---

title: "Contingency Tables (ELMR Chapter 6)"

author: "Dr. Hua Zhou @ UCLA"

date: "Apr 21, 2020"

output:

# ioslides_presentation: default

html_document:

toc: true

toc_depth: 4

subtitle: Biostat 200C

---

```{r setup, include=FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(fig.align = 'center', cache = FALSE)

```

Display system information and load `tidyverse` and `faraway` packages

```{r}

sessionInfo()

library(tidyverse)

library(faraway)

```

`faraway` package contains the datasets in the ELMR book.

## Two-by-two tables

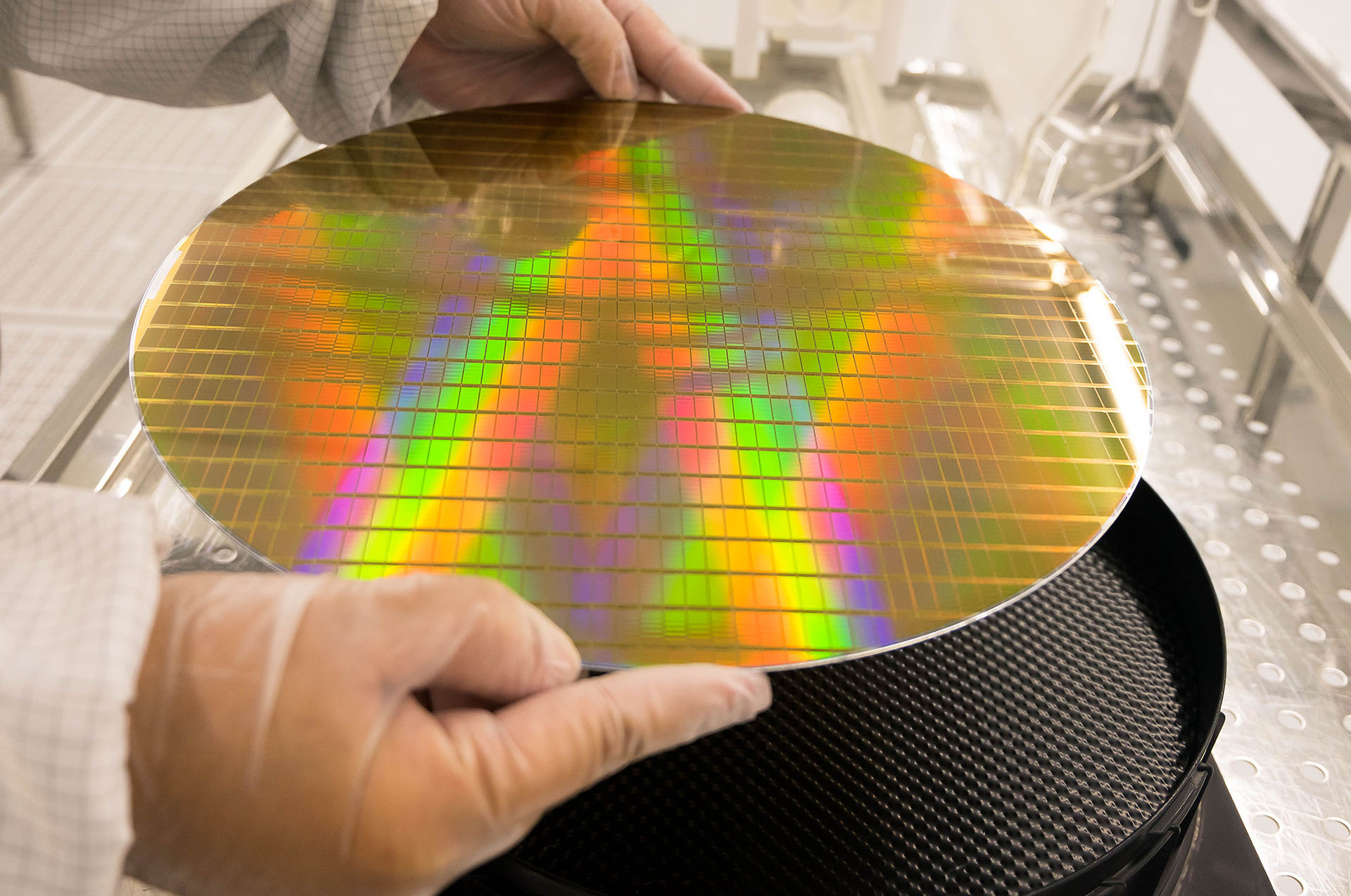

Image source:

