---

title: 'Convexity, Duality, and Optimality Conditions (KL Chapter 11, BV Chapter 5)'

subtitle: Biostat/Biomath M257

author: Dr. Hua Zhou @ UCLA

date: today

format:

html:

theme: cosmo

embed-resources: true

number-sections: true

toc: true

toc-depth: 4

toc-location: left

code-fold: false

jupyter:

jupytext:

formats: 'ipynb,qmd'

text_representation:

extension: .qmd

format_name: quarto

format_version: '1.0'

jupytext_version: 1.14.5

kernelspec:

display_name: Julia 1.9.0

language: julia

name: julia-1.9

---

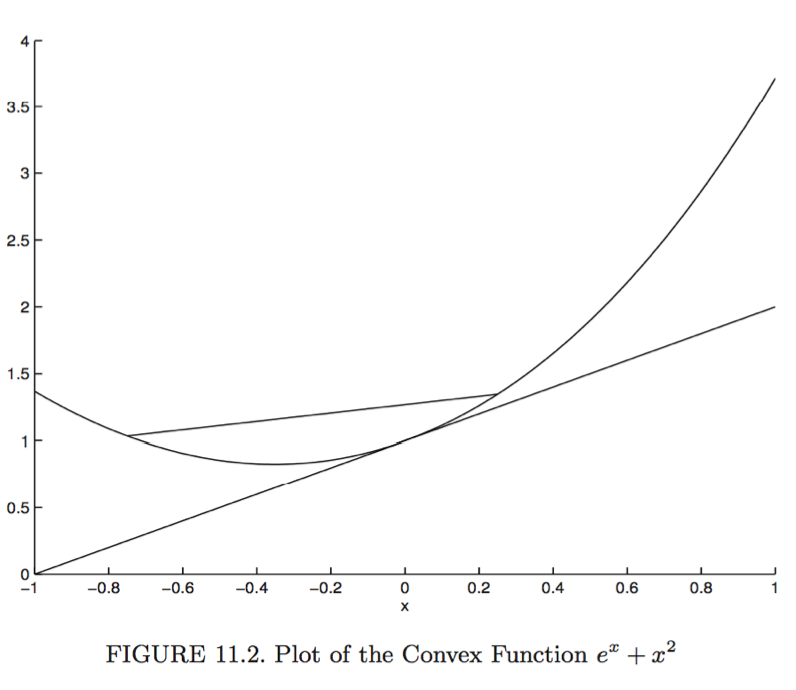

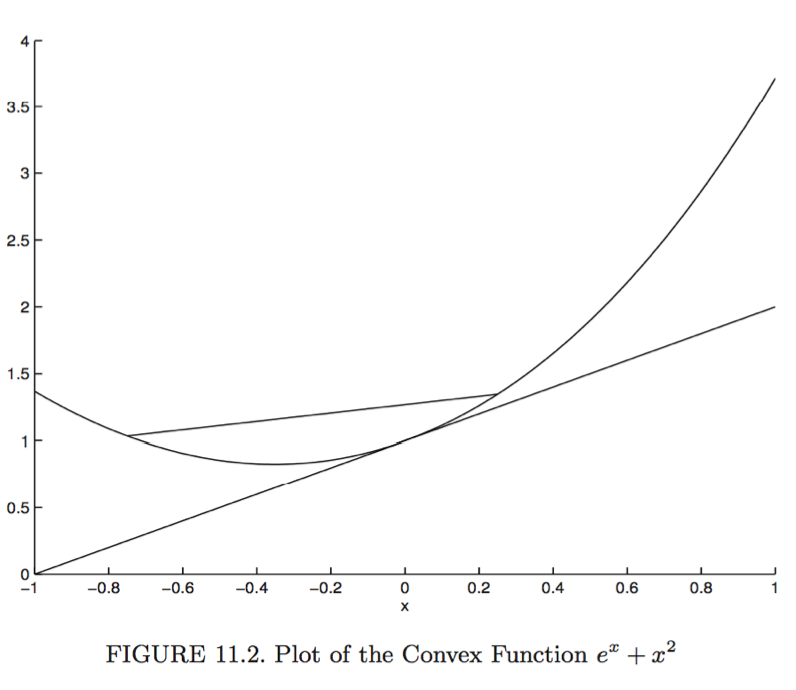

## Convexity

* A function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is **convex** if

1. $\text{dom} f$ is a convex set: $\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and any $\lambda \in (0, 1)$, and

2. $f(\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y}) \le \lambda f(\mathbf{x}) + (1-\lambda) f(\mathbf{y})$, for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda \in (0,1)$.

