---

execute:

echo: true

message: false

warning: false

fig-format: "svg"

format:

revealjs:

highlight-style: a11y-dark

reference-location: margin

theme: lecture_styles.scss

controls: true

controls-tutorial: true

slide-number: true

code-link: true

chalkboard: true

incremental: false

smaller: true

preview-links: true

code-line-numbers: true

history: false

progress: true

link-external-icon: true

code-annotations: hover

pointer:

color: "#b18eb1"

revealjs-plugins:

- pointer

---

```{r}

#| echo: false

#| cache: false

require(downlit)

require(xml2)

require(tidyverse)

library(gapminder)

#options(width = 90)

```

## {#title-slide data-menu-title="Manipulating and Summarizing Data" background="#1e4655" background-image="../../images/csss-logo.png" background-position="center top 5%" background-size="50%"}

[Manipulating and Summarizing Data]{.custom-title}

[CS&SS 508 • Lecture 4]{.custom-subtitle}

[{{< var lectures.four >}}]{.custom-subtitle2}

[Victoria Sass]{.custom-subtitle3}

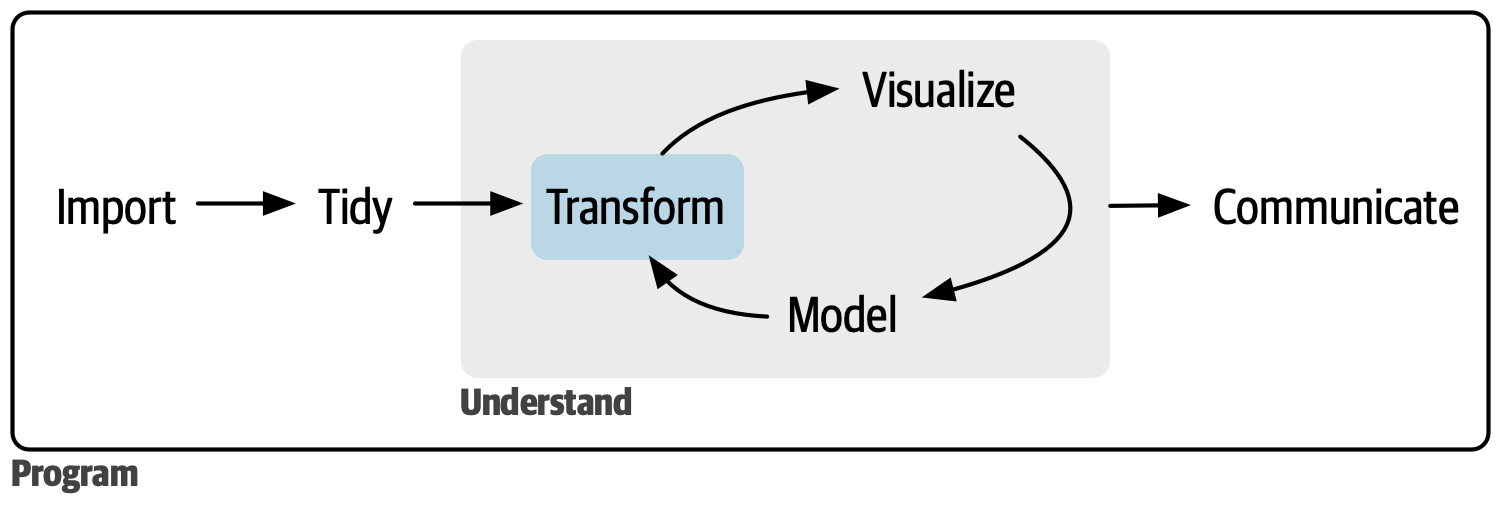

# Roadmap{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

---

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

### Last time, we learned:

* Best Practices

* Code Style

* Workflow

* Reproducible Research

* Indexing vectors & dataframes in Base `R`

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

### Today, we will cover:

* Types of Data

* Logical Operators

* Subsetting data

* Modifying data

* Summarizing data

* Merging data

:::

:::

::::

. . .

{fig-align="center"}

## Death to Spreadsheets

Tools like *Excel* or *Google Sheets* let you manipulate spreadsheets using functions.

::: {.incremental}

* Spreadsheets are *not reproducible*: It's hard to know how someone changed the raw data!

* It's hard to catch mistakes when you use spreadsheets^[Don't be the next sad Research Assistant who makes headlines with an Excel error! ([Reinhart & Rogoff, 2010](http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-04-18/faq-reinhart-rogoff-and-the-excel-error-that-changed-history))].

:::

. . .

Today, we'll use `R` to manipulate data more *transparently* and *reproducibly*.

## How is data stored in `R`?

Under the hood, R stores different types of data in different ways.

. . .

* e.g., R knows that `4.0` is a number, and that `"Vic"` is not a number.

. . .

So what exactly are the common data types, and how do we know what R is doing?

. . .

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

* Logicals (`logical`)

* Factors (`factor`)

* Date/Date-time (`Date`, `POSIXct`, `POSIXt`)

* Numbers (`integer`, `double`)

* Missing Values (`NA`, `NaN`, `Inf`)

* Character Strings (`character`)

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

* `c(FALSE, TRUE, TRUE)`

* `factor(c("red", "blue"))`

* `as_Date(c("2018-10-04"))`

* `c(1, 10*3, 4, -3.14)`

* `c(NA, NA, NA, NaN, NaN, NA)`

* `c("red", "blue", "blue")`

:::

:::

::::

# Logical Operators{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Booleans

The simplest data type is a Boolean, or binary, variable: `TRUE` or `FALSE`^[or `NA`].

. . .

More often than not our data don't actually have a variable with this data type, but they are definitely created and evaluated in the data manipulation and summarizing process.

. . .

Logical operators refer to base functions which allow us to **test if a condition** is present between two objects.

. . .

For example, we may test

+ Is A equal to B?

+ Is A greater than B?

+ Is A within B?

. . .

Naturally, these types of expressions produce a binary outcome of `T` or `F` which enables us to transform our data in a variety of ways!

## Logical Operators in `R`

#### Comparing objects

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="19%"}

::: {.fragment}

* `==`:

* `!=`:

* `>`, `>=`, `<`, `<=`:

* `%in%`:

:::

:::

::: {.column width="81%"}

::: {.fragment}

* is equal to^[Note: there are TWO equal signs here!]

* not equal to

* less than, less than or equal to, etc.

* used when checking if equal to one of several values

:::

:::

::::

:::{.fragment}

#### Combining comparisons

:::

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="19%"}

::: {.fragment}

* `&`:

* `|`:

* `!`:

* `xor()`:

:::

:::

::: {.column width="81%"}

::: {.fragment .bullet-spacing}

* **both** conditions need to hold (AND)\

* **at least one** condition needs to hold (OR)\

* **inverts** a logical condition (`TRUE` becomes `FALSE`, vice versa)\

* **exclusive OR** (i.e. x or y but NOT both)

:::

:::

::::

::: {.aside}

[You may also see `&&` and `||` but they are what's known as short-circuiting operators and are not to be used in `dplyr` functions (used for programming not data manipulation); they'll only ever return a single `TRUE` or `FALSE`.]{.fragment}

:::

## Unexpected Behavior

Be careful using `==` with numbers:

. . .

```{r}

(x <- c(1 / 49 * 49, sqrt(2) ^ 2)) # <1>

```

1. Wrapping an entire object assignment in parentheses simultaneously defines the object and shows you what it represents.

```{r}

x == c(1, 2) # <2>

print(x, digits = 16) # <3>

```

2. Computers store numbers with a fixed number of decimal places so there’s no way to *precisely* represent decimals.

3. `dplyr::near()` is a useful alternative which ignores small differences.

