---

title: 'Computer Languages (R, Python, Julia, C/C++)'

subtitle: Biostat/Biomath M257

author: Dr. Hua Zhou @ UCLA

date: today

format:

html:

theme: cosmo

embed-resources: true

number-sections: true

toc: true

toc-depth: 4

toc-location: left

code-fold: false

jupyter:

jupytext:

formats: 'ipynb,qmd'

text_representation:

extension: .qmd

format_name: quarto

format_version: '1.0'

jupytext_version: 1.14.5

kernelspec:

display_name: Julia (8 threads) 1.8.5

language: julia

name: julia-_8-threads_-1.8

---

System information (for reproducibility):

```{julia}

versioninfo()

```

Load packages:

```{julia}

using Pkg

Pkg.activate(pwd())

Pkg.instantiate()

Pkg.status()

```

In this lecture, we review some popular computer languages commonly used in computational statistics. We want to understand why some languages are faster than others and what are the remedies for the slow languages.

## Types of computer languages

* **Compiled languages** (low-level languages): C/C++, Fortran, ...

- Directly compiled to machine code that is executed by CPU

- Pros: fast, memory efficient

- Cons: longer development time, hard to debug

* **Interpreted language** (high-level languages): R, Matlab, Python, SAS IML, JavaScript, ...

- Interpreted by interpreter

- Pros: fast prototyping

- Cons: excruciatingly slow for loops

* Mixed (dynamic) languages: Matlab (JIT), R (`compiler` package), Julia, Cython, JAVA, ...

- Pros and cons: between the compiled and interpreted languages

* Script languages: Linux shell scripts, Perl, ...

- Extremely useful for some data preprocessing and manipulation

* Database languages: SQL, Hive (Hadoop).

- Data analysis *never* happens if we do not know how to retrieve data from databases

[203B (Introduction to Data Science)](https://ucla-biostat-203b.github.io/2023winter/schedule/schedule.html) covers some basics on scripting and database.

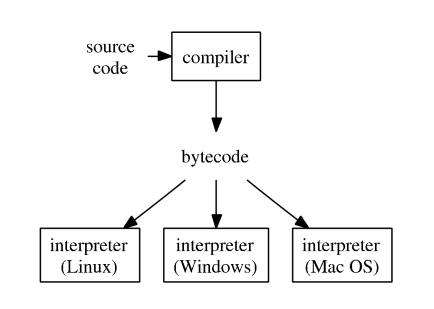

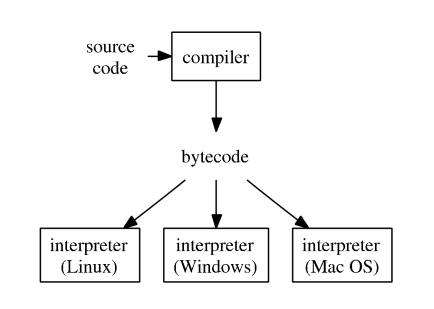

## How high-level languages work?

Comics: [The Life of a Bytecode Language](https://betterprogramming.pub/the-life-of-a-bytecode-language-fca666928e7b)

- Typical execution of a high-level language such as R, Python, and Matlab.

- To improve efficiency of interpreted languages such as R or Matlab, conventional wisdom is to avoid loops as much as possible. Aka, **vectorize code**

> The only loop you are allowed to have is that for an iterative algorithm.

