---

title: Orthogonal Projections

subtitle: Biostat 216

author: Dr. Hua Zhou @ UCLA

date: today

format:

html:

theme: cosmo

embed-resources: true

number-sections: true

toc: true

toc-depth: 4

toc-location: left

code-fold: false

jupyter:

jupytext:

formats: 'ipynb,qmd'

text_representation:

extension: .qmd

format_name: quarto

format_version: '1.0'

jupytext_version: 1.15.2

kernelspec:

display_name: Julia 1.9.3

language: julia

name: julia-1.9

---

**Highlights** In this lecture, we'll show (1) the **fundamental theorem of linear algebra**:

and (2) any symmetric, idempotent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector onto $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ (along $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}')$).

## Direct sum

- The **sum of two vector spaces** $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ of same order is

$$

\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2: \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2\}.

$$

In HW3, we show that $\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ is a vector space.

- **Dimension of a sum of subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2) - \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2).

$$

Proof (optional): Idea: extend a basis of $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ to ones for $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$. See, e.g., BR p156-157.

- Corollaries.

1. **Subadditivity of dim function.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) \le \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2).

$$

This is an immediate corollary of the preceding theorem. In HW3, we give a self-contained proof without using the preceding theorem.

2. **Subadditivity of rank function.** Let $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ be two matrices of the same order. Then

$$

\text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \le \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}).

$$

Proof: First claim trivially follows from the previous result or your own proof in HW3. For the second claim. First note $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})$ (why?). Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \\

&=& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(definition of rank)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(monotonicity of dim)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(subadditivity of dim)} \\

&=& \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}). \quad \text{(definition of rank)}

\end{eqnarray*}

The second inequality follows from the first claim.

- Two subspaces $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ in a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ are said to be **complementary** whenever

$$

\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 \text{ and } \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}.

$$

In such cases, we say $\mathcal{V}$ is a **direct sum** of $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and denote $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

- TODO: visualize. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{a line}$. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{space of symmetric vectors} \oplus \text{space of anti-symmetric vectors}$ (midterm).

- Let $\mathcal{S}_1, \mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces of same order and $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$. Following statements are equivalent:

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

2. $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

3. Any vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be **uniquely** represented as

$$

\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2, \text{ where } \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathbf{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathbf{S}_2.

$$

We will refer to this as the **unique representation** or **unique decomposition** property of direct sums.

Proof (optional): We show that $1 \Rightarrow 2 \Rightarrow 3 \Rightarrow 1$.

$1 \Rightarrow 2$: By definition of direct sum, we know $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Thus $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

$2 \Rightarrow 3$: By 2, we know $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2) = 0$ so $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ and assume $\mathbf{x}$ can be decomposed in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2$, where $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2$. Then $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1 = -(\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2)$, indicating that the vectors $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2$ belong to both $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and thus must be $\mathbf{0}$. Therefore $\mathbf{u}_1 = \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_2$.

$3 \Rightarrow 1$: We only need to show $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$. Decompose $\mathbf{x}$ in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0} + \mathbf{x}$. Then by the uniqueness part of 3, $\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}$. So the only possible element in $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is $\mathbf{0}$.

and (2) any symmetric, idempotent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector onto $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ (along $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}')$).

## Direct sum

- The **sum of two vector spaces** $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ of same order is

$$

\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2: \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2\}.

$$

In HW3, we show that $\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ is a vector space.

- **Dimension of a sum of subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2) - \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2).

$$

Proof (optional): Idea: extend a basis of $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ to ones for $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$. See, e.g., BR p156-157.

- Corollaries.

1. **Subadditivity of dim function.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) \le \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2).

$$

This is an immediate corollary of the preceding theorem. In HW3, we give a self-contained proof without using the preceding theorem.

2. **Subadditivity of rank function.** Let $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ be two matrices of the same order. Then

$$

\text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \le \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}).

$$

Proof: First claim trivially follows from the previous result or your own proof in HW3. For the second claim. First note $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})$ (why?). Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \\

&=& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(definition of rank)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(monotonicity of dim)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(subadditivity of dim)} \\

&=& \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}). \quad \text{(definition of rank)}

\end{eqnarray*}

The second inequality follows from the first claim.

- Two subspaces $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ in a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ are said to be **complementary** whenever

$$

\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 \text{ and } \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}.

$$

In such cases, we say $\mathcal{V}$ is a **direct sum** of $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and denote $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

- TODO: visualize. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{a line}$. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{space of symmetric vectors} \oplus \text{space of anti-symmetric vectors}$ (midterm).

- Let $\mathcal{S}_1, \mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces of same order and $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$. Following statements are equivalent:

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

2. $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

3. Any vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be **uniquely** represented as

$$

\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2, \text{ where } \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathbf{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathbf{S}_2.

$$

We will refer to this as the **unique representation** or **unique decomposition** property of direct sums.

Proof (optional): We show that $1 \Rightarrow 2 \Rightarrow 3 \Rightarrow 1$.

$1 \Rightarrow 2$: By definition of direct sum, we know $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Thus $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

$2 \Rightarrow 3$: By 2, we know $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2) = 0$ so $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ and assume $\mathbf{x}$ can be decomposed in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2$, where $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2$. Then $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1 = -(\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2)$, indicating that the vectors $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2$ belong to both $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and thus must be $\mathbf{0}$. Therefore $\mathbf{u}_1 = \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_2$.

$3 \Rightarrow 1$: We only need to show $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$. Decompose $\mathbf{x}$ in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0} + \mathbf{x}$. Then by the uniqueness part of 3, $\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}$. So the only possible element in $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is $\mathbf{0}$.