. . .

Similarly mysterious, missing values (`NA`) represent the unknown. Almost anything conditional involving `NA`s will also be unknown:

```{r}

NA > 5

10 == NA

NA == NA # <4>

```

4. The logic here: if you have one unknown and a second unknown, you don't actually know if they equal one another!

. . .

This is the reason we use `is.na()` to check for missingness.

```{r}

is.na(c(NA, 5))

```

## Examples of Logical Operators

Let's create two objects, `A` and `B`

```{r}

A <- c(5, 10, 15)

B <- c(5, 15, 25)

```

. . .

Comparisons:

```{r}

A == B

A > B

A %in% B # <1>

```

1. Will return a vector the length of `A` that is `TRUE` whenever a value in `A` is anywhere in `B`.

**Note**: You CAN use `%in%` to search for `NA`s.

. . .

Combinations:

```{r}

A > 5 & A <= B

B < 10 | B > 20 # <2>

!(A == 10)

```

2. Be sure not to cut corners (i.e. writing

`B < 10 | > 20`). The code won't technically error but it won't evaluate the way you expect it to. Read more about the confusing logic behind this [here](https://r4ds.hadley.nz/logicals#sec-order-operations-boolean). In essence the truncated second part of this conditional statement (> 20) will evaluate to `TRUE` since any numeric that isn't `0` for a logical operator is coerced to `TRUE`. Therefore this statement will actually always evaluate to `TRUE` and will return all elements of `B` instead of the ones that meet your specified condition.

## Logical Summaries

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="19%"}

::: {.fragment}

* `any()`:

* `all()`:

:::

:::

::: {.column width="81%"}

::: {.fragment}

* the equivalent of `|`; it’ll return `TRUE` if there are any `TRUE`’s in x

* the equivalent of `&`; it’ll return `TRUE` only if all values of x are `TRUE`’s

:::

:::

::::

. . .

\

```{r}

C <- c(5, 10, NA, 10, 20, NA)

any(C <= 10)

```

. . .

```{r}

all(C <= 20) # <1>

```

1. Like other summary functions, they'll return `NA` if there are any missing values present and it's `FALSE`.

. . .

```{r}

all(C <= 20, na.rm = TRUE) # <2>

```

2. Use `na.rm = TRUE` to remove `NA`s prior to evaluation.

. . .

```{r}

mean(C, na.rm = TRUE) # <3>

```

3. When you evaluate a logical vector numerically, `TRUE` = 1 and `FALSE` = 0. This makes `sum()` and `mean()` useful when summarizing logical functions (sum gives number of `TRUE`s and mean gives the proportion).

## Conditional transformations

**`if_else()`**

If you want to use one value when a condition is `TRUE` and another value when it’s `FALSE`.

. . .

```{r}

#| eval: false

if_else(condition = "A logical vector", # <1>

true = "Output when condition is true", # <1>

false = "Output when condition is false") # <1>

```

1. All of these arguments are required.

. . .

```{r}

x <- c(-3:3, NA)

if_else(x > 0, "+ve", "-ve", "???") # <2>

```

2. There’s an optional fourth argument, `missing`, which will be used if the input is `NA`.

. . .

**`case_when()`**

A very useful extension of `if_else()` for multiple conditions^[Note that if multiple conditions match in `case_when()`, only the first will be used.

].

. . .

```{r}

case_when(

x == 0 ~ "0",

x < 0 ~ "-ve",

x > 0 ~ "+ve",

is.na(x) ~ "???" # <3>

) # <4>

```

3. Use `.default` if you want to create a “default”/catch all value.

4. Both functions require compatible types: i.e. numerical and logical, strings and factors, dates and datetimes, `NA` and everything.

# {data-menu-title="`dplyr`" background-image="images/dplyr.png" background-size="contain" background-position="center" .section-title background-color="#1e4655"}

## `dplyr`

Today, we'll use tools from the `dplyr` package to manipulate data!

* Like `ggplot2`, `dplyr` is part of the *Tidyverse*, and included in the `tidyverse` package.

```{r}

library(tidyverse)

```

. . .

To demonstrate data transformations we're going to use the `nycflights13` dataset, which you'll need to download and load into `R`

```{r}

library(nycflights13) # <1>

```

1. Run `install.packages("nycflights13")` in console first.

. . .