* $f$ is **strictly convex** if the inequality is strict for all $\mathbf{x} \ne \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda$.

* **Supporting hyperplane inequality**. A differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if

$$

f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y})

$$

for all $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$.

Proof: For the only if part.

$$

f[\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y)] \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

Thus

$$

\frac{f(y + \lambda (x - y)) - f(y)}{\lambda} \le f(x) - f(y).

$$

Taking limit $\lambda \to 0$ yields the supporting hyperplane inequality. For the if part, let $z = \lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y$. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

f(x) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (x - z) \\

f(y) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (y - z).

\end{eqnarray*}

Taking $\lambda \cdot (1) + (1 - \lambda) \cdot (2)$ yields the inequality

$$

f(\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y) \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

* **Second-order condition for convexity**. A twice differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is psd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$. It is strictly convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is pd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.

* Convexity and global optima. Suppose $f$ is a convex function.

1. Any stationary point $\mathbf{y}$, i.e., $\nabla f(\mathbf{y})=\mathbf{0}$, is a global minimum. (Proof: By supporting hyperplane inequality, $f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y}) = f(\mathbf{y})$ for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.)

2. Any local minimum is a global minimum.

3. The set of (global) minima is convex.

4. If $f$ is strictly convex, then the global minimum, if exists, is unique.

* Example: Least squares estimate. $f(\beta) = \frac 12 \| \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \beta \|_2^2$ has Hessian $\nabla^2f = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ which is psd. So $f$ is convex and any stationary point (solution to the normal equation) is a global minimum. When $\mathbf{X}$ is rank deficient, the set of solutions is convex.

* **Jensen's inequality**. If $h$ is convex and $\mathbf{W}$ a random vector taking values in $\text{dom} f$, then

$$

\mathbf{E}[h(\mathbf{W})] \ge h [\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{W})],

$$

provided both expectations exist. For a strictly convex $h$, equality holds if and only if $W = \mathbf{E}(W)$ almost surely.

Proof: Take $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{W}$ and $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{E} (\mathbf{W})$ in the supporting hyperplane inequality.

* **Information inequality**. Let $f$ and $g$ be two densities with respect to a common measure $\mu$ and $f, g>0$ almost everywhere relative to $\mu$. Then

$$

\mathbf{E}_f (\log f) \ge \mathbf{E}_f (\log g),

$$

with equality if and only if $f = g$ almost everywhere on $\mu$.

Proof: Apply Jensen's inequality to the convex function $- \ln(t)$ and random variable $W=g(X)/f(X)$ where $X \sim f$.

Important applications of information inequality: M-estimation, EM algorithm.

## Duality

* Consider optimization problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & h_i(\mathbf{x}) = 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The **Lagrangian** is

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}).

\end{eqnarray*}

The vectors $\lambda = (\lambda_1,\ldots, \lambda_m)^T$ and $\nu = (\nu_1,\ldots,\nu_p)^T$ are called the **Lagrange multiplier vectors** or **dual variables**.

* The **Lagrange dual function** is the minimum value of the Langrangian over $\mathbf{x}$

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \mu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Denote the optimal value of original problem by $p^\star$. For any $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ and any $\nu$, we have

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

Proof: For any feasible point $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}})

\end{eqnarray*}

because the second term is non-positive and the third term is zero. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) \le L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Since each pair $(\lambda, \nu)$ with $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ gives a lower bound to the optimal value $p^\star$. It is natural to ask for the best possible lower bound the Lagrange dual function can provide. This leads to the **Lagrange dual problem**

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{maximize}& g(\lambda, \nu) \\

&\text{subject to}& \lambda \succeq \mathbf{0},

\end{eqnarray*}

which is a convex problem regardless the primal problem is convex or not.

* We denote the optimal value of the Lagrange dual problem by $d^\star$, which satifies the **week duality**

\begin{eqnarray*}

d^\star \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

The difference $p^\star - d^\star$ is called the **optimal duality gap**.

* If the primal problem is convex, that is

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b},

\end{eqnarray*}

with $f_0,\ldots,f_m$ convex, we usually (but not always) have the **strong duality**, i.e., $d^\star = p^\star$.

* The conditions under which strong duality holds are called **constraint qualifications**. A commonly used one is **Slater's condition**: There exists a point in the relative interior of the domain such that

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}) < 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m, \quad \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Such a point is also called **strictly feasible**.