- An immediate corollary of the previous result is, for a matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$,

1. $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})$.

## Ortho-complementary subspaces

- An **orthocomplement set** of a set $\mathcal{X}$ (not necessarily a subspace) in a vector space $\mathcal{V} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$ is defined as

$$

\mathcal{X}^\perp = \{ \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{V}: \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{u} \rangle = 0 \text{ for all } \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X}\}.

$$

$\mathcal{X}^\perp$ is always a vector space regardless $\mathcal{X}$ is a vector space or not.

Proof: midterm.

- TODD: visualize $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{plan}^\perp$.

- **Direct sum theorem for orthocomplementary subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ with $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = m$. Then the following statements are true.

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. That is every vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expressed as $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$, where $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

2. $\mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp = \{\mathbf{0}\}$ (essentially disjoint).

3. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

4. $m = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}^\perp)$.

By the uniqueness of decomposition for direct sum, we know the expression of $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ is also **unique**.

Proof of 1: Let $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r\}$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{S}$ and extend it to an orthonormal basis $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r, \mathbf{z}_{r+1}, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_m\}$ of $\mathcal{V}$. Then any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expanded as

$$

\mathbf{y} = (\alpha_1 \mathbf{z}_1 + \cdots + \alpha_r \mathbf{z}_r) + (\alpha_{r+1} \mathbf{z}_{r+1} + \cdots + \alpha_m \mathbf{z}_m),

$$

where the first sum belongs to $\mathcal{S}$ and the second to $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 2: Suppose $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp$, then $\mathbf{x} \perp \mathbf{x}$, i.e., $\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle = 0$. Therefore $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$.

Proof of 3: Statement 1 says $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Statement 2 says $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$ are essentially disjoint. Thus $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 4: Follows from essential disjointness between $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

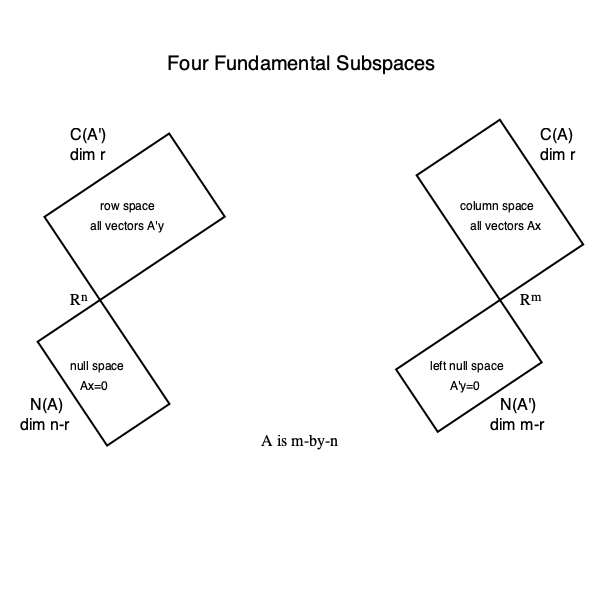

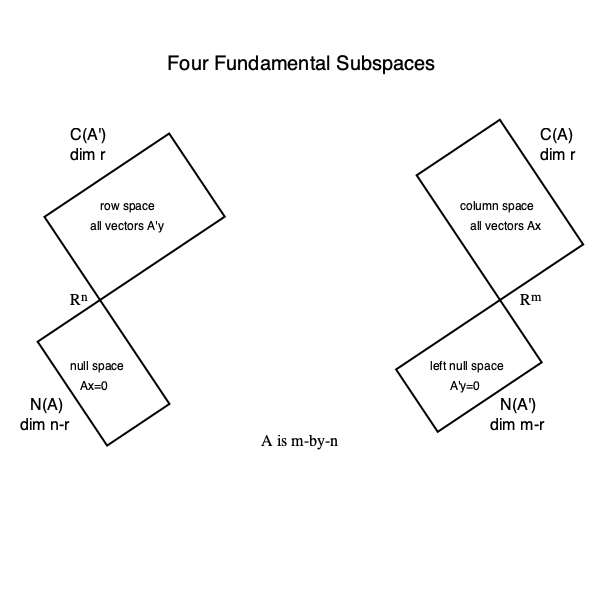

## The fundamental theorem of linear algebra

- Let $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$. Then

1. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

3. $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 1: To show $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \text{ is orthogonal to columns of } \mathbf{A} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp.

\end{eqnarray*}

Then, $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 2: Since $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$ is a subspace, $(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp)^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

Proof of 3: Applying part 2 to $\mathbf{A}'$, we have

$$

\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') = \mathcal{N}((\mathbf{A}')')^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp

$$

and

$$

\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}').

$$

## Orthogonal projections

- An immediate corollary of the previous result is, for a matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$,

1. $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})$.

## Ortho-complementary subspaces

- An **orthocomplement set** of a set $\mathcal{X}$ (not necessarily a subspace) in a vector space $\mathcal{V} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$ is defined as

$$

\mathcal{X}^\perp = \{ \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{V}: \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{u} \rangle = 0 \text{ for all } \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X}\}.

$$

$\mathcal{X}^\perp$ is always a vector space regardless $\mathcal{X}$ is a vector space or not.

Proof: midterm.

- TODD: visualize $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{plan}^\perp$.

- **Direct sum theorem for orthocomplementary subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ with $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = m$. Then the following statements are true.