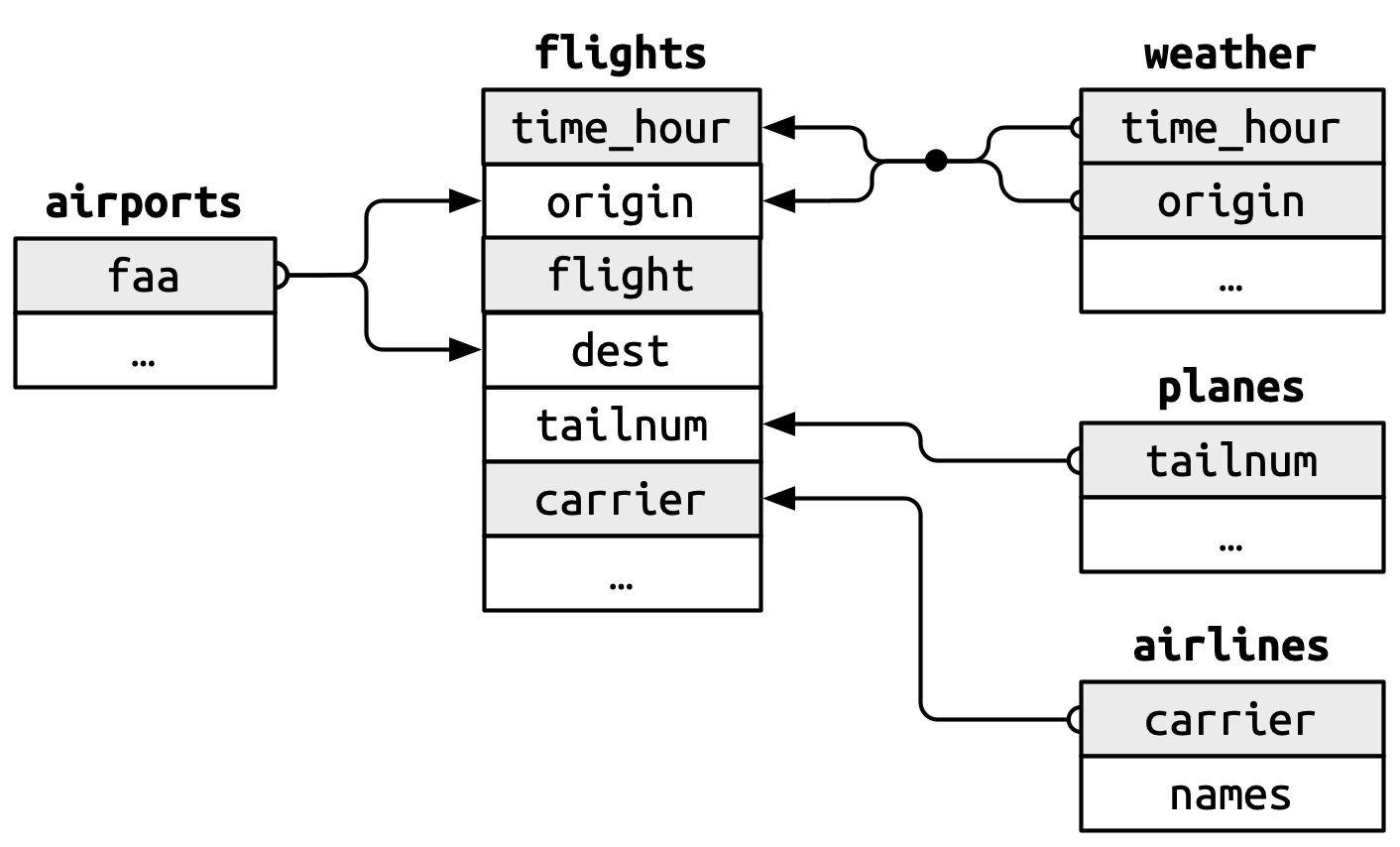

`nycflights13` includes five data frames^[Note these are separate data frames, each needing to be loaded separately. When loading a package containing datasets, you can define those data (i.e. explicitly add them to your working environment) by calling `data()` on their name.]:, some of which contain missing data (`NA`):

```{r}

#| eval: false

data(flights) # <2>

data(airlines) # <3>

data(airports) # <4>

data(planes) # <5>

data(weather) # <6>

```

2. flights leaving JFK, LGA, or EWR in 2013

3. airline abbreviations

4. airport metadata

5. airplane metadata

6. hourly weather data for JFK, LGA, and EWR

## `dplyr` Basics

All `dplyr` functions have the following in common:

::: {.incremental}

1. The first argument is always a data frame.

2. The subsequent arguments typically describe which columns to operate on, using the variable names (without quotes).

3. The output is always a new data frame.

:::

. . .

Each function operates either on rows, columns, groups, or entire tables.

. . .

To save the transformations you've made to a data frame you'll need to save the output to a new object.

# Subsetting data{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Subset Rows: `filter()`

We often get *big* datasets, and we only want some of the entries. We can subset rows using `filter()`.

. . .

```{r}

delay_2hr <- flights |>

filter(dep_delay > 120) # <1>

delay_2hr # <2>

```

1. Here's where all your new knowledge about logical operators comes in handy! Make sure to use `==` not `=` to test the logical condition.

2. Now, `delay_2hr` is an object in our environment which contains rows corresponding to flights that experienced at least a 2 hour delay.

## Subset Columns: `select()`

What if we want to keep every observation, but only use certain variables? Use `select()`!

. . .

We can select columns by name:

```{r}

flights |>

select(year, month, day) # <1>

```

1. You can use a `-` before a variable name or a vector of variables to drop them from the data (i.e.

`select(-c(year, month, day))`).

## Subset Columns: `select()`

What if we want to keep every observation, but only use certain variables? Use `select()`!

We can select columns between variables (inclusive):

```{r}

flights |>

select(year:day) # <1>

```

1. Add a `!` before `year` and you'll drop this group of variables from the data.

## Subset Columns: `select()`

What if we want to keep every observation, but only use certain variables? Use `select()`!

We can select columns based on a condition:

```{r}

flights |>

select(where(is.character)) # <1>

```

1. There are a number of helper functions you can use with `select()` including `starts_with()`, `ends_with()`, `contains()` and `num_range()`. Read more about these and more [here](https://tidyselect.r-lib.org/reference/index.html).

## Finding Unique Rows: `distinct()`

You may want to find the unique combinations of variables in a dataset. Use `distinct()`

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

distinct(origin, dest) # <1>

```

1. Find all unique origin and destination pairs.

## `distinct()` drops variables!

By default, `distinct()` drops unused variables. If you don't want to drop them, add the argument `.keep_all = TRUE`:

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

distinct(origin, dest, .keep_all = TRUE) # <1>

```

1. It’s not a coincidence that all of these distinct flights are on January 1: `distinct()` will find the first occurrence of a unique row in the dataset and discard the rest. Use `count()` if you're looking for the number of occurrences.

## Count Unique Rows: `count()`

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

count(origin, dest, sort = TRUE) # <1>

```

1. `sort = TRUE` arranges them in descending order of number of occurrences.

# Modifying data{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Sorting Data by Rows: `arrange()`

Sometimes it's useful to sort rows in your data, in ascending (low to high) or descending (high to low) order. We do that with `arrange()`.

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

arrange(year, month, day, dep_time) # <1>

```

1. If you provide more than one column name, each additional column will be used to break ties in the values of preceding columns.

## Sorting Data by Rows: `arrange()`

To sort in descending order, using `desc()` within `arrange()`

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

arrange(desc(dep_delay))

```

## Rename Variables: `rename()`

You may receive data with unintuitive variable names. Change them using `rename()`.

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

rename(tail_num = tailnum) # <1>

```

1. `rename(new_name = old_name)` is the format. Reminder to use `janitor::clean_names()` if you want to automate this process for a lot of variables.

. . .

::: {.callout-caution icon=false}

## {{< fa exclamation-triangle >}} Variable Syntax

I recommend **against** using spaces in a name! It makes things *really hard* sometimes!!

:::

## Create New Columns: `mutate()`

You can add new columns to a data frame using `mutate()`.

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

mutate(

gain = dep_delay - arr_delay,

speed = distance / air_time * 60,

.before = 1 # <1>

)

```

1. By default, `mutate()` adds new columns on the right hand side of your dataset, which makes it difficult to see if anything happened. You can use the `.before` argument to specify which numeric index (or variable name) to move the newly created variable to. `.after` is an alternative argument for this.

## Specifying Variables to Keep: `mutate()`

You can specify which columns to keep with the `.keep` argument:

```{r}

flights |>

mutate(

gain = dep_delay - arr_delay,

hours = air_time / 60,

gain_per_hour = gain / hours,

.keep = "used" # <1>

)

```

1. `"used"` retains only the variables used to create the new variables, which is useful for checking your work. Other options include: `"all"` (default, returns all columns), `"unused"` (columns not used to create new columns) and `"none"` (only grouping variables and columns created by mutate are retained).

## Move Variables Around: `relocate()`

You might want to collect related variables together or move important variables to the front. Use `relocate()`!

```{r}

flights |>

relocate(time_hour, air_time) # <1>

```

1. By default `relocate()` moves variables to the front but you can also specify where to put them using the `.before` and `.after` arguments, just like in `mutate()`.

# Summarizing data{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Grouping Data: `group_by()`

If you want to analyze your data by specific groupings, use `group_by()`:

```{r}

flights |>

group_by(month) # <1>

```

1. `group_by()` doesn’t change the data but you’ll notice that the output indicates that it is “grouped by” month `(Groups: month [12])`. This means subsequent operations will now work “by month”.

## Summarizing Data: `summarize()`

**`summarize()`** calculates summaries of variables in your data:

::: {.incremental}

* Count the number of rows

* Calculate the mean

* Calculate the sum

* Find the minimum or maximum value

:::

. . .

You can use any function inside `summarize()` that aggregates *multiple values* into a *single value* (like `sd()`, `mean()`, or `max()`).

## `summarize()` Example

Let's see what this looks like in our flights dataset:

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

summarize(

avg_delay = mean(dep_delay) # <1>

)

```

1. The `NA` produced here is a result of calling `mean` on `dep_delay`. Any summarizing function will return `NA` if **any** of the values are `NA`. We can set `na.rm = TRUE` to change this behavior.

## `summarize()` Example

Let's see what this looks like in our flights dataset:

```{r}

flights |>

summarize(

avg_delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)

)

```

## Summarizing Data by Groups

What if we want to summarize data by our groups? Use `group_by()` **and** `summarize()`

. . .

```{r}

flights |>

group_by(month) |>

summarize(

delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)

)

```

. . .