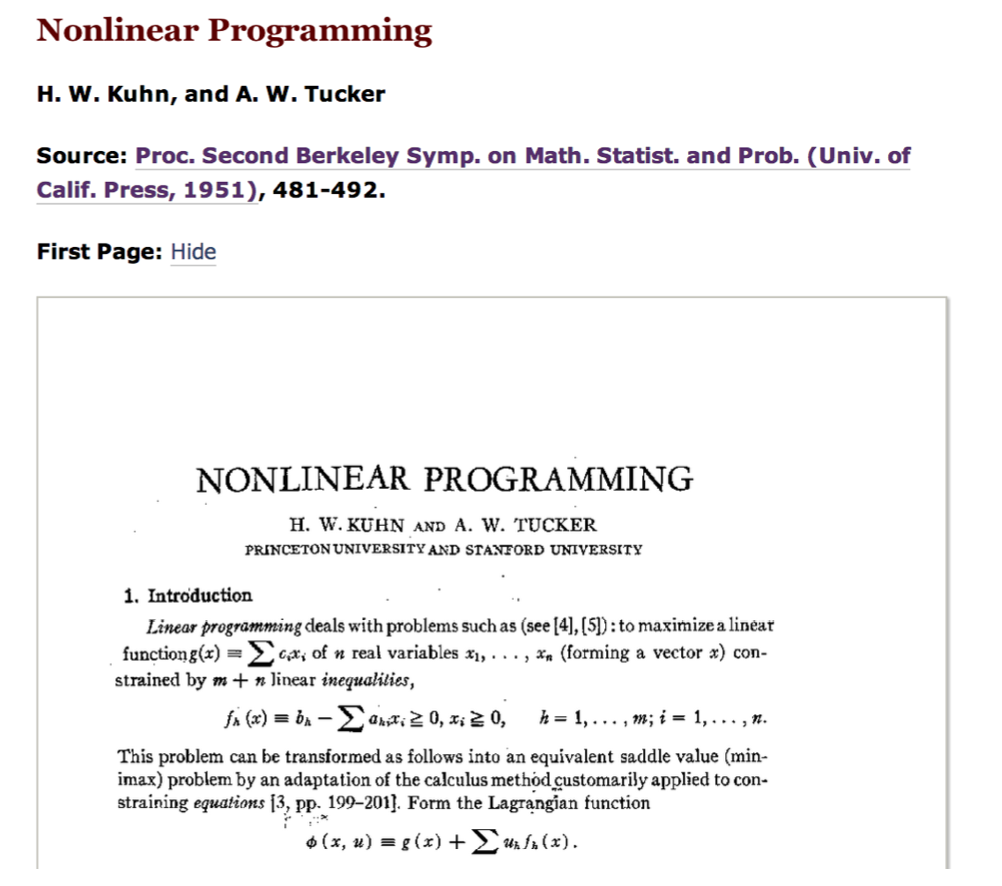

## KKT optimality conditions

KKT is "one of the great triumphs of 20th century applied mathematics" (KL Chapter 11).

* A function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is **convex** if

1. $\text{dom} f$ is a convex set: $\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and any $\lambda \in (0, 1)$, and

2. $f(\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y}) \le \lambda f(\mathbf{x}) + (1-\lambda) f(\mathbf{y})$, for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda \in (0,1)$.

* $f$ is **strictly convex** if the inequality is strict for all $\mathbf{x} \ne \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda$.

* **Supporting hyperplane inequality**. A differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if

$$

f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y})

$$

for all $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$.

Proof: For the only if part.

$$

f[\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y)] \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

Thus

$$

\frac{f(y + \lambda (x - y)) - f(y)}{\lambda} \le f(x) - f(y).

$$

Taking limit $\lambda \to 0$ yields the supporting hyperplane inequality. For the if part, let $z = \lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y$. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

f(x) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (x - z) \\

f(y) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (y - z).

\end{eqnarray*}

Taking $\lambda \cdot (1) + (1 - \lambda) \cdot (2)$ yields the inequality

$$

f(\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y) \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

* **Second-order condition for convexity**. A twice differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is psd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$. It is strictly convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is pd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.

* Convexity and global optima. Suppose $f$ is a convex function.

1. Any stationary point $\mathbf{y}$, i.e., $\nabla f(\mathbf{y})=\mathbf{0}$, is a global minimum. (Proof: By supporting hyperplane inequality, $f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y}) = f(\mathbf{y})$ for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.)

2. Any local minimum is a global minimum.

3. The set of (global) minima is convex.

4. If $f$ is strictly convex, then the global minimum, if exists, is unique.

* Example: Least squares estimate. $f(\beta) = \frac 12 \| \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \beta \|_2^2$ has Hessian $\nabla^2f = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ which is psd. So $f$ is convex and any stationary point (solution to the normal equation) is a global minimum. When $\mathbf{X}$ is rank deficient, the set of solutions is convex.