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. That is every vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expressed as $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$, where $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

2. $\mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp = \{\mathbf{0}\}$ (essentially disjoint).

3. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

4. $m = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}^\perp)$.

By the uniqueness of decomposition for direct sum, we know the expression of $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ is also **unique**.

Proof of 1: Let $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r\}$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{S}$ and extend it to an orthonormal basis $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r, \mathbf{z}_{r+1}, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_m\}$ of $\mathcal{V}$. Then any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expanded as

$$

\mathbf{y} = (\alpha_1 \mathbf{z}_1 + \cdots + \alpha_r \mathbf{z}_r) + (\alpha_{r+1} \mathbf{z}_{r+1} + \cdots + \alpha_m \mathbf{z}_m),

$$

where the first sum belongs to $\mathcal{S}$ and the second to $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 2: Suppose $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp$, then $\mathbf{x} \perp \mathbf{x}$, i.e., $\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle = 0$. Therefore $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$.

Proof of 3: Statement 1 says $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Statement 2 says $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$ are essentially disjoint. Thus $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 4: Follows from essential disjointness between $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## The fundamental theorem of linear algebra

- Let $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$. Then

1. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

3. $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 1: To show $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \text{ is orthogonal to columns of } \mathbf{A} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp.

\end{eqnarray*}

Then, $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 2: Since $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$ is a subspace, $(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp)^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

Proof of 3: Applying part 2 to $\mathbf{A}'$, we have

$$

\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') = \mathcal{N}((\mathbf{A}')')^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp

$$

and

$$

\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}').