Because we did `group_by()` *with* `month`, *then* used `summarize()`, we get **one row per value of `month`**!

## Summarizing Data by Groups

You can create any number of summaries in a single call to summarize().

```{r}

flights |>

group_by(month) |>

summarize(

delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE),

n = n() # <1>

)

```

1. `n()` returns the number of rows in each group.

## Grouping by Multiple Variables {{< fa scroll >}} {.scrollable}

```{r}

daily <- flights |>

group_by(year, month, day)

daily

```

. . .

::: {.callout-tip icon=false}

## {{< fa info-circle >}} Summary & Grouping Behavior

When you summarize a tibble grouped by more than one variable, each summary peels off the last group. You can change the default behavior by setting the `.groups` argument to a different value, e.g., `"drop"` to drop all grouping or `"keep"` to preserve the same groups. The default is `"drop_last"` if all groups have 1 row and `keep` otherwise (it's recommended to use `reframe()` if this is the case, which is a more general version of `summarize()` that allows for an arbitrary number of rows per group and drops all grouping variables after execution).

:::

## Remove Grouping: `ungroup()`

```{r}

daily |>

ungroup()

```

## Newer Alternative for Grouping: `.by`

```{r}

flights |>

summarize(

delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE),

n = n(),

.by = month # <1>

)

```

1. `.by` works with all verbs and has the advantage that you don’t need to use the `.groups` argument to suppress the grouping message or `ungroup()` when you’re done.

## Select Specific Rows Per Group: `slice_*`

There are five handy functions that allow you extract specific rows within each group:

::: {.incremental}

* `df |> slice_head(n = 1)` takes the first row from each group.

* `df |> slice_tail(n = 1)` takes the last row in each group.

* `df |> slice_min(x, n = 1)` takes the row with the smallest value of column x.

* `df |> slice_max(x, n = 1)` takes the row with the largest value of column x.

* `df |> slice_sample(n = 1)` takes one random row.

:::

. . .

Let's find the flights that are most delayed upon arrival at each destination.

## Select Specific Rows Per Group: `slice_*`

```{r}

flights |>

group_by(dest) |>

slice_max(arr_delay, n = 1) |> # <1>

relocate(dest, arr_delay)

```

1. You can vary `n` to select more than one row, or instead of `n`, you can use `prop` to select a proportion (between 0 and 1) of the rows in each group.

::: {.aside}

[There are 105 groups but 108 rows! Why? `slice_min()` and `slice_max()` keep tied values so `n = 1` means "give us all rows with the highest value." If you want exactly one row per group you can set `with_ties = FALSE`.]{.fragment}

:::

# Lab{.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Manipulating Data

1. Create a new object that contains the following from `gapminder`^[Using the `gapminder` package]

i. observations from China, India, and United States after 1980, *and*

ii. variables corresponding to country, year, population, and life expectancy.

1. How many rows and columns does the object contain?

1. Sort the rows by `year` (ascending order) and `population` (descending order) and save that over (i.e. overwrite) the object created for answer 1. Print the first 6 rows.

1. Create a new variable that contains population in billions.

1. By year, calculate the total population (in billions) across these three countries

1. In `ggplot`, create a line plot showing life expectancy over time by country. Make the plot visually appealing!

## Answers

Question 1:

```{r}

subset_gapminder <- gapminder |>

filter(country %in% c("China","India","United States"), year > 1980 ) |> # <1>

select(country, year, pop, lifeExp)

subset_gapminder

```

1. You can specify multiple conditional conditions in `filter()` by separating them with commas

## Answers

Question 2:

```{r}

# Option 1

c(nrow(subset_gapminder), ncol(subset_gapminder))

# Option 2

glimpse(subset_gapminder)

# Option 3

dim(subset_gapminder)

```

## Answers

Question 3:

```{r}

subset_gapminder <- subset_gapminder |>

arrange(year, desc(pop)) # <1>

```

1. The default for `arrange()` is to sort in ascending order

. . .

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

```{r}

subset_gapminder |> head(6)

```

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

```{r}

print(subset_gapminder[1:6, ])

```

:::

::::

## Answers

Question 4:

```{r}

subset_gapminder <- subset_gapminder |>

mutate(pop_billions = pop/1000000000)

subset_gapminder

```

## Answers

Question 5:

::: {.panel-tabset}

### Classic syntax

```{r}

subset_gapminder |>

group_by(year) |>

summarize(TotalPop_Billions = sum(pop_billions))

```

### New syntax (dplyr 1.1.0)

```{r}

subset_gapminder |>

summarize(TotalPop_Billions = sum(pop_billions),

.by = year) # <1>

```

1. This new syntax allows for per-operation grouping which means it is only active within a single verb at a time (as opposed to being applied to the entire tibble until `ungroup()` is called). Learn more about this new feature [here](https://www.tidyverse.org/blog/2023/02/dplyr-1-1-0-per-operation-grouping/))

:::

## Answers

Question 6:

::: {.panel-tabset}

### Code

```{r}

#| eval: false

library(ggplot2)

library(ggthemes)

library(geomtextpath)

ggplot(subset_gapminder,

aes(year, lifeExp, color = country)) + # <1>

geom_point() + # <2>

geom_textpath(aes(label = country), # <3>

show.legend = FALSE) + # <4>

labs(title = "Life Expectancy (1982-2007)","China, India, and United States", # <5>

x = "Year", # <5>

y = "Life Expectancy (years)") + # <5>

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007)) + # <6>

ylim(c(50, 80)) + # <7>

theme_tufte(base_size = 20) # <8>

```

1. Map `year` to the x-axis, `lifeExp` to the y-axis, and `country` to color

2. Add points geom to plot data

3. Use `geom_textpath()` from the `geomtextpath` package to make nice labelled lines (specify mapping of `country` to the label)

4. Remove legend (redundant with labelled lines)

5. Add descriptive plot title and axis labels

6. Limit x-axis ticks and labels to only six specified years

7. Zoom in on y-axis range to limit whitespace

8. Use nice theme from `ggthemes` package and increase text size throughout plot

### Plot

```{r}

#| fig-height: 6

#| fig-width: 12

#| fig-align: center

#| echo: false

library(ggplot2)

library(ggthemes)

library(geomtextpath)

ggplot(subset_gapminder, aes(year, lifeExp, color = country)) +

theme_tufte(base_size = 20) +

geom_point() +

geom_textpath(aes(label = country), show.legend = FALSE) +

xlab("Year") +

ylab("Life Expectancy (years)") +

ggtitle("Life Expectancy (1982-2007)","China, India, and United States") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, 2002, 2007), minor_breaks = c()) +

ylim(c(50, 80)) + scale_color_discrete(name = "Country") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

```

:::

# Merging Data {.section-title background-color="#99a486"}

## Why Merge Data?

In practice, we often collect data from different sources. To analyze the data, we usually must first combine (merge) them.

. . .

For example, imagine you would like to study county-level patterns with respect to age and grocery spending. However, you can only find,

* County level age data from the US Census, and

* County level grocery spending data from the US Department of Agriculture

. . .

Merge the data!!

. . .

To do this we'll be using the various **join** functions from the `dplyr` package.

## Joining in Concept

We need to think about the following when we want to merge data frames A and B:

::: {.fragment}

* Which rows are we keeping from each data frame?

:::

::: {.fragment}

* Which columns are we keeping from each data frame?

:::

::: {.fragment .fade-in}

::: {.fragment .highlight-red}

* Which variables determine whether rows match?