* **Jensen's inequality**. If $h$ is convex and $\mathbf{W}$ a random vector taking values in $\text{dom} f$, then

$$

\mathbf{E}[h(\mathbf{W})] \ge h [\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{W})],

$$

provided both expectations exist. For a strictly convex $h$, equality holds if and only if $W = \mathbf{E}(W)$ almost surely.

Proof: Take $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{W}$ and $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{E} (\mathbf{W})$ in the supporting hyperplane inequality.

* **Information inequality**. Let $f$ and $g$ be two densities with respect to a common measure $\mu$ and $f, g>0$ almost everywhere relative to $\mu$. Then

$$

\mathbf{E}_f (\log f) \ge \mathbf{E}_f (\log g),

$$

with equality if and only if $f = g$ almost everywhere on $\mu$.

Proof: Apply Jensen's inequality to the convex function $- \ln(t)$ and random variable $W=g(X)/f(X)$ where $X \sim f$.

Important applications of information inequality: M-estimation, EM algorithm.

## Duality

* Consider optimization problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & h_i(\mathbf{x}) = 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The **Lagrangian** is

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}).

\end{eqnarray*}

The vectors $\lambda = (\lambda_1,\ldots, \lambda_m)^T$ and $\nu = (\nu_1,\ldots,\nu_p)^T$ are called the **Lagrange multiplier vectors** or **dual variables**.

* The **Lagrange dual function** is the minimum value of the Langrangian over $\mathbf{x}$

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \mu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Denote the optimal value of original problem by $p^\star$. For any $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ and any $\nu$, we have

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

Proof: For any feasible point $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}})

\end{eqnarray*}

because the second term is non-positive and the third term is zero. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) \le L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Since each pair $(\lambda, \nu)$ with $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ gives a lower bound to the optimal value $p^\star$. It is natural to ask for the best possible lower bound the Lagrange dual function can provide. This leads to the **Lagrange dual problem**

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{maximize}& g(\lambda, \nu) \\

&\text{subject to}& \lambda \succeq \mathbf{0},

\end{eqnarray*}

which is a convex problem regardless the primal problem is convex or not.

* We denote the optimal value of the Lagrange dual problem by $d^\star$, which satifies the **week duality**

\begin{eqnarray*}

d^\star \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

The difference $p^\star - d^\star$ is called the **optimal duality gap**.

* If the primal problem is convex, that is

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b},

\end{eqnarray*}

with $f_0,\ldots,f_m$ convex, we usually (but not always) have the **strong duality**, i.e., $d^\star = p^\star$.

* The conditions under which strong duality holds are called **constraint qualifications**. A commonly used one is **Slater's condition**: There exists a point in the relative interior of the domain such that

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}) < 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m, \quad \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Such a point is also called **strictly feasible**.