$$

## Orthogonal projections

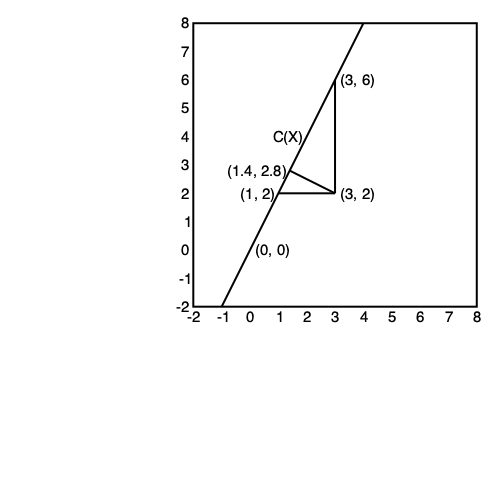

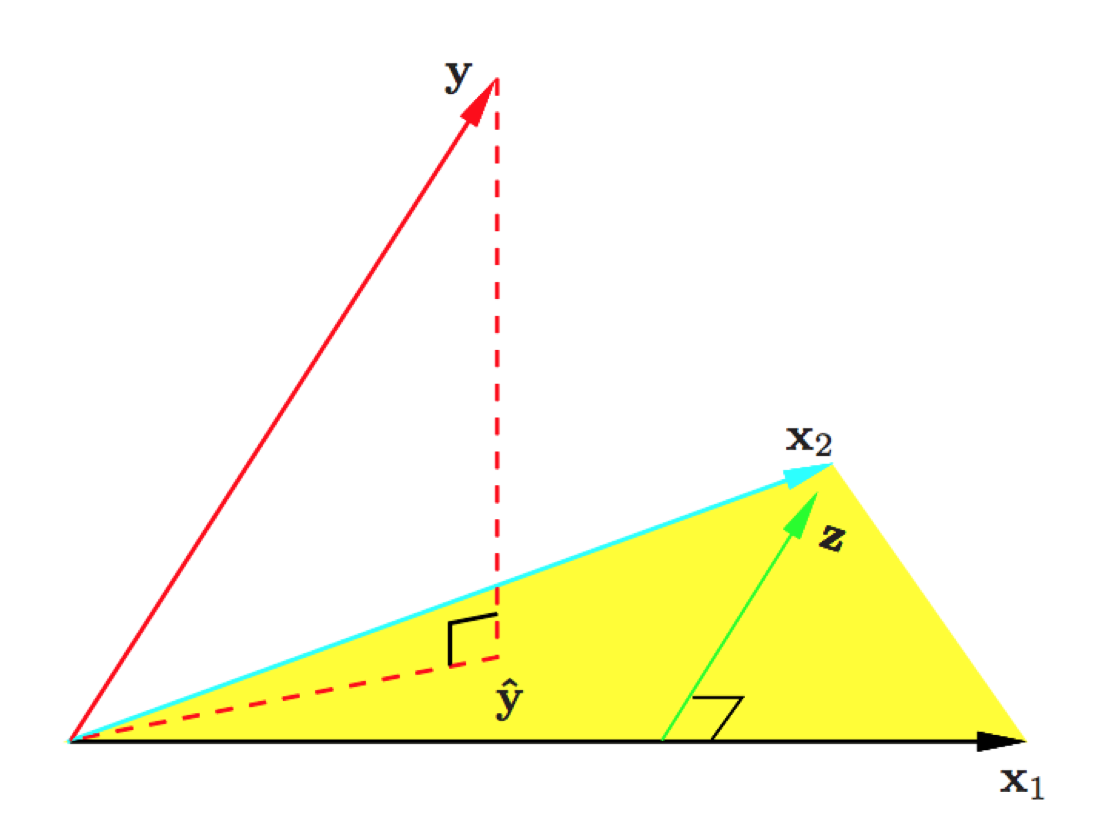

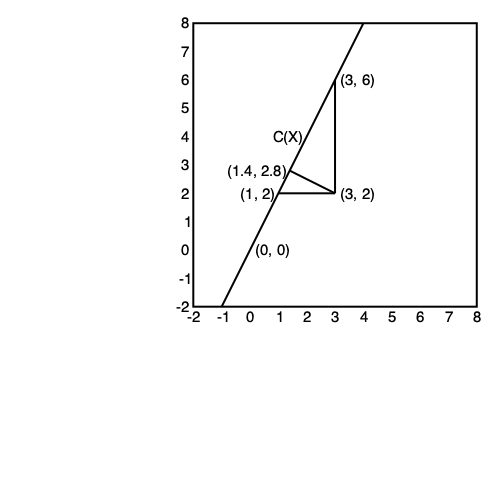

- Suppose $\mathcal{S}$ is a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. Let $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ be the unique representation of $\mathbf{y}$ with $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Then the vector $\mathbf{u}$ is called the **orthogonal projection** of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ (along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$).

- **The closest point theorem.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of some vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. The orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ is the **unique** point in $\mathcal{S}$ that is closest to $\mathbf{y}$. In other words, if $\mathbf{u}$ is the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$, then

$$

\|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 \le \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \text{ for all } \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S},

$$

with equality holding only when $\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{u}$.

Proof: Picture.

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + 2(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u})'(\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}) + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \quad \quad \quad (\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S}, \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp) \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&\ge& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Let $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$. A square matrix $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}}$ is called the **orthogonal porjector** into $\mathcal{S}$ if, for every $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}} \mathbf{y}$ is the projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## Orthogonal projector into a column space

Let $\mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{x}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{x}_p \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$. We construct the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ using different ways.

### Method 1

Let $\mathbf{q}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{q}_r$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, e.g., by Gram-Schmidt with pivoting. Then

$$

\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}', \text{where } \mathbf{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{q}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{q}_r \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix},

$$

is the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we show $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} + (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y})$ such that $\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ and $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{X}')$.

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q}) = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X}).

$$

And

$$

\mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{0}_r

$$

thus $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{Q}') = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$.

### Method 2

- Suppose $\mathcal{S}$ is a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. Let $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ be the unique representation of $\mathbf{y}$ with $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Then the vector $\mathbf{u}$ is called the **orthogonal projection** of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ (along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$).

- **The closest point theorem.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of some vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. The orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ is the **unique** point in $\mathcal{S}$ that is closest to $\mathbf{y}$. In other words, if $\mathbf{u}$ is the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$, then

$$

\|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 \le \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \text{ for all } \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S},

$$

with equality holding only when $\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{u}$.

Proof: Picture.

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + 2(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u})'(\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}) + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \quad \quad \quad (\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S}, \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp) \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&\ge& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Let $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$. A square matrix $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}}$ is called the **orthogonal porjector** into $\mathcal{S}$ if, for every $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}} \mathbf{y}$ is the projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## Orthogonal projector into a column space

Let $\mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{x}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{x}_p \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$. We construct the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ using different ways.

### Method 1

Let $\mathbf{q}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{q}_r$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, e.g., by Gram-Schmidt with pivoting. Then

$$

\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}', \text{where } \mathbf{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{q}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{q}_r \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix},

$$

is the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we show $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} + (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y})$ such that $\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ and $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{X}')$.

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q}) = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X}).

$$

And

$$

\mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{0}_r

$$

thus $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{Q}') = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$.

### Method 2

1. The orthogonal projector of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$, where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ satisfies the **normal equation**

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Normal equation always has solution(s) (why?) and any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^-$ yields a solution $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$. Therefore,

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}'.

$$

for any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^-$.

2. If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, then the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}'.

$$

Proof of 1: Since the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ lives in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, thus can be written as $\mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$ for some $\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^p$. Furthermore, $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$ is orthogonal to any vectors in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ including the columns of $\mathbf{X}$. Thus

$$

\mathbf{X}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) = \mathbf{0},

$$

or equivalently,

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Proof of 2: If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, $\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X}$ is non-singular and the solution to the normal equation is uniquely determined by $\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$, and the orthogonal projection is $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$.

## Uniqueness of orthogonal projector

We have multiple ways to construct an orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$. This leaves the natural question: are orthogonal projectors into the same vector space unique? The answer is a happy yes.

- Theorem: Let $\mathbf{P}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{P}_2$ be two orthogonal projectors into a vector space $\mathcal{S}$. Then $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

Proof: By the uniqueness of the decomposition of direct sums, $\mathbf{P}_1 \mathbf{e}_i$ = $\mathbf{P}_2 \mathbf{e}_i$ for all $i$. Thus $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

## Any symmetric, idempotent matrix is an orthogonal projector

By the construction of orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}'$, we see $\mathbf{P}$ is symmetric and **idempotent**

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{P}.

$$

It turns out the reverse is also true.

- Theorem: Any symmetric, idemponent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, let $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w}$, where $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ and $\mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}') = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P})$. Since $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$, $\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u}$ for some $\mathbf{u} \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Then $\mathbf{P}\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{v}$. Thus $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

1. The orthogonal projector of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$, where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ satisfies the **normal equation**

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Normal equation always has solution(s) (why?) and any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^-$ yields a solution $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$. Therefore,

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}'.

$$

for any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^-$.

2. If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, then the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}'.

$$

Proof of 1: Since the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ lives in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, thus can be written as $\mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$ for some $\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^p$. Furthermore, $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$ is orthogonal to any vectors in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ including the columns of $\mathbf{X}$. Thus

$$

\mathbf{X}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) = \mathbf{0},

$$

or equivalently,

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Proof of 2: If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, $\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X}$ is non-singular and the solution to the normal equation is uniquely determined by $\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$, and the orthogonal projection is $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$.

