Tutorial: Text Classification

tutorial_basic_text_classification.RmdThis tutorial classifies movie reviews as positive or negative using the text of the review. This is an example of binary — or two-class — classification, an important and widely applicable kind of machine learning problem.

We’ll use the IMDB dataset that contains the text of 50,000 movie reviews from the Internet Movie Database. These are split into 25,000 reviews for training and 25,000 reviews for testing. The training and testing sets are balanced, meaning they contain an equal number of positive and negative reviews.

Let’s start and load Keras, as well as a few other required libraries.

Download the IMDB dataset

The IMDB dataset comes packaged with Keras. It has already been preprocessed such that the reviews (sequences of words) have been converted to sequences of integers, where each integer represents a specific word in a dictionary.

The following code downloads the IMDB dataset to your machine (or uses a cached copy if you’ve already downloaded it):

imdb <- dataset_imdb(num_words = 10000)

c(train_data, train_labels) %<-% imdb$train

c(test_data, test_labels) %<-% imdb$testThe argument num_words = 10000 keeps the top 10,000 most frequently occurring words in the training data. The rare words are discarded to keep the size of the data manageable.

Conveniently, the dataset comes with an index mapping words to integers, which has to be downloaded separately:

Explore the data

Let’s take a moment to understand the format of the data. The dataset comes preprocessed: each example is an array of integers representing the words of the movie review. Each label is an integer value of either 0 or 1, where 0 is a negative review, and 1 is a positive review.

[1] "Training entries: 25000, labels: 25000"The texts of the reviews have been converted to integers, where each integer represents a specific word in a dictionary. Here’s what the first review looks like:

[1] 1 14 22 16 43 530 973 1622 1385 65 458 4468 66 3941 4 173

[17] 36 256 5 25 100 43 838 112 50 670 2 9 35 480 284 5

[33] 150 4 172 112 167 2 336 385 39 4 172 4536 1111 17 546 38

[49] 13 447 4 192 50 16 6 147 2025 19 14 22 4 1920 4613 469

[65] 4 22 71 87 12 16 43 530 38 76 15 13 1247 4 22 17

[81] 515 17 12 16 626 18 2 5 62 386 12 8 316 8 106 5

[97] 4 2223 5244 16 480 66 3785 33 4 130 12 16 38 619 5 25

[113] 124 51 36 135 48 25 1415 33 6 22 12 215 28 77 52 5

[129] 14 407 16 82 2 8 4 107 117 5952 15 256 4 2 7 3766

[145] 5 723 36 71 43 530 476 26 400 317 46 7 4 2 1029 13

[161] 104 88 4 381 15 297 98 32 2071 56 26 141 6 194 7486 18

[177] 4 226 22 21 134 476 26 480 5 144 30 5535 18 51 36 28

[193] 224 92 25 104 4 226 65 16 38 1334 88 12 16 283 5 16

[209] 4472 113 103 32 15 16 5345 19 178 32Movie reviews may be different lengths. The below code shows the number of words in the first and second reviews. Since inputs to a neural network must be the same length, we’ll need to resolve this later.

[1] 218

[1] 189Convert the integers back to words

It may be useful to know how to convert integers back to text. We already have the word_index we downloaded above — a list with words as keys and integers as values. If we create a data frame from it, we can conveniently use it in both directions.

word_index_df <- data.frame(

word = names(word_index),

idx = unlist(word_index, use.names = FALSE),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

# The first indices are reserved

word_index_df <- word_index_df %>% mutate(idx = idx + 3)

word_index_df <- word_index_df %>%

add_row(word = "<PAD>", idx = 0)%>%

add_row(word = "<START>", idx = 1)%>%

add_row(word = "<UNK>", idx = 2)%>%

add_row(word = "<UNUSED>", idx = 3)

word_index_df <- word_index_df %>% arrange(idx)

decode_review <- function(text){

paste(map(text, function(number) word_index_df %>%

filter(idx == number) %>%

select(word) %>%

pull()),

collapse = " ")

}Now we can use the decode_review function to display the text for the first review:

[1] "<START> this film was just brilliant casting location scenery story direction

everyone's really suited the part they played and you could just imagine being there

robert <UNK> is an amazing actor and now the same being director <UNK> father came from

the same scottish island as myself so i loved the fact there was a real connection with

this film the witty remarks throughout the film were great it was just brilliant so much

that i bought the film as soon as it was released for <UNK> and would recommend it to

everyone to watch and the fly fishing was amazing really cried at the end it was so sad

and you know what they say if you cry at a film it must have been good and this

definitely was also <UNK> to the two little boy's that played the <UNK> of norman and

paul they were just brilliant children are often left out of the <UNK> list i think

because the stars that play them all grown up are such a big profile for the whole film

but these children are amazing and should be praised for what they have done don't you

think the whole story was so lovely because it was true and was someone's life after all

that was shared with us all"Prepare the data

The reviews — the arrays of integers — must be converted to tensors before fed into the neural network. This conversion can be done a couple of ways:

One-hot-encode the arrays to convert them into vectors of 0s and 1s. For example, the sequence [3, 5] would become a 10,000-dimensional vector that is all zeros except for indices 3 and 5, which are ones. Then, make this the first layer in our network — a

denselayer — that can handle floating point vector data. This approach is memory intensive, though, requiring anum_words * num_reviewssize matrix.Alternatively, we can pad the arrays so they all have the same length, then create an integer tensor of shape

num_examples * max_length. We can use an embedding layer capable of handling this shape as the first layer in our network.

In this tutorial, we will use the second approach.

Since the movie reviews must be the same length, we will use the pad_sequences function to standardize the lengths:

train_data <- pad_sequences(

train_data,

value = word_index_df %>% filter(word == "<PAD>") %>% select(idx) %>% pull(),

padding = "post",

maxlen = 256

)

test_data <- pad_sequences(

test_data,

value = word_index_df %>% filter(word == "<PAD>") %>% select(idx) %>% pull(),

padding = "post",

maxlen = 256

)Let’s look at the length of the examples now:

[1] 256

[1] 256And inspect the (now padded) first review:

[1] 1 14 22 16 43 530 973 1622 1385 65 458 4468 66 3941 4

[16] 173 36 256 5 25 100 43 838 112 50 670 2 9 35 480

[31] 284 5 150 4 172 112 167 2 336 385 39 4 172 4536 1111

[46] 17 546 38 13 447 4 192 50 16 6 147 2025 19 14 22

[61] 4 1920 4613 469 4 22 71 87 12 16 43 530 38 76 15

[76] 13 1247 4 22 17 515 17 12 16 626 18 2 5 62 386

[91] 12 8 316 8 106 5 4 2223 5244 16 480 66 3785 33 4

[106] 130 12 16 38 619 5 25 124 51 36 135 48 25 1415 33

[121] 6 22 12 215 28 77 52 5 14 407 16 82 2 8 4

[136] 107 117 5952 15 256 4 2 7 3766 5 723 36 71 43 530

[151] 476 26 400 317 46 7 4 2 1029 13 104 88 4 381 15

[166] 297 98 32 2071 56 26 141 6 194 7486 18 4 226 22 21

[181] 134 476 26 480 5 144 30 5535 18 51 36 28 224 92 25

[196] 104 4 226 65 16 38 1334 88 12 16 283 5 16 4472 113

[211] 103 32 15 16 5345 19 178 32 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

[226] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

[241] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

[256] 0Build the model

The neural network is created by stacking layers — this requires two main architectural decisions:

- How many layers to use in the model?

- How many hidden units to use for each layer?

In this example, the input data consists of an array of word-indices. The labels to predict are either 0 or 1. Let’s build a model for this problem:

# input shape is the vocabulary count used for the movie reviews (10,000 words)

vocab_size <- 10000

model <- keras_model_sequential()

model %>%

layer_embedding(input_dim = vocab_size, output_dim = 16) %>%

layer_global_average_pooling_1d() %>%

layer_dense(units = 16, activation = "relu") %>%

layer_dense(units = 1, activation = "sigmoid")

model %>% summary()____________________________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

====================================================================================

embedding_1 (Embedding) (None, None, 16) 160000

____________________________________________________________________________________

global_average_pooling1d_1 (GlobalAv (None, 16) 0

____________________________________________________________________________________

dense_3 (Dense) (None, 16) 272

____________________________________________________________________________________

dense_4 (Dense) (None, 1) 17

====================================================================================

Total params: 160,289

Trainable params: 160,289

Non-trainable params: 0

____________________________________________________________________________________The layers are stacked sequentially to build the classifier:

- The first layer is an

embeddinglayer. This layer takes the integer-encoded vocabulary and looks up the embedding vector for each word-index. These vectors are learned as the model trains. The vectors add a dimension to the output array. The resulting dimensions are: (batch, sequence, embedding). - Next, a

global_average_pooling_1dlayer returns a fixed-length output vector for each example by averaging over the sequence dimension. This allows the model to handle input of variable length, in the simplest way possible. - This fixed-length output vector is piped through a fully-connected (

dense) layer with 16 hidden units. - The last layer is densely connected with a single output node. Using the

sigmoidactivation function, this value is a float between 0 and 1, representing a probability, or confidence level.

Loss function and optimizer

A model needs a loss function and an optimizer for training. Since this is a binary classification problem and the model outputs a probability (a single-unit layer with a sigmoid activation), we’ll use the binary_crossentropy loss function.

