As Youth Coordinator at Billerica Access Television, one of the primary focuses of my job is to develop curriculum and media projects for the kids who join BATV’s Youth Programs. Several of my programs are collaborative efforts with the local schools, which creates a more academic atmosphere. For these after school enrichment programs, I tend to structure the projects and curriculum more than I would with some of my other programs. The typical structure of my enrichment programs is that I explain a media literacy topic, give the students in the group a chance to discuss the topic, and then present a media-related project relating to the topic. One of my favorite units is my “fake news” video project, which I have done for the past two years. I’ve geared this project towards 4th-5th graders as well as 6th-8th graders due to the demographics of my enrichment groups.

Kicking Off The Project

I begin the unit by having students describe where people get their news and collaboratively creating a list. In the past year, I noticed there has been an uptick in kids listing off specific websites and apps rather than broad categories of news sources like television or radio, which I’ve found to be interesting. After that, we talk about what makes a news source “good” and create another list. We discuss things like bias, objectivity, deceptive headlines, balanced reporting, and diverse viewpoints. In some groups (particularly the elementary schoolers), we’ve dived into discussing what bias means and why news might be bias (ex. a news source might have political leanings, may not want to be critical of advertisers, etc.) We then wrap up our conversation by talking about “hard news” and “soft news” as well as “click bait.” I then give students time to share their experiences and opinions regarding news sources. One of my most memorable stories was from a young girl who challenged a misleading article her aunt posted on Facebook, which turned out to be a fake story.

The Search for the Fake Headline

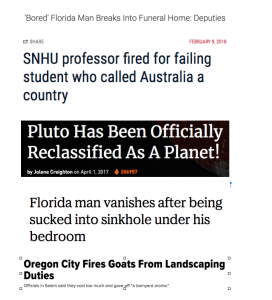

Find the fake news headline!

After our discussion, I give students a sheet of paper with several headlines. They must work as a group (usually groups of two or three) to determine which headline is not from a legitimate news article. They must also explain their reasoning. Most of the time, they select the headline based on if there is a questionable time stamp near the headline, font styles that don’t “match up” with what they’ve seen in other headlines in the past, and also cite the ridiculousness of the article headline (ex. “How can goats get fired?!”) Students typically are unable to accurately guess which headline is real, which makes for an interesting follow-up discussion about misleading headlines and how news sources often cover “ridiculous” news articles in order to draw an audience in and receive more page views. We also touch on how ad revenue plays a role in news coverage (i.e. the more people you get to check out a page –> the more people you get clicking ads on sidebars –> the more money the news source gets). This conversation in particular brings up a lot of anecdotes and discussions among students, especially surrounding targeted advertisements based on web searches, etc.

The Final Video Project

After this activity, I introduce the video project to students. In groups of three, students must come up with their own fake news headline. They must go through the planning process of brainstorming an idea, writing a basic synopsis, writing a script, storyboarding, filming, and oftentimes editing their piece. I encourage creativity throughout this process and have gotten some very elaborate news stories including the following:

- A Horse Becomes President of the United States

- A Kindergartner Puts Cockroaches in Trump Tower (You Won’t Believe What Happens Next!)

- Amber Quits BATV In Dramatic Departure

- Lack of Funding For State Park Leads To Pop Tart Forest Fire

The students really take this idea and run with it. They also troubleshoot issues that arise in the production process and work on their critical thinking skills. It’s made for a very popular unit among the enrichment programs I’ve worked with.

Design Justices Principles

In terms of the Design Justice Network principles, I feel that I’ve tried to make this project do a good job of meeting several of the principles without even realizing it. For instance, I place great importance on centering the voices of those directly impacted by the design process by giving space for students to not only discuss news-related issues, but also to take ownership over the development of their video. I’ve done this through taking feedback about whether the project is engaging to them, improvements that can be made to it, allowing them space to talk about their thoughts on what they’re being presented with and assisting students to allow their full vision for the video to come to life (i.e. When a group needed me to dramatically speed away in my car after “quitting”, I had no qualms about helping out!). Similarly, I’ve made an effort to view the project through viewing change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process. By having discussions with students about news sources, a mutual learning environment is created. I’ve learned a great deal about what kids deem to be relevant news, how they perceive news systems, and how they feel they might be able to change things. Students learn how to work together to develop this news project as well as learning from concrete examples of misleading news articles. I’ve also altered the project in some cases to make it accessible to the different needs of students I work with (i.e. explaining the project in a different way, working more closely with groups that struggle with the production process, etc.)

As for what I’m lacking with this project, I think I can work on look for what is already working at the community level. Librarians and teachers in the school system are already doing lessons related to how to do research (i.e. look at sources of articles, look at diverse articles, etc.) as well as basic news literacy. It would be great to team up with them and see what is already working in order to better shape my curriculum. Additionally, I think I can improve on incorporating the idea that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience. Students encounter a slew of news and media every day in a variety of forms. I need to be better about trusting that they are also experts and allowing more flexibility in how I present the topic to them.

Overall, this has been one of my more successful units and I’m excited to improve it for future groups!