## Uniqueness of orthogonal projector

We have multiple ways to construct an orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$. This leaves the natural question: are orthogonal projectors into the same vector space unique? The answer is a happy yes.

- Theorem: Let $\mathbf{P}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{P}_2$ be two orthogonal projectors into a vector space $\mathcal{S}$. Then $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

Proof: By the uniqueness of the decomposition of direct sums, $\mathbf{P}_1 \mathbf{e}_i$ = $\mathbf{P}_2 \mathbf{e}_i$ for all $i$. Thus $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

## Any symmetric, idempotent matrix is an orthogonal projector

By the construction of orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}'$, we see $\mathbf{P}$ is symmetric and **idempotent**

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{P}.

$$

It turns out the reverse is also true.

- Theorem: Any symmetric, idemponent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, let $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w}$, where $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ and $\mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}') = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P})$. Since $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$, $\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u}$ for some $\mathbf{u} \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Then $\mathbf{P}\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{v}$. Thus $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

and (2) any symmetric, idempotent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector onto $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ (along $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}')$).

## Direct sum

- The **sum of two vector spaces** $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ of same order is

$$

\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2: \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2\}.

$$

In HW3, we show that $\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ is a vector space.

- **Dimension of a sum of subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2) - \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2).

$$

Proof (optional): Idea: extend a basis of $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ to ones for $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$. See, e.g., BR p156-157.

- Corollaries.

1. **Subadditivity of dim function.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) \le \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2).

$$

This is an immediate corollary of the preceding theorem. In HW3, we give a self-contained proof without using the preceding theorem.

2. **Subadditivity of rank function.** Let $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ be two matrices of the same order. Then

$$

\text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \le \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}).

$$

Proof: First claim trivially follows from the previous result or your own proof in HW3. For the second claim. First note $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})$ (why?). Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \\

&=& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(definition of rank)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(monotonicity of dim)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(subadditivity of dim)} \\

&=& \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}). \quad \text{(definition of rank)}

\end{eqnarray*}

The second inequality follows from the first claim.

- Two subspaces $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ in a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ are said to be **complementary** whenever

$$

\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 \text{ and } \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}.

$$

In such cases, we say $\mathcal{V}$ is a **direct sum** of $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and denote $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

- TODO: visualize. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{a line}$. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{space of symmetric vectors} \oplus \text{space of anti-symmetric vectors}$ (midterm).

- Let $\mathcal{S}_1, \mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces of same order and $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$. Following statements are equivalent:

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

2. $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

3. Any vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be **uniquely** represented as

$$

\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2, \text{ where } \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathbf{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathbf{S}_2.

$$

We will refer to this as the **unique representation** or **unique decomposition** property of direct sums.

Proof (optional): We show that $1 \Rightarrow 2 \Rightarrow 3 \Rightarrow 1$.

$1 \Rightarrow 2$: By definition of direct sum, we know $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Thus $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

$2 \Rightarrow 3$: By 2, we know $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2) = 0$ so $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ and assume $\mathbf{x}$ can be decomposed in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2$, where $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2$. Then $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1 = -(\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2)$, indicating that the vectors $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2$ belong to both $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and thus must be $\mathbf{0}$. Therefore $\mathbf{u}_1 = \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_2$.

$3 \Rightarrow 1$: We only need to show $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$. Decompose $\mathbf{x}$ in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0} + \mathbf{x}$. Then by the uniqueness part of 3, $\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}$. So the only possible element in $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is $\mathbf{0}$.

and (2) any symmetric, idempotent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector onto $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ (along $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}')$).

## Direct sum

- The **sum of two vector spaces** $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ of same order is

$$

\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2: \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2\}.

$$

In HW3, we show that $\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ is a vector space.

- **Dimension of a sum of subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2) - \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2).

$$

Proof (optional): Idea: extend a basis of $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ to ones for $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$. See, e.g., BR p156-157.

- Corollaries.

1. **Subadditivity of dim function.** Let $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces in $\mathbb{R}^n$. Then

$$

\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) \le \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2).

$$

This is an immediate corollary of the preceding theorem. In HW3, we give a self-contained proof without using the preceding theorem.

2. **Subadditivity of rank function.** Let $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ be two matrices of the same order. Then

$$

\text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \le \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}).

$$

Proof: First claim trivially follows from the previous result or your own proof in HW3. For the second claim. First note $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \subseteq \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})$ (why?). Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \text{rank}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \\

&=& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(definition of rank)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) + \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(monotonicity of dim)} \\

&\le& \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{B})) \quad \text{(subadditivity of dim)} \\

&=& \text{rank}(\mathbf{A}) + \text{rank}(\mathbf{B}). \quad \text{(definition of rank)}

\end{eqnarray*}

The second inequality follows from the first claim.

- Two subspaces $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ in a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ are said to be **complementary** whenever

$$

\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2 \text{ and } \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}.

$$

In such cases, we say $\mathcal{V}$ is a **direct sum** of $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and denote $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

- TODO: visualize. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{a line}$. $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{space of symmetric vectors} \oplus \text{space of anti-symmetric vectors}$ (midterm).

- Let $\mathcal{S}_1, \mathcal{S}_2$ be two subspaces of same order and $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$. Following statements are equivalent:

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S}_1 \oplus \mathcal{S}_2$.