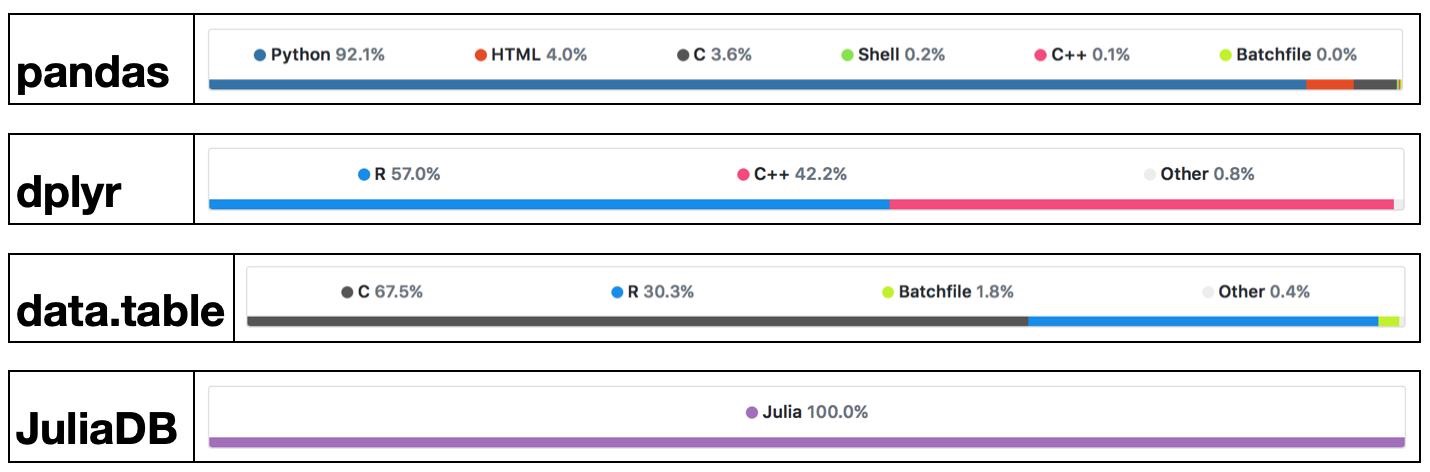

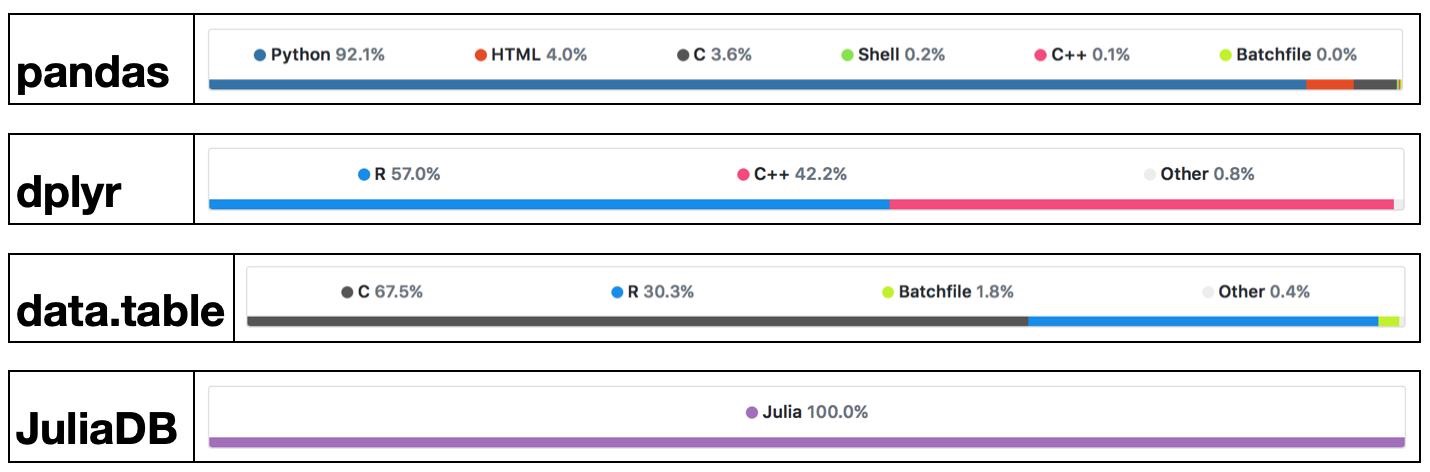

- When looping is unavoidable, need to code in C, C++, or Fortran. This creates the notorious **two language problem**

Success stories: the popular `glmnet` package in R is coded in Fortran; `tidyverse` and `data.table` packages use a lot RCpp/C++.

- To improve efficiency of interpreted languages such as R or Matlab, conventional wisdom is to avoid loops as much as possible. Aka, **vectorize code**

> The only loop you are allowed to have is that for an iterative algorithm.

- When looping is unavoidable, need to code in C, C++, or Fortran. This creates the notorious **two language problem**

Success stories: the popular `glmnet` package in R is coded in Fortran; `tidyverse` and `data.table` packages use a lot RCpp/C++.

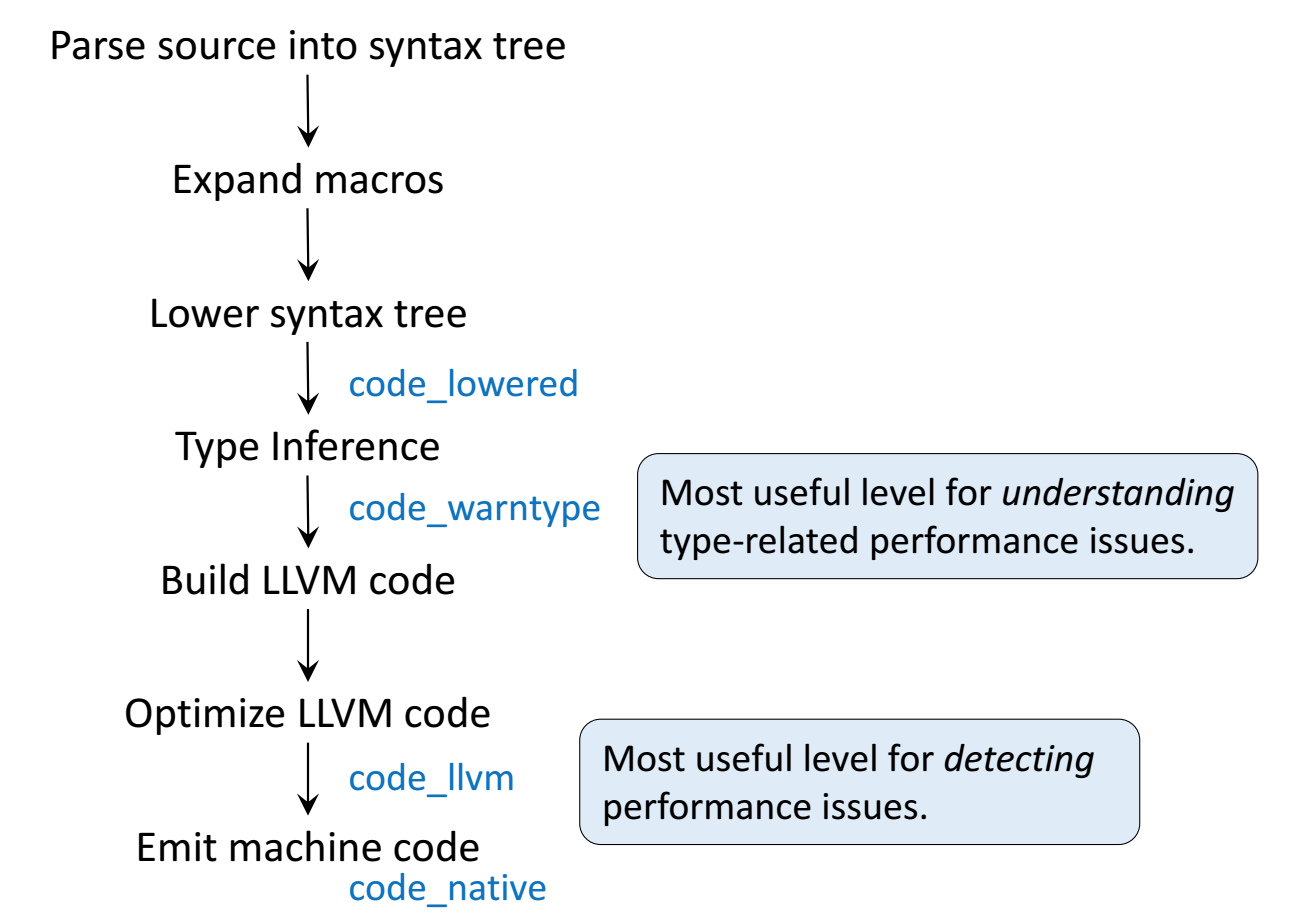

- High-level languages have made many efforts to bring themselves closer to the performance of low-level languages such as C, C++, or Fortran, with a variety levels of success.