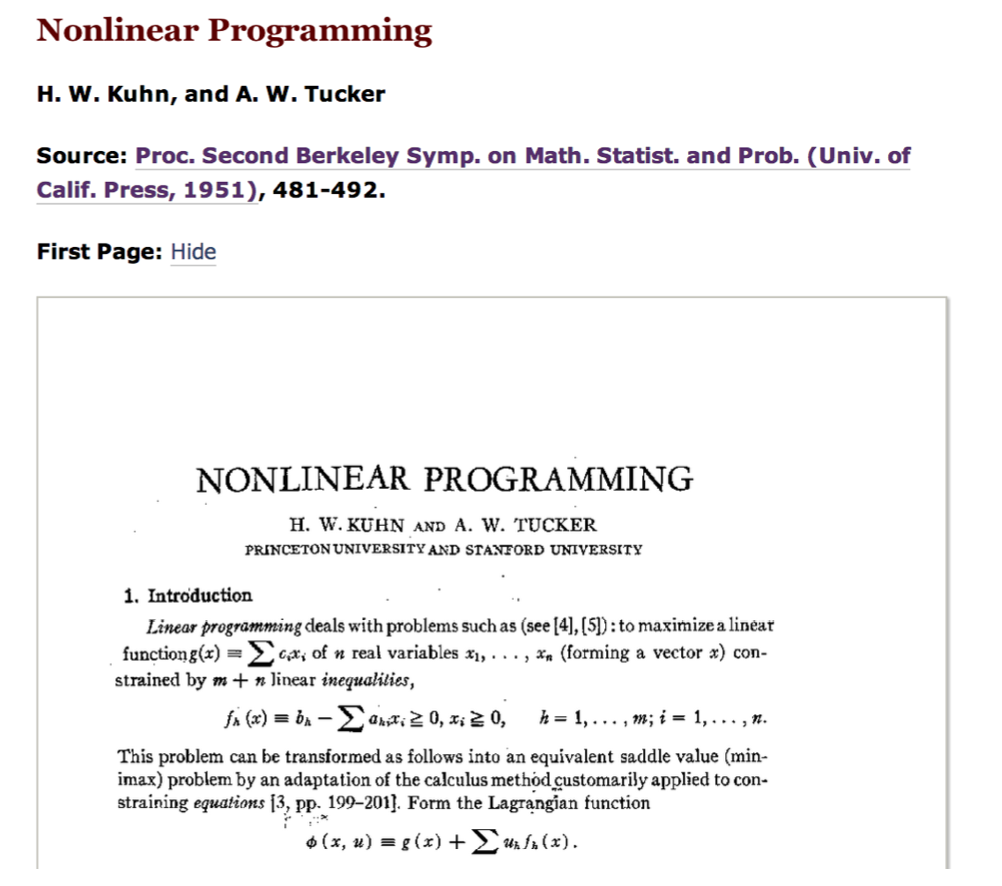

## KKT optimality conditions

KKT is "one of the great triumphs of 20th century applied mathematics" (KL Chapter 11).

### Nonconvex problems

* Assume $f_0,\ldots,f_m,h_1,\ldots,h_p$ are differentiable. Let $\mathbf{x}^\star$ and $(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ be any primal and dual optimal points with zero duality gap, i.e., strong duality holds.

* Since $\mathbf{x}^\star$ minimizes $L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ over $\mathbf{x}$, its gradient vanishes at $\mathbf{x}^\star$, we have the **Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions**

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &\le& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p \\

\lambda_i^\star &\ge& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i=1,\ldots,m \\

\nabla f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star \nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& \mathbf{0}.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The fourth condition (**complementary slackness**) follows from

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& g(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star) \\

&=& \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star).

\end{eqnarray*}

Since $\sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$ and each term is non-positive, we have $\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$, $i=1,\ldots,m$.

* To summarize, for any optimization problem with differentiable objective and constraint functions for which strong duality obtains, any pair of primal and dual optimal points must satisfy the KKT conditions.

### Convex problems

* When the primal problem is convex, the KKT conditions are also sufficient for the points to be primal and dual optimal.

* If $f_i$ are convex and $h_i$ are affine, and $(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ satisfy the KKT conditions, then $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ and $(\tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ are primal and dual optimal, with zero duality gap.

* The KKT conditions play an important role in optimization. Many algorithms for convex optimization are conceived as, or can be interpreted as, methods for solving the KKT conditions.

### Nonconvex problems

* Assume $f_0,\ldots,f_m,h_1,\ldots,h_p$ are differentiable. Let $\mathbf{x}^\star$ and $(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ be any primal and dual optimal points with zero duality gap, i.e., strong duality holds.

* Since $\mathbf{x}^\star$ minimizes $L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ over $\mathbf{x}$, its gradient vanishes at $\mathbf{x}^\star$, we have the **Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions**

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &\le& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p \\

\lambda_i^\star &\ge& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i=1,\ldots,m \\

\nabla f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star \nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& \mathbf{0}.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The fourth condition (**complementary slackness**) follows from

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& g(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star) \\

&=& \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star).

\end{eqnarray*}

Since $\sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$ and each term is non-positive, we have $\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$, $i=1,\ldots,m$.

* To summarize, for any optimization problem with differentiable objective and constraint functions for which strong duality obtains, any pair of primal and dual optimal points must satisfy the KKT conditions.

### Convex problems

* When the primal problem is convex, the KKT conditions are also sufficient for the points to be primal and dual optimal.

* If $f_i$ are convex and $h_i$ are affine, and $(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ satisfy the KKT conditions, then $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ and $(\tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ are primal and dual optimal, with zero duality gap.

* The KKT conditions play an important role in optimization. Many algorithms for convex optimization are conceived as, or can be interpreted as, methods for solving the KKT conditions.

* A function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is **convex** if

1. $\text{dom} f$ is a convex set: $\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and any $\lambda \in (0, 1)$, and

2. $f(\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y}) \le \lambda f(\mathbf{x}) + (1-\lambda) f(\mathbf{y})$, for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda \in (0,1)$.

* $f$ is **strictly convex** if the inequality is strict for all $\mathbf{x} \ne \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda$.