This isn’t the only choice for a loss function, you could, for instance, choose mean_squared_error. But, generally, binary_crossentropy is better for dealing with probabilities — it measures the “distance” between probability distributions, or in our case, between the ground-truth distribution and the predictions.

Later, when we are exploring regression problems (say, to predict the price of a house), we will see how to use another loss function called mean squared error.

Now, configure the model to use an optimizer and a loss function:

Create a validation set

When training, we want to check the accuracy of the model on data it hasn’t seen before. Create a validation set by setting apart 10,000 examples from the original training data. (Why not use the testing set now? Our goal is to develop and tune our model using only the training data, then use the test data just once to evaluate our accuracy).

Train the model

Train the model for 20 epochs in mini-batches of 512 samples. This is 20 iterations over all samples in the x_train and y_train tensors. While training, monitor the model’s loss and accuracy on the 10,000 samples from the validation set:

history <- model %>% fit(

partial_x_train,

partial_y_train,

epochs = 40,

batch_size = 512,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val),

verbose=1

)Train on 15000 samples, validate on 10000 samples

Epoch 1/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 56us/step - loss: 0.6916 - acc: 0.6060 - val_loss: 0.6895 - val_acc: 0.5805

Epoch 2/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.6851 - acc: 0.7123 - val_loss: 0.6804 - val_acc: 0.7446

Epoch 3/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 32us/step - loss: 0.6713 - acc: 0.7484 - val_loss: 0.6625 - val_acc: 0.7322

Epoch 4/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 33us/step - loss: 0.6454 - acc: 0.7679 - val_loss: 0.6329 - val_acc: 0.7712

Epoch 5/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 42us/step - loss: 0.6068 - acc: 0.7939 - val_loss: 0.5929 - val_acc: 0.7876

Epoch 6/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.5597 - acc: 0.8133 - val_loss: 0.5490 - val_acc: 0.8033

Epoch 7/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.5087 - acc: 0.8345 - val_loss: 0.5020 - val_acc: 0.8210

Epoch 8/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 38us/step - loss: 0.4595 - acc: 0.8512 - val_loss: 0.4601 - val_acc: 0.8369

Epoch 9/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.4154 - acc: 0.8650 - val_loss: 0.4242 - val_acc: 0.8476

Epoch 10/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 38us/step - loss: 0.3780 - acc: 0.8770 - val_loss: 0.3956 - val_acc: 0.8535

Epoch 11/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.3467 - acc: 0.8862 - val_loss: 0.3725 - val_acc: 0.8612

Epoch 12/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.3209 - acc: 0.8931 - val_loss: 0.3542 - val_acc: 0.8673

Epoch 13/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 37us/step - loss: 0.2989 - acc: 0.8989 - val_loss: 0.3414 - val_acc: 0.8662

Epoch 14/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.2800 - acc: 0.9038 - val_loss: 0.3285 - val_acc: 0.8736

Epoch 15/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.2633 - acc: 0.9090 - val_loss: 0.3189 - val_acc: 0.8759

Epoch 16/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 41us/step - loss: 0.2485 - acc: 0.9148 - val_loss: 0.3119 - val_acc: 0.8778

Epoch 17/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 33us/step - loss: 0.2355 - acc: 0.9193 - val_loss: 0.3051 - val_acc: 0.8796

Epoch 18/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.2234 - acc: 0.9233 - val_loss: 0.3004 - val_acc: 0.8801

Epoch 19/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 39us/step - loss: 0.2124 - acc: 0.9266 - val_loss: 0.2965 - val_acc: 0.8812

Epoch 20/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 35us/step - loss: 0.2021 - acc: 0.9300 - val_loss: 0.2931 - val_acc: 0.8823

Epoch 21/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 35us/step - loss: 0.1927 - acc: 0.9347 - val_loss: 0.2904 - val_acc: 0.8830

Epoch 22/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 39us/step - loss: 0.1839 - acc: 0.9395 - val_loss: 0.2886 - val_acc: 0.8840

Epoch 23/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 33us/step - loss: 0.1761 - acc: 0.9426 - val_loss: 0.2873 - val_acc: 0.8841

Epoch 24/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 35us/step - loss: 0.1690 - acc: 0.9459 - val_loss: 0.2866 - val_acc: 0.8850

Epoch 25/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.1606 - acc: 0.9497 - val_loss: 0.2864 - val_acc: 0.8845

Epoch 26/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 35us/step - loss: 0.1540 - acc: 0.9519 - val_loss: 0.2871 - val_acc: 0.8839

Epoch 27/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 38us/step - loss: 0.1475 - acc: 0.9548 - val_loss: 0.2877 - val_acc: 0.8855

Epoch 28/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 39us/step - loss: 0.1412 - acc: 0.9570 - val_loss: 0.2878 - val_acc: 0.8855