:::

:::

## Keys

Keys are the way that two datasets are connected to one another. The two types of keys are:

::: {.incremental}

1. **Primary**: a variable or set of variables that uniquely identifies each observation.

i) When more than one variable makes up the primary key it's called a **compound key**

2. **Foreign**: a variable (or set of variables) that corresponds to a primary key in another table.

:::

---

### Primary Keys

[Let's look at our data to gain a better sense of what this all means.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

::: {.panel-tabset}

### `airlines`

[`airlines` records two pieces of data about each airline: its carrier code and its full name. You can identify an airline with its two letter carrier code, making `carrier` the primary key.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

```{r}

glimpse(airlines) # <1>

```

1. Use `glimpse` on any dataset to see a transposed version of the data, making it possible to see all available column names, types, and a preview of as many values will fit on your current screen.

### `airports`

[`airports` records data about each airport. You can identify each airport by its three letter airport code, making `faa` the primary key.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

```{r}

glimpse(airports)

```

### `planes`

[`planes` records data about each plane. You can identify a plane by its tail number, making `tailnum` the primary key.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

```{r}

glimpse(planes)

```

### `weather`

[`weather` records data about the weather at the origin airports. You can identify each observation by the combination of location and time, making `origin` and `time_hour` the compound primary key.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

```{r}

glimpse(weather)

```

### `flights`

[`flights` has three variables (`time_hour`, `flight`, `carrier`) that uniquely identify an observation. More significantly, however, it contains **foreign keys** that correspond to the primary keys of the other datasets.]{style="font-size: 80%;"}

```{r}

glimpse(flights)

```

:::

---

### Foreign Keys

{fig-align="center"}

::: {.incremental}

* `flights$origin` --> `airports$faa`

* `flights$dest` --> `airports$faa`

* `flights$origin`-`flights$time_hour` --> `weather$origin`-`weather$time_hour`.

* `flights$tailnum` --> `planes$tailnum`

* `flights$carrier` --> `airlines$carrier`

:::

## Checking Keys

A nice feature of these data are that the primary and foreign keys have the same name and almost every variable name used across multiple tables has the same meaning.^[With the exception of `year`: it means year of departure in `flights` and year of manufacture in `planes`. ] This isn't always the case!^[We'll cover how to handle this shortly.]

. . .

It is good practice to make sure your primary keys actually uniquely identify an observation and that they don't have any missing values.

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

planes |>

count(tailnum) |> # <1>

filter(n > 1) # <1>

```

1. If your primary keys uniquely identify each observation you'll get an empty tibble in return.

. . .

```{r}

planes |>

filter(is.na(tailnum)) # <2>

```

2. If none of your primary keys are missing you'll get an empty tibble in return here too.

## Surrogate Keys

Sometimes you'll want to create an index of your observations to serve as a surrogate key because the compound primary key is not particularly easy to reference.

. . .

For example, our `flights` dataset has three variables that uniquely identify each observation: `time_hour`, `carrier`, `flight`.

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

flights2 <- flights |>

mutate(id = row_number(), .before = 1) # <1>

flights2

```

1. `row_number()` simply specifies the row number of the data frame.

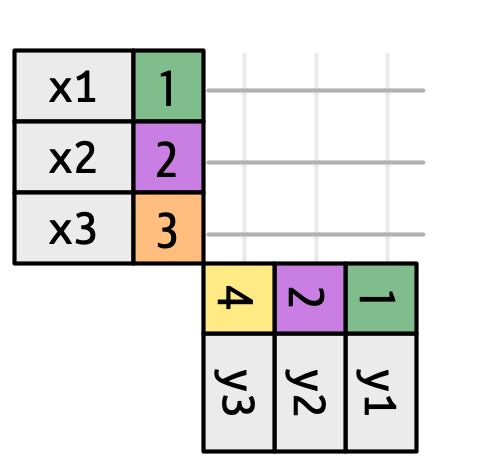

## Basic (Equi-) Joins

All join functions have the same basic interface: they take a **pair** of data frames and return **one** data frame.

. . .

The order of the rows and columns is primarily going to be determined by the first data frame.

. . .

`dplyr` has two types of joins: *mutating* and *filtering.*

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

#### Mutating Joins

Add new variables to one data frame from matching observations from another data frame.

* `left_join()`

* `right_join()`

* `inner_join()`

* `full_join()`

:::

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

#### Filtering Joins

Filter observations from one data frame based on whether or not they match an observation in another data frame.

* `semi_join()`

* `anti-join()`

:::

:::

::::

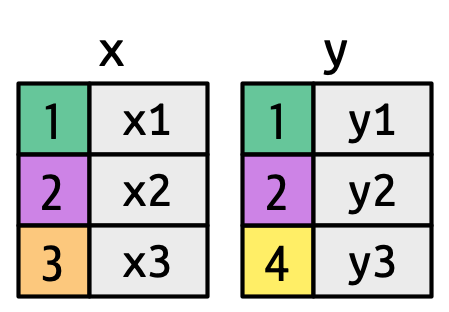

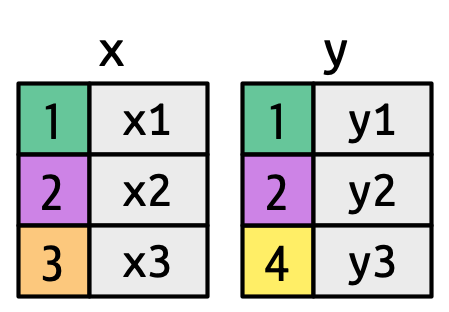

## `Mutating Joins`

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

:::

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

:::

:::

::::

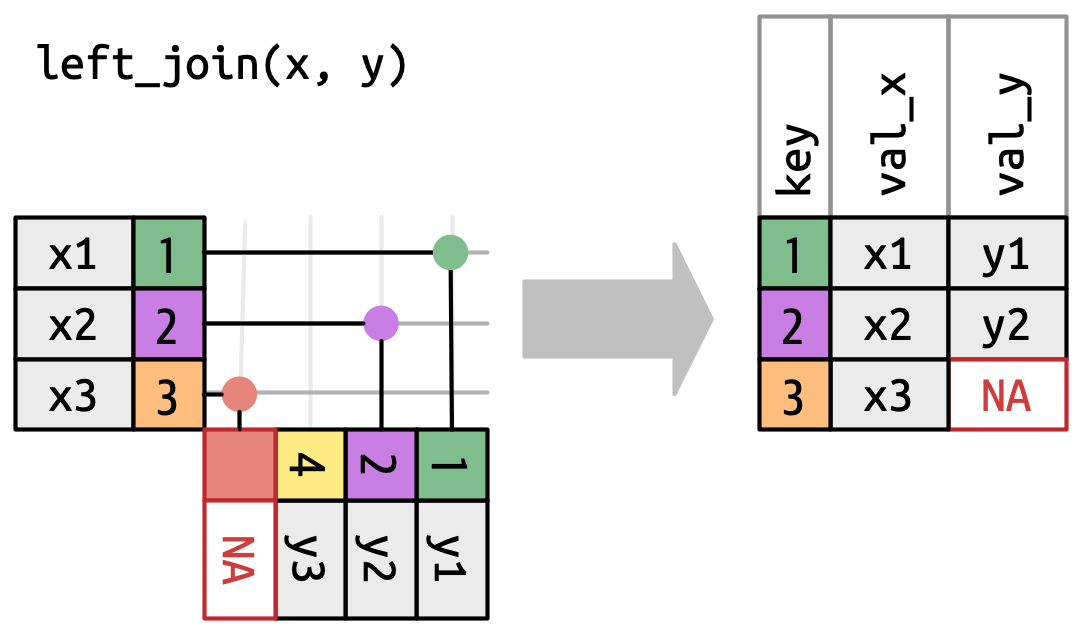

## `left_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

::: {.r-stack}

::: {.incremental}

[The most common type of join]{.fragment .fade-in-then-out fragment-index=1 .absolute top=0 right=0}