* **Supporting hyperplane inequality**. A differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if

$$

f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y})

$$

for all $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$.

Proof: For the only if part.

$$

f[\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y)] \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

Thus

$$

\frac{f(y + \lambda (x - y)) - f(y)}{\lambda} \le f(x) - f(y).

$$

Taking limit $\lambda \to 0$ yields the supporting hyperplane inequality. For the if part, let $z = \lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y$. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

f(x) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (x - z) \\

f(y) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (y - z).

\end{eqnarray*}

Taking $\lambda \cdot (1) + (1 - \lambda) \cdot (2)$ yields the inequality

$$

f(\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y) \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

* **Second-order condition for convexity**. A twice differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is psd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$. It is strictly convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is pd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.

* Convexity and global optima. Suppose $f$ is a convex function.

1. Any stationary point $\mathbf{y}$, i.e., $\nabla f(\mathbf{y})=\mathbf{0}$, is a global minimum. (Proof: By supporting hyperplane inequality, $f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y}) = f(\mathbf{y})$ for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.)

2. Any local minimum is a global minimum.

3. The set of (global) minima is convex.

4. If $f$ is strictly convex, then the global minimum, if exists, is unique.

* Example: Least squares estimate. $f(\beta) = \frac 12 \| \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \beta \|_2^2$ has Hessian $\nabla^2f = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ which is psd. So $f$ is convex and any stationary point (solution to the normal equation) is a global minimum. When $\mathbf{X}$ is rank deficient, the set of solutions is convex.

* **Jensen's inequality**. If $h$ is convex and $\mathbf{W}$ a random vector taking values in $\text{dom} f$, then

$$

\mathbf{E}[h(\mathbf{W})] \ge h [\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{W})],

$$

provided both expectations exist. For a strictly convex $h$, equality holds if and only if $W = \mathbf{E}(W)$ almost surely.

Proof: Take $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{W}$ and $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{E} (\mathbf{W})$ in the supporting hyperplane inequality.

* **Information inequality**. Let $f$ and $g$ be two densities with respect to a common measure $\mu$ and $f, g>0$ almost everywhere relative to $\mu$. Then

$$

\mathbf{E}_f (\log f) \ge \mathbf{E}_f (\log g),

$$

with equality if and only if $f = g$ almost everywhere on $\mu$.

Proof: Apply Jensen's inequality to the convex function $- \ln(t)$ and random variable $W=g(X)/f(X)$ where $X \sim f$.

Important applications of information inequality: M-estimation, EM algorithm.

## Duality

* Consider optimization problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & h_i(\mathbf{x}) = 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The **Lagrangian** is

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}).

\end{eqnarray*}

The vectors $\lambda = (\lambda_1,\ldots, \lambda_m)^T$ and $\nu = (\nu_1,\ldots,\nu_p)^T$ are called the **Lagrange multiplier vectors** or **dual variables**.

* The **Lagrange dual function** is the minimum value of the Langrangian over $\mathbf{x}$

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \mu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Denote the optimal value of original problem by $p^\star$. For any $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ and any $\nu$, we have

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

Proof: For any feasible point $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}})

\end{eqnarray*}

because the second term is non-positive and the third term is zero. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) \le L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Since each pair $(\lambda, \nu)$ with $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ gives a lower bound to the optimal value $p^\star$. It is natural to ask for the best possible lower bound the Lagrange dual function can provide. This leads to the **Lagrange dual problem**

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{maximize}& g(\lambda, \nu) \\

&\text{subject to}& \lambda \succeq \mathbf{0},

\end{eqnarray*}

which is a convex problem regardless the primal problem is convex or not.

* We denote the optimal value of the Lagrange dual problem by $d^\star$, which satifies the **week duality**

\begin{eqnarray*}

d^\star \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

The difference $p^\star - d^\star$ is called the **optimal duality gap**.

* If the primal problem is convex, that is

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b},

\end{eqnarray*}

with $f_0,\ldots,f_m$ convex, we usually (but not always) have the **strong duality**, i.e., $d^\star = p^\star$.

* The conditions under which strong duality holds are called **constraint qualifications**. A commonly used one is **Slater's condition**: There exists a point in the relative interior of the domain such that

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}) < 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m, \quad \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Such a point is also called **strictly feasible**.

## KKT optimality conditions

KKT is "one of the great triumphs of 20th century applied mathematics" (KL Chapter 11).