- Matlab has employed JIT (just-in-time compilation) technology since 2002.

- Since R 3.4.0 (Apr 2017), the JIT bytecode compiler is enabled by default at its level 3.

- Cython is a compiler system based on Python.

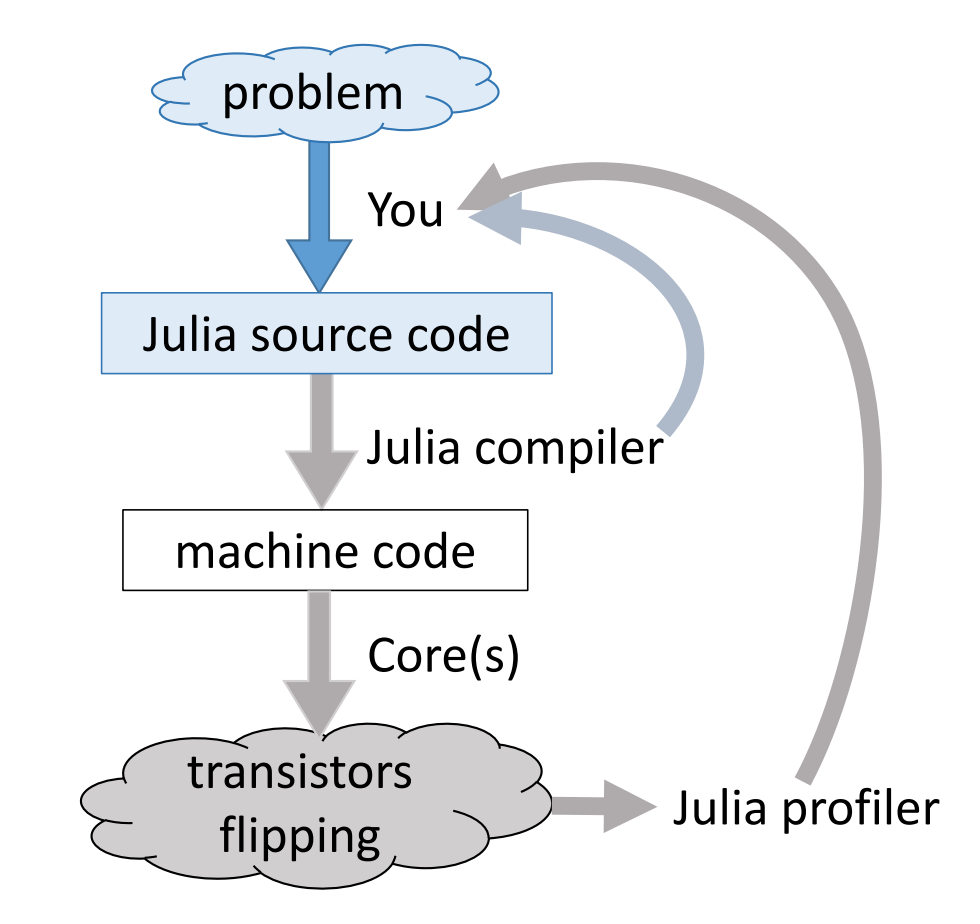

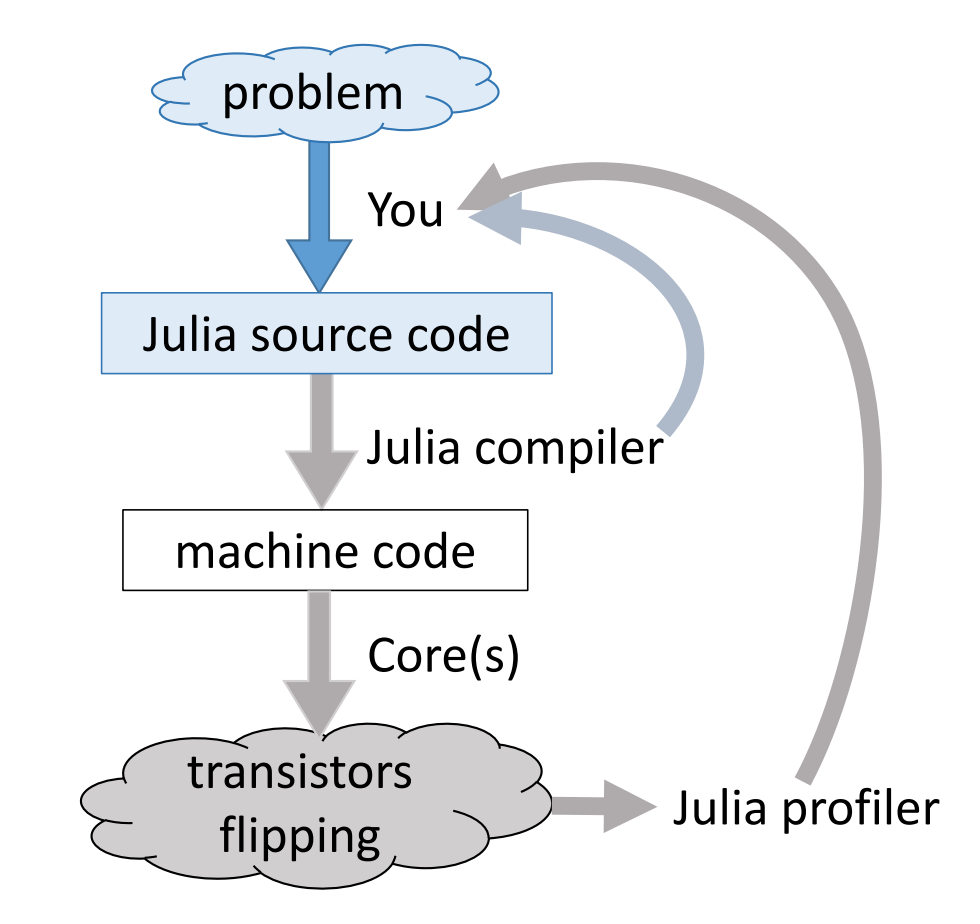

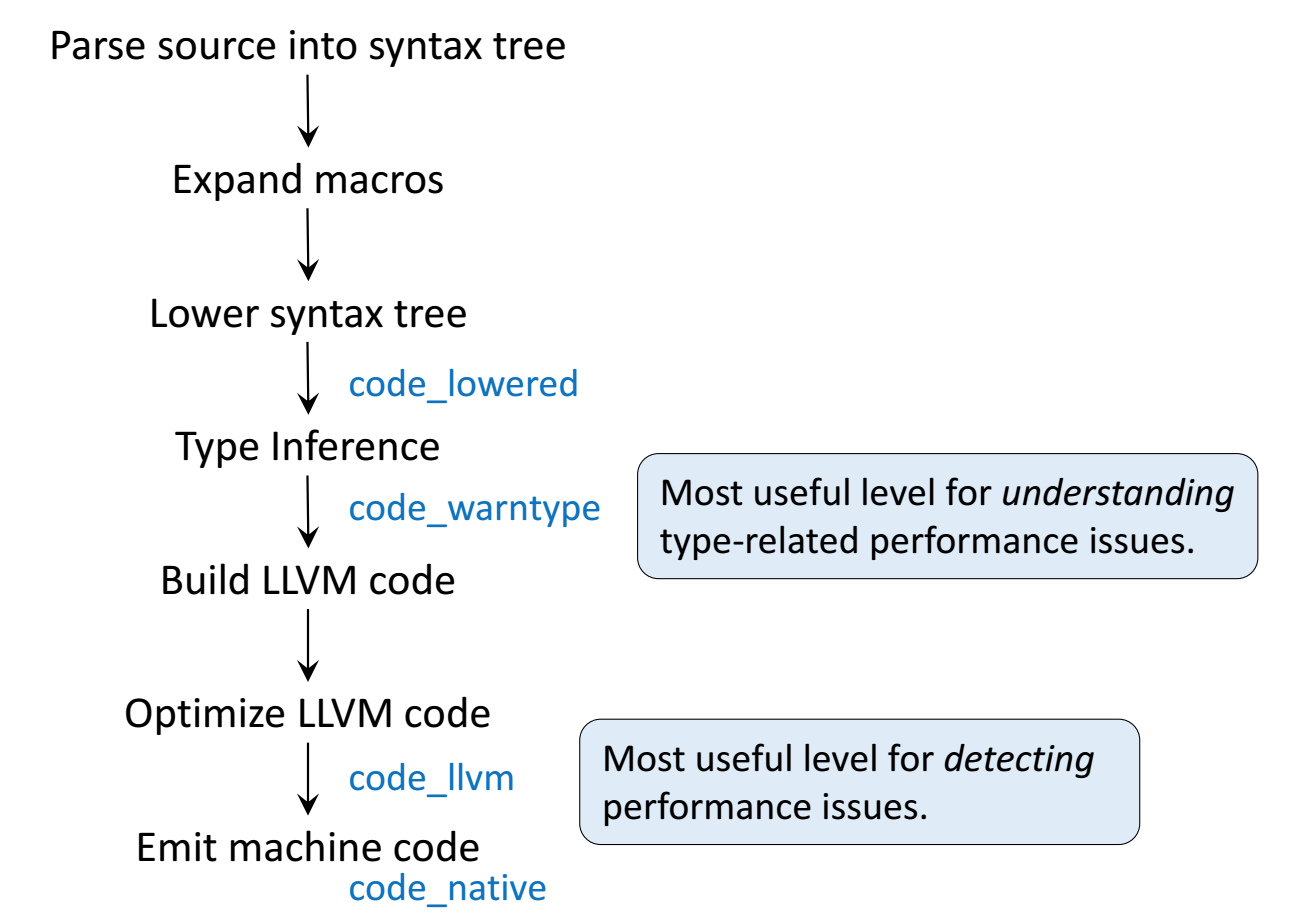

- Modern languages such as Julia tries to solve the two language problem. That is to achieve efficiency without vectorizing code.

- Julia execution.

- High-level languages have made many efforts to bring themselves closer to the performance of low-level languages such as C, C++, or Fortran, with a variety levels of success.

- Matlab has employed JIT (just-in-time compilation) technology since 2002.

- Since R 3.4.0 (Apr 2017), the JIT bytecode compiler is enabled by default at its level 3.

- Cython is a compiler system based on Python.

- Modern languages such as Julia tries to solve the two language problem. That is to achieve efficiency without vectorizing code.

- Julia execution.

## Gibbs sampler example by Doug Bates

- Doug Bates (member of R-Core, author of popular R packages `Matrix`, `lme4`, `RcppEigen`, etc)

> As some of you may know, I have had a (rather late) mid-life crisis and run off with another language called Julia.

>

> -- Doug Bates (on the `knitr` Google Group)

- An example from Dr. Doug Bates's slides [Julia for R Programmers](http://www.stat.wisc.edu/~bates/JuliaForRProgrammers.pdf).