[Appends columns from `y` to `x` by the rows in `x` \

(`NA` added if there is nothing from `y`)]{.fragment fragment-index=2 .absolute top=0 right=0}

[**Natural join**: when all variables that appear in both datasets are used as the join key. \

\

*If the `join_by()` argument is not specified, `left_join()` will automatically join by all columns that have names and values in common.*]{.fragment fragment-index=3 .absolute bottom=-225 right=0 style="font-size: 80%;" width="500" height="400"}

:::

:::

## `left_join` in `nycflights13`

```{r}

flights2 <- flights |>

select(year, time_hour, origin, dest, tailnum, carrier)

```

With only the pertinent variables from the `flights` dataset, we can see how a `left_join` works with the `airlines` dataset.

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

#| message: true

flights2 |>

left_join(y = airlines) # <1>

```

1. The `airlines` dataset has variables `carrier` and `name`

## Different variable meanings

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

#| message: true

flights2 |>

left_join(planes) # <1>

```

1. The `planes` dataset has variables `tailnum`, `year`, `type`, `manufacturer`, `model`, `engines`, `seats`, `speed`, and `engine`

\

[When we try to do this, however, we get a bunch of `NA`s. Why?]{.fragment .fade-in-then-out}

::: aside

[*Join is trying to use tailnum and year as a compound key.* While both datasets have `year` as a variable, they mean **different** things. Therefore, we need to be explicit here about what to join by. ]{.fragment}

:::

## Different variable meanings

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

flights2 |>

left_join(y = planes, by = join_by(tailnum)) # <1>

```

1. `join_by(tailnum)` is short for `join_by(tailnum == tailnum)` making these types of basic joins equi joins.

::: aside

[When you have the same variable name but they mean different things you can specify a particular suffix with the `suffix` argument in the `_join` function. By default the suffix will be `.x` for the variable from the first dataset and `.y` for the variable from the second dataset.]{.fragment}

:::

## Different variable names

If you have keys that have the same meaning (values) but are named different things in their respective datasets you'd also specify that with `join_by()`

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

flights2 |>

left_join(airports, join_by(dest == faa)) # <1>

```

1. `by = c("dest" = "faa")` was the former syntax for this and you still might see that in older code. You can specify multiple `join_by`s by simply separating the conditional statements with `,` (i.e. `join_by(x == y, a == b)`).

::: aside

[This will match `dest` to `faa` for the join and then drop `faa`.]{.fragment}

:::

## Different variable names

You can request `dplyr` to keep both keys with `keep = TRUE` argument.