- Semiconductor wafer quality data. The research question is whether the presence of particles on the die affects the quality of the wafer being produced.

```{r}

(wafer <- tibble(

y = c(320, 14, 80, 36),

particle = gl(2, 1, length = 4, labels = c("no", "yes")),

quality = gl(2, 2, labels = c("good", "bad"))))

```

This kind of data is conveniently presented as a $2 \times 2$ contingency table.

```{r}

(ytable <- xtabs(y ~ particle + quality, data = wafer))

```

- The usual Pearson $X^2$ test compares the test statistic

$$

X^2 = \sum_{i, j} \frac{(y_{ij} - \widehat \mu_{ij})^2}{\widehat \mu_{ij}},

$$

where

$$

\widehat \mu_{ij} = n \widehat p_i \widehat p_j = n \frac{\sum_j y_{ij}}{n} \frac{\sum_i y_{ij}}{n},

$$

to $\chi_1^2$.

```{r}

summary(ytable)

```

- We will analyze this data using 4 different models according to 4 different sampling schemes. They all reach the same conclusion.

### Poisson model

- We observe the manufacturing process for a certain period of time and observe 450 wafers. The data are then cross-classified. We model the observed counts by Poisson.

```{r}

library(gtsummary)

glm(y ~ particle + quality, family = poisson, data = wafer) %>%

#tbl_regression()

summary()

```

- The null (intercept-only model) model assumes that the rate is constant across particle and quality levels. The analysis of deviance compares $474.10 - 54.03$ to 2 degrees of freedom, indicating null model is rejected in favor of our two predictor Poisson model.

- If we add an interaction term `particle * quality`, the model costs 4 parameters, the same number as the observations. It is equivalent to the full/saturated model. Analysis of deviance compares `54.03` on 1 degree of freedom, indicating the interaction term is highly significant.

- Therefore our conclusion is that presence of particle in the die significantly affects the quality of wafer.

### Multinomial model

- If we assume the total sample size is fixed at $n=450$. Then we can model the counts by a multinomial model. We consdier two models

- $H_1$: one full/saturated model where each cell of the $2 \times 2$ has its own probability $p_{ij}$, and

- $H_0$: one reduced model that assumes `particle` is independent of `quality`, thus $p_{ij} = p_i p_j$.

- For the full/saturated model $H_1$, the multinomial likelihood is

$$

\frac{n!}{\prod_i \prod_j y_{ij}!} \prod_i \prod_j p_{ij}^{y_{ij}}.

$$

We estimate $p_{ij}$ by the cell proportion (MLE)

$$

\widehat{p}_{ij} = \frac{y_{ij}}{n}.

$$

- For the reduced model assuming independence $H_0$, the multinomial likelihood is

$$

\frac{n!}{\prod_i \prod_j y_{ij}!} \prod_i \prod_j (p_i p_j)^{y_{ij}} = \frac{n!}{\prod_i \prod_j y_{ij}!} p_i^{\sum_j y_{ij}} p_j^{\sum_i y_{ij}}.

$$

The MLE is

$$

\widehat{p}_i = \frac{\sum_j y_{ij}}{n}, \quad \widehat{p}_j = \frac{\sum_i y_{ij}}{n}.

$$

- The analysis deviance compares the deviance

\begin{eqnarray*}

D &=& 2 \sum_i \sum_j y_{ij} \log \frac{y_{ij}}{n} - 2 \sum_i \left(\sum_j y_{ij}\right) \log \widehat{p}_i - 2 \sum_j \left(\sum_i y_{ij}\right) \log \widehat{p}_j \\

&=& 2 \sum_i \sum_j y_{ij} \log \frac{y_{ij}}{n \widehat{p}_i \widehat{p}_j} \\

&=& 2 \sum_i \sum_j y_{ij} \log \frac{y_{ij}}{\widehat{\mu}_{ij}}

\end{eqnarray*}

to 1 degree of freedom.

```{r}

(partp <- xtabs(y ~ particle, data = wafer) %>% prop.table())

(qualp <- xtabs(y ~ quality, data = wafer) %>% prop.table())

muhat <- 450 * outer(partp, qualp)

ytable <- xtabs(y ~ particle + quality, data = wafer)

2 * sum(ytable * log(ytable / muhat))

```

- We get the exact same result as the analysis of deviance in the Poisson model.