- The task is to create a Gibbs sampler for the density

$$

f(x, y) = k x^2 \exp(- x y^2 - y^2 + 2y - 4x), \quad x > 0

$$

using the conditional distributions

$$

\begin{eqnarray*}

X | Y &\sim& \Gamma \left( 3, \frac{1}{y^2 + 4} \right) \\

Y | X &\sim& N \left(\frac{1}{1+x}, \frac{1}{2(1+x)} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

$$

* R solution. The `RCall.jl` package allows us to execute R code without leaving the `Julia` environment. We first define an R function `Rgibbs()`.

```{julia}

using RCall

# show R information

R"""

sessionInfo()

"""

```

```{julia}

# define a function for Gibbs sampling

R"""

library(Matrix)

Rgibbs <- function(N, thin) {

mat <- matrix(0, nrow=N, ncol=2)

x <- y <- 0

for (i in 1:N) {

for (j in 1:thin) {

x <- rgamma(1, 3, y * y + 4) # 3rd arg is rate

y <- rnorm(1, 1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2 * (x + 1)))

}

mat[i,] <- c(x, y)

}

mat

}

"""

```

To generate a sample of size 10,000 with a thinning of 500. How long does it take?

```{julia}

R"""

system.time(Rgibbs(10000, 500))

"""

```

* This is a Julia function for the same Gibbs sampler:

```{julia}

using Distributions

function jgibbs(N, thin)

mat = zeros(N, 2)

x = y = 0.0

for i in 1:N

for j in 1:thin

x = rand(Gamma(3, 1 / (y * y + 4)))

y = rand(Normal(1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2(x + 1))))

end

mat[i, 1] = x

mat[i, 2] = y

end

mat

end

```

Generate the same number of samples. How long does it take?

```{julia}

jgibbs(100, 5); # warm-up

@elapsed jgibbs(10000, 500)

```

We see 40-80 fold speed up of `Julia` over `R` on this example, **with similar coding effort**!

## Comparing C, C++, R, Python, and Julia

To better understand how these languages work, we consider a simple task: summing a vector.

Let's first generate data: 1 million double precision numbers from uniform [0, 1].

```{julia}

using Random

Random.seed!(257) # seed

x = rand(1_000_000) # 1 million random numbers in [0, 1)

sum(x)

```

In this class, we extensively use package `BenchmarkTools.jl` for robust benchmarking. It's the analog of the `microbenchmark` or `bench` package in R.

```{julia}

using BenchmarkTools

```

### C

We would use the low-level C code as the baseline for copmarison. In Julia, we can easily run compiled C code using the `ccall` function.

```{julia}

using Libdl

C_code = """

#include

double c_sum(size_t n, double *X) {

double s = 0.0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

s += X[i];

}

return s;

}

"""

const Clib = tempname() # make a temporary file

# compile to a shared library by piping C_code to gcc

# (works only if you have gcc installed):

open(`gcc -std=c99 -fPIC -O3 -msse3 -xc -shared -o $(Clib * "." * Libdl.dlext) -`, "w") do f

print(f, C_code)

end

# define a Julia function that calls the C function:

c_sum(X :: Array{Float64}) = ccall(("c_sum", Clib), Float64, (Csize_t, Ptr{Float64}), length(X), X)

```

```{julia}

# make sure it gives same answer

c_sum(x)

```

```{julia}

# dollar sign to interpolate array x into local scope for benchmarking

bm = @benchmark c_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

# a dictionary to store median runtime (in milliseconds)

benchmark_result = Dict()

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

benchmark_result["C"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### R, buildin sum

Next we compare to the build in `sum` function in R, which is implemented using C.

```{julia}

R"""

library(bench)

library(tidyverse)

# interpolate x into R workspace

y <- $x

rbm_builtin <- bench::mark(sum(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_builtin # dataframe

benchmark_result["R builtin"] = median(rbm_builtin[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### R, handwritten loop

Handwritten loop in R is much slower.

```{julia}

R"""

sum_r <- function(x) {

s <- 0

for (xi in x) {

s <- s + xi

}

s

}

library(bench)

y <- $x

rbm_loop <- bench::mark(sum_r(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_loop # dataframe

benchmark_result["R loop"] = median(rbm_loop[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### R, Rcpp

Rcpp package provides an easy way to incorporate C++ code in R.

```{julia}

R"""

library(Rcpp)

cppFunction('double rcpp_sum(NumericVector x) {

int n = x.size();

double total = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

total += x[i];

}

return total;

}')

rcpp_sum

"""

```

```{julia}

R"""

rbm_rcpp <- bench::mark(rcpp_sum(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_rcpp # dataframe

benchmark_result["R Rcpp"] = median(rbm_rcpp[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### Python, builtin sum

Built in function `sum` in Python.

```{julia}

using PyCall

PyCall.pyversion

```

```{julia}

# get the Python built-in "sum" function:

pysum = pybuiltin("sum")

bm = @benchmark $pysum($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python builtin"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Python, handwritten loop

```{julia}

py"""

def py_sum(A):

s = 0.0

for a in A:

s += a

return s

"""

sum_py = py"py_sum"

bm = @benchmark $sum_py($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python loop"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Python, numpy

Numpy is the high-performance scientific computing library for Python.

```{julia}

# bring in sum function from Numpy

numpy_sum = pyimport("numpy")."sum"

```

```{julia}

bm = @benchmark $numpy_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python numpy"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

Numpy performance is on a par with Julia build-in sum function. Both are about 3 times faster than C, possibly because of usage of [SIMD](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIMD).

### Julia, builtin sum

`@time`, `@elapsed`, `@allocated` macros in Julia report run times and memory allocation.

```{julia}

@time sum(x) # no compilation time after first run

```

For more robust benchmarking, we use BenchmarkTools.jl package.

```{julia}

bm = @benchmark sum($x)

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia builtin"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Julia, handwritten loop

Let's also write a loop and benchmark.

```{julia}

function jl_sum(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

for a in A

s += a

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia loop"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

**Exercise**: annotate the loop by [`@simd`](https://docs.julialang.org/en/v1/manual/performance-tips/#man-performance-annotations-1) or `LoopVectorization.@turbo` and benchmark again.