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

flights2 |>

left_join(airports, join_by(dest == faa), keep = TRUE)

```

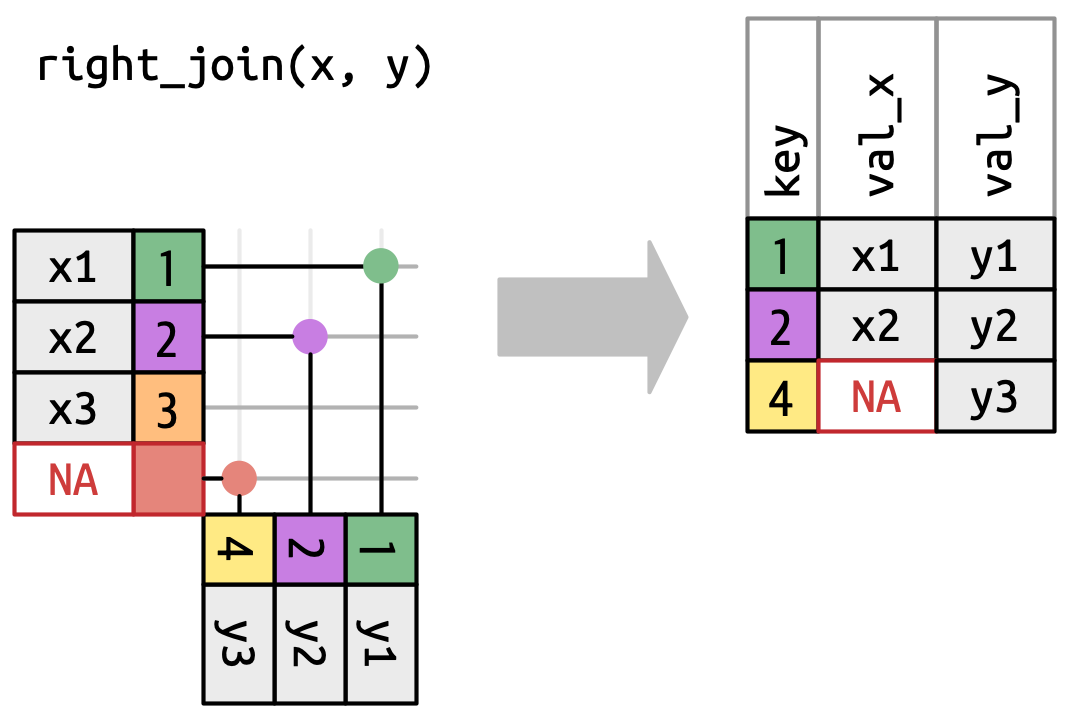

## `right_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

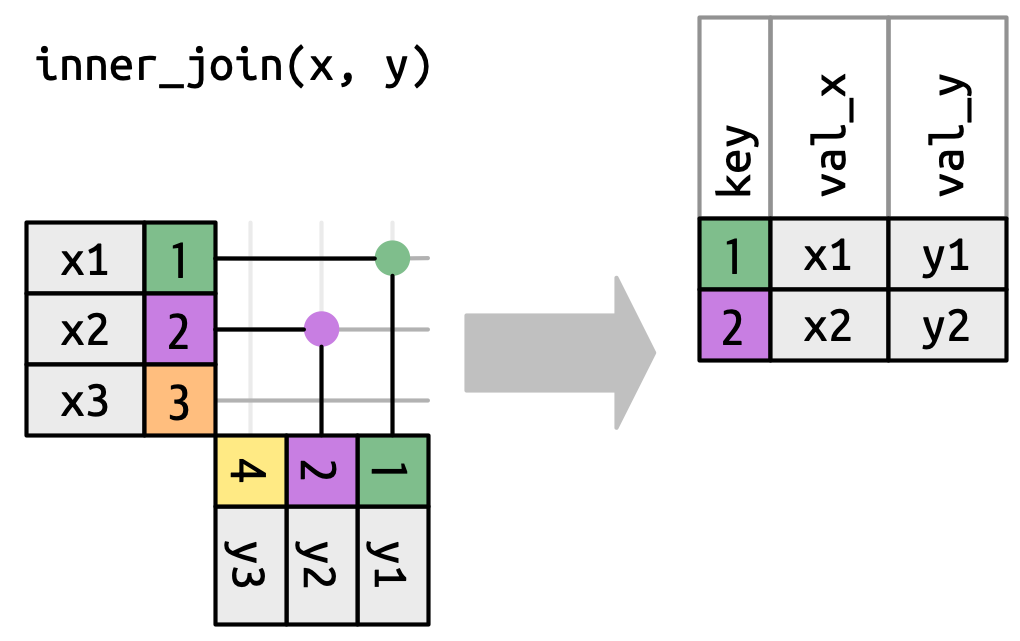

## `inner_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

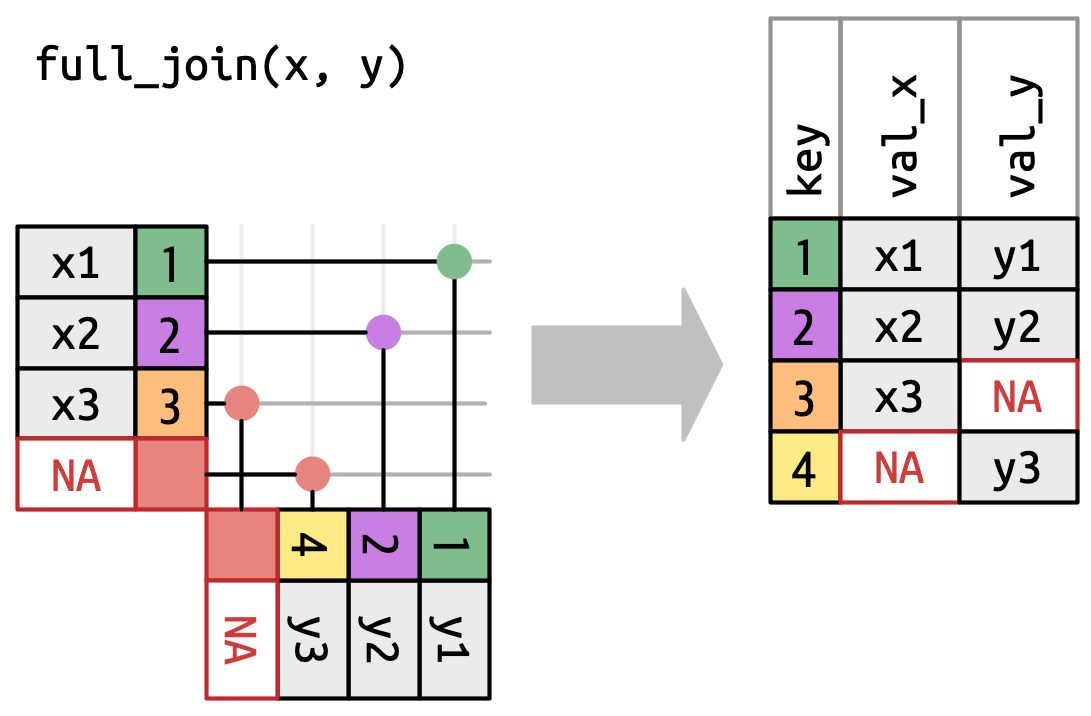

## `full_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

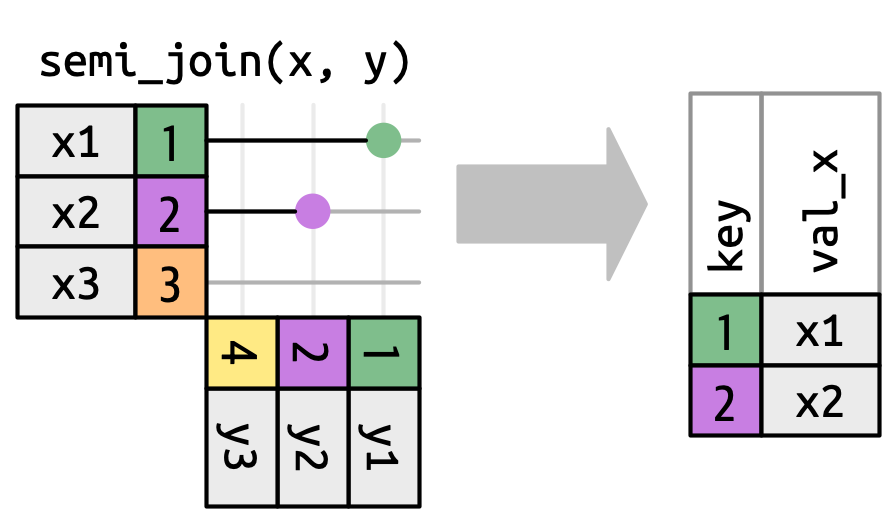

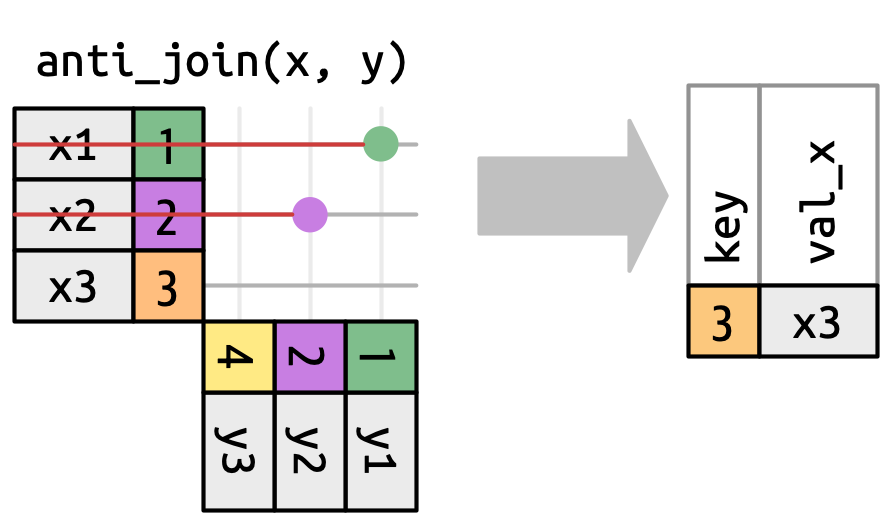

## `Filtering Joins`

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

:::

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

::: {.fragment}

:::

:::

::::

## `semi_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

## `semi_join()` in `nycflights13`

We could use a semi-join to filter the airports dataset to show just the origin airports.

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

airports |>

semi_join(flights2, join_by(faa == origin))

```

## `anti_join()`

{fig-align="center"}

## `anti_join()` in `nycflights13`

We can find rows that are missing from airports by looking for flights that don’t have a matching destination airport.

. . .