- This connection between Poisson and multinomial is no surprise due to the following fact. If $Y_1, \ldots, Y_k$ are independent Poisson with means $\lambda_1, \ldots, \lambda_k$, then the joint distribution of $Y_1, \ldots, Y_k \mid \sum_i Y_i = n$ is multinomial with probabilities $p_j = \lambda_j / \sum_i \lambda_i$.

### Binomial

- If we view `particle` as a predictor affecting whether a wafer is good quality or bad quality, we end up with an independent binomial model.

- The null (intercept-only) model corresponds to the hypothesis `particle` does not affect quality.

```{r}

tibble(good = c(320, 14),

bad = c(80, 36),

particle = c("no", "yes")) %>%

print() %>%

glm(cbind(good, bad) ~ 1, family = binomial, data = .) %>%

summary()

```

The alternative model corresponds to the full/saturated model where `particle` is included as a predictor.

- Again we observe the exactly same analysis of deviance inference.

- When there are more than two rows or columns, this model is called the **product binoimal/multinomial model**.

### Hypergeometric

- Finally if we fix both row and column marginal totals, the probability of the observed table is

\begin{eqnarray*}

p(y_{11}, y_{12}, y_{21}, y_{22}) &=& \frac{\binom{y_{1\cdot}}{y_{11}} \binom{y_{2\cdot}}{y_{22}} \binom{y_{\cdot 1}}{y_{21}} \binom{y_{\cdot 2}}{y_{12}}}{\binom{n}{y_{11} \, y_{12} \, y_{21} \, y_{22}}} \\

&=& \frac{y_{1\cdot}! y_{2\cdot}! y_{\cdot 1}! y_{\cdot 2}!}{y_{11}! y_{12}! y_{21}! y_{22}! n!} \\

&=& \frac{\binom{y_{1 \cdot}}{y_{11}} \binom{y_{2 \cdot}}{y_{\cdot 1} - y_{11}}}{\binom{n}{y_{\cdot 1}}}.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Under the null hypothesis that `particle` is not associated with `quality`, the **Fisher's exact test** calculates the p-value by summing over the probabilities of tables with more extreme observations

$$

\sum_{y_{11} \ge 320} p(y_{11}, y_{12}, y_{21}, y_{22}).

$$

```{r}

fisher.test(ytable)

```

The odds ratio is

$$

\frac{\pi_{\text{no particle}} / (1 - \pi_{\text{no particle}})}{\pi_{\text{particle}} / (1 - \pi_{\text{particle}})} = \frac{y_{11} y_{22}}{y_{12} y_{21}}

$$

```{r}

(320 * 36) / (14 * 80)

```

## Larger two-way tables

- The `haireye` data set contains data on 592 statistics students cross-classifed by hair and eye color.

```{r}

haireye <- as_tibble(haireye) %>%

print(n = Inf)

(haireye_table <- xtabs(y ~ hair + eye, data = haireye))

```

- Graphical summary of the contingency table by a **mosaic plot**. If `eye` and `hair` are independent, we expect to see a grid.

```{r}

mosaicplot(haireye_table, color = TRUE, main = NULL, las = 1)

```

- Pearson $X^2$ test for independence yields

```{r}

summary(haireye_table)

```

- We fit a Poisson GLM:

```{r}

modc <- glm(y ~ hair + eye, family = poisson, data = haireye)

summary(modc)

```

which clearly shows a lack of fit. The interaction model is equivalent to the full/saturated model. Therefore we see strong evidence for the dependence between `eye` and `hair`.

- We follow up by a **correspondence analysis** to study how `eye` and `hair` are dependent.