* A function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \mapsto \mathbb{R}$ is **convex** if

1. $\text{dom} f$ is a convex set: $\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and any $\lambda \in (0, 1)$, and

2. $f(\lambda \mathbf{x} + (1-\lambda) \mathbf{y}) \le \lambda f(\mathbf{x}) + (1-\lambda) f(\mathbf{y})$, for all $\mathbf{x},\mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda \in (0,1)$.

* $f$ is **strictly convex** if the inequality is strict for all $\mathbf{x} \ne \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$ and $\lambda$.

* **Supporting hyperplane inequality**. A differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if

$$

f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y})

$$

for all $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \text{dom} f$.

Proof: For the only if part.

$$

f[\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y)] \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

Thus

$$

\frac{f(y + \lambda (x - y)) - f(y)}{\lambda} \le f(x) - f(y).

$$

Taking limit $\lambda \to 0$ yields the supporting hyperplane inequality. For the if part, let $z = \lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y$. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

f(x) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (x - z) \\

f(y) - f(z) &\ge& f'(z) (y - z).

\end{eqnarray*}

Taking $\lambda \cdot (1) + (1 - \lambda) \cdot (2)$ yields the inequality

$$

f(\lambda x + (1 - \lambda) y) \le \lambda f(x) + (1 - \lambda) f(y).

$$

* **Second-order condition for convexity**. A twice differentiable function $f$ is convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is psd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$. It is strictly convex if and only if $\nabla^2f(\mathbf{x})$ is pd for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.

* Convexity and global optima. Suppose $f$ is a convex function.

1. Any stationary point $\mathbf{y}$, i.e., $\nabla f(\mathbf{y})=\mathbf{0}$, is a global minimum. (Proof: By supporting hyperplane inequality, $f(\mathbf{x}) \ge f(\mathbf{y}) + \nabla f(\mathbf{y})^T (\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y}) = f(\mathbf{y})$ for all $\mathbf{x} \in \text{dom} f$.)

2. Any local minimum is a global minimum.

3. The set of (global) minima is convex.

4. If $f$ is strictly convex, then the global minimum, if exists, is unique.

* Example: Least squares estimate. $f(\beta) = \frac 12 \| \mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X} \beta \|_2^2$ has Hessian $\nabla^2f = \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X}$ which is psd. So $f$ is convex and any stationary point (solution to the normal equation) is a global minimum. When $\mathbf{X}$ is rank deficient, the set of solutions is convex.

* **Jensen's inequality**. If $h$ is convex and $\mathbf{W}$ a random vector taking values in $\text{dom} f$, then

$$

\mathbf{E}[h(\mathbf{W})] \ge h [\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{W})],

$$

provided both expectations exist. For a strictly convex $h$, equality holds if and only if $W = \mathbf{E}(W)$ almost surely.

Proof: Take $\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{W}$ and $\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{E} (\mathbf{W})$ in the supporting hyperplane inequality.

* **Information inequality**. Let $f$ and $g$ be two densities with respect to a common measure $\mu$ and $f, g>0$ almost everywhere relative to $\mu$. Then

$$

\mathbf{E}_f (\log f) \ge \mathbf{E}_f (\log g),

$$

with equality if and only if $f = g$ almost everywhere on $\mu$.

Proof: Apply Jensen's inequality to the convex function $- \ln(t)$ and random variable $W=g(X)/f(X)$ where $X \sim f$.

Important applications of information inequality: M-estimation, EM algorithm.

## Duality

* Consider optimization problem

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & h_i(\mathbf{x}) = 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The **Lagrangian** is

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}).

\end{eqnarray*}

The vectors $\lambda = (\lambda_1,\ldots, \lambda_m)^T$ and $\nu = (\nu_1,\ldots,\nu_p)^T$ are called the **Lagrange multiplier vectors** or **dual variables**.

* The **Lagrange dual function** is the minimum value of the Langrangian over $\mathbf{x}$

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \mu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Denote the optimal value of original problem by $p^\star$. For any $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ and any $\nu$, we have

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

Proof: For any feasible point $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$,

\begin{eqnarray*}

L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) = f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i f_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i h_i(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}})

\end{eqnarray*}

because the second term is non-positive and the third term is zero. Then

\begin{eqnarray*}

g(\lambda, \nu) = \inf_{\mathbf{x}} L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda, \nu) \le L(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \lambda, \nu) \le f_0(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}).

\end{eqnarray*}

* Since each pair $(\lambda, \nu)$ with $\lambda \succeq \mathbf{0}$ gives a lower bound to the optimal value $p^\star$. It is natural to ask for the best possible lower bound the Lagrange dual function can provide. This leads to the **Lagrange dual problem**

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{maximize}& g(\lambda, \nu) \\

&\text{subject to}& \lambda \succeq \mathbf{0},

\end{eqnarray*}

which is a convex problem regardless the primal problem is convex or not.