Epoch 29/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.1354 - acc: 0.9597 - val_loss: 0.2891 - val_acc: 0.8857

Epoch 30/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 39us/step - loss: 0.1299 - acc: 0.9617 - val_loss: 0.2911 - val_acc: 0.8862

Epoch 31/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 33us/step - loss: 0.1250 - acc: 0.9632 - val_loss: 0.2920 - val_acc: 0.8863

Epoch 32/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.1197 - acc: 0.9653 - val_loss: 0.2939 - val_acc: 0.8868

Epoch 33/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 37us/step - loss: 0.1150 - acc: 0.9679 - val_loss: 0.2960 - val_acc: 0.8854

Epoch 34/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 33us/step - loss: 0.1101 - acc: 0.9697 - val_loss: 0.2989 - val_acc: 0.8847

Epoch 35/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 35us/step - loss: 0.1061 - acc: 0.9702 - val_loss: 0.3026 - val_acc: 0.8857

Epoch 36/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.1021 - acc: 0.9722 - val_loss: 0.3057 - val_acc: 0.8830

Epoch 37/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 0s 32us/step - loss: 0.0978 - acc: 0.9745 - val_loss: 0.3086 - val_acc: 0.8830

Epoch 38/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 37us/step - loss: 0.0939 - acc: 0.9762 - val_loss: 0.3110 - val_acc: 0.8825

Epoch 39/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 36us/step - loss: 0.0897 - acc: 0.9771 - val_loss: 0.3142 - val_acc: 0.8823

Epoch 40/40

15000/15000 [==============================] - 1s 34us/step - loss: 0.0861 - acc: 0.9786 - val_loss: 0.3181 - val_acc: 0.8818Evaluate the model

And let’s see how the model performs. Two values will be returned. Loss (a number which represents our error, lower values are better), and accuracy.

25000/25000 [==============================] - 0s 15us/step

$loss

[1] 0.34057

$acc

[1] 0.8696

This fairly naive approach achieves an accuracy of about 87%. With more advanced approaches, the model should get closer to 95%.

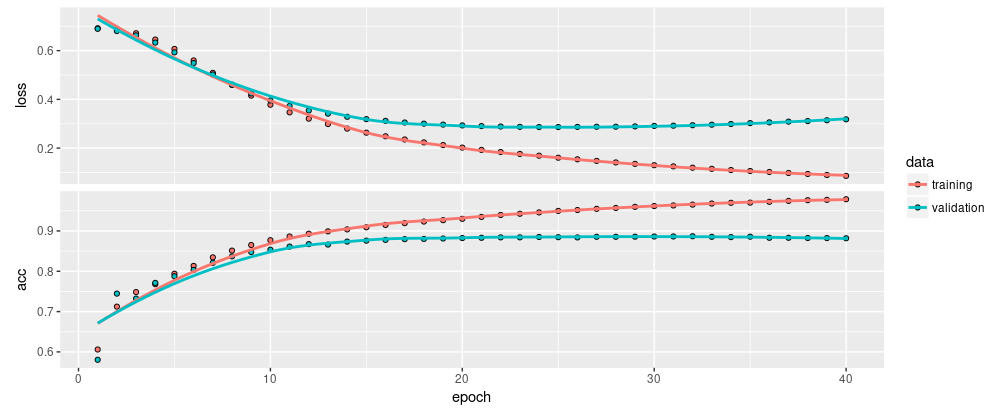

Create a graph of accuracy and loss over time

fit returns a keras_training_history object whose metrics slot contains loss and metrics values recorded during training. You can conveniently plot the loss and metrics curves like so:

The evolution of loss and metrics can also be seen during training in the RStudio Viewer pane.

Notice the training loss decreases with each epoch and the training accuracy increases with each epoch. This is expected when using gradient descent optimization — it should minimize the desired quantity on every iteration.

This isn’t the case for the validation loss and accuracy — they seem to peak after about twenty epochs. This is an example of overfitting: the model performs better on the training data than it does on data it has never seen before. After this point, the model over-optimizes and learns representations specific to the training data that do not generalize to test data.

For this particular case, we could prevent overfitting by simply stopping the training after twenty or so epochs. Later, you’ll see how to do this automatically with a callback.

More Tutorials

Check out these additional tutorials to learn more:

Basic Classification — In this tutorial, we train a neural network model to classify images of clothing, like sneakers and shirts.

Basic Regression — This tutorial builds a model to predict the median price of homes in a Boston suburb during the mid-1970s.

Overfitting and Underfitting — In this tutorial, we explore two common regularization techniques (weight regularization and dropout) and use them to improve our movie review classification results.

Save and Restore Models — This tutorial demonstrates various ways to save and share models (after as well as during training).