1. We first compute the matrix of Pearson residuals $\mathbf{R}$.

```{r}

(R <- xtabs(residuals(modc, type = "pearson") ~ hair + eye, data = haireye))

```

2. Let the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the Pearson residual matrix be $\mathbf{R} = \mathbf{U} \boldsymbol{\Sigma} \mathbf{V}^T$. Then the best rank-2 approximation to the residual matrix is

\begin{eqnarray*}

\mathbf{R} &\approx& \sigma_1 \mathbf{u}_1 \mathbf{v}_1^T + \sigma_2 \mathbf{u}_2 \mathbf{v}_2^T \\

&=& (\sqrt{\sigma_1} \mathbf{u}_1) (\sqrt{\sigma_1} \mathbf{v}_1)^T + (\sqrt{\sigma_2} \mathbf{u}_2)(\sqrt{\sigma_2} \mathbf{v}_2)^T \\

&=& \tilde{\mathbf{u}}_1 \tilde{\mathbf{v}}_1^T + \tilde{\mathbf{u}}_2 \tilde{\mathbf{v}}_2^T,

\end{eqnarray*}

where $(\sigma_i, \mathbf{u}_i, \mathbf{v}_i)$, $i=1,2$, are the top singular values and vectors. For refresher of SVD, read Biostat 216 [slides](https://ucla-biostat216-2019fall.github.io/slides/12-svd/12-svd.html).

```{r}

(svdr <- svd(R, nu = 2, nv = 2))

```

3. Finally we plot $\tilde{\mathbf{u}}_2$ against $\tilde{\mathbf{u}}_1$ and $\tilde{\mathbf{v}}_2$ against $\tilde{\mathbf{v}}_1$ on a **correspondence analysis plot**.

```{r}

cplot_df <- tibble(

dim1 = sqrt(svdr$d[1]) * c(svdr$u[, 1], svdr$v[, 1]),

dim2 = sqrt(svdr$d[2]) * c(svdr$u[, 2], svdr$v[, 2]),

label = c(rownames(R), colnames(R)),

var = rep(c("hair", "eye"), each = 4)) %>%

print(n = Inf)

```

```{r}

library(ggrepel)

# percent of variance explained

pve1 <- svdr$d[1] / sum(svdr$d)

pve2 <- svdr$d[2] / sum(svdr$d)

cplot_df %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(x = dim1, y = dim2, color = var, shape = var)) +

geom_point() +

geom_label_repel(mapping = aes(label = label), show.legend = F) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, lty = "dashed", alpha = 0.5) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, lty = "dashed", alpha = 0.5) +

labs(x = str_c("Dimension 1 (", signif(pve1 * 100, 3), "%)"),

y = str_c("Dimension 2 (", signif(pve2 * 100, 3), "%)"))

```

4. To read the correspondence analysis plot:

- Perason's $X^2 = \sum_{i,j} r_{ij}^2 = \sum_k \sigma_k^2$ is called the _inertia_.

- Large values of $|\tilde{u}_i|$ or $|\tilde{v}_i|$ indicates that level is a typical. For example, `BLONDE` hair.

- If row and column levels appear close together and far from the origin, then there is a strong positive association. For example, `BLONDE` hair + `blue` eye. If they are diametrically apart on either side of the origin, then there is a strong negative association. For example, `BLONDE` hair + `brown` eye.

- If two row levels or column levels are close together, it indicates that the two levels have similar pattern of association,. In some cases, one might consider combining the two levels. For example, `hazel` and `green` eyes.

## Three-way contingency tables

- The `femsoke` data records female smokers and non-smokers, their age group, and whether the subjects were dead or still alive after 20 years.

```{r}

femsmoke <- as_tibble(femsmoke) %>%

print(n = Inf)

```

There are three factors `smoker`, `dead`, and `age`. If we just classify over `smoker` and `dead`

```{r}

(ct <- xtabs(y ~ smoker + dead, data = femsmoke))

prop.table(ct, 1)

```

we see significantly higher percentage of non-smokers died than smokers.

```{r}

summary(ct)

```

- However `smoke` status is confounded with the `age` group. Smokers are more concentrated in the younger groups and younger people are more likely to live for another 20 years.

```{r}

prop.table(xtabs(y ~ smoker + age, data = femsmoke), 2)

```

- The odds ratios in all age groups are:

```{r}

ct3 <- xtabs(y ~ smoker + dead + age, data = femsmoke)

apply(ct3, 3, function (x) (x[1, 1] * x[2, 2]) / (x[1, 2] * x[2, 1]))

```

- The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) tests independence in $2 \times 2$ tables across $K$ strata. It compares the statistic

$$

\frac{(|\sum_k y_{11k} - \sum_k \mathbb{E}y_{11k}| - 1/2)^2}{\sum_k \operatorname{Var} y_{11k}},

$$

where the expectation and variance are computed under the null hypothesis of independence in each stratum, to asymptotic null distribution $\chi_1^2$ and calculate the p-value by exact test.

```{r}

mantelhaen.test(ct3, exact = TRUE)

```

### Mutual independence model

- Under mutual independence,

$$

p_{ijk} = p_i p_j p_k

$$

so

$$

\mathbb{E} Y_{ijk} = n p_{ijk}

$$

and

$$

\log \mathbb{E} Y_{ijk} = \log n + \log p_i + \log p_j + \log p_k.

$$

So the main effect-only model corresponds to the mutual independence model.