* We denote the optimal value of the Lagrange dual problem by $d^\star$, which satifies the **week duality**

\begin{eqnarray*}

d^\star \le p^\star.

\end{eqnarray*}

The difference $p^\star - d^\star$ is called the **optimal duality gap**.

* If the primal problem is convex, that is

\begin{eqnarray*}

&\text{minimize}& f_0(\mathbf{x}) \\

&\text{subject to}& f_i(\mathbf{x}) \le 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

& & \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b},

\end{eqnarray*}

with $f_0,\ldots,f_m$ convex, we usually (but not always) have the **strong duality**, i.e., $d^\star = p^\star$.

* The conditions under which strong duality holds are called **constraint qualifications**. A commonly used one is **Slater's condition**: There exists a point in the relative interior of the domain such that

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}) < 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m, \quad \mathbf{A} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}.

\end{eqnarray*}

Such a point is also called **strictly feasible**.

## KKT optimality conditions

KKT is "one of the great triumphs of 20th century applied mathematics" (KL Chapter 11).

### Nonconvex problems

* Assume $f_0,\ldots,f_m,h_1,\ldots,h_p$ are differentiable. Let $\mathbf{x}^\star$ and $(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ be any primal and dual optimal points with zero duality gap, i.e., strong duality holds.

* Since $\mathbf{x}^\star$ minimizes $L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ over $\mathbf{x}$, its gradient vanishes at $\mathbf{x}^\star$, we have the **Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions**

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &\le& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p \\

\lambda_i^\star &\ge& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i=1,\ldots,m \\

\nabla f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star \nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& \mathbf{0}.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The fourth condition (**complementary slackness**) follows from

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& g(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star) \\

&=& \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star).

\end{eqnarray*}

Since $\sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$ and each term is non-positive, we have $\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$, $i=1,\ldots,m$.

* To summarize, for any optimization problem with differentiable objective and constraint functions for which strong duality obtains, any pair of primal and dual optimal points must satisfy the KKT conditions.

### Convex problems

* When the primal problem is convex, the KKT conditions are also sufficient for the points to be primal and dual optimal.

* If $f_i$ are convex and $h_i$ are affine, and $(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ satisfy the KKT conditions, then $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ and $(\tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ are primal and dual optimal, with zero duality gap.

* The KKT conditions play an important role in optimization. Many algorithms for convex optimization are conceived as, or can be interpreted as, methods for solving the KKT conditions.

### Nonconvex problems

* Assume $f_0,\ldots,f_m,h_1,\ldots,h_p$ are differentiable. Let $\mathbf{x}^\star$ and $(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ be any primal and dual optimal points with zero duality gap, i.e., strong duality holds.

* Since $\mathbf{x}^\star$ minimizes $L(\mathbf{x}, \lambda^\star, \nu^\star)$ over $\mathbf{x}$, its gradient vanishes at $\mathbf{x}^\star$, we have the **Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions**

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &\le& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,p \\

\lambda_i^\star &\ge& 0, \quad i = 1,\ldots,m \\

\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& 0, \quad i=1,\ldots,m \\

\nabla f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star \nabla h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& \mathbf{0}.

\end{eqnarray*}

* The fourth condition (**complementary slackness**) follows from

\begin{eqnarray*}

f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) &=& g(\lambda^\star, \nu^\star) \\

&=& \inf_{\mathbf{x}} \left( f_0(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}) \right) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) + \sum_{i=1}^p \nu_i^\star h_i(\mathbf{x}^\star) \\

&\le& f_0(\mathbf{x}^\star).

\end{eqnarray*}

Since $\sum_{i=1}^m \lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$ and each term is non-positive, we have $\lambda_i^\star f_i(\mathbf{x}^\star)=0$, $i=1,\ldots,m$.

* To summarize, for any optimization problem with differentiable objective and constraint functions for which strong duality obtains, any pair of primal and dual optimal points must satisfy the KKT conditions.

### Convex problems

* When the primal problem is convex, the KKT conditions are also sufficient for the points to be primal and dual optimal.

* If $f_i$ are convex and $h_i$ are affine, and $(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}, \tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ satisfy the KKT conditions, then $\tilde{\mathbf{x}}$ and $(\tilde \lambda, \tilde \nu)$ are primal and dual optimal, with zero duality gap.

* The KKT conditions play an important role in optimization. Many algorithms for convex optimization are conceived as, or can be interpreted as, methods for solving the KKT conditions.