2. $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

3. Any vector $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be **uniquely** represented as

$$

\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x}_1 + \mathbf{x}_2, \text{ where } \mathbf{x}_1 \in \mathbf{S}_1, \mathbf{x}_2 \in \mathbf{S}_2.

$$

We will refer to this as the **unique representation** or **unique decomposition** property of direct sums.

Proof (optional): We show that $1 \Rightarrow 2 \Rightarrow 3 \Rightarrow 1$.

$1 \Rightarrow 2$: By definition of direct sum, we know $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Thus $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2) = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_2)$.

$2 \Rightarrow 3$: By 2, we know $\text{dim}(\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2) = 0$ so $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 + \mathcal{S}_2$ and assume $\mathbf{x}$ can be decomposed in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{u}_1 + \mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_1 + \mathbf{v}_2$, where $\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{v}_1 \in \mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2, \mathbf{v}_2 \in \mathcal{S}_2$. Then $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1 = -(\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2)$, indicating that the vectors $\mathbf{u}_1 - \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 - \mathbf{v}_2$ belong to both $\mathcal{S}_1$ and $\mathcal{S}_2$ and thus must be $\mathbf{0}$. Therefore $\mathbf{u}_1 = \mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{u}_2 = \mathbf{v}_2$.

$3 \Rightarrow 1$: We only need to show $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2 = \{\mathbf{0}\}$. Let $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$. Decompose $\mathbf{x}$ in two ways: $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{0} + \mathbf{x}$. Then by the uniqueness part of 3, $\mathbf{x}=\mathbf{0}$. So the only possible element in $\mathcal{S}_1 \cap \mathcal{S}_2$ is $\mathbf{0}$.

- An immediate corollary of the previous result is, for a matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$,

1. $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})$.

## Ortho-complementary subspaces

- An **orthocomplement set** of a set $\mathcal{X}$ (not necessarily a subspace) in a vector space $\mathcal{V} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$ is defined as

$$

\mathcal{X}^\perp = \{ \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{V}: \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{u} \rangle = 0 \text{ for all } \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X}\}.

$$

$\mathcal{X}^\perp$ is always a vector space regardless $\mathcal{X}$ is a vector space or not.

Proof: midterm.

- TODD: visualize $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{plan}^\perp$.

- **Direct sum theorem for orthocomplementary subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ with $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = m$. Then the following statements are true.

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. That is every vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expressed as $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$, where $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

2. $\mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp = \{\mathbf{0}\}$ (essentially disjoint).

3. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

4. $m = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}^\perp)$.

By the uniqueness of decomposition for direct sum, we know the expression of $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ is also **unique**.

Proof of 1: Let $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r\}$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{S}$ and extend it to an orthonormal basis $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r, \mathbf{z}_{r+1}, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_m\}$ of $\mathcal{V}$. Then any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expanded as

$$

\mathbf{y} = (\alpha_1 \mathbf{z}_1 + \cdots + \alpha_r \mathbf{z}_r) + (\alpha_{r+1} \mathbf{z}_{r+1} + \cdots + \alpha_m \mathbf{z}_m),

$$

where the first sum belongs to $\mathcal{S}$ and the second to $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 2: Suppose $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp$, then $\mathbf{x} \perp \mathbf{x}$, i.e., $\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle = 0$. Therefore $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$.

Proof of 3: Statement 1 says $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Statement 2 says $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$ are essentially disjoint. Thus $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 4: Follows from essential disjointness between $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## The fundamental theorem of linear algebra

- Let $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$. Then

1. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

3. $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 1: To show $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \text{ is orthogonal to columns of } \mathbf{A} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp.

\end{eqnarray*}

Then, $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 2: Since $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$ is a subspace, $(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp)^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

Proof of 3: Applying part 2 to $\mathbf{A}'$, we have

$$

\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') = \mathcal{N}((\mathbf{A}')')^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp

$$

and

$$

\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}').

$$

## Orthogonal projections

- An immediate corollary of the previous result is, for a matrix $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$,

1. $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})$.

## Ortho-complementary subspaces

- An **orthocomplement set** of a set $\mathcal{X}$ (not necessarily a subspace) in a vector space $\mathcal{V} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^m$ is defined as

$$

\mathcal{X}^\perp = \{ \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{V}: \langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{u} \rangle = 0 \text{ for all } \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{X}\}.

$$

$\mathcal{X}^\perp$ is always a vector space regardless $\mathcal{X}$ is a vector space or not.

Proof: midterm.

- TODD: visualize $\mathbb{R}^3 = \text{a plane} \oplus \text{plan}^\perp$.

- **Direct sum theorem for orthocomplementary subspaces.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ with $\text{dim}(\mathcal{V}) = m$. Then the following statements are true.

1. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. That is every vector $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expressed as $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$, where $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

2. $\mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp = \{\mathbf{0}\}$ (essentially disjoint).

3. $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

4. $m = \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}) + \text{dim}(\mathcal{S}^\perp)$.

By the uniqueness of decomposition for direct sum, we know the expression of $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ is also **unique**.

Proof of 1: Let $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r\}$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{S}$ and extend it to an orthonormal basis $\{\mathbf{z}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_r, \mathbf{z}_{r+1}, \ldots, \mathbf{z}_m\}$ of $\mathcal{V}$. Then any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$ can be expanded as

$$

\mathbf{y} = (\alpha_1 \mathbf{z}_1 + \cdots + \alpha_r \mathbf{z}_r) + (\alpha_{r+1} \mathbf{z}_{r+1} + \cdots + \alpha_m \mathbf{z}_m),

$$

where the first sum belongs to $\mathcal{S}$ and the second to $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 2: Suppose $\mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{S} \cap \mathcal{S}^\perp$, then $\mathbf{x} \perp \mathbf{x}$, i.e., $\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle = 0$. Therefore $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0}$.

