Critically, the transition from distasteful to poisonous is difficult to reverse. Once surveillance infrastructure is built, bureaucratic momentum, commercial interests, and political convenience resist dismantling. Once populations habituate to surveillance as normal, the memory of privacy atrophies. Once democratic norms erode, restoring them requires generational effort. The salt metaphor's warning about excess is therefore not counsel for moderation but a red line: beyond the tiny optimal quantity lies a one-way descent into institutional toxicity.

## Usage and Instances

### Original Formulations

Sunil Abraham articulated the surveillance-as-salt comparison in his 2011 opinion piece ["Privacy and Security Can Co-exist"](/publications/privacy-and-security-can-co-exist/) published in *Mail Today* on 21 June 2011. In this article, he wrote:

> Surveillance in any society is like salt in cooking—essential in small quantities but completely counter-productive even slightly in excess. Blanket surveillance makes privacy extinct, it compromises anonymity, essential ingredients for democratic governance, free media, arts and culture, and, most importantly, commerce and enterprise. The Telegraph Act only allowed for blanket surveillance as the rarest of the rare exception. The IT Act, on the other hand, mandates multitiered blanket surveillance of all law-abiding citizens and enterprises.

The piece critiqued the Information Technology Act's blanket surveillance provisions and cybercafé logging rules, contrasting them with the Telegraph Act's more restrained approach that permitted surveillance only as an exceptional measure.

An early instance appears in a 2012 open letter titled ["Open Letter to Hillary Clinton on Internet Freedom"](/publications/open-letter-to-hillary-clinton-on-internet-freedom/), published in *Thinking Aloud* on 17 July 2012. Based on a presentation delivered at Google's Internet at Liberty 2012 conference in Washington DC, Sunil framed surveillance as essential but dangerous when excessive. He wrote: "Surveillance is like salt in cooking—essential in very small quantities but dangerous even if slightly in excess. Blanket surveillance technologies are only going make things easier for—and will only serve as targets for—current and future online villains". This set the tone for his advocacy at the Centre for Internet and Society, which he co-founded.

In 2013, at the CyFy conference organised by the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi on 14–15 October 2013, Sunil reiterated the salt analogy during a panel discussion on privacy and national security. The conference report noted his intervention: "Targeted surveillance has proven effective, but too much surveillance is demonstrably counter-productive". Sunil stressed the need for precision in monitoring to avoid counterproductive outcomes, drawing from discussions on cyber threats and civil liberties.

The comparison appeared again in a 2014 profile published in *The Hindu* on 2 September 2014. In the article ["Fighting Battles Online"](/media/fighting-battles-online-the-hindu/), Sunil stated: "Surveillance is like adding salt in cooking. It is essential in small quantities, but counter productive even if it is slightly in excess". He expanded on this principle by noting that whilst surveillance may be a good idea to keep public servants occupying high office under scrutiny, employing mass surveillance on everybody may not work well. He articulated a framework where privacy is inversely proportional to the power a person wields, whilst transparency is directly proportional to the power a person wields.

Sunil employed the metaphor prominently in his 2016 essay ["Surveillance Project"](/publications/surveillance-project/), published as a chapter in *Dissent on Aadhaar: Big Data Meets Big Brother* edited by Reetika Khera. The chapter described the Aadhaar programme as a mass surveillance system masquerading as development infrastructure. He wrote: "This time for surveillance, which I believe should be used like salt in cooking. Essential in small quantities but counterproductive even if slightly in excess". He clarified that he was not opposed to surveillance as such but rather to its inappropriate deployment for routine citizen-state interactions.

In 2017, Sunil used the analogy during media commentary on the Central Monitoring System, a government surveillance infrastructure. Speaking to *The Hindu* in the article ["Checks and Balances Needed for Mass Surveillance of Citizens, Say Experts"](/media/checks-balances-mass-surveillance-experts-hindu/), he stated: "Surveillance is like salt in cooking which is essential in tiny quantities, but counterproductive even if slightly in excess". He advocated for privacy-by-design principles and proposed tokenisation mechanisms to limit exposure of Aadhaar numbers during know-your-customer processes.

In a 2018 opinion piece titled ["It's the Technology, Stupid"](/publications/its-the-technology-stupid/) published in *The Hindu BusinessLine* on 10 March 2018, Sunil employed the salt analogy to critique Aadhaar's reliance on biometric technology. He wrote: "Biometrics is surveillance technology, a necessity for any State. However, surveillance is much like salt in cooking: essential in tiny quantities, but counterproductive even if slightly in excess". The article argued that biometrics should be used for targeted surveillance rather than routine e-governance, outlining eleven structural flaws that make biometric systems unsuitable for citizen authentication.

He revisited the comparison in another *The Hindu* article titled ["Targeting Surveillance"](/media/targeting-surveillance-hindu/) where he cautioned against India replicating Western mistakes with big data surveillance. He observed: "Surveillance is like salt. It could be counter-productive even if slightly in excess. Ideally, surveillance must be targeted. Indiscriminate surveillance just increases the size of the haystack, making it difficult to find the needles".