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

airports |>

anti_join(flights2, join_by(faa == origin))

```

::: aside

[This type of join is useful for finding missing values that are implicit in the data (i.e. `NA`s that don't show up in the data but only exist as an absence.)]{.fragment}

:::

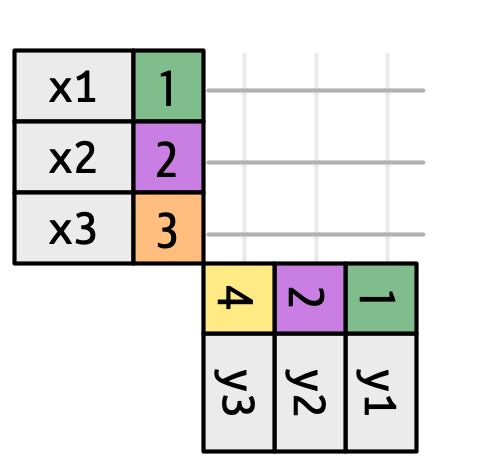

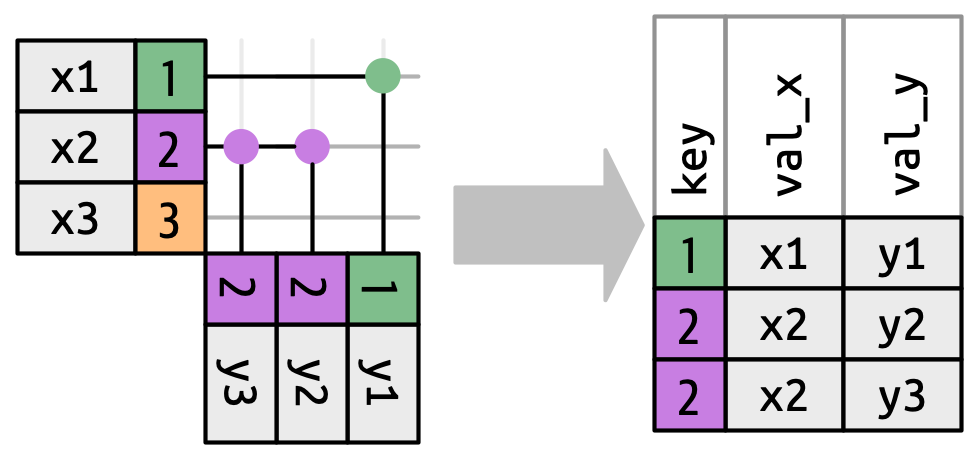

## More Than One Match

{fig-align="center"}

. . .

There are three possible outcomes for a row in x:

::: {.incremental}

* If it doesn’t match anything, it’s dropped.

* If it matches 1 row in `y`, it’s preserved.

* If it matches more than 1 row in ` y`, it’s duplicated once for each match.

:::

. . .

What happens if we match on more than one row?

## More Than One Match

```{r}

#| output-location: fragment

#| warning: true

df1 <- tibble(key = c(1, 2, 2), val_x = c("x1", "x2", "x3"))

df2 <- tibble(key = c(1, 2, 2), val_y = c("y1", "y2", "y3"))

df1 |>

inner_join(df2, join_by(key))

```

::: {.aside}

::: {.r-stack}

[If you are doing this deliberately, you can set `relationship = "many-to-many"`, as the warning suggests.]{.fragment .fade-in-then-out}

[Note: Given their nature, *filtering* joins never duplicate rows like mutating joins do. They will only ever return a subset of the datasets.]{.fragment}

:::

:::

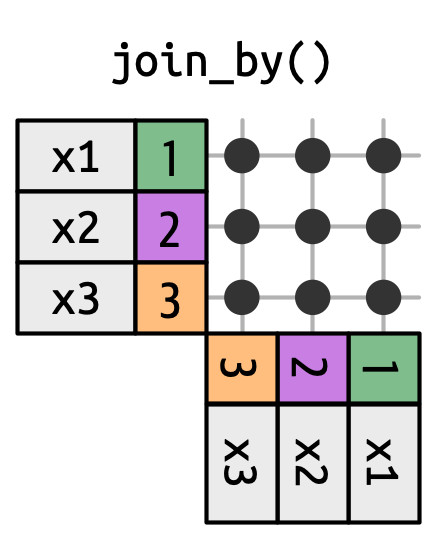

## Non-Equi Joins

The joins we've discussed thus far have all been equi-joins, where the rows match if the x key equals the y key. But you can also specify other types of relationships.

. . .

`dplyr` has four different types of non-equi joins:

. . .

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

* **Cross joins** match every pair of rows.

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

{width=25% .absolute top=150 right=150}

:::

::::

::: aside

[Cross joins, aka self-joins, are useful when generating permutations (e.g. creating every possible combination of values). This comes in handy when creating datasets of predicted probabilities for plotting in ggplot.]{.fragment}

:::

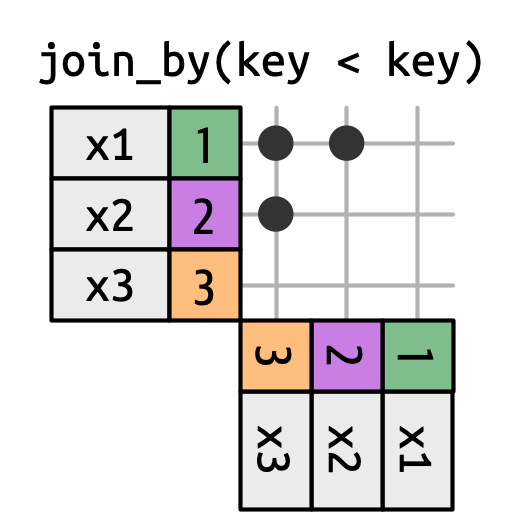

## Non-Equi Joins

The joins we've discussed thus far have all been equi-joins, where the rows match if the x key equals the y key. But you can also specify other types of relationships.

`dplyr` has four different types of non-equi joins:

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

* **Cross joins** match every pair of rows.

* **Inequality joins** use <, <=, >, and >= instead of ==.

* **Overlap joins** are a special type of inequality join designed to work with ranges^[Overlap joins provide three helpers that use inequality joins to make it easier to work with intervals: `between()`, `within()`, `overlaps()`. Read more about their functionality and specifications [here](https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/reference/join_by.html?q=within#overlap-joins).].

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

{width=30% .absolute top=158 right=120}

:::

::::

::: aside

Inequality joins can be used to restrict the cross join so that instead of generating all permutations, we generate all combinations.

:::

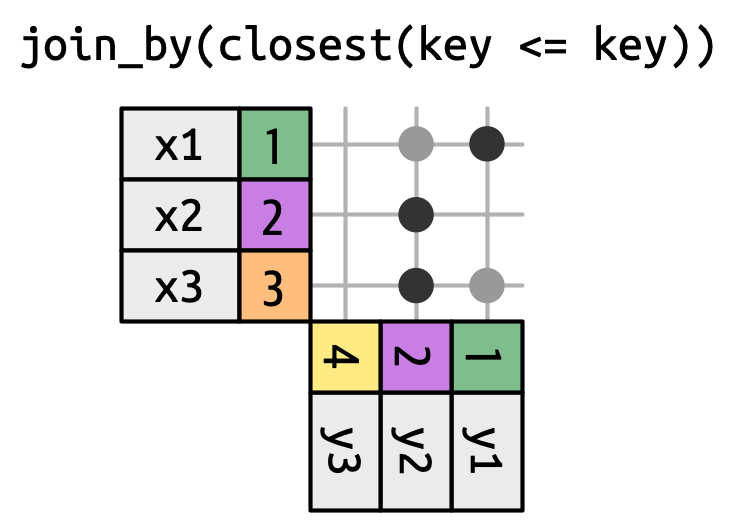

## Non-Equi Joins

The joins we've discussed thus far have all been equi-joins, where the rows match if the x key equals the y key. But you can also specify other types of relationships.

`dplyr` has four different types of non-equi joins:

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="50%"}

* **Cross joins** match every pair of rows.

* **Inequality joins** use <, <=, >, and >= instead of ==.

* **Overlap joins** are a special type of inequality join designed to work with ranges.

* **Rolling joins** are similar to inequality joins but only find the closest match.

:::

::: {.column width="50%"}

{width=42% .absolute top=155 right=35}

:::

::::

::: aside

Rolling joins are a special type of inequality join where instead of getting every row that satisfies the inequality, you get just the closest row. You can turn any inequality join into a rolling join by adding closest().

:::

# Homework{.section-title background-color="#1e4655"}

## {data-menu-title="Homework 4" background-iframe="https://vsass.github.io/CSSS508/Homework/HW4/homework4.html" background-interactive=TRUE}