```{julia}

using LoopVectorization

function jl_sum_turbo(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

@turbo for i in eachindex(A)

s += A[i]

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum_turbo($x)

bm

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia turbo"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

`@tturbo` macro turns on multi-threading. Not for this to function, Julia needs to be started with multi-threading.

```{julia}

function jl_sum_tturbo(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

@tturbo for i in eachindex(A)

s += A[i]

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum_tturbo($x)

bm

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia tturbo"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Summary

```{julia}

sort(collect(benchmark_result), by = x -> x[2])

```

* `C`, `R builtin` are the baseline C performance (gold standard).

* `Python builtin` and `Python loop` are >50 fold slower than C because the loop is interpreted.

* `R loop` is about 10 times slower than C and indicates the performance of JIT bytecode generated by its `compiler` package (turned on by default since R v3.4.0 (Apr 2017)).

* `Julia loop` is close to C performance, because Julia code is JIT compiled.

* `Julia builtin`, `Python numpy`, and `Julia turbo` are 4-5 fold faster than C because of SIMD.

* `@turbo` (SIMD) and `@tturbo` (multithreading+SIMD), offered by the LoopVectorization.jl package. yields the top performance on this machine.

## Take home message for computational scientists

- High-level language (R, Python, Matlab) programmers should be familiar with existing high-performance packages. Don't reinvent wheels.

- R: RcppEigen, tidyverse, ...

- Python: numpy, scipy, ...

- In most research projects, looping is unavoidable. Then we need to use a low-level language.

- R: Rcpp, ...

- Python: Cython, ...

- In this course, we use Julia, which circumvents the two language problem. So we can spend more time on algorithms, not on juggling $\ge 2$ languages.

## Gibbs sampler example by Doug Bates

- Doug Bates (member of R-Core, author of popular R packages `Matrix`, `lme4`, `RcppEigen`, etc)

> As some of you may know, I have had a (rather late) mid-life crisis and run off with another language called Julia.

>

> -- Doug Bates (on the `knitr` Google Group)

- An example from Dr. Doug Bates's slides [Julia for R Programmers](http://www.stat.wisc.edu/~bates/JuliaForRProgrammers.pdf).

- The task is to create a Gibbs sampler for the density

$$

f(x, y) = k x^2 \exp(- x y^2 - y^2 + 2y - 4x), \quad x > 0

$$

using the conditional distributions

$$

\begin{eqnarray*}

X | Y &\sim& \Gamma \left( 3, \frac{1}{y^2 + 4} \right) \\

Y | X &\sim& N \left(\frac{1}{1+x}, \frac{1}{2(1+x)} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

$$

* R solution. The `RCall.jl` package allows us to execute R code without leaving the `Julia` environment. We first define an R function `Rgibbs()`.

```{julia}

using RCall

# show R information

R"""

sessionInfo()

"""

```

```{julia}

# define a function for Gibbs sampling

R"""

library(Matrix)

Rgibbs <- function(N, thin) {

mat <- matrix(0, nrow=N, ncol=2)

x <- y <- 0

for (i in 1:N) {

for (j in 1:thin) {

x <- rgamma(1, 3, y * y + 4) # 3rd arg is rate

y <- rnorm(1, 1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2 * (x + 1)))

}

mat[i,] <- c(x, y)

}

mat

}

"""

```

To generate a sample of size 10,000 with a thinning of 500. How long does it take?

```{julia}

R"""

system.time(Rgibbs(10000, 500))

"""

```

* This is a Julia function for the same Gibbs sampler:

```{julia}

using Distributions

function jgibbs(N, thin)

mat = zeros(N, 2)

x = y = 0.0

for i in 1:N

for j in 1:thin

x = rand(Gamma(3, 1 / (y * y + 4)))

y = rand(Normal(1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2(x + 1))))

end

mat[i, 1] = x

mat[i, 2] = y

end

mat

end

```

Generate the same number of samples. How long does it take?

```{julia}

jgibbs(100, 5); # warm-up

@elapsed jgibbs(10000, 500)

```

We see 40-80 fold speed up of `Julia` over `R` on this example, **with similar coding effort**!

## Comparing C, C++, R, Python, and Julia

To better understand how these languages work, we consider a simple task: summing a vector.

Let's first generate data: 1 million double precision numbers from uniform [0, 1].

```{julia}

using Random

Random.seed!(257) # seed

x = rand(1_000_000) # 1 million random numbers in [0, 1)

sum(x)

```

In this class, we extensively use package `BenchmarkTools.jl` for robust benchmarking. It's the analog of the `microbenchmark` or `bench` package in R.

```{julia}

using BenchmarkTools

```

### C

We would use the low-level C code as the baseline for copmarison. In Julia, we can easily run compiled C code using the `ccall` function.

```{julia}

using Libdl

C_code = """

#include

double c_sum(size_t n, double *X) {

double s = 0.0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

s += X[i];

}

return s;

}

"""

const Clib = tempname() # make a temporary file

# compile to a shared library by piping C_code to gcc

# (works only if you have gcc installed):

open(`gcc -std=c99 -fPIC -O3 -msse3 -xc -shared -o $(Clib * "." * Libdl.dlext) -`, "w") do f

print(f, C_code)

end

# define a Julia function that calls the C function:

c_sum(X :: Array{Float64}) = ccall(("c_sum", Clib), Float64, (Csize_t, Ptr{Float64}), length(X), X)

```

```{julia}

# make sure it gives same answer

c_sum(x)

```

```{julia}

# dollar sign to interpolate array x into local scope for benchmarking

bm = @benchmark c_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

# a dictionary to store median runtime (in milliseconds)

benchmark_result = Dict()

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

benchmark_result["C"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### R, buildin sum

Next we compare to the build in `sum` function in R, which is implemented using C.

```{julia}

R"""

library(bench)

library(tidyverse)

# interpolate x into R workspace

y <- $x

rbm_builtin <- bench::mark(sum(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_builtin # dataframe

benchmark_result["R builtin"] = median(rbm_builtin[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### R, handwritten loop

Handwritten loop in R is much slower.