### Scholarly Citations

The metaphor has been referenced by other scholars and commentators analysing Indian surveillance systems. In a 2021 op-ed titled ["Pegasus Is India's Watergate Moment"](/media/pegasus-indias-watergate-moment-hindu/) published in *The Hindu* on 21 July 2021, internet researcher Pranesh Prakash invoked this analogy. Writing in the context of the Pegasus spyware revelations, he noted:

> My former colleague, Sunil Abraham, often likens surveillance to salt. A small amount of surveillance is necessary for the health of the body politic, just as salt is for the body; in excess, both are dangerous.

Pranesh used the comparison to argue that whilst liberties depend on national security, national security becomes meaningless if it undermines the very liberties it is supposed to protect.

The comparison has also appeared in activist writing and academic citations. A 2021 [LinkedIn article](https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mass-surveillance-system-aadhar-awakening-aman-sagar) by Aman Sagar quoted Sunil's formulation in the context of analysing Aadhaar as a mass surveillance system. These secondary invocations demonstrate how the analogy has entered wider discourse on digital rights, surveillance reform, and accountability in India.

### Social Media Usage

Sunil has repeatedly employed the salt metaphor in social media discussions, particularly on X (formerly Twitter), where it has become a shorthand for his position on proportionate surveillance. These posts span from 2011 to 2023, demonstrating the metaphor's enduring relevance in his public commentary.

One of the earliest documented uses appears in a 30 September 2011 post during discussions around the Internet Governance Forum: "Surveillance is like salt in food. Essential in small amounts and dangerous even if slightly in excess". This formulation predates many of his published essays, suggesting the comparison emerged organically in informal digital rights discourse before being refined in formal publications.

In February 2012, Sunil corrected a media misquote, clarifying his precise formulation: "The article misquotes me - I said 'surveillance is like salt in cooking, a tiny bit is essential but very dangerous in excess'". This attention to exact wording suggests the metaphor had already become a signature element of his advocacy.

Throughout 2014, as India's Aadhaar programme expanded, Sunil used the metaphor repeatedly in exchanges with policymakers and digital rights advocates. In May 2014, responding to questions about surveillance policy, he stated: "Surveillance is like salt in cooking, essential in small amounts but counterproductive in excess". The following September, he elaborated: "Surveillance is like salt in cooking. Essential in tiny amounts but counterproductive even if slightly in excess".

By 2016 and 2017, as debates over Aadhaar intensified, the metaphor appeared more frequently in Sunil's public commentary. In November 2016, discussing U.S. surveillance practices with digital rights lawyer Pranesh Prakash, he remarked: "As I have said before - surveillance is like salt in cooking!" In February 2017, during heated exchanges about Aadhaar's privacy implications, he posted: "Gastronomically speaking surveillance is like salt in cooking!"

In October 2023, Sunil expanded on the metaphor's theoretical underpinnings, describing it as "the inverted hockey line on a graph with security on x-axis and % of pop under surveillance on y-axis". This visualisation adds a quantitative dimension to the culinary analogy, suggesting that surveillance effectiveness peaks at low levels of population coverage and declines as monitoring becomes more universal.

The metaphor has been widely amplified by other commentators and organisations. In December 2017, Carnegie India documented Sunil's use of the comparison at a panel moderated by Justice B.N. Srikrishna: "Surveillance is like salt in cooking. It is essential in tiny quantities but counterproductive even if slightly in excess. We need to take Ann Cavoukian's advice and design a surveillance system that has privacy by design built into it". The Observer Research Foundation similarly quoted the formulation during its CyFy 2015 conference: "Optimal surveillance is like salt in cooking—necessary in small quantities, bad in excess".

## Internet Governance Perspective

From an internet governance perspective, the surveillance-as-salt principle engages fundamental questions about the design of digital infrastructure and the power dynamics embedded in technological systems. Sunil's work at the Centre for Internet and Society has consistently emphasised that technological architectures are not neutral but rather encode particular values and power relationships.

The salt metaphor aligns with the principle of data minimisation central to privacy-protective regulatory frameworks such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Data minimisation holds that systems should collect only the minimum data necessary for a specified purpose, rather than accumulating vast datasets on the assumption they might prove useful. Sunil's framework extends this principle to surveillance infrastructure, arguing that security systems should be designed from the outset with restraint and proportionality rather than maximal data capture.

This perspective challenges the dominant paradigm in contemporary internet governance wherein both governments and technology platforms operate on an assumption of data abundance. Platforms such as Facebook collect extensive behavioural data (including how long users hesitate over images, which video segments they rewatch, and granular patterns of engagement) not because such data is necessary for service provision but because it enhances advertising targeting. Sunil argues that this model creates catastrophic security vulnerabilities, as demonstrated by the Cambridge Analytica breach where a legitimate API became a vector for mass data exfiltration.

In the Indian internet governance context, the salt metaphor critiques the state's approach to intermediary regulation and surveillance mandates. The 2011 Intermediaries Guidelines and subsequent amendments expanded obligations on digital platforms to retain user data, remove content within 36 hours of complaint, and cooperate with law enforcement. These requirements, Sunil contends, transform intermediaries into instruments of state surveillance and private censorship, undermining constitutional protections for free expression.