Proof of 3: Statement 1 says $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} + \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Statement 2 says $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$ are essentially disjoint. Thus $\mathcal{V} = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$.

Proof of 4: Follows from essential disjointness between $\mathcal{S}$ and $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## The fundamental theorem of linear algebra

- Let $\mathbf{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$. Then

1. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

2. $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

3. $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$ and $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 1: To show $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}') \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{A}' \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{0} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \text{ is orthogonal to columns of } \mathbf{A} \\

&\Leftrightarrow& \mathbf{x} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp.

\end{eqnarray*}

Then, $\mathbb{R}^m = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')$.

Proof of 2: Since $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})$ is a subspace, $(\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A})^\perp)^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}')^\perp$.

Proof of 3: Applying part 2 to $\mathbf{A}'$, we have

$$

\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}') = \mathcal{N}((\mathbf{A}')')^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp

$$

and

$$

\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}) \oplus \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{A}').

$$

## Orthogonal projections

- Suppose $\mathcal{S}$ is a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. Let $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ be the unique representation of $\mathbf{y}$ with $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Then the vector $\mathbf{u}$ is called the **orthogonal projection** of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ (along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$).

- **The closest point theorem.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of some vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. The orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ is the **unique** point in $\mathcal{S}$ that is closest to $\mathbf{y}$. In other words, if $\mathbf{u}$ is the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$, then

$$

\|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 \le \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \text{ for all } \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S},

$$

with equality holding only when $\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{u}$.

Proof: Picture.

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + 2(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u})'(\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}) + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \quad \quad \quad (\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S}, \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp) \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&\ge& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Let $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$. A square matrix $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}}$ is called the **orthogonal porjector** into $\mathcal{S}$ if, for every $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}} \mathbf{y}$ is the projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

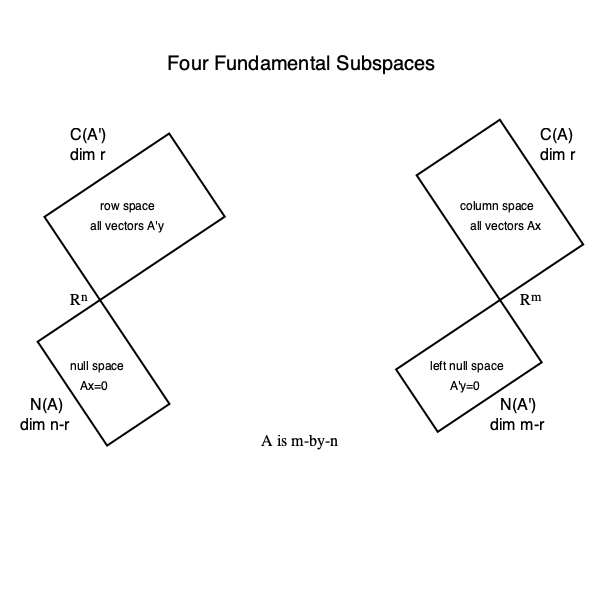

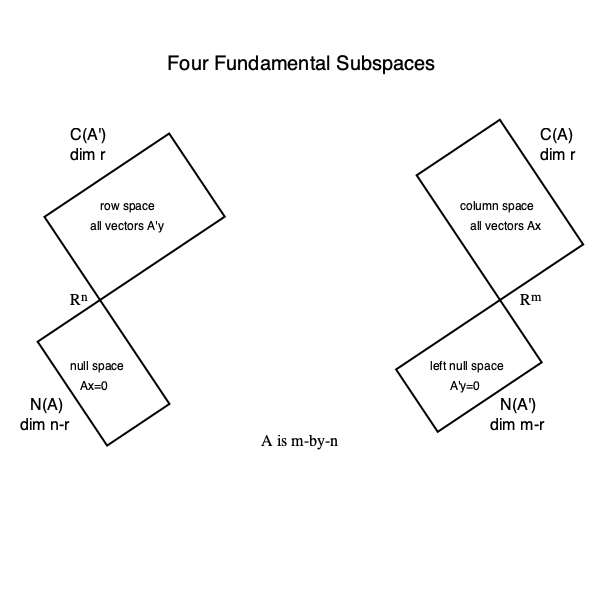

## Orthogonal projector into a column space

Let $\mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{x}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{x}_p \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$. We construct the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ using different ways.

### Method 1

Let $\mathbf{q}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{q}_r$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, e.g., by Gram-Schmidt with pivoting. Then

$$

\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}', \text{where } \mathbf{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{q}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{q}_r \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix},

$$

is the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we show $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} + (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y})$ such that $\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ and $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{X}')$.

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q}) = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X}).

$$

And

$$

\mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{0}_r

$$

thus $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{Q}') = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$.

### Method 2

- Suppose $\mathcal{S}$ is a subspace of a vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. Let $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$ be the unique representation of $\mathbf{y}$ with $\mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}$ and $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp$. Then the vector $\mathbf{u}$ is called the **orthogonal projection** of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ (along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$).

- **The closest point theorem.** Let $\mathcal{S}$ be a subspace of some vector space $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{V}$. The orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ is the **unique** point in $\mathcal{S}$ that is closest to $\mathbf{y}$. In other words, if $\mathbf{u}$ is the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$, then

$$

\|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 \le \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \text{ for all } \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S},

$$

with equality holding only when $\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{u}$.