```{julia}

R"""

sum_r <- function(x) {

s <- 0

for (xi in x) {

s <- s + xi

}

s

}

library(bench)

y <- $x

rbm_loop <- bench::mark(sum_r(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_loop # dataframe

benchmark_result["R loop"] = median(rbm_loop[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### R, Rcpp

Rcpp package provides an easy way to incorporate C++ code in R.

```{julia}

R"""

library(Rcpp)

cppFunction('double rcpp_sum(NumericVector x) {

int n = x.size();

double total = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

total += x[i];

}

return total;

}')

rcpp_sum

"""

```

```{julia}

R"""

rbm_rcpp <- bench::mark(rcpp_sum(y)) %>%

print(width = Inf)

""";

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in milliseconds)

@rget rbm_rcpp # dataframe

benchmark_result["R Rcpp"] = median(rbm_rcpp[!, :median]) * 1000

```

### Python, builtin sum

Built in function `sum` in Python.

```{julia}

using PyCall

PyCall.pyversion

```

```{julia}

# get the Python built-in "sum" function:

pysum = pybuiltin("sum")

bm = @benchmark $pysum($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python builtin"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Python, handwritten loop

```{julia}

py"""

def py_sum(A):

s = 0.0

for a in A:

s += a

return s

"""

sum_py = py"py_sum"

bm = @benchmark $sum_py($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python loop"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Python, numpy

Numpy is the high-performance scientific computing library for Python.

```{julia}

# bring in sum function from Numpy

numpy_sum = pyimport("numpy")."sum"

```

```{julia}

bm = @benchmark $numpy_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

# store median runtime (in miliseconds)

benchmark_result["Python numpy"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

Numpy performance is on a par with Julia build-in sum function. Both are about 3 times faster than C, possibly because of usage of [SIMD](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIMD).

### Julia, builtin sum

`@time`, `@elapsed`, `@allocated` macros in Julia report run times and memory allocation.

```{julia}

@time sum(x) # no compilation time after first run

```

For more robust benchmarking, we use BenchmarkTools.jl package.

```{julia}

bm = @benchmark sum($x)

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia builtin"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Julia, handwritten loop

Let's also write a loop and benchmark.

```{julia}

function jl_sum(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

for a in A

s += a

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum($x)

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia loop"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

**Exercise**: annotate the loop by [`@simd`](https://docs.julialang.org/en/v1/manual/performance-tips/#man-performance-annotations-1) or `LoopVectorization.@turbo` and benchmark again.

```{julia}

using LoopVectorization

function jl_sum_turbo(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

@turbo for i in eachindex(A)

s += A[i]

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum_turbo($x)

bm

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia turbo"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

`@tturbo` macro turns on multi-threading. Not for this to function, Julia needs to be started with multi-threading.

```{julia}

function jl_sum_tturbo(A)

s = zero(eltype(A))

@tturbo for i in eachindex(A)

s += A[i]

end

s

end

bm = @benchmark jl_sum_tturbo($x)

bm

```

```{julia}

benchmark_result["Julia tturbo"] = median(bm.times) / 1e6

```

### Summary

```{julia}

sort(collect(benchmark_result), by = x -> x[2])

```

* `C`, `R builtin` are the baseline C performance (gold standard).

* `Python builtin` and `Python loop` are >50 fold slower than C because the loop is interpreted.

* `R loop` is about 10 times slower than C and indicates the performance of JIT bytecode generated by its `compiler` package (turned on by default since R v3.4.0 (Apr 2017)).

* `Julia loop` is close to C performance, because Julia code is JIT compiled.

* `Julia builtin`, `Python numpy`, and `Julia turbo` are 4-5 fold faster than C because of SIMD.

* `@turbo` (SIMD) and `@tturbo` (multithreading+SIMD), offered by the LoopVectorization.jl package. yields the top performance on this machine.

## Take home message for computational scientists

- High-level language (R, Python, Matlab) programmers should be familiar with existing high-performance packages. Don't reinvent wheels.

- R: RcppEigen, tidyverse, ...

- Python: numpy, scipy, ...

- In most research projects, looping is unavoidable. Then we need to use a low-level language.

- R: Rcpp, ...

- Python: Cython, ...

- In this course, we use Julia, which circumvents the two language problem. So we can spend more time on algorithms, not on juggling $\ge 2$ languages.

- To improve efficiency of interpreted languages such as R or Matlab, conventional wisdom is to avoid loops as much as possible. Aka, **vectorize code**

> The only loop you are allowed to have is that for an iterative algorithm.

- When looping is unavoidable, need to code in C, C++, or Fortran. This creates the notorious **two language problem**

Success stories: the popular `glmnet` package in R is coded in Fortran; `tidyverse` and `data.table` packages use a lot RCpp/C++.

- To improve efficiency of interpreted languages such as R or Matlab, conventional wisdom is to avoid loops as much as possible. Aka, **vectorize code**

> The only loop you are allowed to have is that for an iterative algorithm.

- When looping is unavoidable, need to code in C, C++, or Fortran. This creates the notorious **two language problem**

Success stories: the popular `glmnet` package in R is coded in Fortran; `tidyverse` and `data.table` packages use a lot RCpp/C++.

- High-level languages have made many efforts to bring themselves closer to the performance of low-level languages such as C, C++, or Fortran, with a variety levels of success.

- Matlab has employed JIT (just-in-time compilation) technology since 2002.

- Since R 3.4.0 (Apr 2017), the JIT bytecode compiler is enabled by default at its level 3.

- Cython is a compiler system based on Python.

- Modern languages such as Julia tries to solve the two language problem. That is to achieve efficiency without vectorizing code.

- Julia execution.

- High-level languages have made many efforts to bring themselves closer to the performance of low-level languages such as C, C++, or Fortran, with a variety levels of success.

- Matlab has employed JIT (just-in-time compilation) technology since 2002.

- Since R 3.4.0 (Apr 2017), the JIT bytecode compiler is enabled by default at its level 3.

- Cython is a compiler system based on Python.

- Modern languages such as Julia tries to solve the two language problem. That is to achieve efficiency without vectorizing code.

- Julia execution.

## Gibbs sampler example by Doug Bates

- Doug Bates (member of R-Core, author of popular R packages `Matrix`, `lme4`, `RcppEigen`, etc)

> As some of you may know, I have had a (rather late) mid-life crisis and run off with another language called Julia.