The framework also speaks to questions of digital sovereignty and the geopolitics of surveillance. Sunil has examined how surveillance technologies and architectures developed in Western contexts (often in response to terrorism or national security imperatives) become exported to the Global South where they interact with different political economies and democratic traditions. He warns against India adopting mass surveillance models that have proven counterproductive elsewhere, arguing instead for regulatory approaches tailored to India's constitutional commitments and development priorities.

The surveillance-as-salt principle has particular resonance when examining Aadhaar's reversal of transparency logic. As Sunil notes in his ["Surveillance Project"](/publications/surveillance-project/) chapter, traditional internet architecture distributes power and makes central authorities more visible. Aadhaar inverts this relationship by creating total visibility of citizens to the state whilst rendering state surveillance opaque and unaccountable. This architectural flaw cannot be corrected through procedural or legal patches because the centralised design itself embodies excessive surveillance.

## Regulatory Implications

The surveillance-as-salt principle carries significant implications for the design of regulatory frameworks governing digital systems, data protection, and national security. Sunil's formulation challenges policymakers to move beyond binary choices between unfettered surveillance and complete prohibition, arguing instead for governance mechanisms that enable proportionate, targeted, and accountable surveillance practices.

A core regulatory implication concerns the legal standards for authorising surveillance. The framework suggests that surveillance should be subject to strict necessity and proportionality tests, authorised only where there is reasonable suspicion of specific unlawful activity rather than as a blanket precaution. The Indian Telegraph Act historically embodied this approach by permitting interception only in exceptional circumstances. The Information Technology Act, by contrast, mandates multi-tiered surveillance of all citizens and enterprises as a default condition.

The metaphor also informs debates on data retention mandates imposed on intermediaries. Requiring platforms and service providers to retain user data indefinitely or for prolonged periods creates "toxic assets" that pose ongoing security risks whilst enabling state surveillance at scale. A surveillance-as-salt approach would favour short retention periods aligned to specific investigative needs rather than indefinite warehousing of personal data.

Privacy-by-design emerges as a regulatory principle directly derived from the salt framework. Rather than retrofitting privacy protections onto surveillance-intensive systems, Sunil advocates for building technical architectures that structurally limit data collection and access. His proposal for Aadhaar tokenisation exemplifies this approach. Citizens could authenticate their identity without revealing their actual Aadhaar number to service providers, thereby reducing surveillance capacity whilst maintaining functionality.

During a 2017 panel discussion moderated by Justice B.N. Srikrishna at Carnegie India's Global Technology Summit, Sunil explained the tokenisation proposal in detail. He noted that whenever there is a know-your-customer requirement, the Aadhaar number would not be accessed by organisations like telecom firms or banks. Instead, when citizens use various services via smart cards or PINs, a token gets generated, which is controlled by UIDAI. Organisations like banks and telecom firms can store those token numbers in their database. This approach would make it harder for unauthorised parties to combine databases whilst still enabling law enforcement agencies to combine databases using appropriate authorisations and infrastructure.

The principle also speaks to the governance of artificial intelligence and algorithmic systems. Sunil's work on [AI regulation](/publications/artificial-intelligence-full-spectrum-regulatory-challenge/) emphasises that different applications of AI pose vastly different risks depending on context, user, and potential harms. A surveillance-as-salt perspective would support granular, context-specific regulation of AI surveillance systems. It would permit targeted use for genuine security purposes whilst restricting mass deployment for social control or citizen scoring.

The need for independent judicial oversight represents another regulatory dimension of the salt framework. During the Carnegie India discussion, lawyer Rahul Matthan emphasised that surveillance currently operates at the mercy of "incestuous State machinery" without external checks. He proposed a mechanism similar to the United States' Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA court), where an independent authority outside the influence of executive agencies must approve mass surveillance requests. This institutional safeguard would operationalise the principle that surveillance should be exceptional and targeted rather than routine and blanket.

Sunil's framework also addresses the inverse surveillance problem, wherein surveillance disproportionately targets marginalised populations whilst failing to scrutinise powerful actors. As he argues in ["Surveillance Project"](/publications/surveillance-project/), effective accountability requires directing surveillance upward at centres of power rather than downward at vulnerable communities. Regulatory frameworks should therefore prioritise transparency requirements for government procurement, corporate lobbying, and political financing over intrusive monitoring of welfare recipients or internet users.

The biometric irreversibility problem poses particular regulatory challenges within a surveillance-as-salt framework. Unlike passwords or PINs that can be changed if compromised, fingerprints and iris scans are permanent biological identifiers. Once biometric data is stolen or leaked, individuals face irreversible privacy violations. Sunil argues that this characteristic makes biometric databases categorically different from conventional identity systems, requiring either prohibition or extraordinarily stringent security and access controls that current regulatory frameworks do not provide.

## See also

- [Repeat after me (Tweet Series)](/sunil/repeat-after-me/) — Sunil Abraham's 2017 Twitter thread critiquing Aadhaar as surveillance technology