- We can test independence by the Pearson $X^2$ test

```{r}

summary(ct3)

```

or by a Poisson GLM

```{r}

modi <- glm(y ~ smoker + dead + age, family = poisson, data = femsmoke)

summary(modi)

```

Both suggest a lack of fit.

```{r}

modi %>% tbl_regression(exponentiate = TRUE, intercept = TRUE)

```

The exponentiated coefficients are just marginal proportions

```{r}

c(1, 1.26) / (1 + 1.26)

prop.table(xtabs(y ~ smoker, femsmoke))

```

### Joint independence

- If we assume the first two variables are dependent, and jointly independent of the third. Then

$$

p_{ijk} = p_{ij} p_k

$$

and

$$

\log \mathbb{E} Y_{ijk} = \log n + \log p_{ij} + \log p_k.

$$

- It leads to a log-linear model with just one interaction

```{r}

glm(y ~ smoker * dead + age, family = poisson, data = femsmoke) %>%

summary()

```

It improves the fit, but still not enough.

### Conditional independence

- Let $P_{ij \mid k}$ be the probability that an observation falls in $(i, j)$-cell given that we know the third variables takes value $k$. If we assume that first two variables are independent give value of the third. Then

$$

p_{ijk} = p_{ij\mid k} p_k = p_{i\mid k} p_{j \mid k} p_k = \frac{p_{ik} p_{jk}}{p_k}.

$$

and

$$

\log \mathbb{E} Y_{ijk} = \log n + \log p_{ik} + \log p_{jk} - \log p_k.

$$

- It leads to a model with two interaction terms

```{r}

glm(y ~ smoker * age + dead * age, family = poisson, data = femsmoke) %>%

summary()

```

This model fits data pretty well.

- Significance of predictors

```{r}

glm(y ~ smoker * age + dead * age, family = poisson, data = femsmoke) %>%

drop1(test = "Chi")

```

### Uniform association

- If we conisder a model with all two-way interactions

$$

\log \mathbb{E}Y_{ijk} = \log n + \log p_i + \log p_j + \log p_k + \log p_{ij} + \log p_{ik} + \log p_{jk}.

$$

- There is no simple interpretation in terms of independence.

```{r}

modu <- glm(y ~ (smoker + age + dead)^2, family = poisson, data = femsmoke)

summary(modu)

```

- If we compute the odds ratio for each age group

```{r}

xtabs(fitted(modu) ~ smoker + dead + age, data = femsmoke) %>%

apply(3, function(x) (x[1, 1] * x[2, 2]) / (x[1, 2] * x[2, 1]))

```

Thus the name uniform association model.

- The odds ratio can also be extracted from the coefficients

```{r}

exp(coef(modu)['smokerno:deadno'])

```

### Model selection

- We can start from the saturated model (3-way interaction) and use the analysis of deviance to see how much we can reduce the model.

```{r}

glm(y ~ smoker * age * dead, family = poisson, data = femsmoke) %>%

step(test = "Chi") %>%

drop1(test = "Chi")

```

The interaction term `smoker:dead` is weakly significant in the final model. This corresponds to the test of conditional independence between `smoke` and `dead` given `age` group. The p-value is very similar to that from the CMH test.

### Binomial

- It also makes intuitive sense to model life status as the outcome depending on perdictors `smoker` and `age`.

```{r}

# glm(dead ~ smoker * age, family = binomial, weights = y, data = femsmoke) %>%

# summary()

glm(matrix(femsmoke$y, ncol = 2) ~ smoker * age, family = binomial, femsmoke[1:14, ]) %>%

step(test = "Chi") %>%

summary()

```

- The final model retains only main effects. This is equivalent to the uniform association model. The deviance is exactly the same.

![]()