>

> -- Doug Bates (on the `knitr` Google Group)

- An example from Dr. Doug Bates's slides [Julia for R Programmers](http://www.stat.wisc.edu/~bates/JuliaForRProgrammers.pdf).

- The task is to create a Gibbs sampler for the density

$$

f(x, y) = k x^2 \exp(- x y^2 - y^2 + 2y - 4x), \quad x > 0

$$

using the conditional distributions

$$

\begin{eqnarray*}

X | Y &\sim& \Gamma \left( 3, \frac{1}{y^2 + 4} \right) \\

Y | X &\sim& N \left(\frac{1}{1+x}, \frac{1}{2(1+x)} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

$$

* R solution. The `RCall.jl` package allows us to execute R code without leaving the `Julia` environment. We first define an R function `Rgibbs()`.

```{julia}

using RCall

# show R information

R"""

sessionInfo()

"""

```

```{julia}

# define a function for Gibbs sampling

R"""

library(Matrix)

Rgibbs <- function(N, thin) {

mat <- matrix(0, nrow=N, ncol=2)

x <- y <- 0

for (i in 1:N) {

for (j in 1:thin) {

x <- rgamma(1, 3, y * y + 4) # 3rd arg is rate

y <- rnorm(1, 1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2 * (x + 1)))

}

mat[i,] <- c(x, y)

}

mat

}

"""

```

To generate a sample of size 10,000 with a thinning of 500. How long does it take?

```{julia}

R"""

system.time(Rgibbs(10000, 500))

"""

```

* This is a Julia function for the same Gibbs sampler:

```{julia}

using Distributions

function jgibbs(N, thin)

mat = zeros(N, 2)

x = y = 0.0

for i in 1:N

for j in 1:thin

x = rand(Gamma(3, 1 / (y * y + 4)))

y = rand(Normal(1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2(x + 1))))

end

mat[i, 1] = x

mat[i, 2] = y

end

mat

end

```

Generate the same number of samples. How long does it take?

```{julia}

jgibbs(100, 5); # warm-up

@elapsed jgibbs(10000, 500)

```

We see 40-80 fold speed up of `Julia` over `R` on this example, **with similar coding effort**!

## Comparing C, C++, R, Python, and Julia

To better understand how these languages work, we consider a simple task: summing a vector.

Let's first generate data: 1 million double precision numbers from uniform [0, 1].

```{julia}

using Random

Random.seed!(257) # seed

x = rand(1_000_000) # 1 million random numbers in [0, 1)

sum(x)

```

In this class, we extensively use package `BenchmarkTools.jl` for robust benchmarking. It's the analog of the `microbenchmark` or `bench` package in R.

```{julia}

using BenchmarkTools

```

### C

We would use the low-level C code as the baseline for copmarison. In Julia, we can easily run compiled C code using the `ccall` function.

```{julia}

using Libdl

C_code = """

#include

## Gibbs sampler example by Doug Bates

- Doug Bates (member of R-Core, author of popular R packages `Matrix`, `lme4`, `RcppEigen`, etc)

> As some of you may know, I have had a (rather late) mid-life crisis and run off with another language called Julia.

>

> -- Doug Bates (on the `knitr` Google Group)

- An example from Dr. Doug Bates's slides [Julia for R Programmers](http://www.stat.wisc.edu/~bates/JuliaForRProgrammers.pdf).

- The task is to create a Gibbs sampler for the density

$$

f(x, y) = k x^2 \exp(- x y^2 - y^2 + 2y - 4x), \quad x > 0

$$

using the conditional distributions

$$

\begin{eqnarray*}

X | Y &\sim& \Gamma \left( 3, \frac{1}{y^2 + 4} \right) \\

Y | X &\sim& N \left(\frac{1}{1+x}, \frac{1}{2(1+x)} \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

$$

* R solution. The `RCall.jl` package allows us to execute R code without leaving the `Julia` environment. We first define an R function `Rgibbs()`.

```{julia}

using RCall

# show R information

R"""

sessionInfo()

"""

```

```{julia}

# define a function for Gibbs sampling

R"""

library(Matrix)

Rgibbs <- function(N, thin) {

mat <- matrix(0, nrow=N, ncol=2)

x <- y <- 0

for (i in 1:N) {

for (j in 1:thin) {

x <- rgamma(1, 3, y * y + 4) # 3rd arg is rate

y <- rnorm(1, 1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2 * (x + 1)))

}

mat[i,] <- c(x, y)

}

mat

}

"""

```

To generate a sample of size 10,000 with a thinning of 500. How long does it take?

```{julia}

R"""

system.time(Rgibbs(10000, 500))

"""

```

* This is a Julia function for the same Gibbs sampler:

```{julia}

using Distributions

function jgibbs(N, thin)

mat = zeros(N, 2)

x = y = 0.0

for i in 1:N

for j in 1:thin

x = rand(Gamma(3, 1 / (y * y + 4)))

y = rand(Normal(1 / (x + 1), 1 / sqrt(2(x + 1))))

end

mat[i, 1] = x

mat[i, 2] = y

end

mat

end

```

Generate the same number of samples. How long does it take?

```{julia}

jgibbs(100, 5); # warm-up

@elapsed jgibbs(10000, 500)

```

We see 40-80 fold speed up of `Julia` over `R` on this example, **with similar coding effort**!

## Comparing C, C++, R, Python, and Julia

To better understand how these languages work, we consider a simple task: summing a vector.

Let's first generate data: 1 million double precision numbers from uniform [0, 1].

```{julia}

using Random

Random.seed!(257) # seed

x = rand(1_000_000) # 1 million random numbers in [0, 1)

sum(x)

```

In this class, we extensively use package `BenchmarkTools.jl` for robust benchmarking. It's the analog of the `microbenchmark` or `bench` package in R.

```{julia}

using BenchmarkTools

```

### C

We would use the low-level C code as the baseline for copmarison. In Julia, we can easily run compiled C code using the `ccall` function.

```{julia}

using Libdl

C_code = """

#include