Proof: Picture.

\begin{eqnarray*}

& & \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + 2(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u})'(\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}) + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \quad \quad \quad (\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{S}, \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u} \in \mathcal{S}^\perp) \\

&=& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2 + \|\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{w}\|^2 \\

&\ge& \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{u}\|^2.

\end{eqnarray*}

- Let $\mathbb{R}^n = \mathcal{S} \oplus \mathcal{S}^\perp$. A square matrix $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}}$ is called the **orthogonal porjector** into $\mathcal{S}$ if, for every $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, $\mathbf{P}_{\mathcal{S}} \mathbf{y}$ is the projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{S}$ along $\mathcal{S}^\perp$.

## Orthogonal projector into a column space

Let $\mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{x}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{x}_p \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}$. We construct the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ using different ways.

### Method 1

Let $\mathbf{q}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{q}_r$ be an orthonormal basis of $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, e.g., by Gram-Schmidt with pivoting. Then

$$

\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}', \text{where } \mathbf{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} | & & | \\ \mathbf{q}_1 & \dots & \mathbf{q}_r \\ | & & | \end{pmatrix},

$$

is the orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, we show $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} + (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y})$ such that $\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ and $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{X}')$.

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q}) = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X}).

$$

And

$$

\mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y}) = \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{0}_r

$$

thus $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{P} \mathbf{y} \in \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{Q}') = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{Q})^\perp = \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$.

### Method 2

1. The orthogonal projector of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$, where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ satisfies the **normal equation**

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Normal equation always has solution(s) (why?) and any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^-$ yields a solution $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$. Therefore,

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}'.

$$

for any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^-$.

2. If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, then the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}'.

$$

Proof of 1: Since the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ lives in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, thus can be written as $\mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$ for some $\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^p$. Furthermore, $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$ is orthogonal to any vectors in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ including the columns of $\mathbf{X}$. Thus

$$

\mathbf{X}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) = \mathbf{0},

$$

or equivalently,

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Proof of 2: If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, $\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X}$ is non-singular and the solution to the normal equation is uniquely determined by $\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$, and the orthogonal projection is $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$.

## Uniqueness of orthogonal projector

We have multiple ways to construct an orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$. This leaves the natural question: are orthogonal projectors into the same vector space unique? The answer is a happy yes.

- Theorem: Let $\mathbf{P}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{P}_2$ be two orthogonal projectors into a vector space $\mathcal{S}$. Then $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

Proof: By the uniqueness of the decomposition of direct sums, $\mathbf{P}_1 \mathbf{e}_i$ = $\mathbf{P}_2 \mathbf{e}_i$ for all $i$. Thus $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

## Any symmetric, idempotent matrix is an orthogonal projector

By the construction of orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}'$, we see $\mathbf{P}$ is symmetric and **idempotent**

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{P}.

$$

It turns out the reverse is also true.

- Theorem: Any symmetric, idemponent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, let $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w}$, where $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ and $\mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}') = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P})$. Since $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$, $\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u}$ for some $\mathbf{u} \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Then $\mathbf{P}\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{v}$. Thus $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

1. The orthogonal projector of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$, where $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ satisfies the **normal equation**

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Normal equation always has solution(s) (why?) and any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^-$ yields a solution $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}'\mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$. Therefore,

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^- \mathbf{X}'.

$$

for any generalized inverse $(\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^-$.

2. If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, then the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ is given by

$$

\mathbf{P}_{\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}'.

$$

Proof of 1: Since the orthogonal projection of $\mathbf{y}$ into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ lives in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$, thus can be written as $\mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}$ for some $\boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^p$. Furthermore, $\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})^\perp$ is orthogonal to any vectors in $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$ including the columns of $\mathbf{X}$. Thus

$$

\mathbf{X}' (\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta}) = \mathbf{0},

$$

or equivalently,

$$

\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}.

$$

Proof of 2: If $\mathbf{X}$ has full column rank, $\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X}$ is non-singular and the solution to the normal equation is uniquely determined by $\boldsymbol{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$, and the orthogonal projection is $\mathbf{u} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} = \mathbf{X} (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{y}$.

## Uniqueness of orthogonal projector

We have multiple ways to construct an orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{X})$. This leaves the natural question: are orthogonal projectors into the same vector space unique? The answer is a happy yes.

- Theorem: Let $\mathbf{P}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{P}_2$ be two orthogonal projectors into a vector space $\mathcal{S}$. Then $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

Proof: By the uniqueness of the decomposition of direct sums, $\mathbf{P}_1 \mathbf{e}_i$ = $\mathbf{P}_2 \mathbf{e}_i$ for all $i$. Thus $\mathbf{P}_{1}=\mathbf{P}_2$.

## Any symmetric, idempotent matrix is an orthogonal projector

By the construction of orthogonal projector $\mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}'$, we see $\mathbf{P}$ is symmetric and **idempotent**

$$

\mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{Q}' = \mathbf{P}.

$$

It turns out the reverse is also true.

- Theorem: Any symmetric, idemponent matrix $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.

Proof: For any $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, let $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{w}$, where $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$ and $\mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})^\perp = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P}') = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{P})$. Since $\mathbf{v} \in \mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$, $\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u}$ for some $\mathbf{u} \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Then $\mathbf{P}\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{P} \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{P}\mathbf{w} = \mathbf{v} + \mathbf{0} = \mathbf{v}$. Thus $\mathbf{P}$ is the orthogonal projector into $\mathcal{C}(\mathbf{P})$.